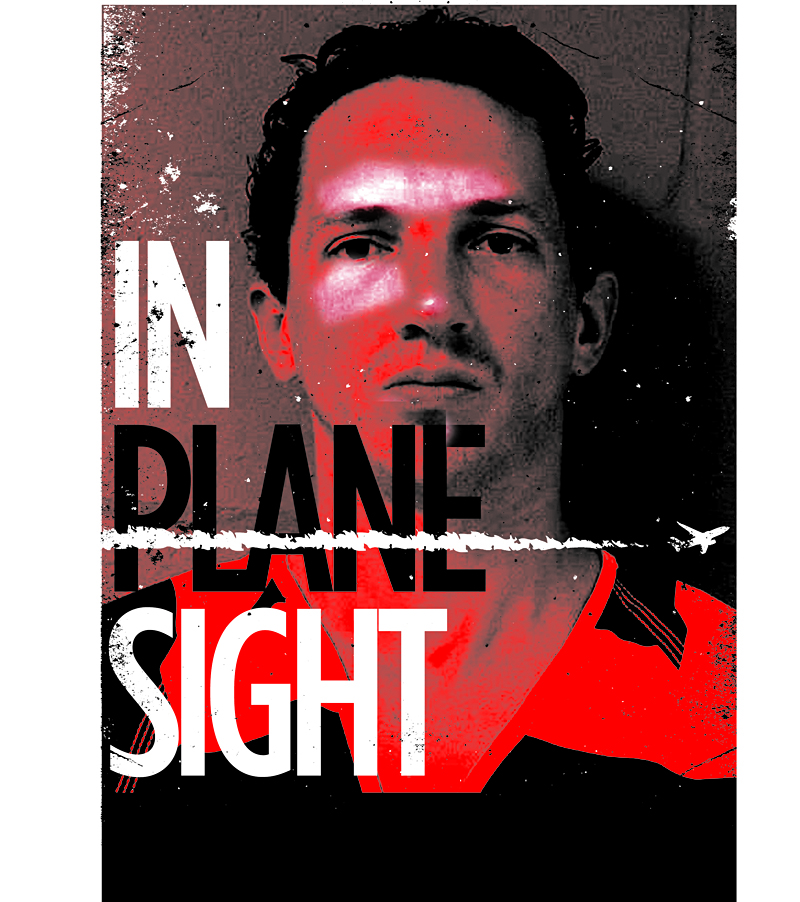

Israel Keyes killed people, but he didn’t have an exact count, he said, sitting at a table in an Alaskan jailhouse, hands folded in the lap of his jumpsuit. A dozen? Keyes couldn’t say for sure. Or wouldn’t. But eight seemed a good number, including four he killed in Washington, where he was raised, served in the Army, and began to murder strangers. Thirty-four years old, uncaring eyes set deep in a stony face, Keyes began to recite his modus operandi as if reading off a checklist from the serial killer’s handbook. Rule #1: Must have multiple personalities.”There is no one who knows me,” he said in a raspy voice, “or who has ever known me, who knows anything about me, really.” Talk with them and you’ll get the he-was-a-nice-quiet-guy answer. “They are going to tell you something that does not line up with anything I tell you because I’m two different people, basically,” he continued. “And the only person who knows about what I’m telling you, the kind of things I’m telling you, is me.”There was the likable, easygoing Keyes, who became an atheist despite—or perhaps because of—being raised in a Bible-thumping home of 10 kids. In adulthood, he grew to be an efficient carpenter and craftsman with a 10-year-old daughter. Then there was the mysterious loner Keyes, who read up on Ted Bundy and became a travelin’ man, making up stories so he could disappear for days and weeks at a time. A sociopath and an alcoholic, he got off on the nightmarish terror he saw in the eyes of his victims. Good Keyes could be funny, Bad Keyes tended toward morbid. Once when he used an ATM, the bank video recorded him wearing a ghastly “Ghostface” mask similar to the one worn by the serial killer of teens in the Scream movie series. It was Bad Keyes’ idea of a joke: The bank card he was using had been stolen from his latest serial victim, a teen girl he’d killed and dismembered.As he sat in the Alaskan jail and reminisced last year, the FBI agent and police officer interviewing him tried not to appear overeager, one of them jotting down occasional notes on a legal pad. They nodded and asked short, encouraging questions as the overhead camera recorded Keyes’ travelogue of killings.Rule #2: Pick your victims at random.”Back when I was smart [before he got caught] . . . I would let them come to me in a remote area,” the slightly built, curly-haired murderer said. “I would go to a remote area that’s not anywhere near where you live, but that other people go to as well.”And if you’re choosing people to kill, he said, you can’t be too picky. “You might not get exactly what you [want].” But on the upside, “there’s also no witnesses, really. There’s nobody else around.” Yet, unlike serial killers who are more likely to terrorize their own communities, Keyes had a signature tactic: He literally went the extra mile to target strangers, traveling hundreds, sometimes thousands of miles—in one case, at least 6,000 miles round-trip—to find his desired targets. He blended into the landscapes of faraway towns, watching potential victims or scoping out neighborhoods for the right house. He especially favored secluded parks, trailheads, and—more Bad Keyes humor—graveyards.As he explained to his jailhouse inquisitors, he saw America as one big killing field. Investigators would later confirm that Keyes racked up tens of thousands of miles over the past 15 years, much of them traveled in search of victims. From just October 2004 to March 2012, he took at least 35 road trips and flights, traveling for weeks on end throughout the continental U.S., Canada, Mexico, and Hawaii.Some trips were made to commit crimes, others for non-lethal pleasures—visiting family members living in the East, Midwest, and South. The builder and handyman helped supplement his jaunts with the proceeds of several U.S. bank robberies along the way, officials say. It was worth the time and money, Keyes told Alaska FBI Special Agent Jolene Goeden and Anchorage Police officer Jeff Bell during the taped jailhouse interviews. Murder, he said, was “a rush.”Goeden could see Keyes was thrilled to recount his bloody adventures. “He enjoyed it. He liked what he was doing,” she would tell reporters after conducting 40 hours of talks with Keyes. Bell agreed. To anyone who would ask why he killed, Keyes would answer: “Why not?”None of Israel Keyes’ family, girlfriends, co-workers, or