In the Boston Celtics locker room after a November 7 game against the Washington Wizards, Jason Terry is wearing a towel, the tattoos on his chest and arms easy to make out. Under his left bicep is the new one that’s kicked up all the fuss. It’s a sizable rendering of Lucky the Leprechaun, but instead of a basketball, the Celtics icon is spinning on his finger the Larry O’Brien Trophy—the NBA’s ultimate prize.

Premature? Asking for trouble? Well, that’s Terry. On his other bicep is a large tat of the trophy that he got inked before the 2010–11 season, while he was still with the Dallas Mavericks. As promises go, it seemed boneheaded. But then he made it pay off as the Mavs won their first and only championship that year. After a disappointing 2011–12 season, Terry’s free agency took him to the Celtics, and he doubled down on his tattoo caper. It got him a lot of local press, and fans seemed to enjoy how quickly Terry embraced Celtics swagger. But there’s another tattoo that’s even more visible at first glance—the one on the right side of his chest. It depicts the Seattle skyline, along with the words CENTRAL DISTRICT.

That tattoo serves as a reminder that the 35-year-old is a member in good standing of the posse of NBA players from the Seattle area: Jamal Crawford and Nate Robinson (Rainier Beach High School), Martell Webster and Spencer Hawes (Seattle Prep), Isaiah Thomas (Curtis), Marvin Williams (Bremerton), Rodney Stuckey (Kentwood), Brandon Roy and Tony Wroten (Garfield), and Aaron Brooks and Terry (Franklin). There’s even another Puget Sound product in the Celtic locker room—Bellarmine Prep alum Avery Bradley, who is still recovering from shoulder surgery and hasn’t played a game yet this year.

Although Boston’s season has just begun, already fans are palpably worried. Terry has been brought in to replace ex-Sonic Ray Allen, one of the greatest three-point shooters of all time, who left Boston for the Miami Heat, which defeated the Celtics in the Eastern Conference Finals last year before winning the NBA championship. Other new additions have made this a different team, even with stars Kevin Garnett, Paul Pierce, and Rajon Rondo back for another campaign.

In the team’s early games, the squad’s chemistry is poor and Terry rarely touches the ball. As Rondo spins and dives into a crowded lane of defenders, he isn’t finding an open Terry standing by the three-point line. When this is pointed out to a veteran local sportswriter, he cracks, “Why do you think Ray Allen left?”

But tonight, against the hapless Wizards, Boston starts to show some coordination and flash. Terry hits a perfectly arcing three-point shot early in the fourth quarter. Running back on defense, he lowers his upper body, spreads his arms, and fans cheer as he flies like a plane.

After the overtime win, rookie forward Jared Sullinger tells reporters, “We finally de-iced the Jet,” referring to one of Terry’s longtime nicknames.

Though Terry is unarguably one of Seattle’s most successful NBA players, his history with the city—specifically, the University of Washington—is not untarnished. But however diminished his reputation is locally, he’s emerged time and again as one of basketball’s most enduring standouts, with championships at every level. Now he’s chasing another in the most legendary pro-basketball city of them all, a prescribed shot in the arm—or from the arc—for an accomplished but aging Celtics squad whose window of opportunity is about to slam shut.

Andrea Cheatham lives on Mercer Island in a large house which Terry bought her, and she thinks of her third child as her boss. But when Jason was born on September 15, 1977, Cheatham had quite a few bosses.

She was in her junior year at the University of Washington while working a full-time job for the city of Seattle. “We lived in Tacoma, which is like a 45-minute drive to Seattle. So it was quite hectic and Jason was very busy, even as a little boy,” she says. After returning to Tacoma at night, Cheatham worked as a janitor at a couple of different office buildings. “Then I came back to Seattle to work on the weekends as an intake worker at Providence Medical Center,” she says. “I actually worked seven days a week.”

And things weren’t looking good for her son, who was underdeveloped and sickly. Terry’s older brother, Dele, had died after birth, and that worried Cheatham enough that she took Jason to a hospital to have him watched. “They called me by the third day because they couldn’t keep him in his crib. They had a net over it, but he kept climbing out of it,” she says with a laugh.

Terry would be fine, if a bit undersized. (To this day, she says, he’s self-conscious about being so thin, and he wears baggy suits and extra pairs of socks to make himself look larger.) In elementary school, he had a fateful meeting with a P.E. teacher. “I walked into the third grade at Decatur Elementary School and Slick Watts was right there, bald head, headband, dribbling a basketball,” Terry says. “We played basketball every day. That’s why I wear the headband to this day.”

