Joshua Shelby Dawson is your stereotypical local weapons peddler: an inner-city black kid from a broken family who grew up around guns. His best friend was shot to death, and, as a Seattle teenager, Dawson himself took a bullet in the back. He was convicted as a juvenile of a carjacking in which he held a gun to the victim’s head. Last year, a jobless felon with a pregnant girlfriend, he turned to selling guns. He joined five others who stole most of their weapons and resold them on the street—sometimes, unfortunately for them, to an undercover federal informant.

Dawson trafficked in hot street handguns, one of which was subsequently used in a January 2012 shooting in South Lake Union. The gunman was arrested after three young men were seriously wounded and several cars were struck by bullets outside the nightclub Citrus, which this month was declared a “chronic nuisance” and faces closure by the city due to that shooting and other crime incidents. But Dawson also saw himself as a potential international gun supplier of drug-war arms. The federal informant, posing as an associate of a Mexican narcotics cartel, offered to buy high-powered weapons for use against Mexico’s federal police. Dawson was able to come up with four assault rifles that had been stolen in a residential burglary.

When the sting came down and officers went to arrest the 20-year-old father-to-be last April, he tried to flee in his car, crashing it into other vehicles. He was arrested at gunpoint by officers who found a loaded 9mm Kel-Tec pistol in his glove box. Dawson was in jail awaiting trial with his five co-conspirators when his girlfriend gave birth to their daughter in July. He turned 21 in December. Last month, his relatively brief gun-trafficking career over, he went off to prison.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Nicholas Brown told a federal judge that Dawson had “the capacity for violence and an affinity for firearms.” Dawson said that wasn’t the real him. He apologized for his weapons dealing, telling the court “I am ashamed to be here because I was not raised to sell guns.” It wasn’t convincing.

“You were directly involved in providing firearms that would hit the streets without any concern of where they would go or how they would be used,” said U.S. District Judge Richard A. Jones. He gave Dawson a five-and-a-half-year sentence for illegally selling eight weapons and being a felon in possession.

Federal officials say the bust of Dawson and his fellow gun-runners took 25 weapons off the street, along with a silencer. The gang of six took advantage of the underground arms market made possible by the gun-show loophole and other systemic gun-tracking failures. Such off-the-book sales—done without a Federal Firearms License at shows or on the streets—led to an untraceable void. In such cases, neither the transaction nor the weapon’s trail are recorded, and the gun effectively falls off every radar the government has.

As it is, no one knows who buys, sells, and owns most of America’s 300 million firearms. Congress, lobbied by money-bearing gun-rights groups warning of door-to-door government gun grabs, long ago forbade the creation of a federal gun registry. As the gun-control debate grew louder in the wake of the December 14 Newtown, Conn., school massacre by a gunman using a military-style AR-15 semi-automatic rifle to kill 20 first-graders and six educators, groups such as the National Rifle Association grew even stiffer in their resistance to change. President Barack Obama’s gun-control proposals were quickly rejected by a suspicious NRA, which sees Obama’s proposed universal background checks and other measures as a move toward creating that feared central gun registry.

Today, therefore, only after a weapon has been used in a crime can the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms even begin to record some of its history, and even then it’s a low-tech trail. As Charles Houser, who runs the ATF’s National Tracing Center in West Virginia, recently told The Associated Press, “It’s not CSI and it’s not a sophisticated computer system.” Some of the records, he said, are actually stored as digital pictures that can only be searched one image at a time. The “manually intensive process” of a routine search sometimes takes five days, and can include sorting by hand through old paper records.

In the Dawson case, the stolen guns were returned to their owners and their serial numbers entered into the ATF system. They can now be traced—should they show up in another crime.

Dawson has a more durable tracking number: inmate 41543-086, traceable until November 2016 within the U.S. Bureau of Prisons system. He’s currently at the Sea-Tac Federal Detention Center. Court paperwork indicates he will wind up at the minimum-security facility in Florence, Colorado.

There he could share the grounds with Roy Alloway, who arrived at Florence, 90 miles south of Denver, last February. Alloway was a gun runner, too. But unlike Dawson, Alloway, a 58-year-old white suburban grandfather with an otherwise clean record, didn’t fit the stereotype.