buddies, officials say, apparently suspected he had been killing and raping strangers and robbing banks from the Olympics to the Adirondacks, from Canada to Mexico, for more than a decade. “Keyes told us he was able to make up excuses why he’d go off for long periods of time,” says Kevin Feldis, an assistant U.S. Attorney in Anchorage. “He did say, though, that it was becoming more difficult to live with others and still commit his long-distance crimes.”But at the start of the century, not even law-enforcement authorities knew there might be a serial killer roaming the U.S. Until he began his jailhouse interviews last year, only Keyes knew of the connection between, for example, the June 9, 2011 abduction, rape, and strangulation of Lorraine Currier, 55, in Vermont, and the Feb. 1, 2012 abduction, rape, and strangulation of 18-year-old barista Samantha Koenig in Alaska. Keyes confessed to both murders, and to killing Currier’s husband Bill.Keyes had been off the radar, living at the northwest tip of the continental U.S. in Neah Bay, staying at his rundown home in the woods near the St. Lawrence River in New York, or taking up residence in Alaska with a girlfriend and his daughter. From Anchorage last year, he continued the murder marathon he’d begun in Washington more than a decade earlier, hopping jets to the lower 48 and setting out on scouting treks in rented cars. For mayhem, it was highly organized. On road trips when he planned crimes, he “went dark,” erasing any electronic trail by turning off his cell phone and using cash instead of credit cards.At various remote locations, he also took the time to strategically hide “Kill Kits,” as officials called them—burying weapons, body-disposal tools, and chemicals for later use. Investigators say he claimed to have buried the kits in half-a-dozen states; they’ve found two so far, in New York and Alaska. One contained a shovel and jugs of Drano.Only Keyes knew of his link to at least five other murders he would briefly sketch out during the months of questioning after his March 13 arrest in Texas last year. He also described at least two bank robberies he cleanly pulled off: one in 2009 in Tupper Lake, New York, and another near Fort Worth, Texas, last February.Officials suspect there were more. Though the heists were thousands of miles and years apart, security-camera videos show him wearing the same striped and padded gloves and holding what appears to be the same silver-and-black semiautomatic handgun at both banks. In other words, he had a pattern.The long-winded Keyes also confessed to the burglary and arson of a home in Texas, and the abduction and rape of a teen Oregon girl in the late 1990s, when Keyes was around 18.Additionally, he said in the interviews, he had been on the verge of committing three other murders last spring. From a sniper’s position at an Alaska park, he had trained his rifle—equipped with a homemade silencer—on a man and a woman when a police officer happened to pull up and chat with them. He then decided to take out the cop as well. But a second officer suddenly appeared, and Keyes backed off. “I almost got myself into a lot of trouble on that one,” he said with a chuckle.The Oregon rape was his first real crime, Keyes said. But now that he was admitting to having murdered or assaulted people most of his adult life, police wondered what he might have done in his youth. Keyes grew up in Colville, a small Stevens County town (population 4,700) about 70 miles north of Spokane. That’s where he got his adolescent jollies, he told investigators, by torturing house pets. That’s also where a 12-year-old disabled girl was killed in 1996, when Keyes was around 17, her prosthetic feet found in a river and her body hidden in the woods. Did Keyes have a role in that? He wasn’t saying.And who were all these other victims he refused to identify? Could he have been the killer of, say, Seattle librarian Mary Cooper and her daughter, Susanna Stodden, shot to death at the Pinnacle Lake trailhead in Snohomish County in 2006? That memorable case occurred while Keyes still lived in Washington, and seems to fit his m.o.On the other hand, investigators also had to weigh whether Keyes was exaggerating his murderous prowess. After all, in that Anchorage jailhouse interview room from April to December last year, he was running the show. Sometimes sipping coffee and nibbling