“In my country, we go to prison first, then we become President.” –Nelson Mandela

I would like to be able to say that I became an anti-apartheid activist in order to overturn an oppressive South African government and to free their revolutionary leader, the great Nelson Mandela. The truth is, I wanted the poster.

From 1982-86, I went to the University of California at Berkeley. The (unofficial) school motto, “Don’t Let School Get in the Way of Your Education,” was the primary reason I chose to attend. (My second reason: “Anywhere but Seattle.”) Walking across campus you’d have a hard time not stumbling into a cause, movement, or student action committee. “Tabling” they called it, and every radical atheist, Bohemian nut-job, animal rights fanatic and, yes, liberal pinko Commie organization in the world had a recruitment table out on Sproul Plaza. I liked chatting up the attractive girls at the Tibetan Meditation booth, buying fresh strawberries from the United Farm Workers, or debating the left-field conspiracy theorists (who, at the time, thought the federal government was eavesdropping on our phone calls! Wackos!) I even attended a Hari Krishna dinner, but was disappointed with the portions, free haircuts, and overall lack of rhythm at the drum circle.

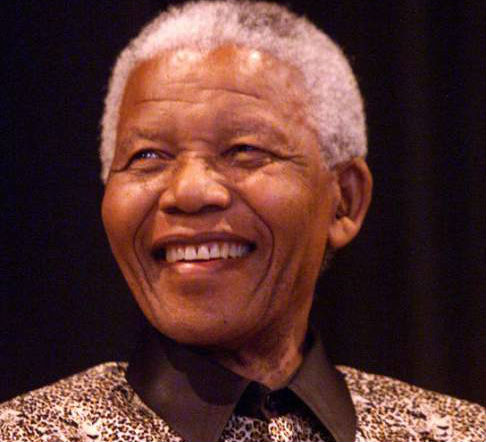

As I mentioned, it wasn’t a cause that drew me into the divestment movement, but a cool poster. In my defense, I was 18 years old – who doesn’t like cool posters at that age? The poster was emblazoned in the rasta colors I was so familiar with from my Bob Marley collection, it used an old-school font (like something from the Woodstock Festival), and featured the face of a man who, now that I gaze more closely, looks a lot like Russell Crowe. A black Rusell Crowe.

I walked up to the table of the UC Divestment Committee and asked one of the nubile attendants who the dude in the poster was (and if I could have one). “That’s Nelson Mandela,” she replied. “ He’s an amazing South African leader who has been in prison for almost 20 years for trying to abolish apartheid.”

I didn’t have the word apartheid in my vocabulary in 1983, and I sure as hell didn’t know where South Africa was (south of Africa, I could have surmised), much less who Nelson Mandela was, or how anything I was doing might have anything to do with … what was that word again? “Apartheid. Racial segregation. Did you know the majority of South Africans are black, and they don’t even get to vote? Not only that, but our tuition dollars are keeping the system in place!”

Indeed, the University of California had over $1.7 billion invested in businesses in South Africa at the time. Though it took me a while, with the help of a brilliant Divestment Coalition leader Nancy Skinner, I began putting the pieces together: tuition dollars, fed into the U.C. System, were then invested in major corporations in South Africa, and those companies actively opposed racial equality, fair pay, or allowing an articulate and brave lawyer named Nelson Mandela to go free. (After college I worked for environmental groups, and always loved to shock consumers by informing them about how their own money was often used against them — such as when Coca Cola fought against recycling bills, Ford and Chevy fought Lemon Laws and the makers of your toilet bowl cleaner fought labeling legislation …with our money!)

While my interest was piqued with a poster, it was ultimately solidified by the power struggle between students and the administration. Finally there was a great example of “the man” getting in the way of something truly important — in this case, freedom for millions of oppressed people living in brutal conditions.