Watts turned out to be more than a sartorial model for Terry: He was also a guy who, like Terry, came on gradually—a player whom nobody really gave much of a chance when he signed on with the SuperSonics in 1973. But two years later he was a starter, and then became a city icon.

“He just wanted to play basketball all the time, and he wanted to take me on,” Watts remembers today. “I’d say, ‘Get out of my face, boy, you can’t handle me.’ And he’d say, ‘Yes I can, Mr. Watts!’ He was always sure of himself.”

Even then, Watts says, Terry was mature beyond his years. “He’s such a grown-up. It’s hard for me to say why that is. But I watched him and he’s so grown up and mature. He’s been a guy we’re all proud of. I don’t take no credit for it.”

Partly, that maturity was forced on him as the young Terry continued to be a sort of missing father for Andrea Cheatham’s growing family. And that’s when tragedy struck.

“It was 1990, and Jason was 13 or 14,” Cheatham remembers. The family was at Wapato Lake in Tacoma, celebrating the high-school graduation of Terry’s older sister. “Two of the kids ended up in the lake. Miguel was 3 and Caleb was 2. I wasn’t more than three feet away from the lake and my back was turned. Then people were yelling, and I saw them working on this infant, and Jason was there. He was frantic. I didn’t think for one minute that it was my child. From there we headed to the hospital. Caleb lived for eight days, and then he passed, which was very traumatic for Jason. By then it already felt like he was the man of the house.”

More trauma was in store for the family. “My oldest grandchild died from an accidental hanging at the age of 9, when Jason was in Dallas,” she says. Her name was Imani Horne and she died in 2006. “You know, kids play around. We don’t really know what happened. It just did.” Today, Terry’s tattoos include the names of “Dele,” “Caleb,” and, for his niece Imani, “Mani Bird.”