In fact, he may be the Northwest’s most untypical illicit gun dealer ever.

Whereas Dawson sold eight guns in a few months without a license, Grandpa Alloway sold more than 700 in a few years, although federal officials say the true number may be closer to an astonishing 2,200 guns.

But then, Alloway had the advantage of wearing a badge. He was a cop, supposedly on the other side of the law from Dawson. Yet as a local police officer and a detective on a federally backed drug task force, he could exploit an opportunity Dawson never had: the police loophole.

Law-enforcement agencies are allowed to sell guns seized at crime scenes or otherwise discarded to pad their coffers—a legalized form of crime-gun redistribution that brings embarrassment on the departments when the resold weapons are used for violent crime. Most departments have policies controlling who buys their guns, limiting sales to major dealers. But the system still allows an unscrupulous insider like Alloway to put the guns back on the streets.

In what is now considered a legendary instance of gun-running, Alloway worked within that system to peddle his weapons, some of which later showed up at crime scenes. And by operating out of gun shows watched over by fellow law-enforcement agents rather than working the jittery backstreets of Seattle, he was able to keep suspicious investigators at bay far longer than small-time dealer Dawson could dream of doing.

In January 2001, Aryan Nations white supremacist Buford Furrow Jr. was sentenced to life in prison without parole for his blood-spattered hate-crime assault on the North Valley Jewish Community Center day-care facility near Los Angeles. He wounded three children, a receptionist, and a counselor in the 1999 assault, using several clips to fire 70 rounds with a 9mm Norinco semi-automatic rifle, originally designed for the Israeli Army. While fleeing, he stopped and used a Glock 9mm handgun to kill a Filipino U.S. Postal Service carrier, shooting him nine times because he was nonwhite and worked for the government.

A native of Lacey, Furrow had driven south from Tacoma, where he’d bought a used Chevrolet van and loaded it with a small arsenal of weapons, thousands of rounds of ammo, and an armored vest. After the shootings, he dumped the van and took an $800 taxi ride to Las Vegas, where he turned himself into the FBI, saying he hoped his actions would be “a wakeup call to America to kill Jews.”

To no one’s surprise, Furrow turned out to have spent some months prior to the shooting in a Seattle psychiatric ward and being examined by doctors at Western State psychiatric hospital. He told doctors he’d fantasized about committing a mass murder. He eventually was turned loose and told to take his meds.

So where did the mentally disturbed killer get his weapons? Furrow, it turned out, had been a federally licensed firearms dealer from 1992 to 1995, and likely stockpiled weapons. The rifle used in the North Valley shooting was not traceable. But the Glock used to murder postal worker Joseph Ileto was. Though he had a felony conviction and could no longer lawfully possess a weapon, Furrow was able to buy it from an unlicensed dealer at a Spokane gun show. The Glock had passed through the hands of several previous owners, but the original buyer, for $450, was the little Cosmopolis Police Department, across the bridge from Aberdeen in Grays Harbor County.

Then-Police Chief Gary Eisenhower told reporters that none of his officers liked the weapon because it was too light, so he traded it to a dealer for a bigger Glock. It wouldn’t have made economic sense to destroy a new weapon and buy a more expensive one, he said. Nonetheless, hearing of Furrow’s rampage, the chief admitted, “We’re just devastated. This is not something that we’d like to have notoriety for.”

It was a devastation that other police departments wanted to avoid, prompting departments around the nation to rethink their gun-sale policies. In Washington, under a state law revised in 1993, each city and county had the option to decide whether to put confiscated weapons up for sale or destroy them. Liberal Seattle already had a policy against reselling weapons, and in fact defied the 1980s state law that required police to sell forfeited weapons (instead, Seattle stockpiled its confiscated guns, at one point storing more than 8,000 firearms, then eventually melted them down after the law changed).

Following the L.A. shootings and policy changes, King and Snohomish Counties adopted policies similar to Seattle’s, and within a year Bellevue and other entities followed suit. Others didn’t, creating a crazy quilt of police gun-sale policies across the state. And the law still requires one agency to sell, not destroy, its surplus weapons—the Washington State Patrol. A majority of legislators, while granting local governments the option to destroy weapons, nonetheless felt it was a waste of guns and money for the WSP to do so.

