In hindsight, the last night of Edwin Hutton’s life was littered with bad omens. A 54-year-old cook at a bar on Capitol Hill, Hutton was set to clock out at midnight when he accidentally locked his keys in the back room. Then he discovered a flat on his ’56 Plymouth Sedan.

After replacing the tire and picking up a spare key from a co-worker, Hutton bellied up to a dive across the street from his own bar that was called, as fate would have it, the Lucky Inn. It was just past 1:30 on Saturday morning, December 4, 1965.

Hutton asked the bartender, his friend Ken Klepeck, to cash his $30 paycheck and mix him a screwdriver. He gulped it down, then ordered another.

About five minutes after 2 a.m., Klepeck cleared out the bar and began counting the cash in his till. From where he stood, he could see out the window to the intersection of 14th Avenue and East Madison Street, where he watched as Hutton walked unsteadily to his car, followed closely by two men who had been loitering on the corner.

Klepeck would later tell police that the men were “two Negroes:” one tall and thin, the other short, stocky, and wearing a sport coat. He said he had noticed them earlier in the evening because he feared they were casing his place for a robbery. So when he saw the men climb into the front seat of his friend’s Plymouth, Klepeck stuck his head out the front door and shouted to Hutton, asking if everything was all right. Hutton rolled down his window, hollered “Hell yes! They’re a couple friends of mine,” then drove off.

In truth, Hutton had never met the two strangers now in his car. Near Garfield High School, they directed him to turn onto a side street. At the intersection of 22nd Avenue and East Terrace Street, they told him to stop. The shorter of the two men pulled out a .32 caliber pistol and pointed it at Hutton’s head. His partner got out, walked around to the driver’s-side door, and demanded Hutton’s wallet.

A little tipsy and carrying almost a full paycheck’s worth of cash, Hutton lashed out at the man with the gun, hitting him in the face and shouting, “Nobody’s going to take my money!”

The pistol went off twice during the ensuing scuffle. The first shot was fired from such close range that when the gun recoiled, the barrel sights left a mark on the bottom of Hutton’s chin. That bullet hit him in the throat, grazing his jugular vein before lodging behind a vertebra in the back of his neck. The second slug came to rest underneath the skin near his left shoulder blade.

By the time police arrived, Hutton was lying face down in the wet gutter next to his car, barely alive. Pressed for details about his assailants, he could only offer the limited description provided by his buddy Klepeck: They were “a couple Negroes,” he said. Later, in the hospital, Hutton gave detectives a few more clues. He said one of the men was taller and wore a dark dress hat. The other was husky and about 5 feet 9 inches tall, with a small scar on his forehead. He didn’t catch either of their names.

Conflicting accounts from the few eyewitnesses at the crime scene weren’t much help either. One said they’d seen two men run away into the night; another swore a car parked next to Hutton’s sped off just after the shooting. The person who got the best look, a 17-year-old car thief named William Estill, said he had been standing in a nearby alley when the shots were fired. He told police he’d seen two men running, but, like the others, couldn’t get a good look at them.

Soaking wet and bleeding heavily, Hutton rambled to police as he waited for an ambulance. A detective would later testify that the cook went from quiet and afraid to cursing his attackers and vowing revenge. Yet Hutton would never get his shot at payback: He died the following afternoon.

