Just nine months after he defeated the incumbent mayor as a little-known write-in candidate, crusty Korean War veteran Cy Sun stands at the pinnacle of another stunning accomplishment: The 82-year-old and his 103-year-old town of Pacific could both go down the tubes.

Elected on a promise to clean up corruption in the bedroom community of 6,800, Sun is now accused in a recall effort of breaking the law and stubbornly mismanaging Pacific to the brink of collapse. The mayor calls such charges the ravings of opponents who have falsely accused him of lying about his war medals and cheered as he was arrested by his own police force for trying to enter a city office.

Sun insists his small town can be saved, and even councilmember John Jones, who ran against Sun for mayor last year, doubts rumors of the municipality’s imminent demise. Then again, Jones says, “Anything’s possible when you have a mayor who enjoys being disliked.”

When he’s able to hear such dislike, that is. The elderly mayor’s hearing is so bad—a constant ringing from a grenade explosion more than 60 years ago—that he’s unable to preside over city council meetings. At one recent session, when he announced he was turning over the gavel to a councilmember because he couldn’t pick up the discussion, some audience members laughed at his predicament. “Why is he even here?” asked one woman.

“I’m sorry I have this physical defect,” said the mayor, born in Makawao, Hawaii, to a part-Hawaiian mother and a Korean father he never knew, and who speaks in soft, measured declarations. “I’m not afraid to hear your comments. I know all of you have a lot of comments. I received the documents for recall today. I favor the recall. I want the recall. I want the voters to decide. Now you think about it. I served my country. This is why I’m here.”

Sun—sinewy, balding, and attired as usual in jeans, running shoes, and a ball cap—then walked slowly out of the council chamber with a steely gaze at the crowd, peering over the top of his bifocals. He moved with some pain, bearing the chronic aches of the grenade shrapnel he carries around. A machine-gun slug tore out one of his kidneys, and a North Korean bullet is lodged near his spine.

Bent by age, he palpably bears the weight of his past and current wounds. His Capra-esque start as mayor has taken a Wes Craven turn—the write-in dreamer who could end up written off as the town nightmare. Some who mock him have provoked both tears and anger; after departing that recent council meeting, Sun’s eyes watered as he referred to the audience as “savages.” But he insists he enjoys a good fight, even if he seems to continually pick the wrong ones.

Since his election as leader of the sleepy town straddling the King/Pierce county line near Auburn (Sun got 464 write-in votes to beat incumbent Rich Hildreth, whose 401 votes included 16 from the Pierce side of Pacific), the new mayor has fired or forced out all his department heads, including three police chiefs. Pacific’s insurance carrier, worried about rising liability due to the management vacancies, announced it would drop coverage at the end of the year, putting the town’s future in doubt.

At the same time, Sun was feuding with the city clerk, locking her out of her office. Sun was then locked out of the same office by the city attorney, who worried the mayor would tamper with documents. When Sun tried to physically force his way in, he was arrested by Pacific police officers, whom he tried to fire while they were cuffing him. The city council and police both issued votes of no confidence against him, with the cops asserting he’d improperly ordered them to investigate a political opponent who’d falsely claimed that Sun once bragged he had been Henry Kissinger’s personal physician and a stand-in for Hawaiian nightclub star Don Ho.

Subsequently, one councilmember, ex-Marine Gary Hulsey, publicly challenged Sun to prove he’d earned his war medals. When the mayor did so at an emotional public ceremony where he presented medal citations, the councilman privately apologized. Hulsey was then himself outed when news spread that the councilman had never informed voters he was a convicted murderer.

Sun was also suddenly being pursued in civil court by a woman who accused him of molesting her more than four decades ago when she was a teenager, even though her family had previously sued him and lost. The Aug. 1 lawsuit made a splash on TV and in the papers, and rocked Sun on his heels. (What has made hardly a ripple in the news cycle, however, is the fact that the woman has now quietly dropped the suit.)