at a bagel, he sat at the head of a long table, offering elaborate testimony on the Koenig and Currier murders, aware that police already had enough evidence to make a conviction likely.But he gave scant details of the four Washington slayings and another on the East Coast, allowing only that he buried that victim’s body somewhere in New York state. He also led investigators to believe there could be at least three more victims beyond the eight he claimed. As he talked, major cold-case investigations were quietly launched in Seattle and elsewhere.”We continue to review all unsolved homicides and many missing-persons cases across the state,” Seattle FBI spokesperson Ayn Dietrich says. “We don’t have an exact number, but it’s in the dozens.”Noting that law-enforcement agencies are involved coast-to-coast, Dietrich adds, “It’s challenging because the victims we know of span such a diverse range of age and circumstances.” The more Keyes talked with investigators, the more inscrutable his crime trail seemed to become.The killer’s strategy of driving or flying extraordinary distances to randomly select a target was adopted by Keyes in part from the m.o. of another Washington serial killer, Ted Bundy. His legendary murder trail stretched from the Northwest to Florida, where Bundy, raised in Tacoma, died in the electric chair at age 42 in 1989.In fact, Keyes’ murder marathon at one point took him to Bundy’s birthplace, Burlington, Vermont, where Keyes ended up abducting and killing Lorraine Currier and husband Bill. Bundy, the self-described “most cold-hearted son-of-a-bitch you will ever meet,” was born there in 1946 to then-21-year-old Louise Cowell at the unwed mother’s home. (She claimed to have been “seduced” by a sailor.)Young Ted Cowell was raised to believe his grandparents were his parents and that mom Louise was his older sister. After marrying Tacoma hospital cook Johnny Bundy in 1951, Louise told him the full story. She defended her son to the end, once telling the Tacoma News Tribune, “Ted Bundy does not go around killing women and little children!” She died last month, at 88, from “a long illness.”As The Burlington Free Press recently reported, Keyes was “stunned” during his jailhouse confessionals when detectives asked him if he knew that Burlington was the notorious killer’s hometown. As it turned out, the paper said, “Keyes had traveled to his idol’s birthplace and didn’t even know it.”Nonetheless, “He knew a lot about Ted Bundy,” said Anchorage police detective Monique Doll at a December news conference. Keyes had studied Bundy and other murderers, although, Doll noted, “he was very careful to say that he had not patterned himself after any other serial killers, that his ideas were his own.”Keyes differed from Bundy in two obvious categories: Keyes covered more ground, and he didn’t wait around for an executioner to finish him off.On the morning of Sunday, December 2, Keyes was found dead by suicide in his Anchorage jail cell, having slit his wrists with a contraband razor blade and hanged himself with a bedsheet. He was a month and five days short of his 35th birthday. He left a note, too bloodied to decipher, officials said, though it’s being analyzed at an FBI lab.Alaskans weren’t exactly saddened to hear that the man they knew as the accused murderer of Samantha Koenig had saved taxpayers the time and money to convict and imprison him. Some wanted him dead from the beginning: When Keyes tried to make a Bundy-like run for it from the courtroom during a hearing last year, the Anchorage Daily News reported that some members of the audience shouted “Kill him!” as guards quickly subdued Keyes.But in the days following his suicide, authorities began to reveal details and release videotapes of his confessions to the murders of Koenig and the Curriers. They also announced he had admitted to killing others, opening a whole new catalog of cold-case slayings. To keep Keyes talking, police had agreed with his request to withhold any disclosures of their findings while the confessions were in progress.They hadn’t solved all his alleged crimes, authorities conceded. But they felt they’d solved the puzzle of Israel Keyes. He “didn’t kidnap and kill people because he was crazy,” Detective Doll said. “He didn’t kidnap and kill people because his deity told him to or because he had a bad childhood. Israel Keyes did this because he got