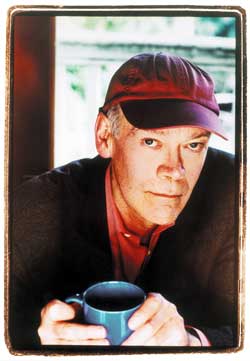

Jonathan Raban moved from London to Seattle in 1990. His recent books include Hunting Mister Heartbreak, Bad Land, Passage to Juneau, and the forthcoming Waxwings. An earlier work, Arabia: A Journey Through the Labyrinth, was published in 1979. This article originally appeared March 22 in the Guardian of London.

US public hardens behind war but radical fringe finds its voice, read a headline in the Guardian last week. Not trueor at least not true in my corner of the U.S., where the leafiest and richest suburbs were thickly placarded with No Iraq War signs, and where, on weekend protest marches against the Bush White House, prosperous bourgeois families, more usually seen tramping around the downtown art galleries on the first Thursday evening of each month, hugely outnumbered the bearded peaceniks of the radical fringe. A couple of weeks ago, Speight Jenkins, the general director of the Seattle Opera, told Seattle Weekly that in the course of a season of heavy fund-raising he hadnt so far encountered one person who was in favor of the war: Fringe radicals are not usually people who can fork out seven-figure checks to keep the Ring Cycle going. At the private elementary school attended by my daughter, No Iraq War bumper stickers adorn the Range Rovers and Toyota Land Cruisers of the soccer moms, along with slyer, milder protest slogans, like Carter for President in 04. At dinner parties and in public meetings, the prevailing mood before March 19 was pitched somewhere between aghast hilarity and downright despair as Seattle awaited a war in which it appears to want no part at all.

Some of this might be put down to simple provincial isolationism: Squatting on its deep backwater of the Pacific, walled-in by mountain ranges, 2,800 miles from Washington, D.C. (known here, without affection, as the other Washington), Seattle is congenitally suspicious of enthusiasms hatched inside the Beltway. But its view of the larger world is shaped by a different ocean. When Seattles sleep is disturbed by geopolitical bad dreams, it is more likely to be visited by the specter of Pyongyang (to which it is the nearest big city on the American mainland) than Baghdad. For Seattle, militant Islamism begins in Indonesia, not North Africa or Arabia, and Indonesian container ships dock at a terminal which, from the point of view of an Al Qaeda operative, is conveniently located right next to the downtown business district. The city is a potential sitting duck for terrorist dirty bombs and for North Korean nuclear warheads, but the threat posed by Saddam Hussein and his weapons of mass destruction seems remote.

Seattle is a liberal-Democratic stronghold. The 7th Congressional District, which includes the city along with a good chunk of its suburbs, is a constituency so comfortably settled in its voting habits that the congressman from Seattle can afford to voice left-leaning opinions that would have most of his House colleagues quickly booted from office. The incumbent, now in his eighth term, is a cheerfully uninhibited exchild psychiatrist named Jim McDermott who rather resemblesif you can imagine such a thingTam Dalyell with working-class cred. McDermott has been known as Baghdad Jim since last autumn, when, interviewed on live network television from Iraq, he lectured America on the number of infant deaths caused by sanctions. He seems to rejoice in the nickname. The states senior senator, Patty Murray, born and raised in the Seattle suburbs, got into big national trouble when the Drudge Report publicized her meeting with a group of high-school students in Vancouver, Wash., where she asked the kids to consider the very Seattleish question of why Osama bin Laden should be widely regarded as a folk hero in the Middle East. (Answer: He invested in the local infrastructure in Sudan, Yemen, and Afghanistan, and we havent done that. For a few days, all hell broke loose on the right-wing talk-radio stations.) Long ago in the 1930s, FDRs postmaster general, James A. Farley, remarked that there were the 47 states and the Soviet republic of the state of Washington, and Seattle likes to deliver occasional reminders that it was once the headquarters of the Industrial Workers of the World, the Wobbliesas it did in 1999 with the WTO demonstrations.

