In the beginning, there were two congregations. The Westminster Church resided in a historic building in the heart of Capitol Hill, but its dwindling membership cast uncertainty over the congregation’s future. Church at the Center, on the other hand, was alive and well—although informal—with a growing congregation that worshipped in a Queen Anne movie theater where armchairs with cup holders stood in for padded pews. The pastors of these two churches saw a proverbial light in the merging of their visions. There was hope for the future, and there was a mission to serve the surrounding community.

On Easter Sunday 2006, attendees from the two former churches gathered for worship at the old Westminster building, thereby planting the seeds that would become Capitol Hill Presbyterian. In 2008, the church officially chartered as a congregation. It was an origin story fit for a Bible verse.

The palatial brick building has stood at the corner of Harvard Avenue and Howell Street for nearly 100 years, around the time when the neighborhood began to be considered an arts hub. A dark hall leading to the sanctuary pays tribute to the area’s rich artistic history, its walls lined with posters that advertise plays the congregation put on throughout the years. Cascading light from the church’s daycare room streams onto a poster for A Christmas Story that features dancing figures clad in colorful Victorian garb. Inside the sanctuary, stained-glass windows overlook two dozen pews upholstered in mottled brown fabric. A large wooden cross in the center of the stage is flanked by a Baldwin piano, a red drum kit to its left. Outside of the hours of worship, the large vacant building rests in a state of wonder tinged with gloom.

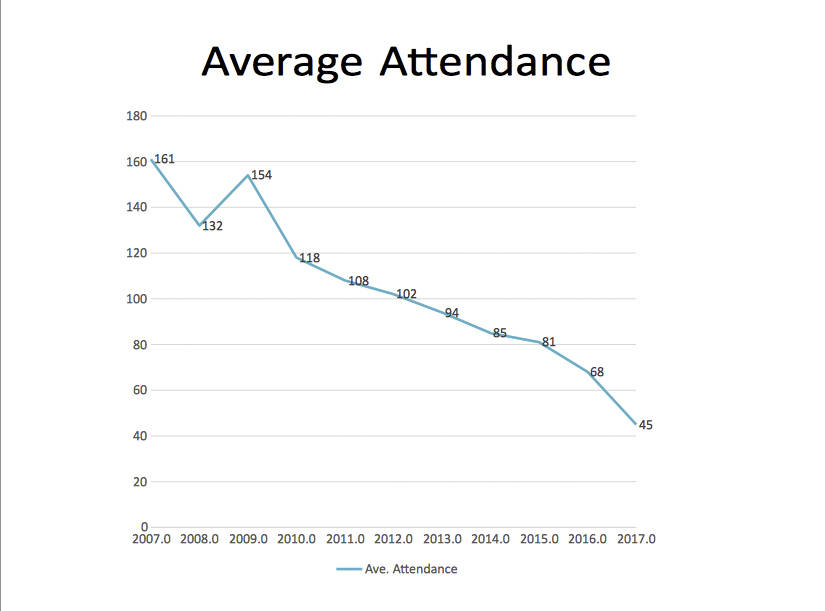

After a decade of Sunday services and daily recovery groups, the promise of the new congregation has reached a standstill. Dwindling church attendance—161 to 45 members from 2007 to 2017—and an inability to shoulder the costs of seismic retrofitting led the church board to recently announce that the congregation’s final service would be held on June 24 at 9:45 a.m.

Some members of the local Presbyterian community say that the congregation’s closure is due to a lack of engagement with the surrounding neighborhood and its resistance to take a stand on LGBTQ rights.

“If there’s one thing that is true for all our faith communities, it’s that the real work of ‘being church’ lies in the communities that we are placed in. This idea of maintaining an insular group that convenes on Sunday morning to worship God and then disperses without engagement with their neighbors or authentic concern for the issues in the community just isn’t viable,” Eliana Maxim, associate executive Presbyter at the Seattle Presbytery—which oversees 45 Presbyterian Churches in the region—wrote in an email to Seattle Weekly. “The days of attracting members to a church simply because of denominational loyalty or an enticing array of intergenerational programs are over. In some ways, we have returned to the early church where affiliation to a faith community was based on the relationships nurtured and invested for the long haul. Church is the practice, the action, of our professed faith.”

Meanwhile, local religious analysts say that the church’s closure signifies an identity crisis facing many traditional churches that have not adapted to the times. From 2012 to 2016, the Seattle Presbytery closed five churches, and its total membership went from 16,958 to 13,302.

“Our demographics as a mainline denomination is that we’re … usually older than the communities we’re in,” said Seattle Presbytery Executive Presbyter Scott Lumsden. “I think theologically, Capitol Hill is a bit more progressive than I think the congregation was.” Changing the dynamic of a church takes time, financial resources, and consistent leadership, which can be difficult to achieve as more and more congregants leave. However, Lumsden referenced success stories like Union Church in South Lake Union, which aside from its Sunday services, boasts a non-traditional approach to ministry through a coffee shop and venue.