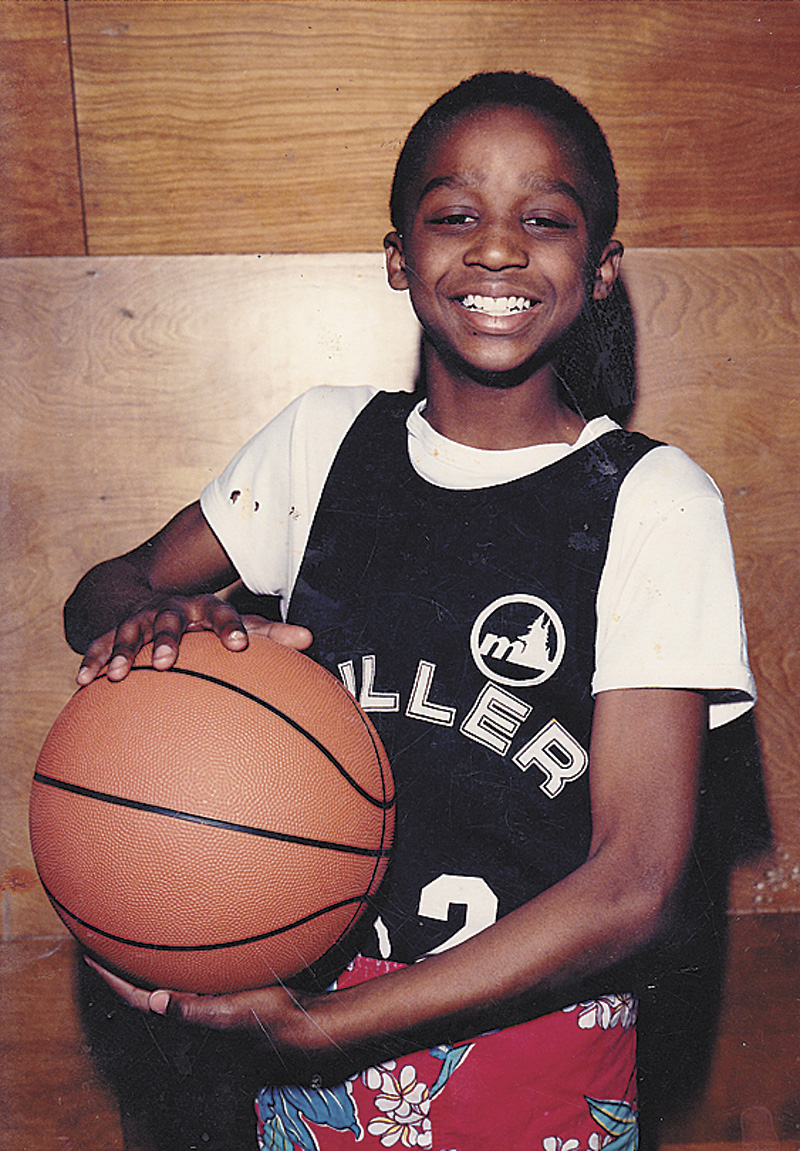

If Terry had to grow up fast, his mother says that her son actually came to organized basketball late, at about 13. “I thought it was just something to keep him busy,” she says. “He wasn’t very good. He was all over the court. He was always laughing and happy.”

In junior high school, Terry faced a setback he never forgot. Recalls Cheatham: “A counselor wrote a letter telling me that he was never going to make it in life because a teacher asked him what he wanted to do, and he said one day he wanted to be a basketball player. You’re never going to make it if that’s your dream, the letter said. He was on the verge of flunking junior high. But after that letter, it just made him even more determined to prove them wrong. And that teacher is one of his staunchest supporters today.”

As he took basketball more seriously, Terry started to bump into another member of the Watts family. “We worked out together almost every day,” says Slick’s son Donald, who is the same age as Terry and competed with him in summer leagues. “It made the rivalry more intense. You didn’t want your boy to get one up on you.”

Donald remembers one trip in particular that brought them closer together, and reinforced where they were from. “We played together in the summertime, and one year we went down to California together for a West Coast All-Stars camp,” he says. “We went down there really fighting for our reputation in Seattle. That was fun. It was an exciting time for us.”

As they developed through their high-school years, they were making reputations for different reasons. Donald, playing for suburban Lake Washington High School, was becoming one of the most effective scorers in the state. But Terry, he says, had a more steady, less flashy style that took longer to get noticed.

“I think he only averaged 13 or 14 points a game in high school,” Donald remembers. “He was young for his age, a late bloomer, a small kid. But he had lightning-quick speed. A lot of other kids had speed, but Jason had a coach in high school who really taught him discipline and defense. Jason was a top recruit because of the leadership he showed.”

Today, Jason Kerr is coach of Franklin High School. But when Terry was competing for Franklin, Kerr was coaching at rival O’Dea, and remembers trying to shake up the young ball-handler. “Because of the way Jason grew up, what he’s so good at—on and off the court—is the ability to code-switch. He can turn into a ruthless competitor on the court, but as soon as it’s over he’s got the biggest smile in the room,” says Kerr. “He had that all the way back in high school. It made him impossible to scout for. He was so mature on the floor, you could never rattle him.”

Asked about Kerr’s observation, Terry smiles. “That comes from being one of 10 [children], you know. My mother was a single parent. I was the second oldest. So I had a lot of personal responsibility to make sure the others had food, to make sure they got to school every day. And for me, basketball was a relief, because I was the leader of my team. I was never, growing up, the best player, or the one that they said, ‘He’s going to make it one day.’ I had to work. And that work came from my mother.”

Even then, he craved the pressure of a big shot in an important game. “That’s another thing coming from my mother. You know, month to month we didn’t know if we were going to have food on the table, if the lights were going to be on or not. I can recall my sixth-grade school year—we moved eight times in one school year within the city limits. Making a shot at the end of the game in front of 30,000 people is nothing compared to moving your kids eight times while trying to make sure food is on the table. That is real-life pressure.”

As her son played on AAU teams and in high school, Andrea Cheatham started to wonder if basketball really could take Terry someplace. “By the time he had won his first championship as a junior, he and I both thought this could be a way he could go to college,” she recalls. “Without financial aid, that wasn’t going to happen.”

After winning the first of two state high-school championships with Franklin in 1994, Terry began to be inundated with calls from college coaches. “I knew he’d be able to get a good scholarship and a degree, but we never once thought it would lead to the NBA. We were just thinking about getting to college,” Cheatham says.

Then her son caught her by surprise. Going into their senior year, Donald Watts and Terry had become the two top basketball prospects in the state, and interest in their choice of colleges was high. It was Terry who first decided that he would stay local and help prop up a struggling Washington Huskies basketball team.