That said, Seattle is by no means anti-war in general. It houses the main plant of Boeing, the company that made the city rich in World War II. Its ringed with large military basesthe naval air station on Whidbey Island, naval bases at Everett and Bremerton, the Army base of Fort Lewis and McChord Air Force base near Tacomaand military spending of one sort and another puts $8 billion a year into the state economy. There was an almost-daily slot on the local TV news for pictures of tearful farewells on the bases as the forces deployed for the Gulf and of toddlers waving handkerchief-sized American flags at the receding sterns of aircraft carriers sailing north up Puget Sound. The signs saying Support Our Troops and No Iraq War are complementary rather than oppositional. It is this war for which Seattle has little or no stomach.

Theology comes into it. When I first moved here, I cherished the fact that Seattle has one of the lowest churchgoing rates in the nation, and when it does go to church, it likes its religion to be on the cool and damp sideLutheran, Catholic, or Episcopalian, for preference. On his Web site, McDermott cautiously admits that he attends the Episcopalian cathedral of St. Marks, which diplomatically excuses him from owning up to any particular belief, or disbelief, in God.

President Bush, who talks of his relationship with Jesus as if theyd been Deke fraternity brothers in college and casts himself as Gods personal instrument in the war against evil, may warm the hearts of his Bible Belt supporters, but he offends in Seattle, where Christian, hardly less than Islamic, fundamentalists tend to be viewed as people whove taken a good thing a great deal too far. In this reserved, northern, Protestant (though not that Protestant) city, Tony Blairs moral eloquence on Iraq meets with a kind of puzzled admiration, while Bushs narrow televangelical fervor arouses much mistrust, for he speaks in a language more often associated here with charlatans than honest pastors. To the Seattle ear, George Bush sounds an awful lot like Jimmy Swaggart.

If that applies to Bush, it applies even more strongly to the secular absolutists and visionaries by whom he is surrounded and especially to Paul Wolfowitz and Richard Perle, who pop up everywhere, propounding the case for invasion. God doesnt specifically figure in Wolfowitzs big-picture vision of a born-again Arab world, but the terms in which his great plan is phrased are both religiose and fundamentalist. In Wolfowitzs version of the domino theory, democracy is a contagion spreading through the Middle East after the (effortless) conquering of Iraq. Iran, Syria, Saudi Arabiastate after state goes down with democracy, each falling on the next with a gentle click. Establish Connecticut-on-the-Tigris, and the rest follows with an inexorable logic of the kind that operates only in dreams and revelations. It is all, as Bush would say, faith based.

It will also cost us little or nothing. I lost a couple of hours sleep a few days ago, when at 11:30 p.m. I switched from the local news to C-SPAN and happened on Wolfowitz answering questions from a captive audience in a Californian think tank. With the glint of fanatic certitude in his eye, he was explaining how both the invasion of Iraq and its reconstruction would be comfortably paid for by its own oil supplies. Win-win. A no-brainer.

Listening to him, I thought: This kind of talk comes two years too late for Seattle.

For the city is currently going through a phase of chastened realism. Until the Nasdaq Index began its long slide in March 2000, taking the stocks of local companies like Amazon.com and RealNetworks down to pathetic fractions of their previous value, Seattle was on a delirious roll and full of true believers in the magic of the New Economy, which generated profit from loss and made instant millionaires of everyone with five or 10 thousand stock options. For Seattle, the dot-com boom was a reprise of the Klondike gold rush in the 1890s, which funded the building of most of the landmark historic (this is a young city) houses and office blocks in town. It set off another wave of grandiose construction, much of it still waiting to be occupied and paid for.

