About four years ago, staffers at the Catholic Seamen’s Club of Seattle began to hear troubling things about a ship in port. Rumor had it that the ship’s Japanese captain had shoved one elderly crew member and smashed his hard hat over the head of another man, who left for shore the next day and never came back.

A union inspector who went aboard to check on things found the captain “in the hold, practicing his karate,” says Seamen’s Club director Tony Haycock.

When Haycock boarded the ship, crew members ushered him into a room and locked the door. Haycock recalls one of the men telling him, “If he forces us to go with him again to sea, the young guys are . . . going to get him and throw him overboard.” Though the Bible often favors such popular uprisings, Haycock, a Catholic priest, decided to take the pacifist route. He went to the captain’s office, confronted him with the allegations, and suggested he leave the ship.

To Haycock’s surprise, he did. “The captain said, ‘I’ve shamed my race and shamed my profession, and I will never go to sea again,'” Haycock says, with some satisfaction.

For over six decades, the volunteers at the Catholic Seamen’s Club of Seattle have tried to assist sailors in such times of need. Their support has included gift bags and shipboard Masses—including services in the wake of Coast Guard safety drill catastrophes. Just this March, a Chinese longshoreman drowned during such a drill after his lifeboat capsized. And before that, another sailor died when his lifeboat plummeted into the water and left him dangling above it from a rope. “He got tired,” says Haycock, “and he dropped and went into the boat headfirst.”

The Seamen’s Club, located on the top floor of a two-story Belltown building, features a remembrance wall dedicated to such naval tragedies. Newspaper articles pasted to it include a variety of grim headlines: “Body of fisherman, 51, pulled from Hood Canal,” “Search suspended for vessel and crew,” “Coast Guard divers’ deaths explained.” The fatality on the lips of club staffers, however, is the potential demise of the club itself.

The club has the misfortune of being situated atop the Battery Street Tunnel, which will have to be altered if the Alaskan Way Viaduct is replaced by a tunnel. Last week, Gov. Christine Gregoire announced that the question of how to replace the decrepit elevated roadway should be put to Seattle voters this spring. Obliterating the Seamen’s Club, then, is “almost a sure thing under the tunnel scenario,” says Ron Paananen, project director for the Alaskan Way Viaduct and Seawall Replacement Project.

In a way, though, a spectacular takedown at the hands of a wrecking ball is preferable to the slow death the building is now experiencing. Typically, only a handful of visitors chat at the club’s snack bar or sit near the windows, contemplating the horizon. Excitement this past week came in the form of a kitchen-ceiling leak: Men gathered to catch the drips with trays and discuss plumbing. But then, when the leak petered out, it was back to quiet.

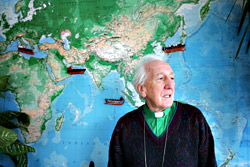

“In the past, there used to be loads of guys coming in here from the ships. We picked ’em up, or they came in taxis,” says Haycock, a spry 70-year-old whose blown-back hair and squinted eyes suggest he’s constantly facing some staggering gale. “Now we don’t have a great lot of people. We have to go out to the ships.”

Operated by the Catholic Archdiocese of Seattle, the ecumenical Seamen’s Club is one of many similar enterprises that serve the world’s ports. The first “clubs” were simply groups of well-wishing parishioners who would rush to the port whenever ships arrived. Then, buildings were erected to provide sailors with a safe place for fellowship. In areas with many small ports, such as New England, the seamen’s clubs recently have become mobile: Workers ride around in RVs outfitted with libraries, meditation rooms, and little chapels. “That’s the future, I think,” says Haycock.

The Seattle club gives sailors mailboxes; lockers for their fishing boots, coats, and knives; phones; Internet access; and a foosball table. A commissary sells shaving cream, bubble bath, and copies of Haycock’s own folk-music CD, Home From the Sea. The bar provides burgers, bowls of oatmeal, and $2 beers—a nice price that used to be nicer, before the club jacked it up to ward off landlocked barflies.

“This is almost like a sanctuary for merchant seamen and fishermen,” says 54-year-old Randy Yelverton, drinking coffee at the bar. Yelverton sometimes goes up to Alaska on boats to size and sort cod, pollack, and the much-desired “idiot fish” (“They’re red, and they’re very expensive,” he says), but is currently between jobs and living in transitional housing. He fills his time by hanging at the club, where he receives job references from Haycock and is able to bum rides to ships from volunteers. “Around town,” he says, “I can tell you that I know more [fishermen who] are doing what I’m doing than having their own places.”