an immense amount of enjoyment out of it, much like an addict gets an immense amount of enjoyment out of drugs.”He took pleasure from recounting his homicidal feats as well, and was not considered a suicide risk, authorities said. So his surprise death was perhaps a final defiant act in a life filled with them, leaving police holding notebooks of tantalizing, half-told tales of murder. “That was a real setback for the investigation of the other cases,” says Seattle FBI spokesperson Dietrich. “It could take years, and then some.”As the accused killer of Koenig, Keyes was charged in federal court with “kidnapping resulting in death,” a capital crime. With the death penalty looming and evidence mounting, Keyes decided to open up.U.S. Attorney Feldis explains how that came about: “We laid out our photos, videos, the ATM records, and other evidence, and explained there was no doubt he’d be convicted [of the Koenig murder]. With his attorney’s approval, he agreed to talk. That’s when he confessed.”But then he didn’t stop with Koenig. Investigators had found news reports on the Vermont double murder stored on Keyes’ home computer, and asked him about it.”He continued to talk, and we became convinced this [Koenig’s murder] was not the first time he had killed someone,” says Feldis. With his attorney, federal public defender Rich Curtner, not present, Keyes chose to open up about the other crimes.Feldis and fellow assistant U.S. Attorney Frank Russo developed what they considered a lawful way to continue the talks. “Keyes wanted to talk to us and did so willingly—that was his choice,” says Feldis. “We read him his Miranda rights each time, and advised he could have an attorney present, and each time he waived that right.”Curtner and Keyes’ two court-appointed Seattle attorneys, Jackie Walsh and Mark Larranaga, did not respond to requests for comment. However, it appears they opposed the continuing talks. In a federal court filing in October, Walsh noted that “the government’s repeated contact with Mr. Keyes” was “interfering with counsels’ ability” to properly defend their client.Facing possible execution, Keyes may have hoped to plea-bargain a life sentence in return for his confessions. Green River killer Gary Ridgway did that in Seattle in 2003. By helping investigators unearth some of his victims’ hidden remains, Ridgway worked a life-without-parole plea deal even though he had killed, officially, 48 women. (He said his body count likely numbered more than 70, but he had lost track).Keyes never asked during the conversations that the death penalty be taken off the table, Feldis says, “although we had not made the decision yet whether to ask for it.”So why was Keyes spilling his secrets?”He had felt increasingly emboldened and invincible over time,” Feldis says. “He committed crimes his whole life, and was never caught. I don’t think he really ever even had close calls. He told us he never planned to be taken alive. He thought he would shoot it out with police in the end.” After being taken down without a shot by a single officer in Texas, he was defeated, and ready to tell his story.He had reigned at least as long as Gary Ridgway. And he outdistanced Ted Bundy, whose 30-murder spree covered seven states between 1974 and 1978, though he, like Ridgway, is thought to have more victims.What worries investigators today is, if Keyes roamed farther and was active longer than Bundy, could he have killed more than his idol?His first murder, Keyes told authorities, was the double slaying of a couple in Washington sometime just after 2001, about the time he left military service at Fort Lewis and settled in Neah Bay, on the Olympic Peninsula. He says he also killed two others in the state, in separate incidents, between 2005 and 2006, but gave no further details.”It is unknown if these victims were residents of Washington or if they were vacationing in Washington but resided in another state,” says Mary Rook, special agent in charge of the Anchorage FBI office. “It is also possible Keyes abducted them from a nearby state and transported them to Washington.”Keyes and his family left Colville in the late 1990s, relocating to an Amish community in Maine. In July 1998, young Keyes, who had recently bought a small, isolated house in Constable, New York, joined the Army and was inducted in New Jersey. He trained at Fort Hood, Texas, then was stationed