John Amory has a sense of humor about his job. You can tell by the mostly sheepish grin that rolls across his face when he’s asked about the particulars of his latest experiment.Inside his small office on the University of Washington Medical Center campus, the 42-year-old “humble general internist” pulls up a video demonstration on his computer and begins a play-by-play. Every scientific study presents a set of challenges that researchers have to think their way around, he says.In this case, it was figuring out how to persuade your average male rabbit to ejaculate into an artificial vagina.A figure appears on Amory’s computer screen. It’s Amory himself, though you’d probably never know it. Like other MDs roaming the halls at UW, he has sensibly cut, slightly graying hair. His pants are often of the slacks variety, and his button-down shirts are mildly rumpled. Onscreen, he’s shown only from the neck down, without a glimpse of his face or any other distinguishing features. Instead, there’s just the anonymous torso and his test subjects: two very large white rabbits.As the video starts, Amory holds a glass receptacle in his protective-gloved hands. Sufficiently aroused by his female counterpart, the male rabbit shuffles toward the front of the cage only to be quite literally cockblocked by Amory’s outstretched arm and the waiting glass beaker he holds in his hand. The trick to fooling the rabbit into actually doing the deed is heating the top cover to 42 degrees Celsius, the exact temperature of a female rabbit’s vagina—a solution born of a lot of trial and error, says Amory.The whole process takes less than a minute. “Hence the phrase ‘quick like a bunny,'” Amory deadpans.Amory is a professor and research fellow at UW’s Center for Research in Reproduction and Contraception. Back in 1977, his boss and mentor, Dr. William Bremner, helped found the Center with a grant from the National Institute of Health (NIH). Three decades on, the University of Washington, through the Center, has become a veritable mecca for researchers interested in the study of the male reproductive system. After 13 years of toiling in the labs in the bowels of the hospital, Amory is now a full-fledged member of a small but international fraternity of researchers who are determined to accomplish something that medical scientists have failed at despite decades of effort: engineering a male birth-control pill.Amory takes sophomoric reactions to his research in stride. He’s heard all the jokes. He works with sperm—feel free to snicker. Afterward, he’ll earnestly recite the manifold reasons why the world’s male population could use another contraceptive option.According to estimates by the U.S Department of Health and Human Services, 40 percent of the three million pregnancies that occur in the U.S. each year are unintended, and 40 percent of those end in abortion. Currently, the world population sits at around 6.5 billion. Most projections predict that number climbing to 8.9 billion by 2050.This is just one of a handful of reasons why, 13 years ago, Amory joined Bremner in the worldwide effort to create an alternative to existing male contraceptive methods: condoms, vasectomies, and withdrawal. “Half of all population growth is through unintended pregnancy,” says Amory, seated in his office at UW. “If you could really get contraception out there that was 100 percent effective, you could pretty well curb those numbers. You could stabilize the populations, and that would in effect help curb energy consumption. And if you’re not expending untold amounts of resources on that, you can actually focus on the alleviation of poverty, and nutrition, the stuff that actually would make people’s lives better.”After nearly 50 years of trying, scientists still haven’t come up with an alternative form of male contraception, as there are a multitude of obstacles to work around. First, there’s biology. The female version of the pill uses estrogen to trick the body into not ovulating. Many other chemical-based male contraceptive methods work in much the same way, using synthetic hormones to prevent the body from producing sperm. But the female pill’s job is easier by comparison: stop the production of a single egg just once each month. Men’s testes produce 1,000 sperm per second, and scientists haven’t developed a pill formulation that can guarantee men the 99.9 percent effectiveness rate boasted by the female version of the pill.”Ask any researcher—you can’t sell men on a contraceptive that is any less effective than the female pill, no matter how convenient it is to take,” says Amory.Then there’s the ebb and flow of interest from the pharmaceutical industry, which, after a free-spending period in the early aughts, has since scaled back its funding of research efforts. As Amory speculates, that decision may have stemmed from the belief that the untold millions it takes to fund this kind of research couldn’t be recouped in the open market.Of course, some people don’t buy the rationale that market forces and scientific limitations are the only