His detractors call him America’s most cantankerous small-town mayor, a time bomb in the town a California real-estate huckster founded a century ago, naming it Pacific because it appeared so peaceful. “Cy has turned everything around for the worst,” claims ex-mayor Hildreth, who feels the balanced budget and rainy-day reserve he left behind is now in a precipitous dive under the new mayor. “Personally, I think it’s just stubbornness, not any kind of rational strategy” that drives Sun, Hildreth adds. “People who have a tendency to distrust government are going to fall for his claims of corruption. None of the stuff he claimed holds water.”

Hildreth feels his mayoral career was torpedoed in part by opponents who launched a campaign website called anybodybutrich.com, which is still in existence. The site didn’t endorse Sun, but echoed his complaints, citing instances of “the apparent unchecked petty corruption of Mayor Hildreth,” including his alleged misuse of a city credit card—charges of which Hildreth was cleared.

Sun has his dogged admirers, though they may be dwindling. Kevin Cline, for one, thinks Sun is just the disinfectant Pacific needed. “He is brutally honest and doesn’t try and sell a load of crap as a brick of gold,” says Cline, 30, a single father who runs a temporary labor business and lost his bid for a city council seat last year. “He raised no money and made his own signs. His strategy consisted of knocking on every door and handing out a poorly written but heartfelt plea to support him as a write-in. The rules say he shouldn’t have won.”

Just wait, Cline adds: “History will vindicate this man just as it has others who, like Cy, were willing to stand alone for what was true, right, and just.”

Jeanne Fancher, who covers city hall for her local blog, Pacific City Signal (pacificcitysignal.tumblr.com), says she was willing to wait and see how Sun performed in office. Today she’s seen enough. Sun—a former Boeing engineer and Oregon farmer with no political experience—was an unqualified candidate whom voters winked at, she feels.

“I think if the media had done its job prior to the election, finding out who the real Cy Sun was,” says Fancher, “we wouldn’t be here now.” The candidate issued misleading campaign material, getting names and details wrong in his claims of local corruption, she claims. His low-key doorbelling and write-in campaign is “a study on how a small town without its own news system can be bamboozled by someone who believes everything he thinks,” she says.

Don Thomson, the 66-year-old chair of the Committee to Recall Cy Sun, says his mission “is to remove Cy Sun before he destroys the city”—once farmland, now a residential suburb whose main intersection, Third and Milwaukee, consists of the city hall, a small grocery, and a church. “If we don’t get him out of here by December, we won’t be a city,” adds Thomson, a retired military veteran who, with his wife Shirley, volunteers to deliver meals to local seniors. He’s usually good-humored, but Sun’s antics have gotten his dander up, he says. He took to attending council meetings, where he regularly stands up and asks the mayor to do the right thing and resign—or sometimes just tells him “You’re fired!”

Thomson thinks Sun invited the misery he endures. “The biggest enemy he has is himself,” says Thomson, citing the mayor’s tendency to slash projects and city staff without understanding the consequences. Adding up the cost of legal claims (already more than $2 million), project overruns, grant penalties, and city-hall understaffing, Thomson calculates, “It’s estimated that for every 25 cents the mayor claims to save, it’s going to cost us $3.”

Robert Smith, former Pacific councilmember, news reporter for the old Auburn-Globe News, and a next-door neighbor of Sun’s, says voters weren’t fickle in voting for an unknown to lead them, “they were outraged” over years of municipal ineptness. “But Cy blew it,” Smith says. “He turned out to be another symptom of the disease of Pacific. It’s inbred here. The only solution now is you let the town go out of business, unincorporate, and let someone come in who is not tainted.”

Removing Sun won’t solve all the problems, Smith adds. After he read that some recallers were vowing to “take back Pacific,” he went straight to his blog, speedtrapcity.blogspot.com, and responded. Restoring the halcyon days of life in a small town was commendable, he thought. But surely no one wants to take back “a government that racially profiled; used motor-vehicle ticketing as a revenue tool . . . [and] conducted a police raid on a local church in pursuit of a youth who was skateboarding in the city park,” he wrote.

He cited one past public official who was stopped for DUI, failed a polygraph examination on whether he’d threatened his wife’s ex-husband with a handgun, threw tantrums at city-council meetings, and told probationary city employees to view porn with him on city time. “You can’t possibly want back a city that tried to suppress a civil-rights march protesting police misconduct,” he said. “You folks can’t possibly want that restored.”

