THE SEATTLE PIGS, at long last, are no longer on parade. The fiberglass swine, installed all over downtown last May for the entertainment of summer tourists, have been cleared from the streets and will be auctioned off this weekend to raise funds for the Pike Place Market Foundation.

For Northwesterners in the know, however, a far more enticing—and far less cute—passel of hogs remains at large. Wild pigs are afoot in parts of the Olympic Peninsula. And hunters have been swarming into the region to take a shot at them.

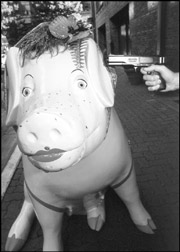

The pigs, heretofore unknown in our area, first started showing up this past spring, when people living in and around the town of Montesano suddenly came upon the dark, snorting creatures in their front yards. Thirteen-year-old Zach Fry had to blow away a pig in the family garden on Mother’s Day when the 70-pound porker came chasing after his little brother, Curtis. The boys’ father, Don Fry, says his family didn’t bother eating the animal: “It was so ugly, we didn’t know if it would be good or not.” (He’s since heard that they make fine eating, however, and says he won’t make that mistake again.)

Faced with reports of pig sightings, and concerned about the animals’ environmental impact, the state Department of Fish and Wildlife this summer called on hunters to go after them, setting off a swine-seeking frenzy. “There is significant pent-up demand” for this kind of thing, observes Jack Smith, a regional wildlife manager for the state.

At Montesano’s main hunting-supply store, Western Sports Unlimited, proprietors Dick and Rogene Gates have been fielding hundreds of phone inquiries about the pigs each week, as well as dozens of visitors each morning. “It’s something new to everybody,” says Dick Gates. “I can’t believe the interest in it.”

Most of the time, the government rigidly controls the hunting of game animals—more so than perhaps any other form of recreation. Everything from the kind and size of critter you can take, where you can take it from, during what months, and with what weapon, are all prescribed in detail by the state. Each kill carries a fee and you are required to report your activity, even if you come away from the season empty-handed.

But when it comes to pigs, there are no rules and no limits. They’re not native creatures, so the state does not consider them wildlife. “There’s no tag, no license. You can hunt with a stick if you want,” says Delbert Vance, who works behind the counter at Western Sports. In states with active recreational pig hunting, such as Texas, California, and Florida, private landowners generally charge hundreds of dollars a head for the privilege of shooting pigs on their property. But you can come and git all the bacon you can eat in southwest Washington for free. For hunters, it’s like being a pig in you-know-what.

THESE AREN’T YOUR pink and hairless barnyard pigs from an E.B. White story. They have shaggy dark hair, sharp tusks, a long snout, broad head, humpback, and 42 teeth. On the counter at the Montesano gun shop, a 1968 edition of the Sportsman’s Guide to Game Animals is propped open to the chapter on wild pigs. It describes the creature as “agile, strong and vicious.” The pig is “quick to anger . . . [and] slashes with its tusks at the slightest provocation.” It can “disembowel a dog or tear open [a person] with only a few slashing cuts.” In Europe, the book says, boar hunting “was considered a sport for only the bravest men.”

The pigs’ menacing grunt “makes your hair stand on end,” says Larry Willard, 45, who went out for a pig hunt in July. Willard, assistant manager at an automotive shop near Montesano, drove to the edge of a clear-cut north of town, then hiked in a few hundred yards down a logging road and out onto a gravel path. All of a sudden, he heard “a loud grunt, like a bark,” a few feet away from him in the tall grass. Then a pig ran out and into a clearing, where Willard shot it with his rifle.

He was shocked when he saw the animal up close. “I was expecting like a white- and brown-spotted domestic-style hog,” he says. “This had a hump behind the shoulders and long hair. It’s a wild, wild pig.” Willard got the carcass back to his house immediately, skinned it, and hung it in quarters in a spare refrigerator. “I ate the backstrap and the ribs off of it,” he says. “I barbecued it, and it got real dry. It doesn’t have much fat.”

Technically, the state considers these pigs to be feral—i.e., formerly domestic—but there’s no telling when they might have last seen a sty. Professor Bruce Coblentz, a wildlife ecologist at Oregon State University, says that pigs “revert pretty quickly back to wild type” once they’ve escaped from the cozy confines of the barnyard; the impractical domestic genes get selected out fast. “In a few generations, you start getting pigs that are shorter, thinner, with bigger heads and smaller hind legs.” Genetically speaking, these feral pigs are “somewhere in be-tween a pure-blood Russian boar and your modern pig,” he says.

No one knows where the peninsula pigs came from. But rumors and conspiracy theories have become as much a Montesano industry as timber. Most residents are convinced that these pigs could not possibly have appeared in such numbers through any kind of natural mechanism. “My uncle was logging in these woods since the ’30s, and I never heard of a pig,” says one Montesano local, hanging out at the gun shop. “I’ve never seen a pig, and I’ve been hunting around here since I was 14,” says gun shop owner Gates. They and others suggest someone must have deliberately trucked the pigs into the woods, perhaps from California, and set them loose.

“These things don’t just pop up like mushrooms,” observes Professor Coblentz. “Someone has to bring them in and release them. You never know the origin, unless you can catch someone in the act.”

