EVERETT — A jury began deliberating Tuesday in the landmark trial of a trucker accused of killing a young Canadian couple in 1987.

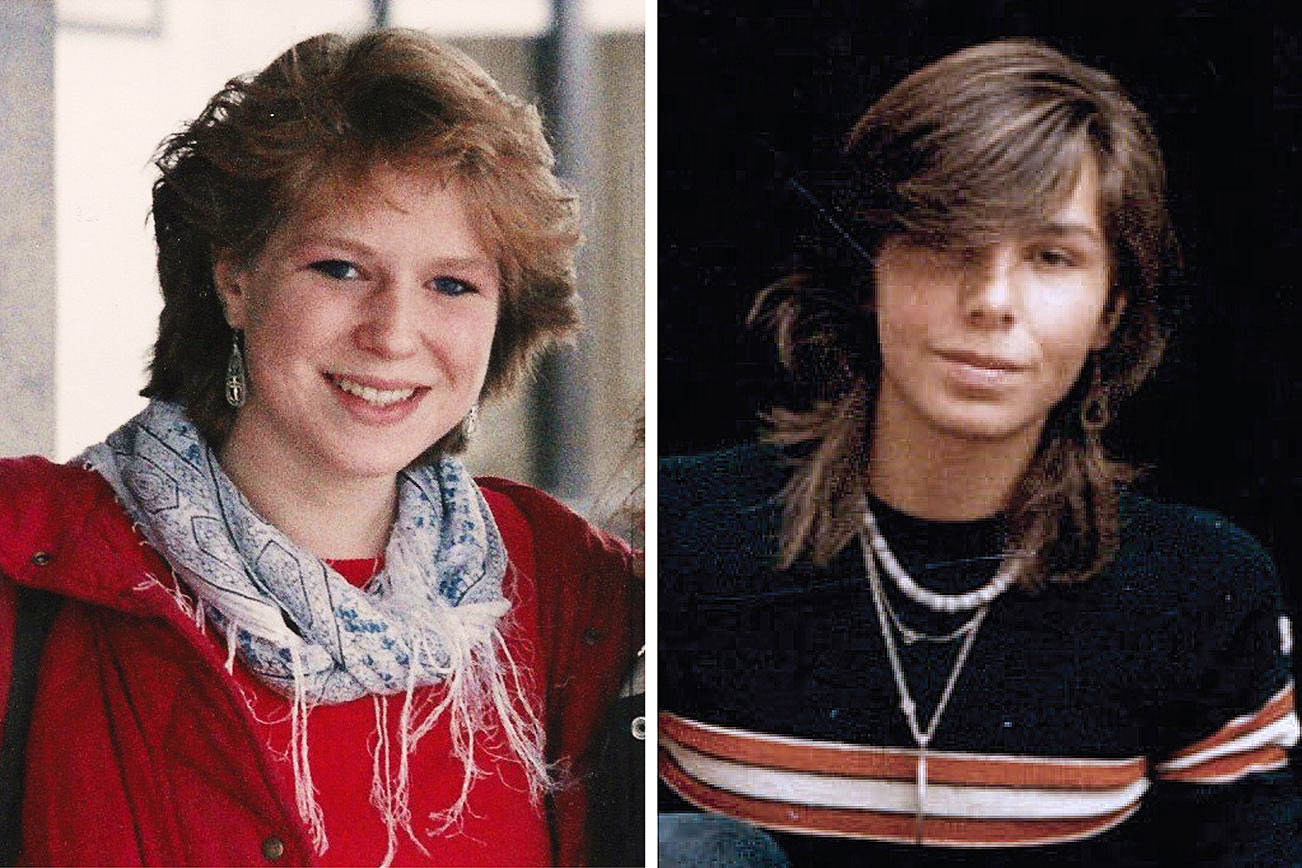

Deputy prosecutor Matt Baldock dimmed the lights and projected high school portraits of Jay Cook and Tanya Van Cuylenborg on the courtroom walls.

His closing argument began with questions.

What might their lives have looked like?

Would they have traveled the world?

Would they have had children?

“These are all questions that their family and friends have asked, more than once, in the softer moments,” Baldock said. “But there are also questions that they have asked over and over again, over the past 31 years — questions that frame their grief and their loss.”

Did they know they were going to die?

Did they suffer?

Why would someone commit such violence against them?