Smith and others agree that Sun took wise political advantage of a timely distrust of city hall and higher taxes with his mostly unproven claims of corruption, as laid out in flyers he distributed. His only real campaign appearances were made door-to-door as a kindly old man vowing to clean up Dodge. No one seemed to know what specifically he had in mind—Sun included. The mayor admits that voters likely didn’t know whom they were electing, and his action plan basically consisted of just throwing the rascals out once he identified them, he says. “I’m not a politician. If I say I’m going to do something, I’m going to do it.”

As things turned out, “it” was a plan to paper Pacific with pink slips. As a political neophyte, Sun skipped the typical new-mayor honeymoon period of learning the ropes and tinkering with change. Instead, he charged into city hall much as he’d gone at the enemy on Heartbreak Ridge: firing away, sending three top managers packing in the first month. He makes clear that his mayoral strategy is influenced by his compelling experience as a grunt with the Army’s 23rd Infantry Regiment, including the 1951 battle of Hill 851 on Heartbreak Ridge in Korea, a war in which Sun quickly rose to master sergeant and won the Silver Star and the French Croix de Guerre.

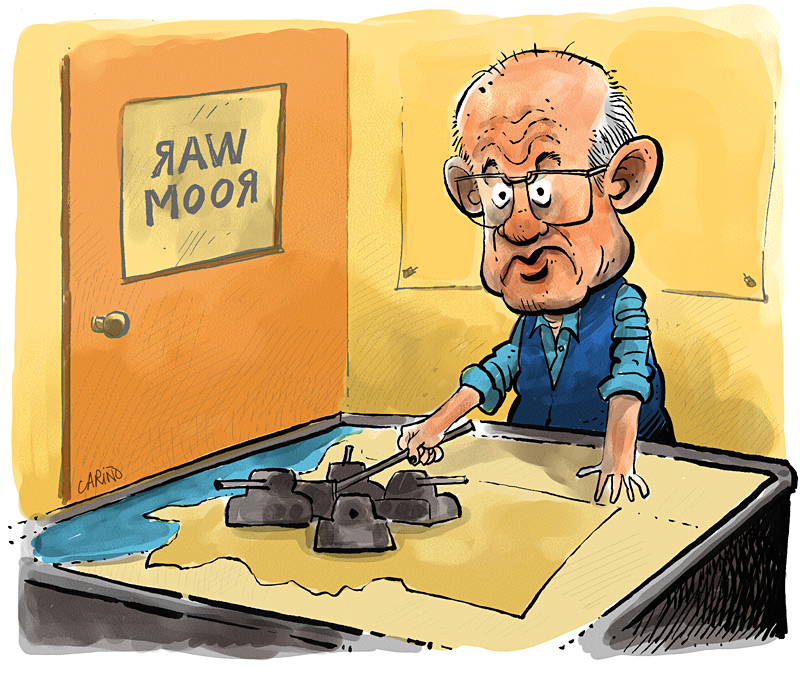

“I went through hell and back,” he says in a chat in his newly launched “Control Room,” a converted conference space where Sun writes his thoughts on a whiteboard. He rises several times and maps out how he came from a rear position for several attacks, in one of them cradling a machine gun in his arms with the cartridge belt draped over his shoulder, mowing down a field of enemy soldiers. “I did that and I’m going to sit around and watch this corruption go on? Now you tell me that I’m gonna let it go on after I went through that. And I’m going to live in the same kind of mess—dirt and filth? Hey, wake up. I’m not gonna do that. As long as I’m breathing the air, I’m not going to be a hypocrite.”

He volunteered for the Army at age 17 in Hawaii, just as he volunteered for duty at age 81 in Pacific. He wanted to be a leader, he says. As mayor he’s paid $750 a month, a salary he returns to the city because it needs the money more than he, Sun says. Yet why endure this war—much of it self-made—for nothing?

“It’s hard for me to understand myself,” the mayor says, doffing his ball cap and rubbing his bald spot as he pauses to think. “Mainly it’s because there’s corruption, the same if there were an enemy outfit in there. I want to attack it.”