State Patrol spokesperson Bob Calkins says the policy “has benefits to taxpayers.”

The patrol, in one sale last year, earned $42,000 in credit selling more than 200 guns to a licensed dealer. WSP will use the credits to buy guns or ammo for the department, “but another example might be something as simple as elbow pads for our SWAT team,” says Calkins. “It’s whatever we need that the dealer carries. Items made for police service can be expensive, and by trading we save the taxpayer a pretty penny.”

And, Calkins says, the sales are carefully managed, traded in bulk to “licensed gun dealers who have to do background checks for subsequent resale. We don’t do single-gun sales to individuals. We don’t trade weapons used in high-profile crimes. And we of course don’t trade weapons that would be illegal for someone to possess.”

Still, law-enforcement agencies in Washington have sold some serious weaponry. According to data contained in forfeited-property reports filed with the Office of the State Treasurer, which includes the police sale of confiscated guns, weapons recently sold by the Thurston County Narcotics Task Force included an AK-47 and a Norinco military-style rifle—the latter similar to the one Furrow had used to shoot up the day-care center. Central Washington University police sold a Bushmaster assault rifle similar to the weapon used by gunman Adam Lanza in the Newtown shootings.

And as Alloway’s case has shown, even under the strictest controls, government agencies cannot keep close track of where weapons go after they sell them, until they wind up in the type of crime scenes that police endeavor to prevent.

Stats as basic as the number of guns sold annually by Washington police to licensed dealers aren’t kept by the state. The State Treasurer’s office monitors only whether cities and counties have paid the state the required 10 percent on the sales. “Each police department files its report and includes a check for 10 percent of all the forfeited property they sell, including cars, motor homes, or whatever,” says office spokesperson Chris McGann. “They include the itemized list, but all we really track is the check.”

One such check in a recent batch of records was reported by the West Sound Narcotics Enforcement Team, known as WestNet—the antidrug crime team that Alloway was assigned to for most of 10 years. It’s anyone’s guess whether any of the $3,800 in handguns WestNet sold during a three-month period in 2011 eventually found their way to Alloway’s hands and America’s murky gun markets.

But there’s no doubt that over the years, the cop funneled dozens of WestNet guns, and perhaps thousands from other sources, into that private morass.

When the news first broke that Roy Alloway, celebrated narcotics officer, had been arrested for running more than 400 guns in recent years, people were amazed. But, Seattle Weekly has learned, further investigation would show that wasn’t the half—or even the quarter—of it.

Consulting Alloway’s confiscated private sales records, federal agents were eventually able to track his sale of 743 guns from 2004 into 2010. During the last four years of that period, he deposited almost $180,000 from his gun business, paying no taxes on the proceeds.

As the office of U.S. Attorney Jenny Durkan explains, those numbers were lowballs. The number of guns Alloway actually sold could be “at least two times greater,” according to Assistant U.S. Attorney Bruce Miyake. That works out to a minimum of 2,229 weapons.

In an interview, Miyake, who prosecuted Alloway last year, says, “There was no complete record of the number of guns he sold in the secondary market,” due to the gun-show loophole that allows unrecorded sales by an unlicensed gun dealer. “But in talking with some of the people who went to the gun shows, and some of his friends who were familiar with his sales, investigators were able to determine he sold many, many more guns” than 700, Miyake says.

“People at the gun shows warned him about selling so many guns,” Miyake adds. “They were amazed that he got away with it for so long.”

