Nasdaq has no “opening bell.” Unlike the New York Stock Exchange, with its loud and chaotic trading floor, Nasdaq is entirely electronic, as befits the many high-tech companies whose shares are listed on it. But that hasn’t stopped Nasdaq from making the daily start of trading into a televised ritual, much like the ringing of the bell down on Wall Street.

Most mornings, representatives from a Nasdaq-traded company will come to a Times Square studio and ceremoniously push a button that purports to launch trading. And during holidays and significant events, Nasdaq often invites community groups and nonprofits to do the honors.

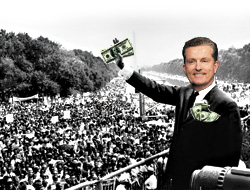

So it was that on the Friday before Martin Luther King Jr. Day this year, Roy Innis, chairman of the New York–based Congress of Racial Equality, stood before the cameras to push the magic button. Instrumental in organizing the Freedom Rides, and a sponsor of the 1963 March on Washington, CORE was a natural choice to open trading that day.

Not so intuitive was the man Innis brought along to stand at his right hand: Dennis Bassford, the blond, dimpled, 51-year-old co-founder and CEO of Moneytree, a Seattle-based company that’s been widely criticized for preying on minorities.

It was a huge P.R. coup for the Moneytree founder, a big win in his energetic campaign to spruce up his industry’s image—and his own. Often placed somewhere between tobacco companies and malt-liquor marketers in the ranks of most-loathed businesses, payday lending has long been accused of exploiting vulnerable people. But Bassford has carefully negotiated a new middle way for the business, expanding its reach while simultaneously investing in social service programs and reaching out to the very groups that are quick to blast him. In a press release last fall, Moneytree reported that its annual corporate giving is nearly $1 million. With the high-profile endorsement of a respected civil rights organization, it seems Bassford’s labors are paying off. The image of him standing alongside Innis was broadcast around the country and ran in The New York Times.

Explaining the choice later, a spokesperson for CORE lauded Bassford as “the kind of face for corporate America that corporate America needs.” He praised the company for its support of “financial literacy” programs, and for helping create a code of ethics for the payday lending industry.

Bassford’s efforts haven’t won over everyone, of course. Carl Mack, the former president of the Seattle NAACP branch, calls payday lending shops “piranhas in our community.” Far from advancing the cause of civil rights, he says, the industry has targeted minorities with its low-dollar loans, leading them quickly into high levels of debt with exorbitant fees.

King County Council member Larry Gossett agrees, saying that while Bassford is a “nice guy,” his business is a “usurious, parasitic entity” that takes advantage of people at the end of their rope. “I don’t know how anybody in good conscience could support the payday loan industry,” says Gossett, who is black. “The fact that you spend $150,000 a quarter helping nonprofits, that’s nice, but that doesn’t take away from the fact that overall, the industry is quite exploitative.”

For his part Bassford says he doesn’t see himself as either a hero or a villain in the ideological fight over payday lending, just someone offering up a credit option for people who might not otherwise be able to get it. “I believe that our customers totally understand this transaction,” he says. “I think we represent a choice among the many choices that people have—and clearly a better choice.”

Bassford graduated from Boise State—famous for its Smurf Turf blue football field—in 1980 with a degree in accounting. He became a certified public accountant, and worked in the field for two years before deciding it wasn’t for him and moving to Seattle. He had been in town for a couple of months when a friend planted the idea of going into the check-cashing business in his head.

In 1983, Bassford, along with his brother and sister-in-law, opened the first Moneytree in Renton, with the initial capital all coming from family. “It wasn’t a lot of money,” he recalls. “It was pretty much my mom and grandma and brother and sister and I put together what we had.” The primary business was cashing checks for a fee for people who didn’t have the requisite accounts or identification necessary to get cash at a bank, or who just needed a place to cash a check during off hours. The siblings acted as tellers, managers, and operators as they began expanding the business.

Twelve years later, payday lending was legalized in Washington state, and Bassford was quick to jump in. The move was a good one for him. He’s become the largest locally owned payday lender in the state, according to the Department of Financial Institutions (DFI) database, with 62 licensed locations. (Texas-based ACE Cash Express and Advance America, a publicly traded company based in South Carolina, both have roughly twice as many outlets in Washington.) Moneytree now extends across five Western states, with Washington still Bassford’s biggest market.

To promote Moneytree’s payday lending business in the mid-1990s, an actor donned a hokey caterpillar suit to declare the usefulness of the new loans in a pinched, nasal voice that was just obnoxious enough to be unforgettable. The caterpillar has since gone digital and has its own bobblehead doll.