Sun’s Pacific blitzkrieg has been memorable hand-to-hand combat, with such caught-on-tape action sequences as his fighting his way through a web of police tape to get into a city office. If his eight-month saga were a war movie with a message, it would star Slim Pickens as the wa-hooing mayor, seemingly riding his own Dr. Strangelove bomb to oblivion.

Flush with a 63-vote victory he considered a mandate (though, due to low turnout, he was elected by just 18 percent of the town’s registered voters), Sun in January canceled a contract to purchase five new police cars, opting instead for four. City Clerk Jane Montgomery says in a sworn statement that she and city Finance Director Maria Pierce were told by Sun not to tell the police chief. When Chief John Calkins heard the news at a council meeting, he blew up, shouting at Pierce. (Fancher reported in the Signal that “they were practically nose-to-nose. Ms. Montgomery stepped between the two, telling Calkins he needed to talk to the Mayor, not to Ms. Pierce. Someone told someone else to ‘shut up’ “). Sun then put Calkins on paid leave, and four months later fired him for berating city staff. The ex-chief is appealing his dismissal, and a civil-service decision is due shortly.

Sun was supported by those who said Calkins had abused his power. But for Montgomery and other city employees, it was the first tip-off that the mayor would do things his way. As eight of the city’s nine police officers would later say in a statement of no confidence after the mayor interfered with one of their investigations, “It is very clear that Mayor Sun is a profound believer in the ‘my way or the highway’ theory.”

That was what city Building Inspector Roger Smith felt, too, after the mayor ordered him, without explanation, to stop issuing permits. Smith said he felt harassed and went on medical leave, and has yet to return. Shortly before Sun took office, Public Works/Community Development Director Jay Bennett resigned, saying Sun had promised to fire him anyway. He has yet to be replaced.

In February, Sun ordered the police department to halt an investigation into who had sent a letter to the city containing court copies of the murder conviction of councilmember Hulsey. At the time, Hulsey and Sun were at loggerheads over the validity of Sun’s war medals. Sun was worried that the name of the alleged letter-sender would leak out. She was one of his supporters, and on her anonymous letter had used a fake return address—the home of Rich Hildreth, the incumbent mayor Sun defeated—making it appear that Hildreth had exposed Hulsey’s record.

The court papers detailed how Hulsey, a Vietnam veteran, had stabbed his wife to death in Whatcom County in 1978. He pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity, was convicted of second-degree murder, sentenced to 20 years, and paroled after eight. The conviction was unknown to voters, who have elected Hulsey twice since 2007

Sun, according to sworn police testimony, told his officers to tell the alleged sender she was not being investigated, and said they shouldn’t pursue an investigation because the woman was schizophrenic. The mayor gathered three of the officers in a training room and, using a whiteboard for illustration, lectured them about schizophrenia, they said, noting he had once taken a class on the topic at the University of Tokyo given by a Nobel Prize–winning instructor. He also told the officers, according to acting chief Lt. Ed Massey, that they were violating the woman’s constitutional rights. She could sue the city for $5 million for such violations, and he would be a witness against the police in such a lawsuit, Sun said. Massey refused to comply with the mayor’s orders, and notified the State Patrol and Postal Service inspectors. They subsequently determined that no crime had been committed by the sender.

Word of the letter leaked, however, and the 64-year-old Hulsey—who plans to retire after this term—spoke for the first time of the murder at a council meeting, telling the public and reporters he was likely suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder when the slaying occurred. He later told CNN that in 1978 he was drinking a fifth of whiskey daily and, awakening one morning, found his wife dead with his knife in her chest. He called police and said, “I think I just killed my wife, I don’t know.”

Effectively, Sun’s letter-writing supporter had outed Hulsey, and Sun had forced Hulsey to apologize for questioning his war medals after the Auburn Reporter printed supporting evidence confirming he’d earned the medals. (Seattle Weekly has obtained additional documents corroborating Sun’s claims.) “I am not a liar,” an emotional Sun told an audience of 75 who gathered to hear his nearly hour-long medal speech at a local gym. “I’ve been to hell and back.”

Meanwhile, the war went on at city hall. In a sworn statement, City Engineer Jim Morgan says that, though on the campaign trail Sun had praised him as “an asset,” Sun told him at their first sit-down meeting, “You don’t know shit.” The mayor was so aggressive and profane, Morgan says, that he came to work with knots in his stomach, and eventually resigned (the job remains vacant). Also departing was Linda Morris, fired by Sun as Community Services Director. She has not been permanently replaced.