reasons a pill hasn’t materialized. As Nelly Oudshoorn notes in The Male Pill: A Biography of a Technology in the Making, feminist health advocates have long complained that the reasons behind the lack of innovation in contraceptive science have more to do with a supposedly predominant belief among men that the responsibility for handling contraception should rightly fall to women.With seed money from pharmaceutical companies scarce, the competition for federal grant money has been ratcheted up a few notches of late. But last year, the National Institute of Health saw enough promise in Amory’s latest pill-form concoction, known as BDADs, to back him with a million-dollar grant.A sketch of the chemical makeup of bis(dichloroacetyl)diamines—or BDADs, as they were christened decades ago—can be found on the dry-erase board on Amory’s office door. Nearly 50 years ago, his grand-mentor and co-founder of the Center, Dr. C. Alvin Paulsen, began working with the compound after scientists discovered upon administering it to mice that BDADs significantly lowered the rodents’ sperm counts. They’d find out later the drug has one significant drawback: When ingested with alcohol, it causes acute nausea. Amory and his team are trying to synthesize a compound with the same contraceptive properties but not the nasty side effect, which he concedes would ruin any dude on the prowl’s chances of getting laid in the first place.”BDADs,” quips Amory. “For when you really don’t want to be a Dad.”But Amory isn’t banking on the fact that the next male contraceptive method to find wide acceptance will be a pill. When it comes to contraceptives, he’s open to all possibilities. Late last year, for instance, the Center put out a call for volunteers to participate in an NIH-funded study to test a gel form of testosterone that, when applied daily to the skin (usually on the chest), prevents the pituitary gland from secreting the hormone that regulates sperm production. (By comparison, Amory’s study on BDADs hasn’t progressed beyond testing on small woodland creatures.) The testing of the gel formulation is cause for excitement, says Amory, as not many studies make it to human trials, so stringent are the safety protocols for testing contraceptives on healthy subjects.In spite of this breakthrough, Amory concedes that the pill formulation may be the most likely candidate to draw Big Pharma back to the field, quoting international studies which show that the most likely consumers of male contraceptives would prefer something they could take orally to injections or implants. And while the University of Washington may be leading the footrace to submit a pill formula to the Food and Drug Administration for approval, testing is still five to 10 years away from reaching fruition, he says—”and I’ve been saying that for the last 10 years.”Outside his office, light from an uncharacteristically clear winter day shines in as the lunch hour hits. Amory grabs a draft of his BDADs study and descends down a stairwell into the building’s poorly lit guts. “Do you want to go and check out the lab?” he asks, smiling like a freshly licensed teen itching to take his new ride for a spin.The bulletin board behind the lab’s oft-locked front door is a monument to contraceptive research, with reports from the BBC and as far away as China on the prospects that a male pill will one day reach consumers, plus published studies from as far away as Australia on alternative contraceptive methods, like implants, that cut off the flow of sperm with the press of a button. When not teaching or seeing patients, this is where Amory can usually be found, poring over data and tracking the progress of the 25 or so enrolled participants in the gel study to determine its efficacy.Inside are a few offices where support staff mind the logistics that keep the Center running, like the latest draft of a proposal to renew the Center’s $9.5 million NIH grant. Those offices are bookended by two sterile-looking waiting rooms and the actual lab space. But it’s in the examination rooms where the proverbial magic happens.After participants in the testosterone-gel study complete the required monthly evaluation, their samples are taken to be examined. Surrounded by high-powered microscopes near the back wall is a lab technician named Isis, who uses both dead reckoning and a specialized computation apparatus called a CASA to determine the number of viable sperm in each sample. The CASA then transmits the data into easily digested tables and images on the connected computer screen.Most male contraceptive research studies, no matter the compound being tested, end with at least 5 percent of participants failing to achieve azoospermia, the medical term for a sperm production rate of zero. Thus far in the gel study, all participants have ceased to produce sperm, a development that Amory sees as promising, though he’s by no means ready to pop a bottle of champagne.Scientific researchers are as dispassionate by nature as by necessity. Their successes arrive in increments, if at all. The delayed