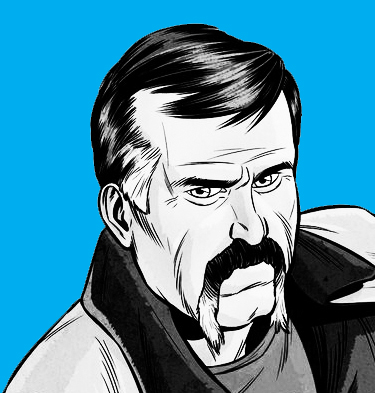

Alloway, heavily built with small penetrating eyes and a handlebar mustache, became a Bremerton cop in 1978. A North Kitsap High School grad, he’d served in the Air Force during Vietnam, then worked at jails in Phoenix and Kitsap County. On the Bremerton force, he worked as a uniform officer and moved to an undercover drug unit in 1978. He told his hometown newspaper, the Kitsap Sun, that he was drawn to “the whole idea of blending into the criminal organization, and trying to do what you can to put them in check.” He hooked up with WestNet in 1998, operating out of the Kitsap County Sheriff’s Department, becoming what the Sun called the “go-to guy for grow ops.”

As the point man for WestNet, a splashy, federally funded state/local task-force operation whose choppers flew over marijuana grows from the Seattle suburbs to the Kitsap and Olympic peninsulas, Alloway was lauded by his fellow cops. But medical-marijuana producers considered him a notoriously overeager door-buster, earning him the questionable honor of having a strain of weed named after him, “Alloway 420.”

In a December 2011 profile of WestNet, the Tacoma News Tribune reported that one in five cases that the drug-busting “cowboys” of WestNet presented to prosecutors were insufficient to bring to trial due to weak or sloppy evidence. Though Alloway was a star of the drug team, he was “a long-term headache in his own department,” the paper found. “His personnel file reveals multiple suspensions and reprimands. Many revolved around ethical lapses and indifference to rules and legal procedure.” He often failed to show for court hearings, ran an aborted campaign for county coroner while still on the police clock, and allegedly sprayed mace on the car door handles of fellow officers he didn’t like.

It’s unclear when he began to focus on confiscated weapons for his own fun and profit. But as far back as 1992, according to Bremerton police records, Alloway was disciplined for dereliction of duty after he took two crime guns from the evidence room and traded them to a local gun dealer. Though the exchange was for weapons the department needed, the city attorney had warned that such swaps were illegal.

Alloway got the discipline overturned by an arbitrator. But as federal investigators have learned in recent years, the detective went on to spend a lot of time in the Kitsap County Sheriff’s property and evidence sections, on the prowl for weapons to buy and resell.

The sheriff’s office sold most of its seized firearms to a licensed Tacoma buyer known as Law Enforcement Equipment Distribution, or LEED. While LEED—which has an extensive online sales operation—offers some of its gear and self-defense products to the public, it limits sales of firearms (from semi-automatic pistols and submachine guns) to law-enforcement personnel.

But whether cops were buying weapons for police and personal use or for resale was another question. Alloway, for one, was reselling—and putting thousands of dollars into his pocket. At times, according to federal prosecutor Miyake, the detective would volunteer to transport firearms to LEED that he’d in turn purchase and resell at gun shows. He kept no record of the buyers he sold to, nor sought background checks, as licensed dealers must. The resold crime guns then disappeared into the void.

Alloway began to frequent gun shows in 2004 at the latest, prosecutors say, brought by another WestNet officer, then-Shelton cop Troy Wiktorek. Soon Alloway was buying and selling at the weekend gun marts. Prosecutor Miyake says gun-show sales became “an obsession” with Alloway, and his rapid, high-volume dealing caught the eye of undercover ATF agents.

Private gun sellers like Alloway are one of the agency’s focuses, since they supply 80 percent of the weapons used in U.S. gun crimes. High-volume dealers must be authorized sellers—fingerprinted and subjected to background checks. Once licensed, their firearms transactions have to be recorded and open to inspection by the ATF. The seller also has to notify the IRS of his or her ongoing business operation.

Alloway did none of that. He passed himself off as a hobbyist or collector who could sell a gun here and there without a license.

In early 2005, ATF Special Agent Brad Devlin warned both Alloway and Wiktorek they were buying or selling too many guns as unlicensed dealers. Devlin had been able to determine that Alloway alone had bought 54 handguns in just five months, and said he was giving the two cops a warning as a “professional courtesy.” The agent also told Alloway that the ATF was planning to audit LEED’s books, and that his multiple gun deals could be detected, prompting “additional focus” on him.