“When he made that commitment, it was pretty simple for me,” Donald says. “We had played together and done some really great things in the AAU in the summertime. I felt that one day we could be the best backcourt in the NCAA.”

Slick arranged a press conference in September 1994 to announce that his son Donald and his former student, Terry, were committing to the Huskies. The two shy, young basketball players visibly cringed as the elder Watts worked the press with his characteristic outspoken style. One reporter noted that Donald could be heard apologizing to Terry for the commotion.

But just a few days later, everything changed.

Cheatham says she was in the hospital, experiencing premature labor during another pregnancy, when she saw Slick Watts on television announce that the two young men had committed to the University of Washington. She was stunned: She had no idea her son had made up his mind.

“He said, ‘Mom, it’s going to work out,’ ” she says. But she was shocked that he had turned down the opportunity to play at the University of Arizona for Lute Olson.

Olson was pretty surprised, too. “Once he had made that commitment to U-Dub, I did as I do with any kid that does that—I sent a letter thanking him for considering us, and wished him the best of luck at Washington and we looked forward to the competition,” Olson says. “Then his mom called me and asked, ‘Did you ever offer Jason a scholarship?’ Of course we did.”

Now that it was clear there was a scholarship waiting for Terry in Tucson, Cheatham talked her son into making a visit.

“She was eight months pregnant! He came down here, he loved it here and the guys he was going to be playing with,” Olson says. “His mom, from the get-go, we hit it off.”

Actually, she was so pregnant that she’d already been hospitalized for premature labor, Cheatham points out. But she went anyway. “Jason realized when he got there that it was a lot better,” she says. They flew back, and within days of their return she gave birth. “We really took a risk,” she laughs.

“It was my mother’s idea to change my commitment and go to the University of Arizona, and I thank her to this day,” Terry says. But in the past, he has expressed some second thoughts. “It’s not that I regret it, but you always think about what-if. The state of [the Huskies] program at that time, you know, I probably would have been a difference-maker. But I don’t know if I would have made the NBA, because when I went to Arizona there was Sean Elliott, Steve Kerr, Damon Stoudamire, Khalid Reeves. These guys would come back in the summer. They’d be competing against us, and that’s what gave us our confidence.”

Donald Watts remembers waiting to hear from Jason after his trip to Tucson, and then learning that he’d changed his mind. Did he remember what he said to Terry?

“Man, I thought we had this.”

Slick admits that he too was disappointed. “I was upset with him for a minute. I wanted him to be a Husky so bad I could taste it,” he says. “I still have a picture over my fireplace, him and Donald and me at the press conference.”

Donald then had to decide what to do. “So now, do I back out? No, I felt Washington was best for me,” he remembers thinking. “I talked to Jason after he made his commitment to Arizona. I said there were no hard feelings about it, and I wished him the best.”

Donald excelled at Washington, which turned around its fortunes after his arrival and went to the NCAA tournament in his junior and senior years. (Today Donald runs basketball camps with Slick, and recently left his position as coach at West Seattle High School.) He’s asked if he remembers whether, when the Arizona Wildcats came to play in Seattle against his team, Terry was booed for his betrayal.

“Booed? Well, I’m in the game, so I don’t really remember that. But I’d be disappointed if my fans had done anything else,” Watts says with a laugh. “It was just a disappointment of not having a player of that caliber in the purple and gold.”

Instead, it was Olson who snagged Terry. “He’s one of my all-time favorites, just like he’s a favorite of anyone who’s ever coached him. He has a great attitude toward everything,” Olson says. “He’s always so positive and upbeat. I remember when I first watched him. It was in a summer BCI league that required if you played one group of five the first quarter, you had to play another five the second quarter. And he was up there waving a towel, encouraging his teammates.”

To illustrate what a team player Terry was, Olson describes what the Wildcats faced at the beginning of the 1996–97 season. Star shooting guard Miles Simon had run into academic trouble the previous year, and was suspended until he could get his grades up. “He couldn’t play in games, but he could work out with us,” recalls Olson. “Then we got him back and he played in a couple of games. JT came in to see me. ‘Coach,’ he says, ‘We’ve got to get Miles back in the starting lineup.’ “

Olson says he explained to Terry why that was going to be a problem. “I couldn’t sit Mike Bibby. That would destroy his confidence. ‘Well, I can sit. I like coming off the bench anyway,’ JT said. And there weren’t too many guys who would take that approach. He was just concerned with helping the team,” Olson says. “I think that’s typical JT. He’s always looking at the big picture, looking at the team, never looking at his own stats.”

