James Sanderson had encountered a rare moment of industrial harmony.

It was the early 1990s, and the 750 men and women at Georgetown Steel were pumping out wire rods at peak performance. They had an abiding trust in management’s ability to run a smart company. That allegiance was rewarded with fat profit-sharing checks. In the basement-wage economy of Georgetown, South Carolina, Sanderson and his co-workers were blue-collar aristocracy.

“We were doing very good,” says Sanderson, president of Steelworkers Local 7898. “The plant was making money and we had good profit-sharing checks, and everything was going well.”

What he didn’t know was that it was about to end. Hundreds of miles to the north in Boston, a future presidential candidate was sizing up Georgetown’s books.

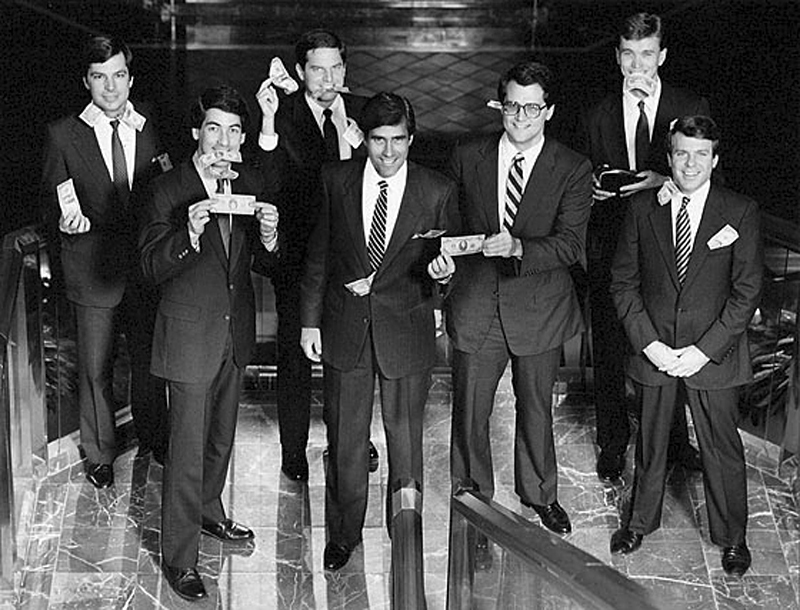

At the time, Mitt Romney had been running Bain Capital since 1984, minting a reputation as a prince of private investment. A future prospectus by Deutsche Bank would reveal that by the time he left in 1999, Bain had averaged a shimmering 88 percent annual return on investment. Romney would use that success to launch his political career.

His specialty was flipping companies—or what he often calls “creative destruction.” It’s the age-old theory that the new must constantly attack the old to bring efficiency to the economy, even if some are destroyed along the way. In other words, people like Romney are wolves, culling the herd of the weak and infirm.

His formula was simple: Bain would purchase a firm with little money down, then begin extracting huge management fees and paying Romney and his investors enormous dividends.

The result was that previously profitable companies were now burdened with debt. But much like the Enron boys, Romney’s battery of MBAs fancied themselves the smartest guys in the room. It didn’t matter if a company manufactured bicycles or contact lenses; they were certain they could run it better than anyone else.

Bain would slash costs, jettison workers, reposition product lines, and merge its new companies with other firms. With luck, they’d be able to dump the firm in a few years for millions more than they’d paid for it.

But the beauty of Romney’s thesis was that it really didn’t matter if the company succeeded. Since he was yanking out cash early and often, he would profit even if his targets collapsed.

Which was precisely the fate awaiting Georgetown Steel.

When Bain purchased the mill, Sanderson says, change was immediate. Equipment upgrades stopped. Maintenance became an afterthought. Managers were replaced by people who knew nothing of steel. The union’s profit-sharing plan was sliced twice in the first year—then whacked altogether.

“When Bain Capital took over, it seemed like everything was being neglected in our plant,” says Sanderson. “Nothing was being invested in our plant. We didn’t have the necessary time to maintain our equipment. They had people here that didn’t know what they were doing. It was like they were taking money from us and putting it somewhere else.”

History would prove him correct. While Georgetown was beginning its descent to bankruptcy, Romney was helping himself to the company’s treasury.