The families of Cook, 20, and Van Cuylenborg, 18, may never know specifics of what happened, Baldock said. But he argued that one question was answered.

“Who did it?”

William Talbott II, 56, of SeaTac, chose not to testify Tuesday. He’s accused of two counts of aggravated first-degree murder.

His attorneys called only one witness, a defense investigator, who answered questions for about 10 minutes.

The state called no rebuttal witnesses.

Jurors had heard about 1½ weeks of testimony from police, family members, store clerks and people who had found key evidence.

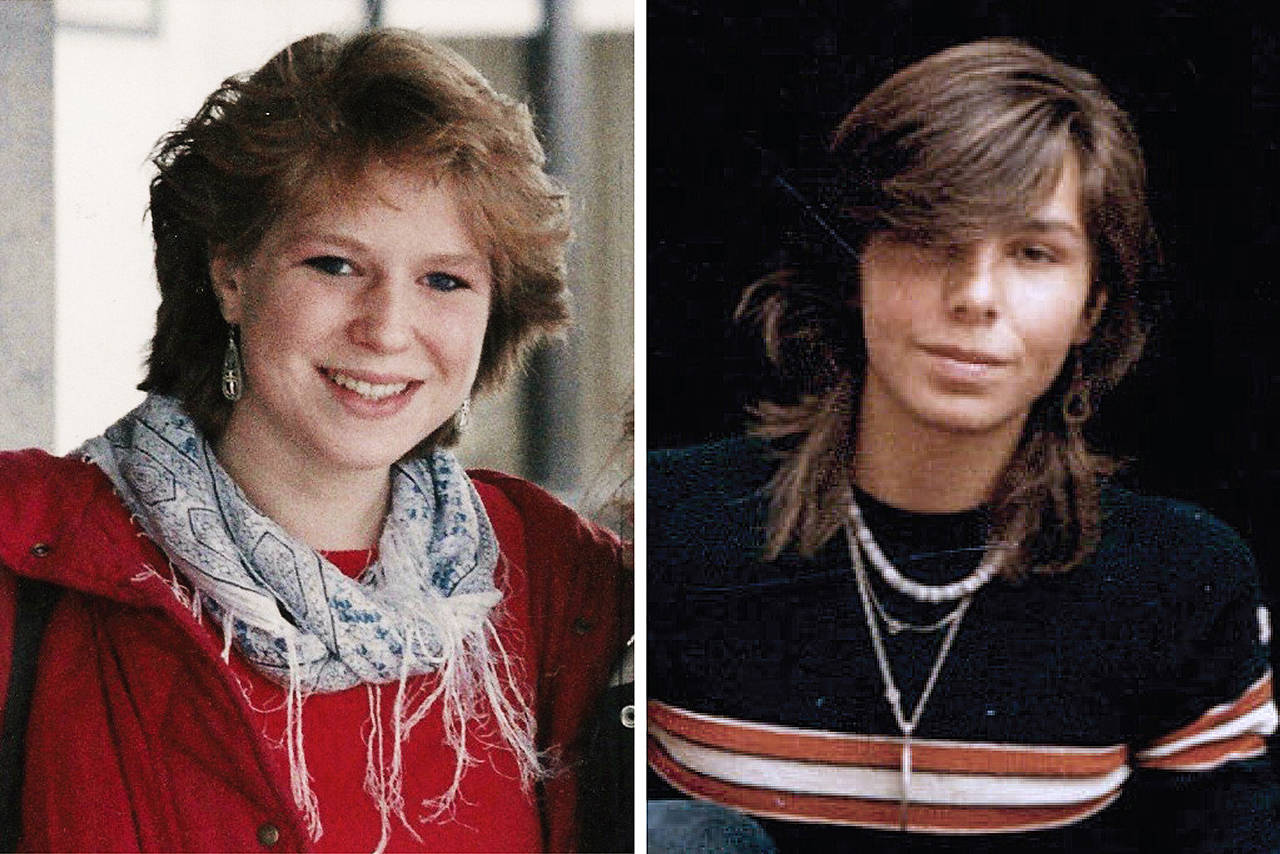

For closing arguments, a crowd filled every seat in the courtroom gallery and spilled into the aisles.