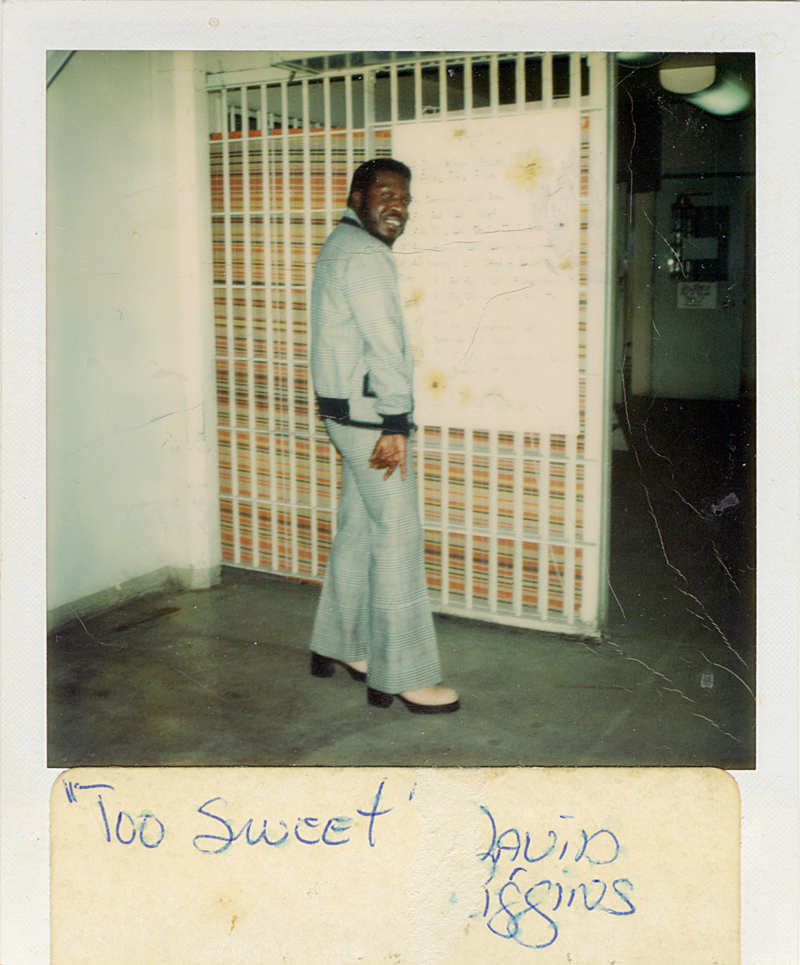

When they came to get him, Dawud Malik was dozing under a tree on a sunny spring Seattle afternoon. It was May 27, 1966, nearly six months after Edwin Hutton had been shot, and Malik, 19, was then going by his given name, David Washington Riggins.

Malik was stretched out on the front lawn of the Riggins family’s Central District home, taking advantage of the good weather along with his girlfriend and brother James. The only thing on his mind before he closed his eyes was what to do first before a Friday night out on the town: pick up his dry cleaning or take a bath?

“It was a gorgeous day,” says Malik from behind a glass barrier at the Stafford Creek Correctional Facility in Aberdeen. “I didn’t have a care in the world.”

But his peaceful slumber was soon interrupted by four Seattle police officers. They searched his house—without a warrant, he says—and took particular interest in his new watch and cigarette lighter. Malik knew the goods were stolen, but he wasn’t concerned. In and out of juvenile lockup since he was 15, he had grown accustomed to police questioning.

It wasn’t that Malik came from a broken home. On the contrary—his father, T.Z. Riggins Sr., was a pastor at New Hope Baptist Church. He had seven brothers and five sisters, and he and the other Riggins boys were known both for their knowledge of scripture—which T.Z. demanded they recite each morning before school—and for being fiercely competitive athletes.

Long before he became chairman of the King County Council, Larry Gossett was a Central District kid who played basketball and flag football with Malik at the local community center. “He and his older brothers were tough,” says Gossett. “He was aggressive, but he was always a good teammate. He’d take up for less assertive, mild-mannered kids on his team. He was never a bully.”

Off the playing field, however, Malik was trouble. He got caught shoplifting, and was absent from Franklin High School so often that a judge sentenced him to eight months at a juvenile detention center, where his new classmates tutored him on the finer points of petty crime.

Now 64, with wire-frame glasses perched atop a broad, flat nose, Malik chuckles when he recalls his misspent youth. “I learned how to hot-wire a car, but I didn’t know how to drive,” he says.

Once back at Franklin, he found someone who could steer and work a pedal. Malik was eventually caught stealing a car and sent back to juvie. This time, he didn’t return to high school. At age 19, he got a job at the Lockheed Shipbuilding and Construction Company as a laborer, sandblasting and scrubbing the hulls of tankers. He’d been there only a few days when the cops came calling.

When the cuffs went on, Malik says, the police told him he was being arrested for third-degree assault. His older brother James watched as Malik was led to the backseat of a waiting squad car. Now 76, James says that unlike Malik, he was worried. He warned him to “get serious.” But when his kid brother turned around, he was anything but.