at Fort Lewis until July 2001, doing a brief tour in Egypt. An Army spokesperson says Spec. Keyes served honorably as an “indirect fire infantryman” capable of manning mortars and handling automatic weapons as well as locating and neutralizing land mines.Details about his post-Army life are still emerging, but Keyes lived and worked as a carpenter and handyman on the Makah Indian Reservation in Neah Bay for most of the next six years. A Makah Tribal Council spokesperson refused to comment, but Tribal Police Chief Charles Irving says that Keyes had been employed as a maintenance worker for the council, handling repair jobs and construction chores.Keyes didn’t stand out as anything other than a likable guy, Irving says. He lived with a woman who bore their child, and he seemed to have kept out of trouble. “He had no run-ins with the police,” said the chief, who noted that the Makah community was taken aback at news of Keyes’ murderous past. “A lot of people were surprised because he was pretty well liked here,” said Irving.Keyes moved to Anchorage in 2007, where he started up a small carpentry/construction business and later moved in with a new girlfriend. His daughter also lived with him part of the time. He left behind no record of serious legal violations in Washington other than a minor traffic stop in Thurston County in 2002 and a drunk-driving bust at Fort Lewis in 2001. For the latter infraction, he did a day at the Federal Detention Center in SeaTac and was fined $375.According to interviews and police and public records as well as his videotaped confessions and investigators’ press conferences, Keyes was the second-born of a Mormon couple on January 7, 1978, in Richmond, Utah, near Salt Lake City. His parents relocated to Colville when he was of preschool age. He was subsequently home-schooled, as were his nine siblings—some given earthy, Biblical names, such as sisters Sunshine, Charity, Hosanna, and Autumnrose.Theirs was a family built around stern religious beliefs, which over the years included Mormon, Amish, and Christian Identity practices. Israel learned early to use his hands, building a log cabin when he was 16, according to a posting last year on his one-man Alaska construction-company website.Family members living in Indiana and Texas did not respond to requests for comment. Kimberly Anderson, the woman who lived with Keyes in Anchorage at the time of his arrest, could not be reached. But prosecutor Feldis says she is not a suspect and had no knowledge of Keyes’ crimes.A recent online newsletter from an Indiana food co-op describes Autumnrose and Hosanna Keyes as “sisters in a large family living in the country near Harlan and Grabill. They have lived all of their lives on a homestead and have taken an interest in various homesteading arts,” including how to make goat-milk soap.Autumnrose Keyes has, however, described the family atmosphere growing up and her struggle with religious teachings in a “Testimony” she wrote in 2011. It was posted on the website of the Church of Wells, a controversial evangelical church in Wells, Texas, which her mother, Heidi, attended. “Around the age of 11 and 12, my heart turned in rebellion toward my parents,” she states. “My two older sisters and I were in a kind of revolt against them. We had friends they did not like, we secretly listened to music they forbade, and we got away with as much as we could . . .”At 13 I fell into grievous sin that my parents did not know about. I began to doubt God’s existence and planned to leave my family as soon as possible and dive head-first into sin. I’ve thanked God many times for my earthly father, who was a strict man. When my sins came to light by God’s mercy, he pulled me away from my circumstances and moved the family to an Amish community.”Things must have looked patched up. After some time, we had a new life, we had friends in the community, and we definitely looked religious. There was less tension with my parents, yet not a closeness or submission. My father passed away when I was 18. I regretted so much my rebellion and the cold distance I’d had toward my father.”She describes a long period of confusion in her attempts to believe in God and seek eternal life. A few years ago, though, she said God “gave me the holy spirit” after she followed His command to be baptized.Israel Keyes, conversely, became a resolute nonbeliever, though