He should have known better. The year before Romney purchased Georgetown, he mounted his career in politics, setting his sights on the biggest target in Massachusetts: the U.S. Senate seat held by Ted Kennedy.

There were early signs that he might topple the Kennedy dynasty. Much like today, Romney was pitching himself as a commander of the economy, a man with the mastery to create jobs. Yet he suffered an affliction common to those atop the financial food chain: He assumed that what was good for him was good for all. Call it trickle-down blindness.

In the midst of that 1994 campaign, one of Romney’s companies, American Pad & Paper, bought a plant in Marion, Indiana. At the time, it was prosperous enough to be running three shifts.

Bain’s first move was to fire all 258 workers, then invite them to reapply for their jobs at lower wages and a 50 percent cut in health-care benefits.

“They came in and said, ‘You’re all fired,’ ” employee Randy Johnson told the Los Angeles Times. “‘If you want to work for us, here’s an application.’ We had insurance until the end of the week. That was it. It was brutal.”

But instead of reapplying, the workers went on strike. They also decided the good people of Massachusetts should know what kind of man wanted to be their senator. Suddenly, Indiana accents were showing up in Kennedy TV ads, offering tales of Romney’s villainy. He was sketched as a corporate Lucifer, one who wouldn’t blink at crushing little people if it meant prettifying his portfolio.

Needless to say, this wasn’t a proper leading-man’s role for a labor state like Massachusetts. Romney was pounded in the election, taking just 41 percent of the vote. Meanwhile, the Marion plant closed just six months after Bain’s purchase. The jobs were shipped to Mexico.

Yet Romney didn’t learn his lesson. He seemed incapable of noticing that his brand of “creative destruction” left a lot of human wreckage in its wake. Or that voters might see him as more scumbag than saint.

Just a few months after being hammered by Kennedy, he set fire to another company.

The move was classic Bain. Before buying Georgetown, Romney had purchased the Armco steel mill in Kansas City, Missouri, which had been in business more than 100 years. “We were setting a lot of records for production at that time,” says employee Steve Morrow. “We were making a lot of money, because we were getting profit-sharing.”

Bain combined Armco with the mill in Georgetown and foundries in Tempe, Arizona, and Duluth, Minnesota, to form the newly christened GS Industries.

Romney purchased Armco with just $8 million down, borrowing the rest of the $75 million price tag. Then he issued bonds—basically IOUs—to borrow even more to pay himself and his investors $36 million. Within a year, he’d already made four times his initial investment while barely lifting a finger. But he’d also run up a staggering $378 million in debt on GSI’s tab.

Steel is an infamously cyclical business, a worldwide commodity prone to the same wild price fluctuations as oil. The Kansas City plant forged parts for equipment used in mining gold and copper, leaving it susceptible to the instability of those markets as well. Yet the smartest guys in the room thought they could run the plant better than the people setting production records.

“They were getting rid of old managers and hiring new managers that didn’t have any steel experience,” says Morrow. “Some of the guys were nice guys and everything, but they didn’t have a clue what was going on.”

Many of the new supervisors were ex- military, people who believed that grown men and women are best motivated by punishment. Before Bain, says Morrow, “everybody got along.” Afterward? “They wanted to run the plant like a disciplinary environment. They wanted to discipline people for getting hurt on the job. They wanted to put us in an environment like a war, where we were always fighting with them.”

Romney was charging GSI $900,000 a year in management fees to run the company. The Kansas City mill received $900,000 worth of ineptitude in return.

Although Bain borrowed $97 million to retool the plant so it could also produce wire rods, it left the rest of the facility to rot. To save costs, Bain went miserly on everything from maintenance to spare parts and earplugs. Equipment deteriorated. Since the new managers didn’t know how to repair it, “they’d want to rent a new piece of equipment out instead of maintaining what we had,” says Morrow. The waste and inefficiency was breathtaking.

Bain’s plan all along was to streamline the company into greater profitability, then reap the rewards with a public stock offering. But the exact opposite was happening. Even Roger Regelbrugge, whom Bain installed as CEO, knew the debt was crushing GSI from within, according to Reuters. If a public offering didn’t materialize, the company would collapse.

