Growing up, Emily’s mom drifted in and out of her life. Disappearing when she was using, home when she wasn’t. When she was gone, Emily and her younger brother stayed at a neighbor’s house, or sometimes an aunt’s, until their mom showed up again. Other times, Child Protective Services would intervene, plucking them out of their childhood home. But CPS always seemed to come at the wrong times– taking them away during one of their mom’s sober periods, bringing them back when she was using again.

Emily (whose name we’ve changed at her request) ran away for the first time at 12 years old.

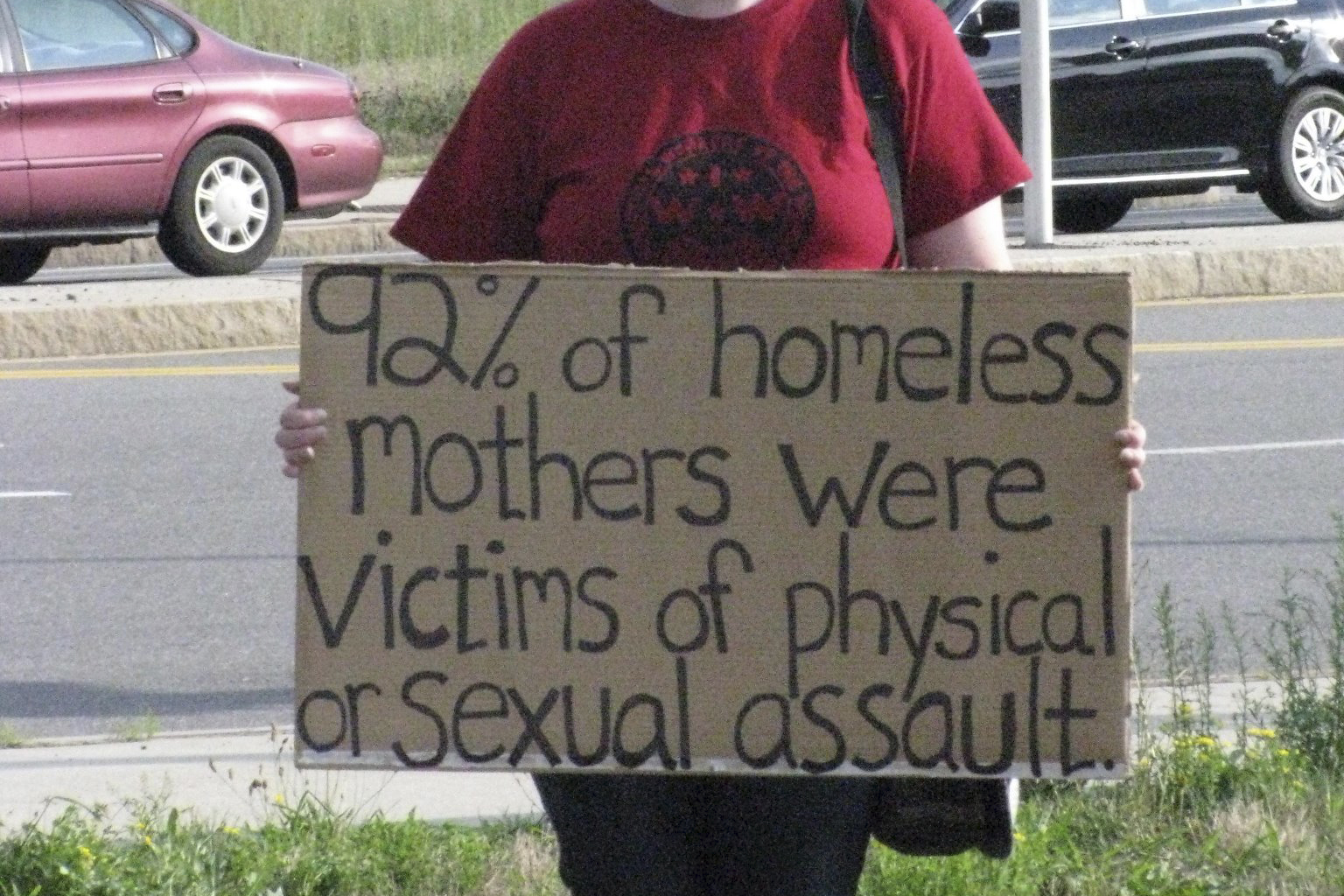

At 13, she got caught up in a gang and hooked on methamphetamine. When her mom shipped her off to her grandparents’ in Montana with the hopes of getting her away from gang life, her addiction grew worse. So she came back home, only to be regularly raped by her mom’s new boyfriend.

Emily took to the streets again at 14, figuring she’d be safer there than at home. When she turned up at a shelter with extensive injuries, the shelter went to court to finally take her from her mother permanently. On paper, that’s when things should have started getting better for Emily. She was out of an abusive home and on her way into the care of the state’s child-welfare system.