he was in apparent agony about it, according to Jacob Gardner, a pastor at the Church of Wells. He says he met Heidi Keyes in Indiana, and she and other family members followed Gardner when he moved to the east Texas church. (Some called the church a cult after the death of a member’s baby last May. The child had been born with life-threatening complications, but members prayed for the 3-day-old to be saved by God rather than call for emergency aid, according to the Cherokee County Sheriff’s Office. No charges were filed.) Gardner describes Israel Keyes as breaking down in tears when family members got into a debate over religion after the wedding of one of the Keyes daughters last February. Gardner, who didn’t respond to requests for comments, posted an audio recording online of a sermon he gave in December describing the event. When one family member asked Israel Keyes when it was that he “chose to hate God,” Keyes began to tremble. “He could not answer,” says Gardner. Others told Keyes they had prayed and wept for his godless soul. One of his sisters—totally unaware of his crimes, the pastor says—told Keyes, “It doesn’t matter what you’ve done, God will forgive you.” The sister was fighting back tears and so was Keyes, who told her, “You don’t know what I’ve done . . . I have to drink every day to forget about it.” Says Gardner: “Finally it got so heated, it was so impassioned, [Israel] broke down weeping in the middle of the reception.” Keyes did, however, attend an area church as a teen in Colville, as did two of his childhood friends and neighbors, young Chevie and Cheyne Kehoe, who went on to become notorious domestic terrorists and white supremacists and are now in prison for murder and attempted murder.According to Bill Morlin of Montgomery, Alabama’s Southern Poverty Law Center, which tracks hate groups in America, the Kehoes and Keyeses were members of a church called The Ark, which preached white supremacy. Pastor Dan Henry confirms the three attended the church (now called Our Place Fellowship) in the 1990s, before the Kehoes turned into terrorists. Chevie, who in 1996 murdered Arkansas gun dealer William Mueller and his wife and small daughter in an attempt to help cover up Timothy McVeigh’s role in the Oklahoma City bombing, was on the run when he was memorably caught on videotape attempting to kill an Ohio state trooper and a sheriff’s deputy in a wild shootout.Morlin, a former reporter for the Spokane Spokesman-Review, quotes Pastor Henry on the law center’s Hatewatch website as saying of Keyes, “I know his family lived here for a time. I don’t remember seeing him here at our church, but he could have been.” However, Henry later told a Spokane TV station that the Kehoe brothers came to the church only once, and that Keyes attended a couple of times but never returned. He said he was turned off by the threesome because they all acted like “hot shots.” His church no longer believes in white supremacy, Henry added. “Our Heavenly Father made every race and he made them because he wanted them. He doesn’t put one above the other.” Though Keyes told Alaska investigators he tortured cats as a kid and had emotional issues, could he have killed 12-year-old Julie Harris of Colville in 1996? A Special Olympics champion with artificial feet, Harris’ body wasn’t found until a month after her March disappearance. Since word emerged in December of Keyes’ serial killings, speculation about his involvement in Harris’ and other murders—including those of Mary Cooper and Susanna Stodden—has helped fill a Facebook page about him. Launched originally to find the then-missing Samantha Koenig, the Facebook site has since been renamed “Have You Ever Met Israel Keyes?” Several posters, including one who lived in Colville, figured the Harris slaying likely set off young Keyes on his long-distance journey to murder. But a spokesperson for the Stevens County Sheriff’s Office says that while a review of the case was made, there’s no apparent connection between Keyes and Harris’ murder. Stevens County Sheriff Kendle Allen also recently told a local reporter that Keyes is not a suspect and that “he was a kid when he lived here.” (News stories from 1996 indicate the person of interest in the killing was actually a boyfriend of the mother’s, who weeks earlier had assaulted the girl’s brother.)The Snohomish County Sheriff’s Office had no comment on