Steel was about to enter a periodic downturn. Countries around the world were locked in a war of tariffs and government-subsidized production, creating a glut and driving down prices. Romney’s strategy of the flip was never meant to endure difficult times.

Workers saw the end coming; they were particularly worried that Bain was badly underfunding their pension plan. So they went on strike in 1997, bringing a traditional Rust Belt flair to the festivities by littering the streets with nails and gunning bottle rockets at security guards. When it was all over, the Steelworkers’ union agreed to wage and vacation cuts in exchange for extra health and pension safeguards should the plant close.

Yet GSI was now hemorrhaging money, says David Foster, the union official who negotiated the deal. He claims that Bain cursed the company by placing its own interests above those of customers or long-term stability. “Like a lot of private equity firms, Bain managed the company for financial results, not production results,” says Foster. “It didn’t invest in maintenance or immediate customer needs. All that came second to meeting monthly financial goals.”

It would take a few more years of bleeding, but GSI eventually fell to bankruptcy. The Kansas City mill closed for good; 750 people lost their jobs. Worse, Romney had shorted their pension fund by $44 million. The feds were forced to cover the difference, while workers saw their benefits slashed in bankruptcy court.

The battered Georgetown plant and the foundries in Arizona and Minnesota ultimately were bought out of bankruptcy by new companies. Their workforces were halved. Still, Romney walked away unbruised. All that debt was technically GSI’s, not Bain’s. Because he’d repaid himself and his investors just months after the purchase, Romney pocketed millions for running the company into the ground.

“They were clever and ruthless enough to pay their own investors back at a really high return rate,” says Foster.

This was the beauty of Romney’s racket. Even if he killed a company—and he tended to kill them fairly often—he still made out, leaving others to take the hit.

On the campaign trail, Romney describes his work at Bain as resurrecting distressed companies. In this version, he’s the white knight lifting troubled firms from the precipice of failure.

Not true.

Private equity companies like Bain rarely buy anything but profitable firms for one very compelling reason: The patient must be healthy enough to be force-fed all that debt. So it’s something of a misnomer for Republican opponents to slur him as a “vulture capitalist.”

“Romney is not a vulture capitalist, as Rick Perry says, since vultures eat dead carcasses,” notes Josh Kosman, who’s written about the private equity business for 15 years. He’s “more of a parasitic capitalist, since he destroys profitable businesses.”

Judging by the title of his book—The Buyout of America: How Private Equity Is Destroying Jobs and Killing the American Economy—it’s safe to assume that Kosman’s no fan of the industry. But he concedes that the business isn’t inherently wicked.

The game works like this: Big-money investors write checks to people like Romney, who pool that money to buy or invest in other companies. Internal company documents show that a year before Romney left Bain in 1999, one of his funds had reached a massive $10 billion.

Though Bain requires a $1 million minimum for a seat at the table, its investors don’t come only from the wealthiest 1 percent. They also include college endowments and teachers’ pension funds.

Jon Burgstone, a professor at the University of California-Berkeley’s Center for Entrepreneurship & Technology, sees private equity as essential to the economy. He may be a member of President Obama’s National Finance Committee, but he’s still an admirer of Bain. “Generally, private equity companies invest in larger firms that need reorganization, or in smaller companies that need growth capital,” he says. And their management can usually benefit from “very bright Bain consultants.”

That feeling is shared by Steven Kaplan, among the foremost scholars in the field. The University of Chicago finance professor says that, statistically speaking, firms like Bain improve a company’s cash flow while providing investors with a better return than the stock market.

There’s no question that Romney had a gift for minting money. In 1986, he bought medical-equipment manufacturer Calumet Coach for just $1 million, later flipping it for $34 million. He made 16 times his initial investment in the Gartner Group, a technology research firm. And in what was perhaps his crowning achievement, he bought a money-losing Wesley Jessen VisionCare for $6 million in 1994. Seven years later, it was sold for a dazzling $300 million.

Kaplan argues that critics rarely mention these success stories, preferring to “cherry-pick” deals that paint Romney as unmerciful and gluttonous. “I think it’s quite unfair,” he says. “He was extremely successful at Bain generating returns for his investors. Bain Capital had a tremendous track record. When you invest in dozens of companies, some of those deals don’t work out.”