The Vancouver Island couple had been dating a few months by Nov. 18, 1987, when they took a road trip to Seattle to pick up furnace parts from Gensco, a business south of the Kingdome. Their route traced the shorelines around Puget Sound. Their ferry from Victoria landed in Port Angeles around 4 p.m., with perhaps an hour of daylight left in the sky. They drove past an exit, asked for directions in Hoodsport and rerouted to Allyn on their way to Bremerton.

The last clue that they were alive was a ticket for the Bremerton-Seattle ferry. That boat docked in Seattle just before midnight.

The couple never finished their errand.

Van Cuylenborg’s body was discovered Nov. 24, 1987, in rural Skagit County. She’d been shot in the back of the head. Semen was found on her body and on a pair of pants that belonged to her.

She’d been raped and executed, Baldock said.

“Coming up with some other alternative explanation would push the limits of logic,” he argued.

Cook was found dead — beaten and strangled — two days later under a bridge south of Monroe.

Throughout the trial, the defense noted the days following the couple’s disappearance were unexplained gaps in the prosecution’s timeline.

“They want you to fill in the gaps,” defense attorney Rachel Forde said in her closing argument.

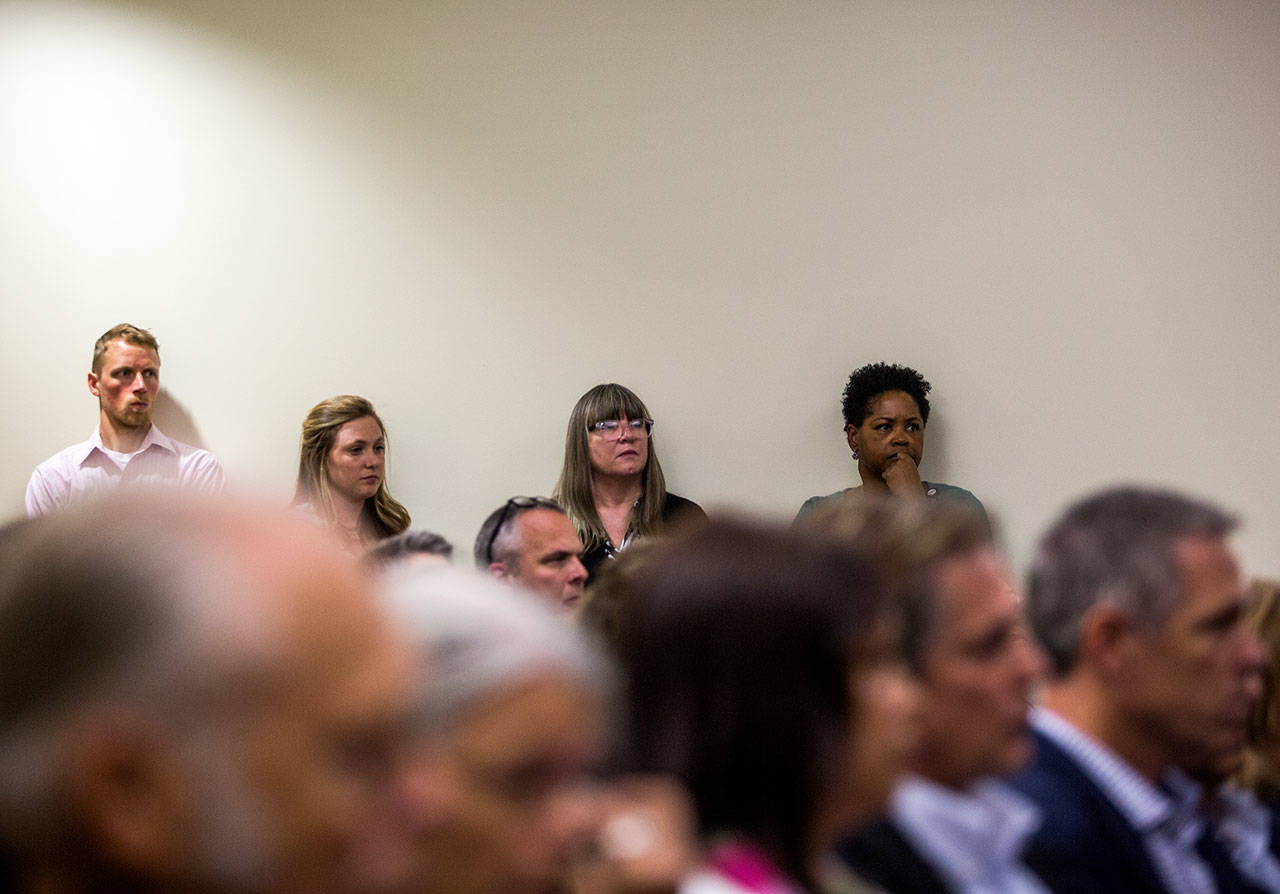

At both scenes, police found interlocked zip ties. More zip ties had been tied together in the Cook family van, a Ford Club Wagon, when police discovered it parked in downtown Bellingham.