Besides providing a warm space for the temporarily homeless, the club can list on its sheet of neighborhood improvements the support of a fine-dining establishment. The club’s first floor is rented to Del Rey, a swank joint featuring grilled asparagus with Parmesan oil and black truffle macaroni and cheese. Before Del Rey, the space belonged to a seamstress who specialized in leather goods.

“About 15 years ago, it was dangerous to be in Belltown [at night],” says Haycock. “It’s ‘Gentrifiedtown’ now. . . . In the last five years, we’ve had condos going up all around us, which has helped us in a way, because our tenants pay more rent.”

That rent in turn goes toward things like the maintenance of the club’s two minivans and its Stranded Seafarers’ Fund, which is earmarked for the repatriation requests that roll in each year. About 10 years ago, for instance, a group of Bulgarian fishermen flew into Seattle for jobs they soon found out didn’t exist. “It was just a pure scam,” says Everett Savage, a Lutheran pastor who works at the club. “They were bewildered.” Staffers let the men sleep on the floor for two weeks until they could collect enough donated cash to fly them home.

The club’s outreach efforts have become more common in recent years. Part of that’s due to technology: Since containerization began around 25 years ago, says Haycock, ship companies try to load up and depart almost overnight, leaving sailors with no time for shore leave. Another reason Haycock and his followers trek to a couple dozen ships a week is because foreign sailors without U.S. visas are barred from coming ashore, thanks to post-9/11 regulations.

On a recent Thursday afternoon, Haycock drives to Terminal 86 in one of the club’s vans, which transports sailors to Costco to buy food, Target for jeans, Kmart for electronics, and Victoria’s Secret for spousal gifts. Passing a guard booth as well as two barbed-wire fences, Haycock arrives at the dock to find the Bruno Salamon, a massive grain ship that’s topping off its holds with soybeans.

Haycock tramps over the dock carrying a garbage bag full of “ditty bags”—Seamen’s parlance for Christmas packages of soap, socks, and woolen caps. With the sour smell of fermented grain in the air, Haycock climbs a staircase to the ship’s deck and is escorted by its Chinese crew into a little room, where the captain, 36-year-old Wang, gives him a cup of green tea. While Haycock sells phone cards to sailors who can’t go ashore to call home, Wang offers his thoughts on the United States’ unique maritime policy.

“[Crew members] feel unhappy, like it’s unfair,” he says. Wang, with his visa, is able to visit the aquarium and the Space Needle, while half of his crew must stay aboard. “Some watch TV, and some play table tennis,” he says, while others just have to watch the city and whatever entertainment the marine life provides.

“Some call it an iron prison,” says Haycock, departing the Bruno Salamon. “It’s all iron, and you can’t go ashore.” Except for one difference, he says: “You might drown.”

Haycock and his crew talk a lot about the “plight of the seafarer.” Back at the club, cook Bob Barrett, 79, takes a break to summarize what he thinks the average Seattleite’s view of the shipping industry might be. “During World War II, you had the Liberty ships, and maritime service was more recognized—mainly because they were being torpedoed by the Germans and sinking. There was kind of a heroism role,” he says. “[But now,] people don’t realize they’re still moving goods and services around the globe.”

Haycock is blunter about it: “The ships are sort of big objects, and they don’t believe there’s anybody on them.”

On rare occasion, a nonseafaring Belltown resident will enter the club on a curiosity mission. “They want to know what it’s all about,” says Barrett. He tries to fill them in. With the possible teardown of the club, however, Barrett and the others will have to find a new home to engage in such education attempts. One idea is to combine the club with an Episcopalian center near Terminal 5 in West Seattle. But there’s still “a big question mark about the future,” says Haycock.

That means longtime club tenants might have to find a new place to linger. One of these regulars, a retired Ethiopian ship engineer who calls himself Taffé, sits in a back room alone, in the dark, in front of a big-screen television. He comes to this spot to watch the TV, which he says is “like theater.”

“I started [sailing] when I was a kid, to see the world. I’m fed up with it. Wherever you go is the same,” says Taffé, who’s 60 and sleeps at a shelter. “I don’t have friends. . . . I want to sit and be left alone, that’s all.”