any Keyes connection to the 2006 Cooper/Stodden murders at Pinnacle Lake, although the Seattle FBI office indicates the case is among the many that have been or are being reviewed. The murders fit into Keyes’ timeline of being in Washington and bear similarities to his near-shootings of a couple and a cop in an Alaska park. But the slayings do not match the description Keyes gave of his Washington killings. Rather, he told of two separate homicides in that time period. In Eugene, Oregon, detectives do see Keyes as a possible suspect in the 2005 Lane County campground murder of two local educators, Stevan Haugen, 54, and Jeanette Bauman, 56, and their dog. They were shot to death July 1, 2005, while on a camping and fly-fishing trip, the Eugene Register-Guard reports. There were no signs of struggle or sexual assault.Other jurisdictions are reporting that they’ve reviewed cold cases but came up empty. In King County, for example, “We do not have anything that matches,” says King County Sheriff’s spokesperson Cindi West. “I don’t think they had specific enough information to give any agencies anything to really go on. But talking with our detectives, there does not seem to be anything that fits.” East Coast investigators have confirmed, however, that Keyes was the killer of the Curriers in Vermont last June, in a case that shows the lengths to which Keyes was willing to go to leave a cold trail. From Anchorage, he took a plane to Chicago (a gun and a dismantled silencer in his checked baggage), visited family in Indiana, possibly drove to his run-down home on a 10-acre plot in upstate New York, and then motored down to the Burlington area. There he checked into a motel and spent three days looking for his prey, eventually selecting the Curriers. “He was specifically looking for a house that had an attached garage, no car in the driveway, no children, no dog,” Chittenden County State Attorney T. J. Donovan said at a Vermont news conference last month, relaying what Keyes had told Alaska investigators. Keyes was swift and merciless. He cut phone lines outside the house, then broke through a door wearing a headlamp. In a matter of seconds, he confronted the couple in bed at gunpoint, bound them with zip ties, then herded them to their car and drove them to a nearby abandoned farmhouse.He led Bill to the basement and tied him up. Back at the car, Lorraine had almost gotten free, but Keyes tackled her as she started to run, then took her to the house’s second floor. Back in the basement, Bill was yelling for his wife, and Keyes began hitting him with a shovel. When he continued to yell, Keyes shot him to death. Back upstairs, Lorraine likely knew her husband was dead. Keyes then raped her and choked her out during the sex act. Finally, he took her downstairs and strangled her to death.State Attorney Donovan fought back tears as he recounted what he called the couple’s courageous attempts to fight back, and their love for each other. They were complete strangers to Keyes, he noted, and died frightening deaths.Alaska investigators say Keyes willingly told them all about the killing except for one detail: where the Curriers’ bodies might be buried. The land around his Constable, New York, home has been dug up, but authorities found nothing. More than 4,000 miles and seven months later, Keyes killed again. On February 1, 2012, Samantha Koenig was alone in the Common Grounds Coffee shack, set up in an Anchorage gymnasium parking lot, when Keyes walked up around 8 p.m. Wearing a ski mask in the cold night, he ordered an Americano, then flashed a gun. Surveillance tape from inside the shack shows Koenig, known for greeting customers with a big smile, putting up her hands as Keyes’ weapon pokes through the window. He has her turn out the lights, then he crawls in through the service window. He is then seen leading her off toward his truck with her hands bound with plastic ties. At one point she broke free, as Lorraine Currier had in Vermont. But Koenig too was chased and tackled by Keyes. According to an FBI account of events, Keyes drove around town, explaining he was kidnapping her for ransom. Koenig told Keyes her family did not have much money. Keyes said they could ask the public for help in raising it. He promised not to harm her if she cooperated. He sent two text messages from her cell phone, one to her boyfriend, another to the owner