It feels awful to even write these words, but Kurt Cobain is better known now for his suicide than for anything else. Even those who know nothing about Nirvana, or music, or Kurt’s personal artistry know he took his own life in April 1994 with a shotgun. He is one of the most famous people to ever commit suicide. Any search for suicide on the Internet immediately yields Kurt’s name near the top, along with Sylvia Plath, Vincent Van Gogh, and Hunter S. Thompson.

Kurt’s suicide made front-page news around the world, made the cover of many magazines (Newsweek ’s headline read “Suicide: Why do people kill themselves?”), was reported on every major television news broadcast, was the subject of round-the-clock coverage on MTV, and was the topic of days of discussions on talk radio. “Kurt became synonymous with suicide,” says therapist Nicole Jon Carroll. For a time his suicide so dominated public thought it “removed him from the brilliance of his artistry,” she says. Carroll would know firsthand: In addition to being a noted therapist, she was Kurt’s sister-in-law.

Kurt’s suicide affected the lives of his family and his fans, but it was not a unique story—except for the fact that he was famous. That same year, in 1994, 30,574 other people killed themselves in the United States. Suicide has become such a public health issue that combating it is now the responsibility of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), as if it were the plague or the Ebola virus. The CDC estimates that for every actual suicide there are 11 unsuccessful attempts, meaning that in the year of Kurt’s death, several hundred thousand Americans tried to take their own lives.

Worldwide, the numbers are in the millions.

Even those closest to Kurt, and who suffered the greatest loss, realized his death was one of many. “It’s not uncommon what happened with Kurt,” Krist Novoselic told me once. “The same story happens all over this country every day. It’s a combination of drug abuse and lack of coping skills.”

The Washington State Youth Suicide Prevention Plan, which was instituted the year after Kurt’s death, identifies the major risk factors for suicide. They read like Kurt’s resume: previous suicide attempt (Kurt made at least half a dozen attempts); past or current psychiatric disorder (like depression); alcohol and/or drug abuse (severe for Kurt); access to firearms (Kurt had many weapons). One other risk factor not on that list, but that experts agree plays a role, is a family history of suicide.

There is much thought in scientific circles that researchers will find a “suicide gene.” A 2002 study published in the academic journal Archives of General Psychiatry found that children whose parents had attempted suicide were six times more likely to attempt suicide themselves. Some of the public discourse on this was reignited in 2009 when Nicholas Hughes, the son of Sylvia Plath and one of her two children in the house when she committed suicide, took his own life at 47.

Kurt’s family history of suicide was significant. Two of his uncles took their own lives, and his great-grandfather committed suicide in front of his family. There was also a family history of depression and alcohol abuse, and many in the field feel there is a strong genetic component to depression and addiction. Researchers continue to look for a suicide gene, but what is known is that certain regions have significantly higher suicide rates.

Social scientists think that when suicide is common in one area, and this greatest of all human taboos is crossed, it gives vulnerable people “permission” when a period of suicidal thought hits.

In Kurt’s case, he had so much suicide in his family and in his hometown, he was already talking about taking his own life as a young teen. Kurt came upon a suicide victim himself when he was in middle school, discovering a man who had hanged himself in a tree. That vision was most certainly indelible in Kurt’s young brain—he extensively talked about it with his childhood friends—and the sheer happenstance of that discovery became yet another horrific part of his history.

I often see things written along the lines of “Kurt Cobain killed himself because of fame.” Maybe. But consider that before Kurt ever picked up a guitar he had seen a suicide victim hanging from a tree, he had family members on both sides of his lineage who had chosen suicide, he had family histories of depression and alcohol abuse, and he grew up in an economically depressed area where unemployment and suicide rates were high. It is possible that before he ever picked up a guitar, he didn’t have a chance. It is possible that fame, rather than taking his life, perhaps gave him more years than he would have had without it. What we do know for certain is that growing up knowing other family members have committed suicide, as was the case for Kurt, increases risk significantly.

The sad story of suicide in our society has continued since Kurt’s death. In the two decades since, suicide rates in the United States have steadily increased, according the CDC. In 2010, 38,354 people committed suicide in the U.S. Thirty-three percent tested positive for alcohol, 23 percent for antidepressants, and 20 percent for opiates. In a given year in America, suicide results in an estimated $34.6 billion in medical costs and work lost. Though young females attempt suicide at a greater rate than men, more men die from suicide since they are more likely to be successful in their attempt—what suicide researchers called the gender paradox. Young men are particularly vulnerable, and according to suicide.org there are four male deaths by suicide for every female suicide death.

Suicide is the second leading cause of death for adults of either gender 27 years of age, after only car accidents. Kurt turned 27 in February 1994.

It truly does happen every day.

Initially, however, Kurt’s widely reported death caused great alarm among public health officials, who feared it was the perfect storm to threaten vulnerable youth. Celebrity suicides have been known to cause copycats, or “suicide clusters.”