return on the invested time and effort would probably drive most people bonkers. But behind the technical jargon, Amory, an admitted history buff, is a reservoir of empathy.”Prior to the French Revolution, people were basically so impoverished that they were deserting their children,” says Amory. “We’re talking hundreds of years before the invention of the condom. And these kids, called ‘foundlings,’ were sent to orphanages and for the most part forgotten. And if you look at the developing world, that’s still happening. If you give people more options, you can affect the environment [and] women’s position in their societies—not to mention curb the thousands of infanticides that take place each year.”Amory is a born mossback. He headed east after graduating from The Lakeside School, completing his undergraduate studies at Harvard with a later stop at the University of California, San Francisco medical school. There his growing interest in the male reproductive system took shape. As a third-year resident at UCSF, he completed a project on the potential of the male contraceptive products being tested at the time to ultimately find their way to market. “We’re still working off the same paradigm, which indicates how far, or how far we haven’t, come since then,” says Amory.In 1997, his wife Josie, herself an M.D., got a job at Swedish Medical Center. Amory was then searching for a hospital with an open resident’s slot when he got a life-changing opportunity.”That’s when I met Bill,” he says.Two years after its 1960 approval by the FDA, over one million American women were taking the first hormone-based contraceptive pill, Enovid. By 1964, over a quarter of American couples were using it, and Pope Paul VI created the Papal Commission on Population, the Family, and Natality to explore the somewhat radical step of changing the Catholic Church’s stance on the use of contraceptives.Yet eight states still had laws on the books that prohibited the use of contraceptive devices, including Enovid. Doctors who prescribed it were often arrested, as were women like Connecticut’s Estelle Griswold, who tried to open birth-control clinics in states with anti-contraceptive laws. In 1965, the U.S. Supreme Court famously ruled those laws unconstitutional in the landmark Griswold v. Connecticut.William (Bill) Bremner, chair of the UW Department of Medicine, can’t remember exactly what he was doing on the day they approved the female birth-control pill. On June 23, 1960, he had just graduated from high school in Lynden, a sleepy little burg located 104 miles north of Seattle and just short of the Canadian border. His family raised cattle, mostly dairy. So when the FDA gave women a way to manage their own fertility, Bremner jokes that he might have been “tending to the livestock.”He didn’t truly become interested in medicine until the latter stage of his undergraduate years. Like Amory, Bremner attended Harvard. Around graduation in 1964, he realized that after years of studying philosophy, he preferred centrifuges to Kant, and decided to head back to Washington for medical school.In 1969, just as Bremner, a fourth-year UW medical student, was trying to decide on a specialty, he met C. Alvin Paulsen. By Bremner’s account a somewhat gruff mentor, Paulsen had for years been studying endocrinology, the study of hormones and the way they control bodily functions like sperm creation.In one highly controversial Cold War–era project, Paulsen, a former student of another renowned endocrinologist, Carl Heller, received a $505,000 grant to test the effect of neutron radiation on sperm production. The study was prompted by an accident at the Hanford nuclear site in 1962 in which three men were exposed to a heavy dose of radiation. Upon examining them, Paulsen found that their ability to generate sperm had been, as he later put it, “altered.”Four years later, he lined up 20 volunteers from the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla, and, with the assistance of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, methodically set about irradiating their testicles. Between 1963 and 1970, 64 inmates were tested to determine why testes were vulnerable to radiation while other human tissue was not. The university eventually shut down the experiment due to liability concerns. In 1996, some of the participating inmates filed a class-action lawsuit against both the state and the University of Washington, alleging that they had not been adequately advised of the risks. Some alleged that in the years following the tests, they had developed health problems, including infertility. The suit was settled in 2000 for $2.4 million.During the 1970s, writes Nelly Oudshoorn, “Scientists working in the area of male reproduction were increasingly confronted with critical questions voiced by feminists about the reasons for the discrepancy between the availability of contraceptives for men and women.” Bremner, with other male members of the medical science community, found himself being taken to task amid increasing publicity about the health hazards posed by Enovid.”If you doubt that there’s been sex discrimination in the development of the pill, try to answer this question: Why isn’t there a pill for men?