“I remember that conversation very vividly,” Terry says today. “And I was having a great year. We were ranked, we had a lot of success, but for the betterment of the team someone was going to have to come off the bench.”

Meanwhile, Cheatham was becoming somewhat legendary for her loyalty to the team. During that sophomore year, when Arizona traveled to a game at Stanford, Cheatham—pregnant with her 10th child—got on a bus with her two youngest children for a 27-hour ride to the game. On the way, the bus driver tried to ditch them at a rest stop, she says. “He didn’t like the baby crying.” After seeing the game, they got right back on a bus for the ride back. “People said I was crazy,” Cheatham says.

She also traveled to Indianapolis that season, as the Wildcats upset three #1 seeds on their way to winning the NCAA championship in Terry’s sophomore year. But even after winning the national championship in 1997, his pro prospects were still uncertain. By his senior year, however, Terry’s qualities were hard to deny. “Coming out of high school, he probably wasn’t someone who people thought would play as long as he has in the NBA,” explains Olson. “He just got better and better every year he was here. And there was no one who deserves his success more than JT does.”

Hall of Fame coach Lenny Wilkens, who had won an NBA championship in Seattle and was now leading a weak Atlanta franchise, took Terry 10th in the 1999 draft.

“Then he had five years of losing in Atlanta. That wasn’t easy for him,” Cheatham says.

What is it about Seattle that has produced such a strong run of NBA talent?

“It rains a lot, so we’re always in the gym,” says Terry. “You go to any gym in Seattle in the summertime, you’ll see 10 to 15 NBA guys and 10 to 15 guys who were this close to making it, and they’re still playing basketball in the city. And it’s competitive. I mean, this is for bragging rights. These are stories you’re going to be telling your grandkids about, these summer games and summer workouts.”

“What I really liked about Seattle players is that they were coachable, and they were really interested in being part of a team,” says Olson. “The pros stick around there in the summer and work out all the time.”

“For me, it was always about who came before me,” adds Terry. “So in my era, a guy like [former Rainier Beach and NBA standout] Doug Christie, he would always come back, he would talk at the camps, at Seattle University. I understood that after I made it, I would come back and do the same thing. I would come back and talk to Jamal Crawford and Martell Webster. Then we’d hold workouts at a local high school, and those guys, the younger guys, would be there watching the older guys work.”

Terry also comes back because he’s still got plenty of family in town. And there’s his foundation. One of its activities: giving away turkeys at Thanksgiving, which he usually misses due to occupational scheduling conflicts. “Last year, there was the lockout. I was able to be there and give out the turkeys and stuff. And to see the community, how it was when I was there and where it is now—we got a long way to go. But the more we can do in the city, it helps,” he says. “But to see some of my old classmates from middle school, you know, coming in and being receptive of the support that I was bringing back, it was good to see.”

Franklin coach Kerr says Terry isn’t looking to score public-relations points when he comes back to Seattle. “He comes into town for four days, and he says, ‘Give me four or five guys,’ ” says Kerr. “He’ll work them out two times a day, eat with them, take them bowling. He’ll give all this time to those four or five guys, and nobody asks him to do it. That’s the kind of guy he’s been.” Kerr says that’s just the Seattle way, adding that “there’s much more of a sense that we’re all in this together for the kids.”

But lately there’s been considerable concern that Seattle’s rich talent pool and strong ties have been threatened by the loss of the SuperSonics. After the 2008 season, the team was moved to Oklahoma City in a slow-motion robbery that had begun two years earlier, when Starbucks chairman Howard Schultz sold the Sonics to Oklahoma businessmen who’d lied when they said they wanted to keep the team where it was. After 41 years and a world championship in Seattle, the Sonics became the Oklahoma City Thunder, who were defeated by Miami in last year’s NBA Finals.

“It’s a huge blow. To not be able to see that level of basketball on the court? It’s weird to have Seattle without an NBA team,” says Donald Watts. “But Chris Hansen is taking care of that.”

In February, Hansen—a Seattle native who is now a Bay Area billionaire hedge-fund manager—started purchasing land south of downtown. He worked out a deal with city and county officials, but, most important, promised to devote $300 million of his own money to the project. Finally Seattle had an arena deal that didn’t involve going to the state legislature for approval, which had sunk previous proposals.