When Marilyn Monroe died in 1962, her suicide was extensively studied because she was such a high-profile celebrity with passionate fans. The following month there were two hundred more suicides than usual in the United States. Given Kurt’s large fan base among an age group already at risk, a catastrophe was feared after his death.

Immediately after Kurt’s death, every suicide or suicide attempt in the Seattle area was examined for potential linkages by researchers. One young man did go home after Kurt’s public memorial service and take his own life, and that suicide was widely reported in the press, with speculation that it could be the first of a wave.

There are many websites devoted to Kurt conspiracy theories, suggesting that he did not take his own life; a few of these sites also record copycat suicides. These sites argue that the “crime” of Kurt’s supposed murder is all the more heinous and tragic because it resulted in the deaths of further innocent victims. One of these conspiracy websites lists 19 “Cobain-related sympathetic ‘copycat’ suicides”; another says there are “at least 68.”

Their salacious reports have received widespread media attention.

But what has not gotten as much exposure is the science and detailed statistical analysis by public health experts after Kurt’s suicide. Remarkably, the statistics in King County, where Kurt lived and died, show that the number of suicides actually went down in the months following Kurt’s death.

It wasn’t a huge decrease, but it was significant given generally rising suicide rates. Moreover, the fact that there wasn’t a huge spike was the opposite of what researchers expected, the opposite of what has been reported numerous times in the media, and is in stark conflict to what has been claimed countless times on those conspiracy websites.

Dr. David A. Jobes is a leading suicide expert and the author of one of those studies done after Kurt’s death. He says the figures on the decrease in suicides in the wake of Kurt’s death initially surprised him, but they’ve been confirmed by several further analyses. Another extensive study showed suicides went down significantly right after his death, even in places as far from Seattle as Australia, where Kurt was beloved.

I was in my office when news of Kurt’s suicide came to me with that phone call, but Jobes had perhaps an even more surreal experience learning about it. He was actually attending an international convention of suicide researchers that week; he heard the news sitting in a bar discussing trends in the field when a breaking news report came across the television in the background. “It was the headline story,” Jobes told me, “and I was with a guy from the CDC, and our jaws just dropped. ‘This is going to be bad,’ we said. We thought there was going to be an epidemic.”

Jobes’ extensive study found the opposite occurred. The paper he published speculates several reasons: “The lack of an apparent copycat effect in Seattle may be due to various aspects of the media coverage, the method used in Cobain’s suicide, and the crisis center and community outreach interventions that occurred.” Jobes says another key was outreach by the medical community in the previous year to establish a protocol for suicide coverage, urging media outlets to include suicide resources in their reports. Kurt’s death “was the first time where articles appeared with little boxes that listed hotline numbers, signs of depression, and places to get help,” Jobes said. He says Kurt’s death was something of an “outlier of a celebrity suicide in that it arguably led to reporting that did some good.”

Vicki Wagner, executive director of Seattle’s Youth Suicide Prevention Program, says Kurt’s death still has a role in raising awareness two decades later. “It made young adults, and certainly teens, much more open to talking about suicide, and normalizing it, even if it’s a topic that is never really normalized,” she says. “His death made kids look at the reality of what the impact of your suicide would be.”

In Jobes’ study, his researchers actually went into the homes of people who took their lives after Kurt’s death and searched for Nirvana CDs and posters and examined notes for linkages. Statistically, when a band sells 35 million CDs, their music will likely show up on the shelves of some of those who will take their lives, but Jobes and other researchers looked beyond that. What they found demonstrated that Nirvana fans did not kill themselves simply because of his death. “The results were what we call a ‘proactive non-varietor effect,’ ” Jobes says, meaning that the attention and circumstances of Kurt’s death may have actually encouraged people to seek help: His research concluded that Kurt’s death statistically decreased suicides among Nirvana fans in the period studied.

In some strange way, Kurt dying may have saved lives.

Of all the field notes that Jobes reported in his extensive research, none was more eerie to read about than the case of one young Nirvana fan who did attempt, and succeeded, at taking her own life just a week after Kurt’s death. She had been well aware of resources that the media reported were available, but in her final note to the world she wrote that she couldn’t make use of that help. But she also made a remarkable revelation in her suicide note—she wrote that although she loved Kurt, she was taking her life not because he had, but because of her own issues and depression. “In her note,” Jobes says, “she said she wanted to ‘own’ her own suicide, and didn’t want it linked to his. Some went into this believing an ecological fallacy,” Jobes says—the assumption that people who killed themselves after the death of a celebrity did so because of that news story. In the instance of Kurt Cobain’s suicide, science does not back up that assumption, and in fact the opposite was true.

Exactly why a person chooses suicide is an inexact science. The only subject who can definitively explain his motivation is dead. Still, Jobes speculates several key factors that played a part in minimizing copycats and lowering the suicide rate following Cobain’s. One was Kurt’s chosen method of death, which alone diminished copycats because of the intense violence involved. The thought of pain can halt suicidal impulsivity, and while this may seem counterintuitive, it’s a correlation suicide researchers find often: It’s also why sharp spikes under a bridge can halt suicides at that location.

