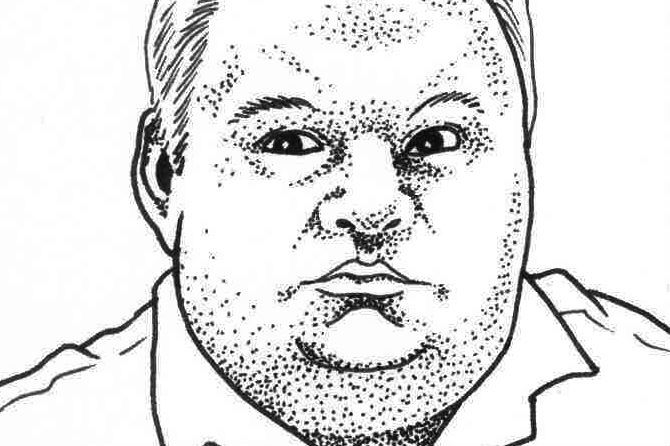

Long before Donald Trump secured the Republican nomination for president, Mike Daisey was shaping a new monologue about the man. He seemed the perfect subject for one of Daisey’s theatrical pieces, which took off in Seattle in the early aughts when he parlayed a job at Amazon into the breakout monologue 21 Dog Years. He has since grappled with mythic weirdos, including L. Ron Hubbard, Nicola Tesla, Steve Jobs (infamously), and now Trump.

Like so many others, Daisey didn’t believe the real-estate developer’s racist, sexist, and xenophobic campaign would last, but thought his monologue might get a short regional run out of it. He was wrong on both counts. As Trump’s campaign has soldiered on, spewing untruths and vitriol, The Trump Card has followed in its wake, selling out shows coast to coast. We talked to Daisey, who now lives in New York, in advance of his one-night-only engagement at the Neptune on Thursday, Sept. 22.

When did your work first get political? I would argue that the first piece that was mostly political was 21 Dog Years, in terms of its concerns about labor and what it means to work and the role of corporations in our lives; that’s when I feel my work really started to turn more toward the political. It started very early; that was my third monologue.

Now all of your monologues, even those not overtly so, delve into politics. Why is it important for you to engage in politics from the stage? I actually think that any theater artist that has nothing political in their work to me is synonymous with saying, “I make bad work.” It is not in vogue right now in the theater. There is a strong impulse to create work that is not political, that I would argue is aggressively apolitical where it sort of strives to not take a point of view, to portray different sides of an issue and then leave things sort of hanging and say, well, “The light falls on a complicated scene.” My problem with that is that I think it’s a kind of intellectual cowardice; I also think that it’s fundamentally bad drama because it’s telling us something that we already know. There is no person so naive that they need the theater to tell them that the world is complex.

But it seems that we all know quite a bit about Donald Trump. What are you telling us that is new here? You’re right. When you’re talking about Trump, you are talking about a topic that actually in terms of data, everybody has all the data they need. And from the outside, a show like this can give rise to this question of “Aren’t you preaching to the choir?” This presupposes that my show about Donald Trump is to tell people how bad Donald Trump is. I feel I would be very bad at my job if I actually thought that was a connection that needed to be made for people. This show assumes that audience is expecting me to rip Donald Trump apart, but instead I reverse the lens and talk about why they have come, why they, who know so much about him already, have chosen to come hear a show about Donald Trump. Actual art, actual political theater, says to the audience, “You already knew these facts, didn’t you? We’ll remind you of some of them but you already know them. What matters is how are you going to live with them.”

Why do you think a monologue is the most effective way of deliver that message? Theater is often very effective when you are put into a context where it is creating empathy through connectivity; where it can create webs of connections. People may have known all the facts, but an empathic human connection is missing. The underlying story of why do a monologue is about trying to create empathic connections.

Do you know if any Trump supporters have seen the show? Yeah. There was a guy after the show in Massachusetts and he stayed till the end and he was like, “Well, I hear what you are saying about Trump, but I don’t know why you aren’t talking more about Hillary,” and then he talked about how terrible Hillary is for 10 minutes. The show actually talks about Hillary as well, but this person obviously wishes the show was called, like, The Hillary Card. This kind of response is actually a sign of how theater works; because we are all present, because we feel like we have a voice; because the audience can talk to the person who made the theater, they feel present. It’s good that the production values aren’t so high and you don’t feel so distant from it that you can’t imagine it being about anything else. But that doesn’t change whether I am responsible for making a show that matches up with what each individual person wants to hear.

mbaumgarten@seattleweekly.com

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.