The basic premise of a payday loan is simple: You walk in and provide the retailer with a postdated check for the amount of the loan you wish to get ($700 is the maximum in our state), plus interest. Fees are regulated by statute: up to 15 percent for the first $500 and up to 10 percent for the next $200. So borrowers wanting the maximum loan must write a check for $795. The retailer will deposit the check in about two weeks—presumably the next payday.

People with low incomes or bad credit tend to become payday loan customers. There are no credit checks at Moneytree. And that’s where the accusations of predatory lending begin.

Patricia Davis, a 47-year-old Greenwood resident, went through a divorce a little more than a decade ago. She says that while the dust was settling, her job at an ad agency wasn’t quite enough to cover her nearly doubled expenses one month, and her credit wasn’t good enough to get a credit card. So she walked down the street to a Moneytree for a $500 payday loan. “You think you only need it for two weeks. That one time ended up being a three-year cycle,” she says. “That three years cost me $3,600 in fees.”

Davis would have paid $75 to get the initial loan. But when that loan came due two weeks later, she found she still didn’t have enough money both to pay it back and meet her expenses, so she took out another loan, again paying $75. Under Washington law, customers can’t take out a loan to pay off the old one—called “rolling over” a loan—but they can use whatever cash they have on hand to pay off the old loan and then immediately take out a new one—which is effectively the same thing. By taking out a new loan once or twice a month to keep the last one paid off, Davis paid more than seven times the original cash advance.

Davis says that when she went in, the 391 percent annual interest rate allowed under state law was disclosed on loan documents, but she was assured that it didn’t apply to her since her loan was only short-term, not for a year. What she wasn’t planning on was being unable to put together the money to pay it back right away and still make ends meet. “It’s like an addiction,” she says.

Davis says it took her three years to save enough money, pay off the debt, and still have enough left over to end the cycle. She says her financial situation now is much more stable. She works with the Statewide Poverty Action Network, a Seattle-based nonprofit that fights for increased payday-lending regulation, including lower rates.

Julian Pena, 22, worked for a Moneytree branch in Tacoma for seven months in 2007. He says that while he didn’t have loan quotas to meet each month—so no incentives to try to sell people on loans they didn’t need or couldn’t afford—many customers would come to the stores for a new loan every two weeks, shelling out the high fees each time. “Some people come in to get payday loans for gambling money or drug money,” he adds. Regardless of what tellers suspect about the motives, Pena says, as long as proof of a job and a bank account number are provided, a loan is forthcoming.

The payday industry’s habit of locating in predominantly low-income neighborhoods, especially those with a high concentration of minorities or immigrants, has given it a bad reputation among consumer advocates. In November 2007, University of Washington sociology professor Alexes Harris overlaid payday lending locations with census data maps to show a concentration of lenders in the more ethnically diverse and lower-income pockets of the city. Harris and her colleague Barbara Reskin also interviewed 154 customers from locations throughout King County and found that borrowers were disproportionately people of color. The median income of all interviewees was $33,336.

But Harris says most of the interviewees seemed very cognizant of the risk they were taking in accepting the high-cost loans—they just couldn’t get the cash anywhere else. “People knew they were getting screwed, but they needed the money,” she says. (She adds that the study didn’t have a large enough sample to generalize the findings.)

James Kelly, president of the Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle, says many nonwhite, low-income residents are still regarded with suspicion by banks, which avoid locating branches in their neighborhoods. A search of Google Maps would seem to back him up: There are only three bank branches within a half-mile of Moneytree’s Rainier Avenue location, but there are 10 bank branches within the same distance of the Ballard Moneytree.

Kelly is a little leery of the industry, but, he says, “When people are drowning—and people are drowning—my issue is, throw them a rope.”

The cycle of debt and the high fees associated with payday lending inspired Jobs with Justice, a Washington coalition of unions and other labor groups, to name Bassford its Grinch of the Year in 2006. “We know that Moneytree believes they’re providing a community service,” says JWJ organizer Debbie Carlsen, whose group calls Bassford “Dennis the Menace.” “We believe that a 400 percent interest rate is not a community service.”

Bassford argues that Carlsen is wrong about the harm caused by payday loans. He points to a November 2007 study done by the New York Federal Reserve, which concluded that in Georgia and North Carolina, states where payday loans were banned, people were more likely to write bad checks to cover their expenses, paying bounced check fees in the process. A $29 fee on a $150 check amounts to an APR of 503 percent, according to the study, compared to the 391 percent APR allowed at Washington payday lenders. The study also found that people in states without payday lending were more likely to file for Chapter 7 bankruptcy.