Jeff Keuss, a professor of Christian Ministry, Theology and Culture at Seattle Pacific University, is also the executive director of Pivot NW, where he studies religious faith in 23– to 29-year-olds in the Pacific Northwest. Keuss’s research shows that twentysomethings are the region’s largest age demographic, and also the smallest population of churchgoers. The data he has collected reveals a “misalignment with churches’ sense of what is needed and what individuals are seeking,” Keuss wrote in an email to Seattle Weekly. Respondents to his surveys said they were searching for communities that allowed them to explore pressing questions significant to them; a place to be anonymous until they felt more comfortable opening up; a multigenerational space that breeds mentorship; and somewhere that they could witness people “live out what they believe.” Churches did not make the top of the list for meeting young people’s priorities, not because they were disenchanted by organized religion, but because they found community in yoga, book clubs, hiking groups, and organized sports.

This puts Seattle churches in an interesting predicament, since a 2015 Property Shark study ranked Seattle as having the second-highest number of places of worship per capita in the nation, trailing only Indianapolis. However, Seattle also placed second behind Portland in the number of residents who are religiously unaffiliated, at 33 percent. “We are essentially a place that is saturated with churches to attend, but people who don’t want to attend,” Keuss wrote, owing it to “a large push from denominations to send church planters our way as the great frontier of the ‘unaffiliated.’ ”

The Pacific Northwest’s abundant outdoor culture draws many former churchgoers to the mountains on the weekends, and recreational sports teams also tend to hold practices on Sunday mornings, notes James Wellman, professor and chair of the Comparative Religion Program at the University of Washington. When he originally looked at the issue in 2000, Wellman found that transplants’ “affiliations dropped out of the plane” as they flew over the Cascades to settle in Seattle. He’s currently conducting a new study to determine if there’s been an actual decline in membership in recent years. “I think often people mistake lower affiliation generally with decline, and certainly some churches are declining pretty dramatically, and that is the Mainline Protestant Churches, but that’s true throughout the country.”

In fact, the Pew Research Center’s 2014 U.S. Religious Landscape Study shows that the nation is becoming less Christian in general. Although the U.S. is still home to more Christians than any other nation, the percentage of Christians decreased from 78.4 to 70.6 percent between 2007 to 2014. Meanwhile, Americans who identify with non-Christian religions increased from 4.7 percent in 2007 to nearly 6 percent in 2014.

The reasons for the Capitol Hill Presbyterian closure are less straightforward. Karla Kuepker, a South Seattle resident who has commuted to the church for Sunday services since its inception, started to see a shift in membership around 2015 when the Supreme Court ruled same-sex marriage legal throughout the nation. Members who vehemently supported or opposed the ruling felt betrayed by the church board’s reticence to take a definitive position on the matter. “To be able to respect each other and love each other and still have civil discourse about this stuff is what we were aiming for,” Kuepker said. Yet that wasn’t enough for some of the congregants. “They wanted … our church to come down hard on one side or the other.” As an equal marriage supporter, she asked herself if she would be comfortable inviting an LGBTQ friend to the church, “and I had to be honest with myself and say no. And that’s where I think things broke down, I really do.”

She noticed that familiar faces slowly began disappearing from the pews on Sunday mornings. She kept holding out hope for her congregation until she received an email this past February informing her that the church would be closing. Despite signs of the church’s growing pains, Kuepker was crushed by the news. She’d relied on the congregation as her faith group since before Capitol Hill Presbyterian was created, back when Church at the Center still met in a movie theater. Kuepker was drawn to the church’s focus on the arts, the bands that would play modern music during worship, and the sermons that were adapted to the current day. “Let’s face it, the Bible is an old document,” Kuepker said. “I don’t get the analogy of the shepherd, because I’ve never seen a sheep alive in my life. So how is that relevant to me?” Instead, the Capitol Hill Presbyterian pastors shared their own experiences in modern terms that resonated with Kuepker.

Kuepker considered the congregation her family. But she’s unsure how often she’ll have reunions since many of the attendees were commuters who would drive from as far north as Everett.

Yet, Kuepker and others have not left the congregation and are committed to stay until the end. When Reverend Vonna Thomas began leading the church in January, she knew that the writing was already on the wall. The congregation tried to gain more members through the recovery groups that met in the church, but they still struggled to connect with the local community. “It speaks to the need to have a good fit in the neighborhood,” Thomas said as she sat in a first row pew last Friday. “My opinion is that you can have small congregations that are still incredibly vibrant. They’ve got to be outward focused, they can’t just be inward focused, so you’ve got to build those connections and have a good fit in your community.”

The church will stay within the ownership of the Presbytery after the final services, and will work with groups interested in acquiring the property. Kuepker and her family will take some time to grieve and recuperate after the church closes, but then she sees a new beginning in her journey at a Lutheran church in her neighborhood. As a former social worker, she’s attracted to their social-justice principles: “I see the church as really needing to be the voice of love and unity and acceptance, and so it feels like this might be a good match for us.”

For now, Capitol Hill Presbyterian’s congregation is mostly administering palliative care, with the church members soothing each other as best they can. “It’s like getting the diagnosis, stage 4 cancer,” Kuepker lamented about the church’s impending closure, “so you just wait.”