According to Alloway’s handwritten notes, obtained during the investigation, he took the agent’s advice more as informational than threatening. “Brad will stop any further review at this time,” Alloway wrote in a memo to himself. The agent, Alloway noted, had said a gun purchase of one per week was “OK.”

Nonetheless, Alloway continued to buy and sell at a high rate, obtaining 51 more guns over the next eight months. He tapped into the close-by supply of LEED and other licensed dealers, as well as unlicensed dealers and online gun markets. And he worked his inside game. Prosecutor Miyake says that at times, “custodians observed Alloway walking through the Kitsap evidence room, pointing out guns to Wiktorek and discussing what would be profitable to buy and sell.”

In the fall of 2005, ATF warned Alloway a second time, telling him that if he continued to deal in a high volume of guns, he would have to obtain a license. This time a copy of a warning notice was sent to Bremerton Police and placed in his personnel file. It had no effect. In 2005, Alloway sold at least 140 guns without a license; the next year he would sell at least 158 that the ATF knew of.

Alloway bought himself more time in 2006, when he and Wiktorek opened a storefront gun dealership in Mason County called Renegade Guns and obtained a federal license for the business. As agents would later learn, while Wiktorek followed the law as a federal licensee, Alloway continued to buy and sell off the books.

“In fact,” says prosecutor Miyake, “he used the cover of the Renegade Guns business to further his private selling.” At gun shows, Alloway would rent tables next to Wiktorek to make it appear that both were licensed. But Alloway sold his guns without doing paperwork or requesting background checks, further exploiting the federal government’s patchwork gun regulations.

It wasn’t until November 2010, six months after Alloway had retired after 32 years as a Bremerton and WestNet cop, that ATF agents showed up at Alloway’s secluded home in Port Orchard with a search warrant, seizing 58 firearms.

What took so long? ATF Special Agent Cheryl Bishop says that after Alloway hooked up with Wiktorek, obtaining a firearms license for their business, “it appeared Mr. Alloway had heeded ATF warning letters and was operating within the bounds of the law.” Emily Langlie, spokesperson for U.S. Attorney Durkan, says that in 2010 her office asked ATF to take another look at gun shows because they were a major source of illegal guns. Alloway then reappeared in the ATF’s crosshairs, along with other gun-runners including David Devenny, 70, of Olympia, whose illegal sales included an assault rifle that was later used to kill Seattle police officer Tim Brenton on Halloween 2009 (see “Punishment Capital,” Seattle Weekly, Feb. 20, 2013).

In March 2011, Alloway was indicted with buying and selling more than 700 guns without a license. Going over his business and bank records, the IRS totaled $179,000 in gross gun receipts, from which he’d netted at least $36,000 in a four-year period, failing to pay about $8,700 in taxes.

Though its gun-tracing abilities are limited, the ATF was able to determine that at least two of the guns sold by Alloway had gotten onto the market after having been stolen from their owners. Another eight guns bought and then sold by Alloway had been recovered at crime scenes, including incidents of assaults and illegal firearms possession.

One handgun, a Smith & Wesson .38 bought by Alloway in 2008 and sold on the black market sometime thereafter, was recovered in a 2010 aggravated-assault investigation in Chehalis. The city’s police chief, Glenn Schaffer, says the weapon was one of up to 40 recovered during a warranted search at the home of a man who’d attacked another person with a knife. Officers took all the weapons for “safekeeping,” says Schaffer. But “because none of the firearms were used in the commission of a crime and did not have any evidentiary value in this case, they were all released to a friend of the owner.”

Another of Alloway’s guns, a Ruger pistol, traveled a crime route from one police department to another. It had been confiscated by Camas (Clark County) Police in 2003 and subsequently sold to a licensed dealer. In 2005, Alloway bought the Ruger from the dealer and sold it on the black market sometime afterward. In 2008 it was recovered by Seattle Police after a robbery. According to a May 30, 2008, SPD report, the gun had been used in a U District holdup and carjacking in which a suspect had put the silver Ruger to the head of a man who was robbed of $60 and forced to turn over both his 1999 Mercedes and its title. The Mercedes was later recovered and the suspect arrested.