“Don’t worry,” James says Malik told him. “I just did some burglaries. I’ll be out by Saturday.”

Nine days after the murder of Edwin Hutton, an informant gave police the break they’d been looking for. He said the shooter was Floyd Bell Brown. Not only did Brown fit Hutton’s deathbed description of his killer, he had purportedly boasted that he and a friend had “hitched a ride with a man, directed him to 22nd and Terrace, and rolled him.”

Brown, however, was nowhere to be found. And police would soon be given good reason to stop looking for him. On May 25, 1966, they arrested Leodis Smith, a lanky, dark-skinned man who, at 6 feet 3 inches, fit Hutton’s description of his taller assailant. What’s more, Smith was also the prime suspect in three brutally violent Central District home invasions that had occurred earlier that month.

On May 20, Smith and another man followed 65-year-old Earl Ohlinger to the front door of his First Hill apartment. When Ohlinger tried to close the door, Smith and his partner barged in behind him, shoved him onto his bed, and smothered his face in a pillow while they searched his pockets. Knocked cold by a hammer blow to the back of the head, Ohlinger awoke later to find he was missing $28, a watch, and a cigarette lighter.

Two nights later, Smith and another man broke into the home of Dennis Hagan, a worker at a candy factory. When Hagan returned from the movies with his 10-year-old son Phillip, Smith pounced. He grabbed the elder Hagan by the throat and threw him to the ground, where Smith’s partner used the blunt end of a hatchet to knock him out. Then they put Phillip in a closet while they ransacked the house. Unhappy with their haul of only a few dollars in loose change and a box of old jewelry, Smith beat Hagan with the butt of a shotgun while his accomplice choked Phillip with a length of rope until the boy passed out. Then Smith turned the shotgun on the child, bludgeoning him with the butt of the weapon until the wood split in two.

Three days later, on May 25, Smith committed his third and final crime. He and a partner targeted a home owned by an elderly couple named Simon and Reva Krimsky, ages 85 and 66. At around 3:45 a.m., Smith and the other man forced their way through the Krimskys’ front door. Woken by the commotion, Reva let out a scream before being strangled to death by Smith, who used a necktie Simon had left laying in the living room. When Simon emerged from the bedroom, Smith and his partner told the old man to lie down next to his wife. When he tried to raise his head to see what was going on, the shorter of the two men kicked him.

The burglars left the Krimsky home half an hour later with only $9 and two wristwatches. Simon then called police from a neighbor’s house and gave them a description of his wife’s killer. Smith was arrested later that night. It was then that he first mentioned his friend Malik.

Although they’d grown up not far from each other, Malik says he and Smith didn’t meet until both were in their late teens, when he broke up a fight at a nightclub in which Smith was on the losing end. Smith told police it was Malik who had given him a ride to the area where the Krimskys lived.

Though more than half a year separated Hutton’s murder from the home-invasion robberies, Smith and Malik fit the description of the “two Negroes,” one tall and thin, the other short and stocky. And when detectives ran their fingerprints, Smith’s matched those taken from a pair of sunglasses found on the floor of Hutton’s Plymouth.

New evidence in hand, detectives went back for another interview with Klepeck, the Lucky Inn bartender. This time he told a slightly different story. Not only did he say he had poked his head out of the bar’s front door to check on Hutton, Klepeck now claimed he also had walked outside and down the block, so that he was standing just across the street when the men got into Hutton’s car. After studying a half-dozen mug shots, Klepeck told police that Malik was definitely the short guy he had seen leaving with his friend that night.

Ohlinger, Krimsky, and the Hagans also viewed mug shots and police lineups, eventually identifying Smith and Malik as the men who had attacked them. Meanwhile, the physical evidence against Smith continued to mount; his fingerprints also matched a set police had lifted from a mirror in Ohlinger’s apartment.

The case against Malik wasn’t as strong, but in addition to positive IDs from victims, the cops found Malik carrying Ohlinger’s missing watch and cigarette lighter the day he was arrested. It was more than enough evidence for David Soukup, a King County deputy prosecutor at the time, to press seven felony charges against both Smith and Malik, including two counts of first-degree murder.