For Sale signs have given way to ones saying For Rent. Hotel lobbies have an eerily deserted air. Restaurant tables go begging, and many once-packed joints have given up and closed their doors. The erstwhile paper millionaires are keeping busy mailing out their r鳵m鳬 for the Seattle area, which at the turn of the millennium had one of the most buoyant economies in the nation, now heads the nations unemployment rates. This isnt meant to suggest that Seattle now looks like, say, the urban northeast of England in the early 1980s, with the mass closure of coal mines and factories: Its not like that, and theres still an enormous amount of wealth concentrated here. But since March 2000, the city has been digesting the hard lesson that money does not, as it once did, grow on trees.

Once bitten, twice shy. Having just breathlessly stepped off the roller coaster of the New Economy, Seattle is wary about being taken for another ride aboard the New World Order. The Wolfowitz scheme for the market-democratization of the Middle East rather closely resembles the kind of untested business plan for which venture capitalists here used to hand over millions of dollars without a second thought in the heady days when the Internet was going to make supermarkets redundant, and Seattles household chores were all going to be performed by MyLackey. com (when MyLackey went broke, it was said that its biggest problem was that few people had any clear idea as to what a lackey is or was). Seattleites are thoroughly familiar with the strategy of shock and awe: You have to begin with a massive burn rate in order to establish a global footprint, at which point the enterprise begins to pay for itselfexponentially. Except that most such enterprises ended up filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, and so did the venture capitalists who funded them.

It used to be a point of Seattle principle that every spectacularly successful venture begins life in somebodys garage. You had only to say the word to evoke the spirit of Jeff Bezos and Amazon. Thats true no longer. One thing seriously wrong with Paul Wolfowitzs business plan is that it bears all the marks of having been cooked up in a garage.

Seattle has two daily newspapers. Ownership of The Seattle Times is split between the Knight Ridder publishing empire and a local family, the Blethens. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer is owned by the giant Hearst Corp., which is hardly famous for its liberal bias. In October 2000, the Times narrowly endorsed the presidential candidacy of George Bush for his civility, integrity, and understanding of the dynamics of taxes, regulations, and enterprise that form a successful business. The P-I endorsed Gore, for his experience, knowledge, and philosophy, and because we have grave misgivings about the breadth and depth of Bushs grasp of the essential knowledge required of the president and commander in chief of the worlds sole superpower. Neither paper is politically predictable. Though the P-I generally sits somewhat to the left of the Times, both papers usually endorse a fairly equal number of Republicans and Democrats. Both are now severely critical of the Bush administration, and one has squarely opposed the invasion.

After the president gave his brink-of-war press conference on March 6 (This is the last phase of diplomacy . . .), the P-I editorial board took a communal deep breath and announced themselves unpersuaded by Bushs case. We were eager for clarity and precisionand it was not to be. . . . Bush . . . has left us discomfited. . . . We, like many Americans, remain unconvinced of the direct connection between Al Qaeda and Iraq, or that Iraq presents a clear and present danger to us. The editorial ended: Its time for people to show their cards, Bush said. Were left wondering if he really understands the stakes.

The Times, in keeping with its business-minded endorsement of Bush in 2000, attacked the president for his evasive accounting procedures. The Bush administration is dodging the cost of war with Iraq as studiously as Saddam Hussein is hiding chemical and biological weapons. . . . The administration is running a tab without disclosing what the costs have been. . . . The White House obviously suspects its figures might complicate support for the war. That is a politic instinct, but it is inappropriate in a democracy that thrives on information. It is also just plain wrong. The subtext here is that Washington, like many other states, is this year facing a massive budget shortfall, requiring deep cuts in services like education, health, child care, and policing. The National Governors Association recently put out a report saying that nearly every state is in fiscal crisis. So the prospect of Americas hitherto untraveled president going abroad, at taxpayers expense, on an adventure of untold, untellable cost, comes at a singularly bad moment for the individual statesand especially for Washington, whose New Economy tax base has been steadily shriveling over the last two years. In basic housekeeping terms, Seattle and the White House are living in different worlds.