“It’s really hard to get a sense of how many of these guns ended up in the wrong person’s hands,” says Miyake. “[Alloway] bought and sold on the secondary market, so there’s no way to know what guns were used in a crime.”

Because LEED sold police-confiscated guns that were all entered into the ATF tracking system, the feds were able to get a read on just how big a customer Alloway had become. Altogether during his six most-active years as a gun-runner, Alloway bought 507 weapons from LEED. Seventy-seven of them had initially been seized by either the Kitsap sheriff or WestNet, sold to LEED, then bought and recycled by the detective.

“Alloway,” wrote Miyake in a court memo, “indiscriminately purchased all types of guns, particularly inexpensive guns favored by street criminals, which the business side of him knew would sell quickly.” They included semi-automatic rifles and handguns such the Mac-1- and Mac-11, along with numerous AR-15s. He also sold knives, ammunition, and flak jackets. He “blithely went about selling guns to anyone who would pay him,” Miyake said.

Because of Alloway’s dealings, the Kitsap Sheriff no longer sells its guns to LEED, says spokesperson Scott Wilson. The agency now partners with a Lakewood gun dealer, and has “tweaked” its gun-sales procedures, retaining more weapons for use in training or destroying more if they are of little value. The days of a detective like Alloway roaming the gun room for weapons to peddle are over, says Wilson: “It’s just not gonna happen.”

Nonetheless, police guns still flow into the private market, and even a gun store that limits sales to law enforcement can end up becoming a major supplier of cop guns to phantom buyers. As the Alloway case shows, all it takes is one multitasking rogue cop.

Last February, having pleaded guilty, Alloway went before a federal judge in Tacoma asking to be forgiven. Miyake had asked U.S. District Court Judge Ronald Leighton to lock up Alloway for almost four years. But Alloway’s attorney, Robert Goldsmith, argued that a year of electronic home detention, along with the public shaming Alloway had received from his arrest, was “sufficient but not greater than necessary” punishment.

Numerous friends and fellow officers filed letters of support with the court, seeking leniency. One, Richard McCluskey, praised Alloway’s “integrity” and “high level of qualifications.” Another, Steve Emm, wrote that he has “attended gun shows and I know that 90-plus percent of the vendors at these shows are unlicensed retired people who are buying, selling, and trading guns and accessories as a hobby, just like Roy was doing. They don’t claim income on their taxes any more than people attending swap meets or engaged in frequent yard sales do.”

Alloway’s “mistake of judgment,” his attorney said, “was not rooted in any evil intent, but was an incredibly dumb interpretation of the law.” Alloway stuck to that line when he briefly addressed the judge, according to an account in the News Tribune. “I guess I’d just say that this warning thing [by the ATF agent]—I’m sorry I didn’t understand that better. To me, it asked me to define where I fit. That was probably my mistake, is where I thought I fit.” He apologized for the confusion and sat down.

His daughter, JoAnn Gurney, tearfully asked the judge not to send Alloway to prison because “you’re basically signing his death warrant.” He’d likely be the target of the criminals he’d helped send to the same prison, she explained, from the same courtroom he was now awaiting his own sentence in.

Judge Leighton was unimpressed. Alloway’s career as a cop who sold more than 700 guns without a license “is not a technical violation,” he said to the audience. “It’s a total abdication of his responsibility under the law.” He gave Alloway two years.

Today the ex-cop is halfway through his sentence. Bankruptcy-court papers show that he and his wife—with whom his daughter and her children live—have filed under Chapter 13 to reorganize and repay their debts, amounting to $286,000, with assets of $349,000. Alloway receives retirement pay of about $6,000 a month and owns, among other assets, a $17,000 2011 Harley-Davidson, debt-free.

When he left policing in 2010, he told his hometown paper he was looking forward to spending more time on the things he loves—hunting, fishing, gardening, and guns. “I plan,” he added, “to ride my Harley into the sunset.”

That will have to wait until sometime after January 11, 2014, his current release date. Then again, that’s almost three years earlier than the release of Joshua Dawson, the gun-runner without a badge. E

randerson@seattleweekly.com