By the time their trial began that September, the city was still cooling off from a heated boycott of the public schools the previous spring. Race relations in mid-’60s Seattle were already fraught with tension. The news that two young black men had allegedly robbed, assaulted, and murdered a series of white victims living in the city’s largest African-American neighborhood did nothing to improve them.

All 12 of Smith and Malik’s jurors were white. And one of Judge Francis Walters-kirchen’s first orders—for the bailiff to censor the jury’s newspapers so they couldn’t read about race riots in San Francisco—reflected the chaos roiling outside the relatively calm courthouse corridors.

Malik and Smith were tried jointly, and the judge gave specific instructions that further entwined their fates: The jury was to consider evidence in one crime as indication of guilt in the others. It was a decision that would prove devastating to Malik’s case.

Confessing to his attorney, Robert Egger, Malik admitted that he was with Smith the night of the Hagan robbery. He had choked Phillip and watched as the 10-year-old was beaten. He wanted to plead guilty. But Egger, perhaps fearing that such a plea could be used against Malik on the other charges, shot down the idea.

During the trial, Phillip Hagan took the stand and testified that Malik was the man who had attacked him and his father. Egger tried in vain to persuade Walterskirchen to declare a mistrial. He felt that the boy’s testimony would undoubtedly convince jurors that Malik had committed the more serious offenses. “There is no way in the world that we can avoid the prejudice of this last case being inflicted into the two murder cases,” said Egger. “I don’t think they can have a fair trial under these circumstances.”

The judge was unmoved. And what’s more, he allowed prosecutors to suppress several key pieces of evidence, including the police report that contained Klepeck’s original statements about the night of the Hutton murder. Klepeck was the only witness who put Malik inside Hutton’s car. Walterskirchen’s decision meant the jury would never hear about the inconsistencies in his story.

Nor did the court hear Malik’s alibi for the Ohlinger robbery. Malik told Egger he had been at a friend’s house that night, gambling and playing cards downstairs with the men while the women were in the living room upstairs holding a baby shower. Egger balked, telling Malik that he didn’t want to give the jury any more reason to question his character.

“He said, ‘We don’t want to say that and give the impression it was a house of ill repute,’ ” recalls Malik. “He said, ‘We don’t need ’em. We got ’em beat. We don’t need to call them.’ “

Instead, the jury listened as James Riggins offered testimony that may have been even more damaging to his younger brother’s character. James said that he had been with Malik at a restaurant when he bought Ohlinger’s watch and cigarette lighter from a street hustler for $10.

“I knew it was hot,” says Malik. “The dude told me it was hot. But back then it wasn’t whether or not it was hot, it was the price.”

On the witness stand, Ohlinger admitted that he had wrongly identified mug shots of two other men before settling on Malik. Krimsky also confessed that he looked at “lots of pictures,” but never saw one that looked exactly like the short, young black man who had attacked him. As for the police lineup, Krimsky said, “one from the two [that the police showed me] was in my place.”

When Egger pushed Krimsky, asking if his client was that man, the old man waffled. “I think so,” he said.

But while the victims expressed doubts, the jury did not. On October 6, 1966, after deliberating for a day and a half, they found Malik and Smith guilty on all seven counts and recommended a penalty of death by hanging.

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer noted at the time that Smith “sat stone-faced” when the verdict was read. “The only show of emotion was given by Riggins,” the newspaper reported, “who abruptly threw an empty paper cup on the defendants’ table. His mother and teenage sister broke into tears. Women jurors too appeared close to tears.”

On the morning of April 4, 1968, Malik was awaiting sentencing at the King County Jail when a guard escorted a familiar face into the cell across from his: Larry Gossett, his old friend from the Central District. Malik was puzzled. Whereas he was a high-school dropout, Gossett had gone on to become a leader of the Black Student Union at the University of Washington.

“Damn, Larry,” said Malik. “What you doing in here?”

Gossett explained that he and seven other students had been arrested for organizing a nonviolent protest at Franklin High School, after the principal had suspended two black female students who dared to wear their curly hair naturally.