“None of the politicians could shut it down; it had too loud of a constituency. Now the pressure is on the NBA,” says Jason Reid, who directed the documentary Sonicsgate: Requiem for a Team.

At the end of Reid’s film, writer Sherman Alexie bemoans the fact that if Seattle gets a new team, it will just be ripped from some other community that will hate losing its franchise. But Reid says there now seems to be another option: expansion. “As crazy as that would have sounded a couple of years ago, it is a possibility. TV revenue is increasing in the next couple of years. If the Kings don’t come here, or some other team, by 2014, I think expansion will happen.”

And one person pushing for it, he thinks, will be outgoing NBA commissioner David Stern. “Seattle is a big black eye for David Stern. This could be his last act—to order a new team for Seattle.”

After five losing seasons in Atlanta, Terry was traded to the Dallas Mavericks just before the 2004–05 campaign. Despite his personal success with the Hawks—he’d averaged more than 16 points per game—Terry wasn’t coming into an easy situation.

“He probably had just about as tough a job as there is, because he had to replace Steve Nash. And he did it, really, really well,” says ESPN’s Marc Stein. “The Dirk Nowitzki/Jason Terry two-man attack became one of the most feared in the league.”

In only their second season together, Nowitzki and Terry led the team to the NBA Finals, the first trip for the Mavs in franchise history. And what made it even sweeter for Terry was whom he’d be facing: his “Pops,” former Sonic legend Gary Payton, who by that point in his career had landed with the Miami Heat. “I first became aware of Jason when he was a high-school sophomore,” Payton says. “I was seeing a kid who could play very good basketball.”

Payton—whom Seattle traded for Ray Allen, the player Terry is replacing in Boston—was also aware of how much local players idolized him as he led some of the Sonics’ best teams. “They would all come—Jason Terry, Nate Robinson, Jamal Crawford. Jason was the oldest. He was really a baller. I knew he was going to be special. I watched him grow up from an immature kid to a mature adult. When you’re growing up and he’s the oldest guy in the crew, you knew these younger kids were going to be looking up to you.”

By the time he and Terry faced off in the NBA Finals, Payton was at the end of his long career, having joined a Miami team that included Dwyane Wade and Shaquille O’Neal. “It was crazy. We’re always talking. He called me ‘Dad.’ That’s his thing,” Payton says of Terry. “I just told him, on the court we have to be competitors, and we just have to go at it.”

Terry remembers it similarly. “He said that a championship was something he’d been fighting for his whole career, and he wasn’t going to let a friendship stand in the way.”

After taking a two-game lead, the Mavs lost four straight. “At the time, I think that was seen as the worst Finals choke ever,” says ESPN’s Stein. “Because they were really nearly up 3-0. They were up by 13 points in the fourth quarter of the third game. To lose it all from there was as bad a loss as you could have.” And it was Gary Payton’s only shot in the game—with 9.3 seconds left—that broke a 95-95 tie and put the Heat ahead for good.

Terry got another shot at a championship in a rematch with the Heat five years later. But in the 2011 Finals, O’Neal and Payton were gone, and Wade was now joined by LeBron James and Chris Bosh, two stars in their prime.

“We talked on the phone, and I gave him advice,” Payton says. “LeBron went at him, and Jason started making big shots.”

“Jason Terry is a braggadocious kind of guy,” Stein says. “He was giving the other teams billboard material. Dirk would joke about it. During the Finals in 2011, it was one game each, and Terry said something about LeBron being unable to guard him. But then he backed it up.”

Stein says the satisfaction in Dallas was impossible to measure. “Mark Cuban, Dirk Nowitzki, and Jason Terry—they really got the most vengeance with the 2011 Finals victory. They were the three holdouts from the 2006 team that had lost so bad.”

“It was redemption. It was sweet revenge, whatever you want to call it,” says Terry, who scored 27 points in the decisive game. “They beat us on our floor in Game 6 in 2006, and we beat them on their floor in Game 6 in 2011.”

“Terry ended up being with Dirk longer than Nash was. In 2004, nobody saw that coming,” Stein adds. “The biggest problem for him and Dirk was that they had choked so badly in 2006. That was as bad as it could be, but they avenged it in 2011. Once they won that—and against Miami—they’re in the good books in Dallas forever.”