Yet in reality, little changed in her life. In the aftermath of her court case, the shelter, CPS and her Guardian ad Litem—a volunteer who is assigned to help children navigate the court system—all assumed one of the agencies would take charge of Emily, when in fact, none of them did. Instead, she was put into a group home where she was allowed a three month stay before facing the decision of returning to a physically and sexually abusive home or ending up back on the streets.

Emily, who today works in Seattle at a youth shelter, is still sifting through the muddled details of why she fell through the cracks of the foster care system, but it’s apparent she is not alone in this situation. According to a recent federal study by the Administration for Children and Families, 50.6 percent of Seattle’s homeless youth have stayed in a foster home or group home. According to the local homeless youth service Teen Feed, “It is estimated that over 1,000 youth and young adults are homeless on any given night in King County.” Other studies suggest that those teens will continue to struggle with homelessness in their adult lives. Taken together, the research suggests that part of Seattle’s current homelessness epidemic stems back to the way we handle kids from broken homes and desperate situations.

“When [the state] really needed to intervene … they didn’t intervene,” said Emily. “They just labeled us CPS case and ran us through this pattern of open, close, open, close.” When the state finally did take charge, they failed to provide any sort of long-term support.

Seattle foster care advocates uninvolved in the federal study say its findings match what they see in the field, and say the numbers speak to a child welfare system that is geared toward younger clients.

“The foster care system has not made adolescents its highest priority,” said Fred Kingston, director of Youth Programs at The Mockingbird Society, a youth advocacy organization in Seattle. “My opinion is that the children’s administration in our state has abdicated its responsibility to older youth in the foster care system and has concentrated on meeting the needs of infants and young children.”

Both social services and parents looking to adopt tend to prioritize younger children, says Kingston. They’re more vulnerable, whereas adolescents can at least partially take care of themselves. Plus, adoptive parents usually want cute babies instead of angsty teens, he says. “So adolescents are stigmatized, traumatized and their needs are largely ignored.”

When kids enter the foster care system, they’re checked off as “taken care of,” said Annie Blackledge, executive director of The Mockingbird Society. This leads to scenarios like Emily’s– where the state takes charge of a teen then wipes their hands clean without placing them in any sort of stable environment.

“If you ask the child welfare system how many youth in the system are homeless, they will say none,” adds Kingston. “Because if you are in foster care [or a group home], there’s this point of view that you have access to housing by virtue of being in the system. Whether or not you’re on the run from care, living on the streets, stuff like that.”

In fact, the foster care system doesn’t even collect data on kids who become homeless in the system; only by interviewing teens who are living on the streets and in shelters did the Children and Families Administration arrive at its figures of homeless teens with a history in foster care.

In essence, homeless youth in the child welfare system don’t exist on paper.

Youth advocates emphasize that youth homelessness is not purely a result of state agencies. Outside of the foster care system, kids leave home for a fairly consistent set of reasons, said Kingston: home isn’t safe, home isn’t supportive or home doesn’t exist.

“Many teens are driven to the streets due to the level of uncertainty,” said Megan Gibbard, exectuive director of a new national youth advocacy organization called A Way Home America. “They think they might be able to do better on their own.”

A number of efforts are underway to address the problem.

For the holes in child welfare data, the Research, Data, and Analysis (RDA) division of state Department of Social and Health Services recently began using integrated data analysis to get a more holistic view of youth in the foster care system. This approach cross-references data across multiple programs in order to, for example, find names that appear both in the foster care system and a Housing for Homeless Youth program, effectively pinpointing homeless youth in the foster care system.

Washington has also established the Office of Homeless Youth Prevention and Protection Programs, which is responsible for drafting a statewide action plan aimed at reducing youth homelessness. Chair of the advisory committee Casey Trupin said the plan, due on December 1st, will address the intersection of foster care and youth homelessness.

Federally, Gibbard says the up-and-coming program A Way Home America will also focus on homelessness in the foster care system. Part of this work will be an ask of Congress to create better care for adolescents in the foster system. Gibbard said she suspects there will be requests for an alternative system, one tailored for adolescents specifically.

The solution, Gibbard says, lies in “the recognition that youth homelessness is unique, both in its causes and in the strategies and solutions to address it.

When the foster care system failed her, Emily had to work her own way out of things. At 16, she took multiple jobs and sold drugs to get off the streets in time to give birth to her daughter.

“My family legacy is that everyone is in gangs doing illegal activity, selling drugs, stuff like that,” said Emily. “I decided, ‘I don’t want that for my child.’”

So she stopped using, started going to school, and got the job at a youth shelter. Five years later, she has a degree in Social and Human services with a focus on policy and social justice and has a job managing a Seattle youth shelter.

Looking back, Emily said she can see the flaws in the system.

“The problem is that the system is set up with very black and white solutions,” said Emily. “But you need multiple solutions across the board for different types of youth.”

Corrections: Due to an editing error, the organization Teen Feed was misidentified in an earlier version of this story. The story also misidentified the new national youth homelessness organization A Way Home America. The story has been updated to correct these errors.