Later that afternoon, while Gossett and Malik were catching up, word reached the prisoners that Martin Luther King Jr. had just been assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee. “The blacks in jail wanted to beat up the white prisoners,” says Gossett. “We said, ‘No, man, that’s not how you pay respect to brother King. He’d be concerned about everyone in this jail, because we’re all dispossessed.’ “

According to Gossett, he and his fellow college students were having a hard time convincing the angry inmates to back down. So he turned to his old friend. “Strategically, I enlisted Dawud, who’d been in the jail for over a year,” says Gossett. “He helped cool those guys out.”

But while externally Malik could impart enough calm to quell a potential jail riot, internally his blood still boiled at the thought of being wrongfully convicted. “I was full of anger and disappointment,” he says. “I was bitter, and it was killing me from the inside.”

The following year, Malik was transferred to death row at the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla. It was there, he says, that he finally found himself. “I started asking myself questions—who I am and what I wanted to be,” he says. “That’s when the light came on: You’ve got to look at it another way. I remember asking myself, ‘When was the last time you thought about taking something from someone?’ It’d been so long. That’s when I knew I changed. I realized I no longer thought like that.”

Though raised by a preacher, Malik says he didn’t become spiritual until his time in prison. He tried Catholicism and Buddhism, but says that “When I found true Islam, I found peace. I realized the connection we have as human beings.”

He converted in 1978, changing his name from Riggins to Malik, meaning “King.” Along with his spiritual awakening came a passion for learning. He earned a high-school diploma, then his bachelor’s degree in sociology. He became a voracious reader, devouring the works of W.E.B. Du Bois, James Baldwin, Richard Wright, Alex Haley, and others, “the types of books that made you do a lot of soul-searching and question things greater than you,” he says.

Malik’s transformation was so profound it even caught the eye of B.J. Ray, Walla Walla’s warden. Impressed by the changes in his prisoner, Ray remarked in a 1976 letter that “if there is such a thing as rehabilitation, [Malik] surely is such a person.”

Despite having admitted to his role in the robbery and assault of the Hagans, Malik has maintained from the moment he was arrested that he had nothing to with the other crimes committed by Smith. And the more educated he became during his imprisonment, the harder he fought to prove his innocence.

In 1977, Malik reached out to Smith and asked him to compose a sworn statement declaring that he was not Smith’s partner in crime. Smith went on to author three affidavits, eventually declaring that his accomplice was actually a man named Charles Daniel. In 1995, Smith wrote that Daniel was a dark-skinned black man with an athletic build and a light mustache who also lived in the Central District.

“In contrast to me, Charles Daniel was much shorter,” wrote Smith. “Because of Charles’ size and build, Dawud would be mistaken for Charles.”

Smith, currently serving a life sentence at the Clallam Bay Corrections Center, believes that Daniel died in Vietnam. But documents obtained last month by Malik’s attorney reveal that Daniel actually died on October 1, 1969, in a botched gas-station robbery. According to a death certificate from the King County Coroner’s Office, Daniel was six feet tall and weighed 130 pounds. Police records indicate that Daniel had a lengthy criminal record that included armed robberies.

Malik also eventually contacted the friends who had been gambling with him the night of the Ohlinger robbery. Though they admitted they could have provided him with an airtight alibi, they told Malik that they’d never received so much as a phone call from his attorney Egger. And Egger, who died in 1995, eventually had legal problems of his own; he spent 20 months in prison after being caught in possession of money stolen from a bank.

In 1996, 30 years after his arrest and conviction, the state’s Board of Clemency and Pardons agreed to hear Malik’s case. The board voted 3-2 in his favor. Nearing the end of his term, then-Governor Mike Lowry deferred the ruling to his successor, Gary Locke, a former King County deputy prosecutor, who ignored the board’s recommendation and denied clemency.

Malik was disappointed, but didn’t lose hope. “I just took it in stride,” he says.

Then two years later, one of Malik’s former attorneys obtained what Malik thought would be the key piece of forensic evidence that would lead to his exoneration. Through a request under the Freedom of Information Act, he received an FBI report dated June 20, 1966 that contained “a microscopic analysis” of soil found on his shoes the day he was arrested.