Over at the P-I, where resistance to the war is rooted more in mistrust of its moral and political objectives, the most heartfelt and persistent criticism of the administration has come from David Horsey, the papers Pulitzer Prizewinning cartoonist, whose drawings of the 43rd president show him as a scrawny, simian-featured homunculus with a childish predilection for dressing up; now as Caesar, now as Napoleon, as a western gunfighter, as a tin-hatted soldier-hero from the Normandy beaches. Caught in private, in plain shirt and khakis, Horseys George Bush resembles the unprepossessing night clerk in a convenience storea Walter Mitty figure, ridiculously too small for his office. Horsey took a year off to study international politics at the University of Kent at Canterbury, and his cartoons are more conceptually elaborate than most. Here, for instance, is Bush the huckster-showman, wielding a distorting fun- house mirror to vastly magnify the small, torpid rat labeled Saddam Hussein, and inquiring of his audience, Are you scared enough yet? Heres bin Laden on his prayer mat, addressing a shopping list of requests to God, and finding that George W. Bush is the answer to all his prayers. Heres Bush in the same position, coming to the bewildered conclusion that God must be a Frenchman. In Leader Without a Compass, Horsey depicts Bush as a pith-helmeted adventure tour guide, dragging an unwilling young woman named America, unsuitably dressed in beach-vacation wear, through a jungle infested with dangerous beasts, of which much the least threatening is the sleepy crocodile of Iraq. In The Bush Victory Garden, the tender seedling of Afghan democracy has died in a landscape of cracked mud, while the thistles of opium farming, warlords, and Al Qaeda are in vigorous bloom. Bush looks up from a creased map of Iraq to ask Kim Jong Il, who is perched on the nose cone of a North Korean warhead, Say! Do you know a good back road to Baghdad? On a local note, Every Party

Needs a Pooper has a roomful of pie-eyed inebriates, drunk on war, being visited by Congressman McDermott holding a pot of coffee labeled Inspections First. For Christmas, Horsey drew two children dreaming in their beds: The American child dreamed of Santa coming down the chimney; the Iraqi child dreamed of an American missile taking the same route. Ive seen angrier cartoons in the British press, but none that offer such a thoughtful range of reasons for dissent. Horseys work can be seen on the Web here.

One measure of the P-Is emerging position on the war is that, since March 18, they have been running Robert Fisks reports from Baghdad for the Independent. Fisk! His skepticism about American intentions in the Middle East sets him apart from all other British, let alone American, correspondents; it is as if the P-I, after listening to Bushs address to the nation March 17, had turned to Jacques Chirac for a more enlightened view of things.

For another authentic Seattle voice, one might listen to Stimson Bullitt, the veteran soldier, lawyer, mountaineer, developer (Harbor Steps), and 1954 Democratic candidate for the U.S. Congress. In an e-mail responding to a draft of this article, he wrote:

There have been a few American presidents with lower competence [than Bush], but none as harmful. As a teenager in the 30s I heard intelligent business and professional men grumblingno, asserting with passionthat FDR and his policies were going to ruin our country, take it to destitution and despotism. Now, of course, Im convinced that they were wrong, yet a still, small voice asks, By chance, could you be as wrong now as they were then? No, I dont really think so. The years 4045 stirred me deeply, as they did most of us back then, but no public events in my life have upset me as much as the current national leadership.

The economic profligacy and environmental outrages will make us suffer but from them we can recover. What troubles my sleep is the whirlwind we can expect to reap from abroad the next few years. Awareness of my short life expectancy is only a minor consolation.