I won’t say my attention never wandered or wavered during my college years. I liked the idea of devoting my time to saving the whales (though my desire to get in between a harpoon and one of our seafaring friends was seriously tempered by sea-sickness), and empowering citizens to take back the democratic process as one of Ralph Nader’s Raiders (who hired me after graduation to work at CalPIRG). But every day I’d walk by Sproul Plaza (re-named Biko Plaza for South African student and writer Stephen Biko, murdered in prison in 1977) and find more and more student protesters holding signs and blocking administration offices and organizing teach-ins about the need to put our money where our mouths are.

I played a minor role in the movement, posting flyers, attending rallies and sit-ins, and staying the hell out of the way of the mace and tear gas which inevitably was to come. (On the morning of April 16, 1985, almost 200 students who had set up camp on Biko Plaza were forced into a big-ass police school bus and detained. I’d like to say I was arrested, but the cops had cleared the place at 6 a.m., long before my conscience was conscious.)

The next day, I was among over 10,000 students who boycotted classes and rallied for divestment on the Berkeley campus. (Skipping class is hardly revolutionary, but I must say it’s uplifting to have your teacher standing next to you at the rally). Once teachers and elected officials joined in solidarity, there was no turning back — the movement had become noticed, national, and had too much momentum to fade away.

The divestment campaign made sense for so many reasons — obviously, apartheid being morally wrong was a no-brainer, but having a proud statesman like Nelson Mandela didn’t hurt. In the midst of the anti-apartheid movement in 1985, after being held for over twenty years in prison, Mandela was finally offered his release by South Africa’s P.W. Botha if he would, “unconditionally denounce violence as a political weapon.” Mandela rejected the offer, saying that only free men could negotiate; he — and his banned organization, the African National Congress — could not and would not enter into contracts.

It took years, but the Divestment Movement was, of course, ultimately successful. (Rather than give students the satisfaction we deserved, the bastard regents at the University of California waited until a week AFTER graduation in June of 1986 to announce their plan to divest their holdings from South Africa). Mr. Mandela was freed (in 1990), deservedly won the Nobel Peace Prize (1993) and became Mr. President (1994), ending racial apartheid in his country once and for all, and becoming the ultimate poster-child for non-grudge holding. (He famously invited one of his jailers to his inauguration.)

Thanks to the Divestment movement, I have carried a different world view about commerce and my part in it. My view, sadly, is often obscured by ignorance and selfishness. I’m happy to boycott Walmart for selling guns, and Paula Dean for being a hater, and Monsanto for being … well, Monsanto. But I have more trouble setting my iPhone aside even though I know it’s been made by a virtual slave teenager at FoxConn in China. Should I divest from technology? Am I willing to look the other way?

Mr. Mandela was released in 1990, but so many are still not free. Hell, we don’t have to go to the Soviet Union or Syria to find injustice; we’ve got prisoners right here at Guantanamo who haven’t been charged with a crime, or been given legal council. I’m not saying they’re innocent — 90-plus percent of ‘em are terrorist-MoFos. But let them lawyer up for godsakes; it’s a fairly basic tenant to our Constitution.

There is much to be done, and it’s often hard to know where to start. Perhaps President Mandela’s lasting legacy will be one of forgiveness. I always thought that if he could forgive his captors after being imprisoned for 27 years, I could at least have a fresh start with my ex-wife.

The notion seems simple enough; acknowledge the other guy’s been a douche-bag — and at times so have you — and for the sake of moving forward and making progress, begin again. But look up “holding a grudge” on Google Images and you get a picture of the current U.S. Congress. And this intractable nonsense doesn’t even make sense. Mr. Boehner did not lock up Nancy Pelosi for 27 years … and she deserves it (for subjecting us to all those horrible red suits!).

Point is, when a visionary leader such as Nelson Mandela passes on, we should at least have the decency to try and absorb a few of his great lessons, and then implement his powerful ideals about equality, education, democracy and forgiveness. We should begin to use Mr. Mandela’s incredible story to begin building one of our own.

I wish there was a poster for that.