More important than the question of price is whether borrowers go into default, says University of Washington finance professor Alan Hess. According to the Center for Responsible Lending—a nonprofit research and policy organization focused on what it deems abusive financial practices—the default rate on payday loans nationally is between 5 percent and 8 percent. Hess says that as long as people are eventually able to pay off their debts, even if it requires taking out additional payday loans over a period of time and exorbitant fees, “that sounds like good news.”

Even Davis acknowledges that without the payday loan, her only other options were to destroy her credit by bouncing checks or defaulting on her bills. The predatory nature of it, according to Davis, lay in the assurances from clerks selling the loan that she could expect it to be a short-term thing. For most people who take out one loan, there will be another. According to the DFI’s most recent payday lending report, of the 3.5 million payday loans made in the state, less than 3 percent were to onetime borrowers.

Whether payday lending helps or hurts, it has made Bassford a rich man. At the time of Bassford’s 2003 divorce from Susan Denise Bassford, a payday lending mogul in her own right in California, his Mercer Island home at the end of a gated, private drive overlooking Lake Washington was valued at $3.5 million. During his five-year marriage to Susan Bassford, who kept her name after they parted ways, two stepchildren joined his family. He has no children of his own, and Susan took the family dog, Snoopy, back to California.

Meanwhile, Bassford has been seeking to get in the good graces of advocacy groups that represent his business’ target customer. Last year, Moneytree ranked No. 20 on the Puget Sound Business Journal‘s list of most philanthropic Washington companies.

The Urban League is one of the local organizations to which Bassford has reached out. Kelly says that after Hurricane Katrina hit, the League was helping provide support to people who relocated here. Bassford made phone cards and about $500 in cash available to refugees.

Moneytree has also recently started to provide $5,000 in annual scholarship money to each of four undergrads at the UW School of Business. These “Moneytree scholars,” as they’re known, are trained to give lectures on personal-finance basics in local high schools. Michael Verchot, director of the university’s Business and Economic Development Center, runs the program and says he had no problem bringing Moneytree in as a partner. “They’re providing some access to credit that no other financial institution is providing,” he says. “It’s certainly better than bouncing checks and ruining your credit history.”

But not everyone is willing to receive the largesse. Roberto Maestas, director of El Centro de la Raza, says Moneytree approached him a few years ago and offered to provide much-needed financial help with a kitchen remodeling project at the headquarters. Ultimately the group decided against taking the cash because the question of whether or not payday lending is fundamentally predatory had not been resolved to El Centro’s satisfaction. “We said we were not in a position to accept donations from Moneytree,” Maestas says.

One of Bassford’s biggest charitable efforts has been in the state of Nevada—which, perhaps not surprisingly, is Moneytree’s largest market outside of Washington, with most of the outlets in Las Vegas. There, Bassford has pledged $100,000 over five years to support Nevada Partners, a nonprofit that trains low-income and minority residents for jobs in the hotel and casino industry. Bassford’s donation was earmarked for teaching “financial literacy” to program participants. Steven Horsford, an African American who is the head of Nevada Partners as well as a state senator, says he thoroughly researched Moneytree before accepting cash from the group and liked what he saw.

But the connection to CORE has provided the brightest halo for Bassford’s company to date.

Among civil rights groups, CORE, it would be fair to say, represents pretty low-hanging fruit for a business like Moneytree. Founder Roy Innis is a libertarian iconoclast, particularly on economic matters. He contributes to intellectualconservative.com, and on Feb. 5, he opined in the right-leaning Washington Times that the money being poured into alternative energy sources, rather than searching for fuel in places like the Arctic, is making it harder for people struggling to pay gas and energy costs now. In 2003, the Journal of Blacks in Higher Education detailed Innis’ ideological evolution, beginning with his endorsement of Richard Nixon in 1968. Over the next several years, he would come to the defense of the National Rifle Association, and support Ronald Reagan’s presidential bid. In 1988, he famously got in a shoving match with the Rev. Al Sharpton on a TV talk show. Last week he appeared as a guest speaker at a conference sponsored by the Heartland Institute debunking global warming.

The man who first brought Innis and Bassford together is Michael Shannon, Moneytree’s head of public affairs. Shannon was previously employed as a legislative aide in the office of Rep. Jim McDermott, where Shannon worked on the Africa Growth and Opportunity Act in the mid-1990s, which CORE supported. Thinking his boss might have some insight for CORE on how small loans, like payday lending, could be a part of CORE’s goals for improving financial education, Shannon introduced the two men. “[CORE is] an organization that’s very up on economic issues,” Shannon says. Innis’ son, Niger, says CORE was impressed that Bassford, as a member of a trade association, had been involved in creating a code of ethics for the payday lending industry. CORE began turning to him as a source of advice as it developed a financial literacy program.