The United States is the least monolithic country on Earth, and youre bound to get a skewed picture of the nation at large from inside the perspective of just one of its myriad quarrelsome constituencies. From where I live, there appears to be no very significant gulf between American and European opinion: So far as I can fairly judge it, Seattles position on the invasion of Iraq differs little from that of, say, Bristol or Manchester, or even Hamburg or Lyon, though it is seriously out of sync with that of Washington, D.C. Yet Seattle does not believe itself to be on the radical fringeand I have a hunch that Id be writing in a very similar vein if I were living in Des Moines, Iowa, or any one of a dozen provincial capitals in the U.S.

Suspicion of the national polls has hardened into outright disbelief. You can get a poll to say any damn thing you want, McDermott said the other day; but theres more to it than that. In the climate of John Ashcrofts new security state, the question, Do you support the presidents policy on Iraq? asked over the phone by a faceless pollster, easily mutates in the mind of the citizen to, Are you a patriot? or even, Do you want to get in trouble? As Bush has put it, either you are with us . . . , and in the wake of 9/11 it troubles Americans to own up to being against the administration. Which does not mean that they are for it.

There is also much anger with the Democrats for failing to provide any articulate leadership in the war on (not with) Iraq. To many of its traditional supporters, the party appears to have been gutlessly complaisant in its bipartisan stance. But something interesting happened on Feb. 21, when the present crop of presidential hopefuls paraded in front of the Democratic National Committee in what several reporters likened to a beauty pageant. Joe Lieberman made a speech so flat that his candidacy may well have died in that moment. Richard Gephardt boasted of making common cause with the Bush administration on Iraq, and was met with cries of Shame! but went on to outline his domestic policy and won a series of standing ovations. Then came Howard Dean, the former governor of Vermont.

Im Howard Dean, and Im here to represent the Democratic wing of the Democratic Party. . . . What I want to know is why in the world the Democratic Party leadership is supporting the presidents unilateral attack on Iraq.

Deans opening remarks were enough to leave both Lieberman and Gephardt in the dust. The hall was in an uproar of approval and relief. At last a reasonably qualified and plausible presidential candidate was saying something that rank-and-file Democrats have been waiting to hear for many months. The immediate upshot of his speech (by no means limited to the war) was an orgy of text-messaging from state delegates to their party officials back home, saying that Gephardt had rescued himself after a bad start, Lieberman had flopped, and Howard Dean had carried the day gloriously, on the economy as much as on the invasion of Iraq. Dean is far from being a Gene McCarthy figure; he comes with a raft of policies, one of which happens to be about the war. In the last month, he has moved from being an utterly obscure figure to anyone not from Vermont to being a neck-and-neck front-runner in the Democratic nomination race. If this has come as a surprise to most national political commentators, it doesnt seem at all surprising if you happen to live in Seattle.

We are all Americans now. Le Mondes headline two days after 9/11 has been much quoted as a reminder of how disastrously the Atlantic alliance has broken apart in the course of the last 18 months, and of how wantonly the Bush administration has squandered the worlds goodwill toward the United States. Yet living in the United States, far from the Beltway, Im struck by how many Americans have become no less alienated than the great mass of British, French, Belgian, or German voters by the American governments stand on Iraq. A few days ago, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer ran an editorial headlined (with no irony at all intended), Vive la France, friend and ally. On this issue, a surprising number of Americans feel that they are Europeans now.

With Baghdad ablaze and American tanks racing through the Iraqi desert, public opinion inevitably began to harden in favor of the administration, and will further solidify when the first remains of Americans are brought back to the U.S.in body bags if theyve been killed by conventional weapons and probably in urns if theyve fallen to biological ones. Everyone must now hope for a swift military victory, if only to halt the destruction of Iraqi cities and minimize the loss of life on both sides. Yet there will still fester the sense that this is a grossly unaffordable war, an immoral war fought on a policy wonks fantastic premise that democracy could be imposed by brute force across the Middle East, a war that kindled the worlds enmity toward the United States and recruited thousands of volunteers for terrorist organizations like Al Qaeda. In six months time, I doubt that convictions now so widely held in this West Coast city will be seen as the property of a radical fringe. Watch Howard Dean.