But Jack Smith of the Fish and Wildlife field office in Montesano believes that purely natural pig processes could be at work. Feral pigs are believed to have been present for years on the Quinault Indian Reservation along the coast, and a few may have scattered outside it. Smith notes that pigs have litters twice a year and reach sexual maturity in only six months. With some good reproductive success, seven or eight pigs “could be multiplied by 10” in no time. “We had a pretty darn mild winter,” he says. “Maybe they just had a good year.”

MONTESANO IS a tidy, storybook town in southwest Washington, best known as the place where Kurt Cobain spent much of his miserable youth. The first stop for would-be pig hunters is usually Gates’ gun shop on Main Street, where, several times a day, Dick Gates pulls out his maps and instructs his visitors as to roughly where the pigs have been spotted: in the woods between the Wynoochee and Middle Satsop river drainages and out by the Deckerville Swamp.

From behind the counter, Gates looks out on the pig hunt with a mixture of amusement and opportunism, cheerfully fanning the excitement even as he laughs about it with his regulars. Most of the pig hunters these days are out-of-towners, and many, says Gates, are inexperienced—you can tell from the fact that they ask him where the pigs can be found. “I’d never ask someone where he got his elk ’cause I don’t want him to lie to me,” says Gates.

Gates says he has confirmed reports of nearly 60 pig kills since last spring, though if all the rumors and boasts were to be believed, there’d be several hundred. Recently, the success rate seems to have fallen off. Over the last several weeks, Gates has heard of only one successful pig kill—and that was by a woman who totaled her car hitting one on a county road. “The media’s made it out like you just show up and shoot a pig,” says Gates, referring to some TV news reports that aired in August. “People aren’t familiar with our terrain. You’re hunting something knee-high in waist-high brush. It’s almost a jungle in some places. That’s why pigs love it.”

Larry Willard, who has followed up his early success with several fruitless pig outings, figures that with all the hunting pressure, “they’ve been scattered real bad. They’re hiding out, a lot more gun-shy.”

“They’re difficult to hunt because they’re built low to the ground and they tend to stay in heavy cover,” says Jack Smith of Fish and Wildlife. “You could be in the newest clear-cut and there’s enough vegetation that you could walk right by ’em and never see them.” They also travel in a gang, like elk. “You can spend entire weeks and never find an elk because they’re in groups,” says Smith. “Pigs are kind of the same. A group of animals is harder to get close to. There’s more eyes, ears, and noses.” He hazards that 90 percent of pig hunters will never encounter their prey.

“They can learn to avoid things pretty quickly,” says Professor Coblentz. He describes wild pigs as “wary as a deer, with a little of the sneaky cunning of a coyote.”

The area where the pigs are supposedly residing is a vast, scrappy, unbeautiful landscape of clear-cuts and former clear-cuts, most of it part of a half-million-acre tree farm belonging to Weyerhaeuser that stretches out north from Montesano. By long- standing custom, timber companies have generally allowed public access to their giant tracts of timber, in part because it would be impossible to fully prevent people from entering, in part to maintain good relations with surrounding communities, and in part because hunters help keep the wildlife in check.

Circling the area in his truck one afternoon, Jack Smith pulls up to the empty house of the Compton family. The Comptons reported hearing grunting and rustling sounds at night a few weeks ago, and a strip of land in front of their home was tromped on and full of holes. Fish and Wildlife officials came out and spread flour to capture tracks and found the deerlike look of pig feet. Now Smith can see what looks like fresh pig signs in the heavily trampled and gouged-out yard.

State officials are concerned about the environmental damage that pigs can cause. “People say, ‘Well, it’s just a pig.’ But every place they are, they’re a major problem,” Smith says. Pigs root around and dig up bushes and destroy riparian areas, sending silt into fish-bearing streams. They eat berries and other food that might otherwise go to support native wildlife like bears and elk.

“They can be tremendously destructive to a natural system,” says Professor Coblentz. “It’s sort of like having a rototiller running around in your forest.”

So, on its Web site, in press releases, and in person, Fish and Wildlife staff plainly encourage people to blow the critters away. “We want them all dead,” says Smith.

The pigs have their defenders. Wayne Johnson of the Northwest Animal Rights Network recently contacted Smith to register his disapproval of Fish and Wildlife’s approach. “We think it’s outrageous that the department of wildlife has invited people in to kill these pigs,” says Johnson. “There’s no reason for that. At the very least [the department] could have remained neutral. These pigs aren’t doing anything wrong. They are only a potential danger maybe to some plants. And so we’ve got another [instance] of human beings intervening where we have no reason to intervene, and animals suffering as a result.”

The alarm over pigs is even greater inside Olympic National Park, about 100 miles north of Montesano, where there have been several oinky encounters and no hunting is allowed. “If this population takes off, it is a very big deal. It’s about the worst thing going right now” in terms of alien species, says wildlife biologist Patti Happe of the National Park Service. Pigs “are hard to eliminate,” she says. “They hang out in the woods; they’re not real vulnerable. Elk have one [offspring] a year. Not these guys; they have litters. They cause incredible amounts of damage. It’s a bad deal all the way around.”

“The thing about pigs,” says wildlife biologist Coblentz, “is they’re so generalist”—i.e., such pigs. “They can survive on so many different things, from bulbs to worms to every little vertebrate or invertebrate that they root up in the soil. As long as conditions are favorable, they will spread their range and increase in number.”