Around the same time, Nevada Partners’ Horsford, who knows the Innis family, invited CORE to tour his facility in Vegas. Niger Innis says he was impressed with the operation, and when he learned that Bassford was providing financial support, it gave him further confidence that Bassford wasn’t a loan shark in guppy clothing but a man seriously interested in how access to small loans could be part of helping people get on their feet financially.

Based in large part on Bassford’s work in Vegas, CORE made him an honoree at its annual “Living the Dream” Martin Luther King Jr. Day dinner in New York in January, alongside Bishop T.D. Jakes, the founder of a nondenominational black megachurch in Dallas, and retired Lt. Gen. Ricardo Sanchez, the former U.S. commander in Iraq.

“It was extremely humbling to me to even be on that list,” Bassford says.

Bassford‘s biggest concern is not just his reputation among community leaders and activists. Regular stories regarding the dangers of payday lending, featuring accounts like Davis’, have prompted continual state and federal legislative proposals aimed at gutting the industry. Seventeen pieces of legislation were under consideration in Olympia this year. The most far-reaching called for a 36 percent APR cap on the loans. Rep. Sherry Appleton, D-Kitsap, has been leading the charge for tougher regulation, picking up support from the likes of House Speaker Frank Chopp. She says the issue came on her radar screen when people from the Bremerton Naval Yard complained about the impact the industry had on sailors. None of the legislation made it out of committee this year, but Appleton promises to be back next year.

Appleton’s proposed cap mimics a federal law enacted in 2006 that limits the APR on small loans made to active-duty military members to 36 percent, a number payday lenders say will drive them out of business. Bassford explains that a 36 percent cap would mean that he could charge about $1.38 per $100 on a short-term loan. For loans that aren’t paid back right away or get rolled over, that might eventually add up. But for the loans that are paid back at the next payday, it would eliminate his profit. As a result of the cap, “we don’t do business with the military,” he says. When a state enacts regulations that make the military cap a blanket requirement, he closes his stores completely. He pulled out of Oregon—the state where he was born—when a 36 percent rate cap took effect last year.

Bassford says the lower interest rate on such small loans doesn’t cover the basic expenses of his business, including labor, rent, and covering defaults. A 2005 study by a University of Florida professor and economist with the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation found that the average cost of making a payday loan was around $30. A 36 percent maximum APR would allow stores to charge at most $9.70 on a $700 loan.

Bassford believes the lack of payday lending to military families since the cap hasn’t eliminated the need for short-term credit for service members. Instead, he says, they are turning to more difficult-to-regulate online lenders. “When a rate cap like that goes through, the legal, the regulated responsible people like me, companies like Moneytree, will no longer provide this choice to consumers,” Bassford says. Lowering interest rates is “basically handing it over to unregulated Internet lenders from all over the world.”

But retired Air Force Col. Michael Hayden, spokesperson for the Military Officers Association of America, says that his and other military-centric organizations have begun creating their own short-term credit options for military members. Members of the Air Force, for example, can now apply for $500 interest-free loans through the Air Force Aid Society.

In addition to making regular trips to testify in Olympia and other states, Bassford generously greases the skids on both sides of the aisle for his legislative agenda. He has doled out more than $350,000 to local, state, and federal candidates over the past decade. That’s far more than Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz, who gave in the neighborhood of $135,000 during the same time period. State Sen. Margarita Prentice, a Democrat who backed the original 1995 legislation legalizing the industry, has received about $2,000 from Bassford in the past decade, for example. State law allows a maximum donation of $800 to legislative candidates per election cycle. But opponents aren’t left out, either. House Speaker Frank Chopp, a backer of the 36 percent cap, got a $700 check from Bassford in 2006. On the federal level, Bassford spreads his donations across party lines. Mitt Romney was his guy for president, but he declines to say why.

Bassford isn’t opposed to all regulation of his industry. In February, he traveled to Idaho to testify on behalf of a bill that would require payday lenders to give a list of names and contact information for all state-licensed credit counselors to customers before giving them a payday loan.

Some of Bassford’s larger competitors have chosen to spread the risk around, selling out to private equity firms or going public. Bassford says he’s kept the business in the family in part to avoid the pressures of stockholders who may ask him to cut things like employee benefits if times get lean. “What it really boils down to is, I don’t want to have a boss,” he says.

So while the politicians fight over whether his industry is a lifeline to those in need of a little extra help or a predator sinking its jaws into people at their most desperate hour, Bassford is enjoying the fruits of his philanthropic efforts, like pressing the Nasdaq button. You really hope that the day you ring in trading, the market goes up, he explains. On the day he did, honoring the country’s most revered civil rights leader, there was an initial surge, he says. “Then it came back down.”