But if critics are quick to disregard Romney’s triumphs, defenders are equally swift to rationalize his catastrophes. They’ll note that for all Romney’s bankruptcies, most were rescued by new companies and survive today. It’s the final dollar tally that matters. Yet they seem strangely incurious about the ruin he’s delivered across the country.

Take Kansas City, for example. The Armco plant closing involved more than the torching of 750 jobs, says Morrow. Contractors and suppliers collapsed. Workers’ children and widows lost health care and pension benefits. And while Bain received millions in tax breaks—paid for by the very people left holding the bag—Romney walked away millions richer.

So one might forgive everyday Americans for feeling they’re on the wrong end of a rigged game, one in which the wealthy always win—no matter how inept—and the little guy is left to hack through the debris.

Bain is a private company, meaning it has no obligation to reveal its practices. It’s never made public a list of companies it’s purchased. (Nor would Bain or the Romney campaign comment for this story.)

So in January, The Wall Street Journal did its best to piece together Romney’s track record, reviewing 77 investments made under his direction. It turned out that nearly one in three of the companies experienced severe financial trouble. One in five wound up in bankruptcy.

The more telling figure: Of Romney’s 10 biggest moneymakers, he ultimately destroyed four of them, leaving bankruptcy judges to clean up the mess.

As Foster sees it, Romney was an early pioneer of gaming the system. It would take another decade before large banks used many of the same principles to detonate the mortgage industry.

“The great irony is that his entire management experience at Bain Capital is buying companies and loading them up with debt and then looting the balance sheet,” Foster says. “It’s the very model that drove the American economy off the cliff, then left other people to manage the wreckage.”

Renee Fry doesn’t recognize the tin man she sees on TV, the candidate so congenitally wooden that he makes Al Gore seem like Flavor Flav. She was Romney’s deputy chief of staff when he was governor of Massachusetts. The guy she served was warm and considerate, quick to distill data and seize the big picture.

“I’m lucky because I know him from the day-to-day Mitt,” Fry says. “He liked going out and talking to people and learning from people. The Mitt I know had a real appreciation for people.”

But if Romney played the friendly politician, kindness wasn’t his specialty at Bain. He was generous to ranking executives, rewarding CEOs with huge bonuses. Yet he tended to treat those below his pay grade as little more than machinery.

Romney has repeatedly claimed to have created 100,000 jobs at Bain, and says that providing work for Americans was a primary company goal. He makes his case by citing Domino’s, Sports Authority, and Staples, companies that added jobs after Bain bought in. But Bain bought Domino’s just months before Romney left to run the Salt Lake City Olympics, meaning someone else created those jobs. And he didn’t manage Staples or Sports Authority; Bain was a minority investor in both.

By Romney’s logic, any large investor—say, the Texas teachers’ pension fund—also creates hundreds of thousands of jobs. The boast is so foolish that his campaign has since backed away from it.

Even Kaplan admits that private equity firms rarely create jobs. Workers are seen as costs, and costs are the enemy. According to Kosman, Romney was in truth among the most heinous job-killers of them all.

While writing his book, Kosman conducted an interview with a Bain managing partner. The man told him that when Bain was about to buy a company, its partners would hold a meeting. “He said that about half the time [they] would talk about cutting workers,” says Kosman. “They would never talk about adding workers. He said that job growth was never part of the plan.”

That claim was buttressed by the Associated Press, which studied 45 companies bought by Bain during Romney’s first decade. It found that 4,000 workers lost their jobs. The real figure is likely thousands higher, since the analysis didn’t account for bankruptcies or factory or store closings.

An example of Romney’s cold-blooded approach is his 1994 purchase of Dade International, an Illinois medical-equipment company. He soon merged it with two similar firms, a move that tripled sales. Once again, he couldn’t help but raid the vault, peeling away $100 million for himself and investors at the same time Dade was laying off 1,700 American workers.

After Bain closed a Dade plant in Puerto Rico, human resources manager Cindy Hewitt was asked to lure a dozen of those employees to work in the company’s Miami factory. But that plant soon closed as well. Though Romney was gobbling up millions, Bain still wanted those laid-off employees to repay their moving costs. “They were treated horribly,” Hewitt told The New York Times. “There was absolutely no concern for the employees. It was truly and completely profit-focused.”