After the championship, there would be no repeat in 2012. “[Mavs owner Mark] Cuban made the decision that he wasn’t going to bring back all the free agents. They let Tyson Chandler go,” Stein points out. Cuban was signing one-year deals with veterans, and with Terry becoming a free agent at the end of the 2012 season, that was probably the best he could get to stay in Dallas, Stein says.

At midnight the moment he became a free agent, Terry says he received a call from Celtics coach Doc Rivers.

“Terry wanted to retire a Mav. He’d said something about his jersey being retired in Dallas,” says Stein. “But Boston offered him a three-year deal with good money”—$15.6 million. “There was no way Dallas was going to offer him more than a one-year deal.”

Terry was visibly angry that Dallas didn’t try to hold on to him. But Stein says he’s gone to another good team, and his legacy in Dallas is already assured.

After the 2011 championship, Terry made his second trip to the White House. In 1997 he’d met President Bill Clinton with the Arizona Wildcats after winning the NCAA tournament. This time he was going to meet Barack Obama.

“I had a few minutes to spend with him, and he knew a story about me that I didn’t think he would know. It was amazing,” Terry says. Obama remembered that in college Terry was known for sleeping in his Wildcats uniform the night before a game. “Just for him to have that dialogue with me, it was something I’ll never forget.” (Today, Terry is known for an even stranger habit: The night before a game, he sleeps in a pair of the opposing team’s shorts. He says he used his contacts to get a pair from every team in the league.)

“But what made it even more special then was my grandmother, who is still living in Tacoma,” Terry adds. “I got a phone call from her—the first call I got when I left the White House. She said, ‘Wow, never in my lifetime would I say that I knew somebody from my family would meet the first black president.’ “

Terry met his wife Johnyika during high school (they attended different institutions). Cheatham offers brief descriptions of her granddaughters, Jason and Johnyika’s offspring: Jasionna (“quiet”), Jalayah (“the Joker”), Jaida (“like her dad”), and Jasa Azuré (“Joker number two”).

After living in Dallas for eight years, Terry moved his family to Boston before the season started. His mother says his house has “eight bedrooms, 10 or 11 bathrooms, sitting rooms, televisions all over the place.”

Cheatham doesn’t speak warmly of Jason’s father, Curtis Terry, explaining that she never had any kind of relationship with him and didn’t want one. But about three years ago, she and Curtis made an effort to be friendly for their son’s sake. Today Curtis lives with Jason’s family outside Boston and helps him run AAU teams.

“It’s kind of chilly. It’s not like Seattle,” Curtis says with a laugh. He likes being close to his son’s family and gets along well with Johnyika. “I used to go to the gym with Jason and shag some balls, but I’m getting older,” he says. Curtis has run AAU teams—Isaiah Thomas was on one of his fifth-grade squads—and helps his son run the girls’ teams that Jason’s daughters play on.

“I like to say I’m a coach at heart, and it’s something that I really look forward to doing after I get done with basketball,” Jason says. “I want to coach at the college level. And this is a good experience for me. I’m coaching girls and they listen to everything I tell them, so it’s a very unique situation. But my AAU program is run out of Dallas; it’s called the Lady Jets. Just being able to spend time with my daughters any way I can is a joy.”

Two nights after the win over the Wizards, the Celtics lose a lackluster game to the visiting Philadelphia 76ers. Although he doesn’t start, Terry is kept in the game for long stretches by coach Doc Rivers. Coming off the bench to rain three-pointers has been the Jet’s calling card for years. After the 2008–09 season in Dallas, he was named the NBA’s Sixth Man of the Year, signifying the league’s most valuable bench player.

After the loss, Rivers is asked whether he’s going to shake up his starting five. “We’ll see, I doubt it, I don’t know. We just finished this game, I’m not thinking about tomorrow,” Rivers replies, sounding irritated. “I will say this, guys: This lineup stuff you guys talk about—it lasts for four minutes, then we switch the lineups. It’s the whole game that matters. I could start everyone on our bench tomorrow. You think it’s going to matter at the end of the game? I mean, really, that’s the way I think. Clearly you guys don’t think that way, but that’s how I think. I don’t think who starts matters. It’s who plays well, who plays the most minutes, and that’s what we’re focused on. I don’t think a guy in our locker room gives a flying crap who starts.”

The next night, Rivers put Terry in the starting lineup.