The Krimsky intruders had left footprints, and Seattle police had asked the FBI to determine if the dirt on Malik’s shoes was the same as the soil in the couple’s flower bed. The results were negative, as was a test to see if the shoes had fibers or hairs from the crime scene.

The report—which was never mentioned during the original trial—did not have the impact Malik had hoped for. In 1999, the Washington State Supreme Court denied his request for a new trial, writing that Simon Krimsky’s eyewitness identification was stronger than the new evidence. Subsequent appeals also were denied.

By the time the Clemency and Pardons Board agreed to hear Malik’s case for a second time in 2003, he had assembled an impressive coalition of supporters. Among them were clergymen, prison volunteers, councilman Gossett, former Seattle NAACP president Carl Mack, and University of Washington law professor Jackie McMurtrie, the founder of Innocence Project Northwest, an organization that works to exonerate wrongfully convicted prisoners.

Malik was one of the first inmates to contact McMurtrie and ask for help after she created the Innocence Project in 1997. Since then, the organization has exonerated 15 prisoners in Washington, sometimes by utilizing DNA evidence unavailable during the original investigations. McMurtrie believes that Malik’s conviction, while lacking a DNA silver bullet, is suspect because police and prosecutors relied on questionable eyewitness identification. Nationwide, DNA testing has been used to overturn more than 220 wrongful convictions, and more than 75 percent of those cases involved eyewitness misidentification.

Seven people spoke on Malik’s behalf at the 2003 clemency hearing. They described the evidence that was withheld during his trial, the positive impact he’d had on the lives of various friends and family members, and his remarkable record of service within the prison.

Over nearly four decades, Malik has helped establish four different nonprofits to counsel and mentor his fellow prisoners. He also started Washington’s Juvenile Awareness Program, which he describes as “not so much a ‘Scared Straight’ thing, but letting kids know if they didn’t change, there was a bunk waiting for them here at the facility.”

Current King County Prosecutor Dan Satterberg, then chief of staff for his predecessor Norm Maleng, sent a letter to the Board on behalf of several descendants of Malik’s alleged victims. “The fact that Mr. Malik was sentenced to die originally shows the jury found the evidence of his guilt overwhelming and the nature of his crimes outrageous,” wrote Satterberg. “It is not possible or appropriate for this Board to contradict the conclusions of eyewitnesses, the trial court or the jury that heard the evidence.”

When it came time to vote, the board was split 2-2 on whether to recommend or deny clemency. One of those opposed called Malik “somebody who does not conform when he needs to conform,” citing his accumulation of 55 infractions for misbehavior during his 37 years in prison. The offenses included helping another inmate with legal filings, arguing with guards who called him Riggins rather than Malik, and a 1995 incident in which he “called a woman a bitch when she wouldn’t give him a second vegetable patty” for lunch.

The decision, then, rested with the fifth and final board member, who was absent that day. Her decisive vote was never cast. So faced with a deadlocked panel, Governor Locke did what he’d done seven years earlier, again denying Malik’s request for clemency.

On a drizzly gray January afternoon, a crowd of about 35 files into the basement of New Hope Baptist Church, where Dawud Malik’s father once preached. They’re not coming for a sermon. Instead, they listen intently as Felix Luna and Kelly Canary, two Innocence Project attorneys, explain the difficulties Malik will face if he is paroled from prison after 45 years. (Malik’s death sentence was commuted in 1972 when a U.S. Supreme Court ruling resulted in a temporary nationwide moratorium on the death penalty. He was paroled on one murder charge in 1979 and another in 2005, and is now serving consecutive 35-month sentences for the robberies.)

Canary tells Malik’s assembled family and friends about an Innocence Project client named Darryl Hunt, who was freed after 19 years. “He goes to the movie-theater bathroom and can’t figure out how to turn on the sink,” she says. “He stands there until this group of teenagers comes up to him and says ‘Hey, old man, just put your hands under the faucet!’ Can you imagine how humiliating that is?”

The lesson, Canary explains, is that Malik will need the support of his friends and family members when—or rather if—he is released. Malik is scheduled to appear before Washington’s Indeterminate Sentencing Review Board (ISRB) in March, and this time he and his lawyers have a new strategy: They won’t say a word about guilt or innocence.

