It’s a secret, of course. But the company whose high-speed computers capture and crunch that phone and online megadata for the National Security Agency is located in downtown Seattle. From its headquarters in the 41-story former Bank of California building, Cray Inc. sells commercial supercomputers that require large buildings to house them and the electricity of a small city to power them. That’s especially true of Cray’s rarely discussed business dark side, its clandestine partnership with the NSA, providing warehouse-sized megacomputers to, among other things, intercept and analyze numbers, times and places of calls and other private data. It’s the classified process that whistleblower Edward Snowden has been revealing in leaks to The Guardian and Washington Post in recent weeks, leaving the White House scrambling to defend the data sweep of American citizens and forcing top security officials to openly discuss the secretive program.

But Cray’s not talking. A corporate spokesperson had no comment this week when asked about the Seattle company’s 36-year history with America’s spy agency. Likewise, there’s little to see at Cray Inc. headquarters – an array of offices behind the doors of Suite 1000 in what is now called the 901 5th Avenue Building. Originally named Cray Research and founded in 1972 by Seymour Cray in Chippewa Falls, Wisc., the company furnished the NSA with its very first supercomputer, ostensibly to break enemy codes. Today, anyone with a phone or internet connection is the potential enemy of Cray’s newest, data-gobbling computers, made at Cray facilities in the Midwest and housed at NSA headquarters in Fort Meade, Maryland, and the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee, where the trapped NSA megadata is processed.

Cray’s press releases detail its sales to commercial customers, including universities, major corporations and governmental agencies. But it doesn’t disclose the NSA work in releases, company profiles or in its online corporate history. And it’s not about to point out its clandestine work to reporters. Just last week, in a Seattle Times story – recounting how Cray had become the No. 2 publicly traded company in the Northwest with sales of $400 million last year – the NSA never came up.

It’s no secret to James Bamford, however. “Cray has made Seattle the spy supercomputer capital,” the bestselling author says on the phone from his home in D.C. He’s been investigating and spilling the secrets of the NSA since his first book, The Puzzle Palace, was published in 1983. In his newest, The Shadow Factory, from four years ago, he was the first to detail the megadata collecting that is making headlines today.

“In terms of what Snowden revealed, it’s nothing really surprising,” says the onetime UC-Berkeley instructor and “Nova” TV-series producer. “And I’ve been writing about the NSA’s access to internet companies for a long time. What is surprising is the variety of information he had access to – and that he was able to obtain legal documents – the Fisa court order, for example.”

In Shadow Factory, Bamford reports that Cray’s relationship with the NSA is much more than government contractor and agency. When Cray Research was bought by Seattle-based Tera Computers in 2000, and became Cray Inc., Tera co-founder and chief scientist Burton Smith – ( since departed for Microsoft) reputedly struck a deal with NSA. “The agency was said to have played a quiet role” in the Cray purchase by Tera “because it wants at least one U.S. company to build state-of-the-art supercomputers with capabilities beyond the needs of most business customers,” Bamford writes. He also cites a document that details how one of Cray’s other little-known spy customers, Australia’s equivalent of the NSA, uses its supercomputers to filter “all telephone conversations, fax calls and data transmissions, including e-mail.”

This massive data digestion is made possible by Cray’s astonishing speeds, having progressed from the 1970s supercomputer limit of 320 million words per second to today’s petaflop speed of a thousand trillion operations per second. Bamford reported on the advacements in a

Wired

piece last year, describing the NSA’s cyber expansion – which includes the $2 billion Utah Data Center, due to open in September, and its $3 billion addition at Fort Meade. Under a NSA contract, Cray has upgraded its Oak Ridge operation to a warehouse-sized supercomputer called the Jaguar. It clocked in at 1.75 petaflops, officially becoming the world’s fastest computer in 2009 (the Chinese this week claimed that title with a supercomputer speed of 33.86 petaflops per second).

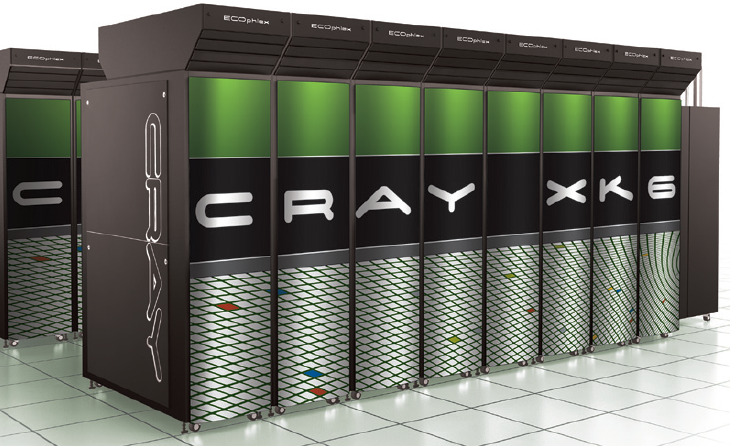

“In the meantime,” Bamford wrote, “Cray is working on the next step for the NSA, funded in part by a $250 million contract with the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency [America’s cybercop]. It’s a massively parallel supercomputer called Cascade, a prototype of which is due at the end of 2012 [but has been delayed]. Its development will run largely in parallel with the unclassified effort for the DOE [Energy] and other partner agencies. That project, due in 2013, will upgrade the Jaguar XT5 into an XK6, codenamed Titan, upping its speed to 10 to 20 petaflops.”

Says Bamford on the phone: “There are two facets to the Oak Ridge operation. One side is the White Side – the civilian side, used by universities and so on. The other is the Black Side, the NSA side of the Cray computers. That’s the side Cray doesn’t talk about.” It is through Oak Ridge and Fort Meade that most data is run, from code breaking to word captures. Though the new Utah site may include a new top-secret Cray computer, the crunching can easily be done at Oak Ridge and elsewhere. The Utah site – one million square feet – is expected to become both a massive electronic storage center and code breaker, aimed at deciphering encrypted financial, business, military, legal and personal communications gathered by the NSA electronic nets around the world, including its large antenna farm on a bluff over Brewster, in Okanogan County.

NSA has also long maintained a listening post at a facility on the Army’s Yakima Firing Range, but it’s closing up that shop, says Bamford.

“Yakima concentrated on satellite communications. That’s history now,” he says. “Cyberspace, and Cray, are the frontier.” From petaflops we’re headed to exaflops – a quintillion operations a second – and zettaflops (a billion trillion), and someday yottaflops [a trillion trillion]. The only secrets left, Bamford says, will be those held in the government’s computers.