…It is because women have always had to bear the risks associated with sex and reproduction,” writes Barbara Seaman in The Doctor’s Case Against the Pill, a seminal tome on women’s reproductive health.Sitting at the conference table in his office, Bremner recalls the frustration over the delayed development of a male pill. Around the time he began learning the basics of animal husbandry on his parents’ farm, scientists were discovering that bodybuilders who took injections of testosterone were, for the most part, infertile. But dosing men with an abundance of hormones to inhibit the production of sperm had a number of undesirable side effects—like a nonexistent sex drive. Alternatives were slow to come.”There was this movement where women wanted me to share in the risks, and the responsibilities, of family planning,” Bremner says. “And medical research isn’t always a fast-moving process.”In 1975, two years before he’d help found UW’s Center for Reproductive Research, Bremner co-authored an article in Signs, a popular women’s journal of the time, describing the icy reaction to the apparent lag in the efforts to create an oral contraceptive for men. “Questions about the reasons for this discrepancy are often asked of workers in the area of male contraception,” he wrote. “The questions are on occasion asked with a certain degree of hostility, with the implication that scientists in the area of reproduction research have been responsive to male opinion, which is held to regard the female as the sex responsible for contraception.”Of course, some held an opposite, and no less impassioned, view. In the wake of the creation of the female pill and the 1973 Roe v. Wade ruling, male contraceptives were viewed by some feminists as a “threat to their autonomy,” writes Oudshoorn, who argued that women would never be comfortable relying on someone else for their contraceptive needs.Thirty years later, attitudes have softened. Amanda Wilson, legislative coordinator for the Seattle chapter of the National Organization for Women (NOW), thinks that women would generally welcome additional contraceptive options. But there are caveats.”A lot of women are going to say that the consequence is theirs,” she says. “If the birth control doesn’t work, if the person isn’t responsible about taking it, it’s not the man who gets pregnant. So it’s a very natural response for a woman to say ‘I don’t trust anyone else with responsibility.'”Various studies have been completed to determine whether women do or don’t feel such mistrust, and results have been mixed. The latest to gain worldwide attention was a Teesside University study conducted in 2009, which found women in northeast England to be generally enthusiastic about the prospect of the availability of a male pill. But despite their interest, most of the study’s participants indicated that they wouldn’t trust men to keep to the regimen. Elaine Lissner, founder and director of the Male Contraception Information Project in San Francisco, says this mistrust is partly due to women’s awareness that, despite the obvious motivation to do so, they sometimes fail to keep to the regimen themselves. “It’s human nature to forget,” Lissner says. “That includes women.”Judith Eberhardt, one of the researchers who helped conduct the Teesside study, says it reflects the general perception that men are less diligent than women about maintaining their health, and are therefore less likely to keep track of a pill that, depending on the formulation, might have to be taken daily. “That attitude may be unfair, but it’s well documented that men in the UK seek out medical care far more infrequently than women do,” she says. “But the interesting thing that we found is that it’s a perception that both men and women share. So, to a certain extent, men don’t trust themselves.”A bit of St. Patrick’s Day field research yielded split results. “Using a condom is like eating a piece of candy with the wrapper still on it.” That’s what Joe, a 29-year-old sous chef who asked to be identified with a pseudonym, says when asked if he’d be willing to use a male contraceptive pill if one ever became available. Joe sits on a barstool at 9lb Hammer in Georgetown, grinning. Though wary of possible side effects, he says he’d be willing to take a pill. “I hope that if I’m in a committed relationship, if we choose the male pill, my girlfriend would remind me every day to take it.”Meanwhile, Kevin Earnest, a 23-year-old government worker, says he’d rather wrap it up. “[Take a pill] everyday? That sounds like a lot of work. If I have sex with a girl that I don’t want to have a baby with, I’ll just wear a condom.”By the time Amory began working with Bremner in the mid-’90s, pharmaceutical companies like Germany’s Schering AG and the Netherlands’ Organon had begun to pump millions into male contraceptive research (while U.S.