Though media coverage of Kurt’s death had lurid moments, the fact that Kurt’s method of suicide was widely reported in detail made it less romantic to young fans. The Seattle mayor’s office and governmental offices in other cities also put out press releases that gave contacts for resources, another critical part of the response.

Another key element Jobes cites as a suicide-deterrent factor was Seattle’s public memorial for Kurt. It drew thousands to Seattle Center on Sunday, April 10, 1994, just two days after Kurt’s body was discovered. It was one of the most extraordinary events I’ve ever witnessed.

Immediately after the news of Kurt’s death was disclosed on Friday, fans gathered at the public park that was next to his home in Seattle’s Denny-Blaine neighborhood. I drove there myself when I finally got out of my office that nightmare day.

I saw fans weeping, holding candles, or propping photographs of Kurt against the park benches. As at many of the events that were related to Kurt and grunge, I had dual roles: I was a fan myself, and grieving, but I was also a journalist. Looking at the greenhouse where he’d been discovered, I still couldn’t believe he’d been alive in that room not long ago, but now the whole place was covered in yellow police tape. We would later learn, when the medical examiner determined Kurt most likely died on April 5, that his corpse had lain undiscovered in that greenhouse for three days.

It became obvious that a larger public Seattle memorial needed to happen. The Seattle music community quickly organized a vigil and scheduled it for Sunday the 10th at Seattle Center’s fountain pavilion. Several radio stations helped spread the word and agreed to broadcast it. Though the main purpose was to honor Kurt, there was also some subterfuge in the planning: It was scheduled to run at the same time as the private funeral. There had been some fear that fans would swamp the funeral, which was to be an invitation-only affair. Press were also barred from the funeral, even local press, even newspapers Kurt used to pay $20 to advertise in.

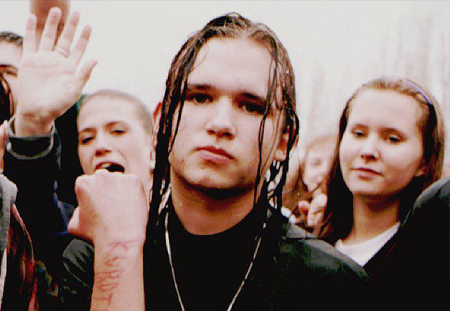

When I walked onto the Seattle Center grounds that Sunday, I expected a crowd, and the 74-acre public park was filled with Nirvana fans. Police estimated 7,000 were in attendance, but there could have been many more, as there were pockets of fans for blocks around Seattle Center, sitting in circles, playing guitar, lighting candles, holding pictures. At the memorial, a small stage platform was set up with speakers, and I went behind it, ran into Marco Collins, and asked him what exactly was going to happen.

“I don’t really know, and I’m one of the organizers,” he said. “A few people will talk, and we are going to play this tape Courtney made.”

Marco said a few words when the event started, and so did a couple of other DJs. Then a short recording by Krist Novoselic was played that urged fans to find their own muse, follow Kurt’s punk-rock ethic, and never forget that “no band is special, no player royalty.” Next was Courtney’s tape. She began by announcing she was recording it in their bed. The crowd was completely silent as she spoke. I have never been in a crowd of 7,000 and had them be that quiet—never.

The recording was so clear you could hear Courtney taking a drag off her cigarette. She said was going to read Kurt’s suicide note. “Some of it is to you,” she said, referring to Kurt’s fans. But before reading it, she asked the crowd to yell “ ‘asshole’ really loud.” And they yelled it. It was kind of a loud communal wail of anger, pain, sadness. Then, for the next 15 minutes, Courtney herself wailed, screamed, and read virtually every line of Kurt’s suicide note.

If the idea for the memorial had begun as a subterfuge to keep the masses away from the nearby private funeral, it turned into the most amazing spectacle of public grief I’ve ever witnessed or been a part of. Not long after her recording was over, when the private funeral ended, Courtney even showed up at Seattle Center. She was holding Kurt’s suicide note. She sat with groups of fans and let them hold and read Kurt’s note.

Shakespeare never wrote such drama for the stage.

But the entire event, more through happenstance than planning, turned into brilliant public health policy. Because Courtney, and the media, specifically addressed how Kurt died, Jobes thinks the public memorial at Seattle Center was the absolute turning point. Courtney spoke very specifically about what Kurt did to himself, which Jobes says took away any glamour that might have been associated with the act and showed how much pain was left for others after his suicide.

“It was really powerful for her to read that note, with all her rage,” Jobes says, “because it punched a hole into the romantic expectation of suicide.” After Love’s recording was played, a suicide-prevention expert talked to the crowd, offering options and information on how to seek help. In the end, Jobes says, “it was a disaster averted.”

music@seattleweekly.com

Here We Are Now: The Lasting Impact of Kurt Cobain (It Books) will be available at booksellers everywhere on Tuesday, March 18. You can order a copy here.