“It’s not about innocence anymore,” says Luna. “That’s hard, but it’s true. They don’t care. The system has spoken, and they don’t want to admit the system failed him and his family.”

But Malik’s release is hardly a sure thing. Barry Hutton, just a teenager when his father was murdered on his way home from the Lucky Inn, is just one of the family members of Malik’s alleged victims who still oppose his freedom. “They took my dad away from me,” says the 61-year-old Hutton from his home in Edmonds. “And it wasn’t just my family; they wrecked a whole bunch of people’s lives.”

There’s also the ISRB’s track record when it comes to prisoners with commuted death sentences. Of the 14 men on death row with Malik in 1972 when the Supreme Court enacted its moratorium on capital punishment, six have been paroled. All six are white.

Soukup, the prosecutor in 1966, says he stands by the jury’s death sentence, even though he later served as a judge and saw the penalty administered unfairly in cases involving black defendants. “I don’t think [race] played any part in the jury’s decision,” he says. “At that time, anyone that was black who committed a murder was much more subject to the death penalty than a white person would be, but the evidence in this case was really clear . . . I never felt a moment of discomfort about the verdicts in the case.”

ISRB chair Lynne DeLano says it’s unlikely that Malik’s repeated claims of innocence will affect the board’s decision. “I don’t know that I’d find fault with it, but it doesn’t always help either,” she says. “It makes us as people feel better if they’ve accepted responsibility and made an effort to change their behavior and express an appropriate amount of remorse and empathy, but it doesn’t equate to them going out and not re-offending.”

DeLano explains that the more troubling aspect of Malik’s case is the amount of time he has spent away from society. After nearly a half-century behind bars in eight different state correctional facilities, Malik is now the third-longest-serving inmate in Washington. The question, says DeLano, is whether he has become institutionalized: so accustomed to prison life that he can’t function when given the opportunity to exercise free will.

During an interview at Stafford Creek, Malik wears an orange T-shirt beneath a set of overalls that Velcro-close at the chest. He has close-cropped gray hair, a neatly trimmed beard of the same color, and tired brown eyes that make him appear far older than 64.

He is on medication for a variety of ailments, including hypertension and high cholesterol. He was recently hospitalized for a heart condition, and when he was released from the prison infirmary, he got into an argument with a guard over whether he could make copies of his legal filings. The confrontation landed him in “administrative segregation,” the prison’s euphemism for solitary confinement.

Speaking through a glass wall and an intercom that cuts in and out, giving his voice the feel of an old recording, Malik says he believes that if someone had intervened during his youth, he wouldn’t have participated in the brutal robbery of the Hagan family. He had a steady job at the shipyard, he says, but turned to crime because of “greed—stupidity and greed.”

“The ignorance I operated with at that point in time,” he says, shaking his head. “I was watching TV, thinking you could knock someone out and their memory would be gone.”

He goes on to explain that he was often beaten as a child by his strict father, which may have caused him to be violent with the Hagan boy. “There ain’t no excuses and you can’t justify it, but that’s the only connection I can make,” he says. “If God would grant me the privilege [to speak to Hagan], I’d say that I feel God forgave me and I would ask him for forgiveness. And second, I’d ask what could I do for him to bring peace and harmony into his life. Whatever he would ask, I would do that, because I know ‘I’m sorry’ ain’t gonna get it done.”

Malik says he’s a fan of the movie The Shawshank Redemption, and understands that a long-serving inmate’s return to society is often more than they’re able to handle, a sad reality portrayed memorably in the film. But Malik says he’s not the least bit worried. “I don’t think prison walls stop you from being free—they stop you from going where you want to go, but freedom is in here,” he says, putting his index fingers to his temples. “These walls, I’ve not let them hem me in.”

And if the parole board asks him point-blank if he’s guilty, and his freedom depends on him answering yes?

“For the record, I’m not guilty,” he says, after giving the question some thought. Then he offers the kind of answer you might expect from a preacher’s son. “But it’s a mind game. And if it’s a mind game, my release is more important to me. If they want me to play Cain and Abel, then OK, I’ll be Cain. Let me out.”