of Common Grounds. The messages made it appear Samantha was having a bad day and was leaving town for the weekend. Keyes kept her cell phone, and got her ATM PIN number. He then drove to his home, a house in West Anchorage owned by his girlfriend, isolated on a dirt road. Keyes put Koenig in a shed, tied her up, and turned the radio up so no one would hear if she screamed. He drove to Koenig’s house and got her ATM card from her truck, drove to an ATM, and successfully tested the PIN number. He returned to the shed. Says the FBI report: “Keyes then sexually assaulted Samantha and asphyxiated her. Keyes left her in the shed and then went back inside his house, where he packed for a preplanned cruise that he was taking from New Orleans. He left early that morning [February 2] for the cruise.”While Anchorage officials and Koenig’s family and friends frantically searched for her, handing out flyers and holding a candlelight vigil, Keyes sailed around the Caribbean. He returned more than a week later and used Koenig’s cell phone to pretend she was still alive, sending a text message and demanding $30,000 ransom from her family. The money was deposited in Koenig’s account and Keyes began to withdraw cash, first in Anchorage and later while he traveled south again, from Nevada through Texas. The FBI, watching the account electronically, alerted local authorities each time he withdrew money. But he wore a disguise to fool the bank cameras, and always slipped away before police arrived.Keyes had already broken most of the rules that he claimed to have abided by—not killing locally and leaving no trail. Then came another mistake: At one of the banks, in Arizona, where he had dutifully hidden his face with the Scream mask, the ATM camera recorded the image of his car, a rented white Ford Focus, driving off. An all-points bulletin was issued. A week later, on March 13, a highway patrolman stopped a white Ford Focus for speeding through Lufkin, Texas. After seeing Keyes’ Alaska driver’s license, the officer called for backup. Inside the car, investigators found an evidentiary jackpot: gun, dye-spattered cash from a Texas bank robbery, the Scream mask, and, most critically, Samantha Koenig’s cell phone and Visa debit card. In the following months, during the jailhouse interviews in which he confessed to Koenig’s murder, Keyes couldn’t really explain why he didn’t follow his own crime rules. Investigator Doll had a theory, though: Keyes had become captive to his drug-like compulsion. “In prior cases, he had enough self-control to walk away,” she said. “But with Samantha, he didn’t.” On December 10, the federal case against Israel Keyes was officially dismissed, as the court order notes, “because the defendant is deceased.” But much of the legal story remains untold. The Alaska Dispatch, a feisty online news site in Anchorage operated by former Seattle Weekly writer Tony Hopfinger, is seeking to have the federal files unsealed. “Transparency is essential to public accountability of the criminal-justice system,” Hopfinger says in an affidavit. “Given Mr. Keyes’ self-admitted and wide-roving killing spree, there is unquestionably huge public interest in and fascination with the defendant and the way the investigation and case progressed.” Federal officials last week said they don’t object to at least a partial release of records, leaving it for a judge to decide.Two days before the barista’s murder case was closed, Keyes’ funeral was held in Deer Park, down the road from Colville. His family picked Stevens County for the December 8 ceremony should any of Keyes’ old friends choose to show up. None did. Only his mother, four of his sisters, and three brothers-in-law made up the small gathering of grievers at Lauer Funeral Home. All had flown into Spokane with pastor Jake Gardner, the only one who would speak with reporters. He made it clear that Keyes had earned no one’s forgiveness.”Israel rejected the gospel and thus the outcome of his life is this tragic story,” said Gardner, standing outside in the snow. “He’s not in a better place. We believe that he’s in a place of eternal torment.”Gardner said Keyes would be buried later. The pastor would not say where. It seemed poetic justice. Much like Keyes hid the bodies of his victims, his family would hide his.randerson@seattleweekly.com

Israel Keyes killed people, but he didn’t have an exact count, he