Yet Bain’s molestation wasn’t complete. It was trying to sell Dade, but didn’t like the offers it received on the open market. So it created an artificial market of its own. In 1999 it forced Dade to borrow $242 million, which was used to buy back company stock from Bain, Dade executives, and their banker, Goldman Sachs.

Bain was again extracting profits with borrowed money. It had pushed Dade’s debt to a bracing $2 billion. To help pay for the deal, the company laid off another 367 workers. But that debt proved too much for Dade’s shoulders to carry. Three years later, the company was bankrupt.

Kosman calls it standard Romney operating procedure. To pump short-term earnings, he would essentially “starve a company,” whacking not just employees, but customer service and research-and-development funding—the very ingredients of long-term prosperity.

“I think they’re one of the worst, at least during Romney’s time,” Kosman says. “They were very aggressive about dividends. They were very aggressive about borrowing the most money they could. He’s very driven to be the best he could be, and that was to be as cutthroat as he could be. But in the process, he hurt a lot of companies and cost a lot of jobs, maybe tens of thousands of jobs.”

Kosman says it’s telling that Romney never cites companies he actually managed as evidence of his job-building skills.

“If Romney had some stories to tell, he’d use those stories,” he says. “I think it’s very interesting that he’s not telling those stories, because I think they don’t exist.”

Romney’s economic views were on stark parade during this year’s Michigan primary. He ripped President Obama for bailing out the auto industry, arguing that it should have been dealt with in his favorite resting place: bankruptcy court. He was particularly incensed that the president rescued workers’ pension funds before covering Wall Street’s bad loans.

But his faith in the free market wobbles when his friends need rescuing. Romney just as vigorously defends the $10 billion government bailout of Goldman Sachs, his investment partner at Bain.

After all, Romney frequently assumed the role of welfare queen himself. In 1988, he bought South Carolina photo-album maker Holson Burnes. In exchange for the firm’s promise to build a new factory, the people of Gaffney, South Carolina, gave Bain $5 million in bonds and $200,000 in utility upgrades. The plant closed just four years later. The 100 jobs there were later shipped to Mexico.

At GSI, he dumped $44 million in pension shortfalls on the federal government. And when he bought mattress-maker Sealy in 1997, he took $600,000 in welfare to move the firm from Ohio to North Carolina.

Even a company Romney cites as one of his greatest achievements—Steel Dynamics, where he was a minority investor—was practically launched by corporate welfare. Indiana taxpayers gave the firm $77 million to open a plant. Residents of DeKalb County actually had their income taxes raised solely to help Romney and his friends.

Tad DeHaven calls it “theft and redistribution.” He’s no yammering Trotskyite; DeHaven is a former budget advisor to Republican U.S. senators Jeff Sessions of Alabama and Tom Coburn of Oklahoma. Yet he notes that firms like Bain often get governments to subsidize their raiding parties.

The feds take $100 billion a year from everyday taxpayers and send it straight to companies like Romney’s, says DeHaven, who now works for the Cato Institute, a conservative think tank.

But like most good Republicans, he’s reticent to single out the candidate for criticism. “It depends on what he knew and Bain’s involvement in obtaining subsidies,” DeHaven says. “I don’t know if it makes him a hypocrite or not, but he should answer questions about it.”

Those answers won’t be forthcoming. Romney refuses to discuss most of the companies he purchased at Bain, nor will he release his tax records from those years. As a result, voters are left to make their own call on his catalogue of creative destruction—and what he might be like as president.

Romney has professed his admiration for Ronald Reagan. But judging by his business history, the president he most resembles is Vladimir Putin. Romney has devoted his life to ensuring that every last penny rises to a few hands at the top. And like Putin, he’s never shown much concern for the countrymen he tramples along the way.

“The word ‘oligarchy’ comes to mind,” says Michael Keating, when asked to envision a Romney presidency. Keating is a former business consultant and executive at Bertelsmann, a multinational investment firm that operates in 63 countries. He asserts that men like Romney “hide their antisocial actions behind a rhetoric of free-market capitalist platitudes. But in the end, it’s all about the bottom line—and only their own bottom line.

“I don’t think Romney is so much dangerous as he is unimaginative,” Keating adds. “And in the world we live in, that amounts to the same thing.”