-based companies largely stayed away), including studies conducted at the UW. “Then they suddenly lost interest,” says Bremner.Opinions vary on why exactly that happened. Dr. Ronald Swerdloff, head of contraceptive research at the UCLA Medical Center and partner of the UW in the most recent testosterone-gel study, says that safety is such a concern in the development of medications for people who are not suffering from serious disease that the cost often exceeds the company’s expectations of profit.”It can cost a pharmaceutical company up to a billion dollars to take a product from idea to approval by the FDA,” says Swedloff. “From a financial standpoint in the boardrooms of the large pharmaceutical company, they’d much rather develop medication that could be priced in an area that would allow them to make a significant profit.”Yet in 2002, Schering was so interested in this field that they co-sponsored a worldwide study on the effectiveness of testosterone injections and the Norplant hormone-dispensing implant. The UW, along with several other research centers, participated in the process. But following the study, the Berlin-based pharmaceutical giant Bayer acquired Schering for 17 billion euros and promptly discontinued the program.Denise Rennmann, a spokesperson for the merged company, now called Bayer Schering Pharma, told Chemistry World in June 2007 that the implant, which needed to be changed once a year, and the injections, required every three months, were too complicated. Pharmaceutical companies aren’t usually willing to divulge proprietary information or to speak about the marketing for products that haven’t gotten past the testing phase, but Bayer Schering spokesperson Friederike Lorenzen says that while the project initially showed promise, “the company was not convinced of this inconvenient regimen finding enough market acceptance.”Diana Blithe, head of the NIH branch that funds much of UW’s contraceptive research, says that whenever a project is publicly funded, the government includes a provision that requires the findings to be made public. But discoveries reached inside a private company’s lab go undisclosed unless the company chooses otherwise.”They lock it all up, essentially,” says Blithe. “A bunch of the information and a lot of the products that might have been promising are locked up in a pharmaceutical vault waiting for the company to decide when they are going to return to the field…it’s very frustrating, because you don’t have any leverage to get them to let it out.”Lissner has been following the development of the pill since the ’80s. That companies like Bayer Schering have lost interest in pursuing a male pill isn’t surprising, she says, as the cost-benefit ratio is skewed toward more profitable fields of research.To illustrate her point, she presents a hypothetical scenario: “You can’t go to a shareholder of your company and say ‘OK, we’ve got this product that we can sell in the U.S. Maybe men will take it. Maybe they won’t. But the girlfriends and wives of those that do are going to stop taking the pills that we make. And we’re going to do this instead of develop a drug that we can charge people with cancer, who don’t care about the side effects, a ton of money.’ It’s kind of a no-brainer.”Lorenzen adds that Bayer Schering didn’t think men would abandon condoms and vasectomies, despite studies that point to the contrary. In 2002, the Center for Epidemiology and Health Research in Berlin surveyed 9,000 males on four continents about their willingness to use a male contraceptive, even if it caused some possibly unhappy side effects. More than 55 percent of the respondents answered in the affirmative. A similar study conducted by the University of Edinburgh in 2000 determined that only 2 percent of the 1,894 women surveyed said that they would not trust their male partner to take a contraceptive pill if one became available.Numbers like these give Amory hope. “The thought among the researchers is that we’ll come up with an idea that’s so compelling that we’ll kind of regenerate some new interest from the pharmaceutical companies,” says Amory. “Pharmaceutical companies are fairly maligned in our societies, and there are some researchers that I think unfairly blame them. But they do a lot of innovative research and development; it’s just that their interest isn’t purely scientific, it’s fiduciary. They’re trying to make money, so they’re more likely to abandon something before it reaches the market. But that’s the challenge for us, to come up with something that is good enough to make it through the process.”In the meantime, Amory and his team will continue to plug away. GlaxoSmithKline, the London-based pharmaceutical giant, is interested in BDADs, he says. Yet the question that Amory continually finds himself confronted with is “When?”To which he has a simple answer: “If we knew the answer to that, then it wouldn’t be research.”vcoleman@seattleweekly.comErika Hobart assisted with this report.

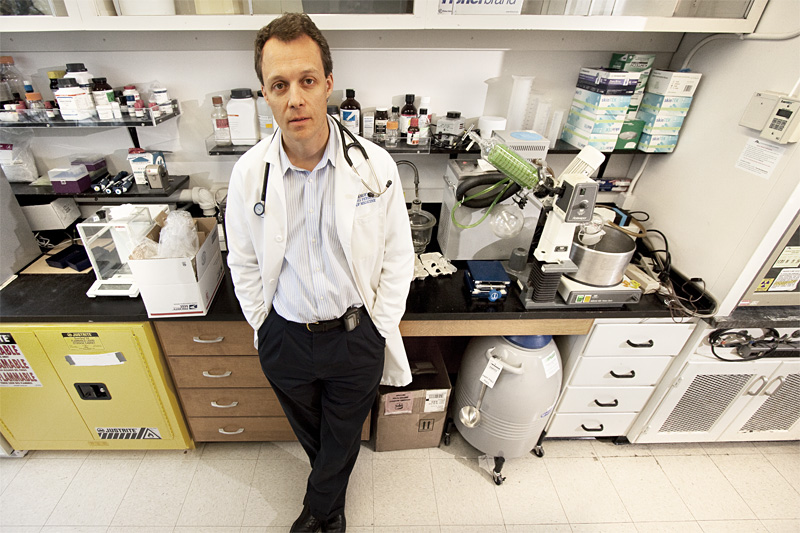

John Amory has a sense of humor about his job. You can