“If there was any question that these murders were connected, there cannot be, when you consider this evidence,” Baldock said.

The defense suggested Talbott’s semen could have ended up at the crime scenes — on pants in the van, and on Van Cuylenborg — from consensual sex.

Forde said police developed “tunnel vision” over the years, clearing people as suspects because their DNA didn’t match the semen.

“They never stopped to consider,” Forde said, “that perhaps the person who left the DNA was not the murderer. ”

She conceded Talbott had sexual contact with Van Cuylenborg.

“We can say that,” Forde said.

But that’s not enough, she argued, to convict him of murder.

In a pioneering investigation, detectives had linked Talbott to the killings in 2018, through a technique known as genetic genealogy. A private lab uploaded crime scene DNA onto a public ancestry site, and a genealogist built the suspect’s family tree, based on second-cousins who had uploaded their genetic profiles to GEDMatch.

The investigation pointed to Talbott. The match was later confirmed with DNA samples from Talbott’s mouth, according to witness testimony.

Forde argued it was only when police stopped Talbott at his workplace in May 2018, after a busy day of truck deliveries, that he learned about the killings.

“That is the first and only salient moment for him, in the web that the state has woven for you,” Forde said.

Earlier on, prosecutors had warned jurors that they would have questions at the end of the trial.

“That was an understatement, to say the least,” Forde argued. “You have many, many questions about what happened to Jay and Tanya in 1987, and none of those have been answered.”

The gun used to kill Van Cuylenborg was never recovered, and Talbott wasn’t known to own guns.

Dog collars used to strangle Cook weren’t shown to belong to Talbott, and he wasn’t known to own dogs.

Neither of the Canadians had injuries on their wrists from zip ties — suggesting that there was no struggle, Forde said.

And in the defense’s view, the state did not establish a motive for the killings.

Forde countered a state crime lab’s conclusion that Talbott left a palm print on the the van. Police had also found gloves near the van in Bellingham.

“If Bill Talbott was the killer (and) he had gloves, why did he leave a palm print?” Forde asked the jury.

The state crime lab worker said on the witness stand she’d ruled out Talbott as the source of the print — until she realized she was looking at it upside down.

In the 1990s, Talbott had rented a room from a cop.

“Someone who had just brutally murdered two people and had gone undetected would not rent a room from a police officer,” Forde said. “He just wouldn’t.”

Snohomish County Superior Court Judge Linda Krese had denied a defense motion early Tuesday to dismiss both charges. Another one of Talbott’s attorneys, Jon Scott, argued there was no evidence directly linking the defendant to Cook’s homicide.

“It’s like multiplying by zero,” Scott said.

Krese, however, noted the couple had last been seen in each other’s company, and evidence from the crime scenes suggested a link between the two killings.

For example, a pack of Camel Lights had been stuffed down Cook’s throat. The same kind of cigarettes were found in the van.

Krese left it to the jury to decide if Talbott was guilty or not.

The defense’s lone witness, Todd Reeves, is an investigator who works with Scott. He testified Talbott’s past driver’s licenses showed an address in Riverside, a town in Okanogan County where the defendant owned land.

Under cross-examination, Reeves testified Talbott resided in SeaTac at the time of his arrest, though none of his official records reflected that.

The defendant grew up in the Woodinville area.

The lead detective in the case, Jim Scharf, testified this week that Talbott’s parents lived seven miles from the rural bridge where Cook’s body was dumped.

According to the defense, someone who knew the area would’ve found a better place to hide a body.

At the time of the killings, Talbott was 24.

In his rebuttal, Baldock said the defense had made a stunning argument, that we don’t know who the couple encountered that week in November 1987.

He pointed at the defendant.

“They crossed paths with him,” Baldock said. “We know that, without a doubt.”

The jurors walked into a room on the second-floor of the courthouse around 4 p.m., to start deliberating.

Caleb Hutton: 425-339-3454; chutton@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @snocaleb.