Sun’s scorched-earth takeover made headlines, and the townsfolk took notice. “Used to be, the biggest news in Pacific was some kid ran his horse down the main street and got a speeding ticket,” says Fancher. But today’s headlines aren’t unprecedented.

After its historic farmlands were overrun by real-estate developments in the 1970s thanks to the creation of a new valley-wide sewage system, a growing Pacific notched one of its first town scandals: the 1975 resignation of two-term mayor Jack Johnson in the wake of several police-brutality incidents. Police Chief Ron Earwood resigned later that year, saying he was taking a better job elsewhere. And in 2008, then-Chief John Tucker, wearing a souvenir Chicago Police Department T-shirt that recalled the 1968 Democratic convention head-busting with the emblazoned words, “We Kicked Your Father’s Ass, Now It’s Your Turn,” was stopped for drunk driving in Bonney Lake. He beat the rap in 2009, but has been a controversial figure since, earning the first pink slip handed out by Sun this year.

In March, Sun decided to create his “Control Room,” telling employees he was taking over city hall’s conference space for his clean-up-corruption mission and ordering a crew to throw things out. Associate Planner Paula Wiech had used the space for Planning Commission and Park Board meetings. In a sworn statement, she says she determined that posters and maps had been haphazardly tossed out, some landing in a Dumpster, and that irreplaceable historical documents possibly went missing.

At the same time, Sun told Wiech he was changing her job duties, and later ordered her not to get involved in public-works and environmental issues. It was the start of another feud similar to those Sun was already carrying on with the police department, the city clerk, and the city council.

The resignations continued in April. Finance Director Pierce bailed, citing a hostile work environment. Resentment against the mayor was boiling over, resulting in the distribution around town of a 10-page pamphlet asking, in large bold type, “Who Is The Real Cy Sun?” Written anonymously, it was sent to newspapers and TV stations, which did not report the undocumented claims. The pamphlet recounted the city firings and resignations; allegations about Sun’s messy divorce from his first wife 40 years ago; and a series of alleged lies Sun had supposedly told neighbors in the town of Echo, Ore., where he operated a horse ranch. Besides the Kissinger and Don Ho allegations, the pamphlet asserted that Sun had told people he was the only farrier allowed to shoe Triple Crown winner Secretariat. The material included alleged pictures of the ranch, showing a small, inactive farm rather than the large stables he allegedly claimed to operate.

Sun called the pamphlet a fabrication, and immediately ordered his police department to determine who was spreading lies about him. It was dubbed the case of the “Echo Papers,” according to police documents. In his order to Acting Chief Massey, Sun said police should undertake a “discreet” probe of who had trespassed on his Oregon property. He said a polygraph test should be given to whomever was behind the “conspiracy,” and that the local sheriff’s department of Umatilla County, Ore., should also be investigated, “if they were involved.” Massey’s finished report “shall be comprehensive and complete, and could be submitted in a Court of Law,” Sun wrote in his two-page order.

Massey balked at undertaking what amounted to a secret investigation of the mayor’s political enemies. Later that day, the lieutenant received a second letter from Sun: “Effective 3 p.m. of the above date, my confidence in you as Acting Chief of Police was a misjudgment. Therefore, you are immediately removed from Acting Chief of Police and shall have no command authority.”

The next day, Massey and seven other officers signed a letter of no confidence against Sun, citing his interference in investigations and failure to name a permanent chief, as well as his demoralizing method of dealing with officers. The letter was given to the city council, which then issued its own no-confidence vote, citing the mayor’s “outright misinformation and lies,” his elimination of every Pacific department head, and his bungling of several city projects, including one that could cost the city $700,000 in forfeited payments. Turmoil in the police department was also contributing to a rise in crime, new statistics indicated.

One department member, Sgt. Jim Pickett, did not sign the cops’ no-confidence letter. By the end of the day, he was Sun’s new Acting Chief of Police.

In May, Sun issued his first, and to date only, monthly newsletter, claiming his job eliminations had saved the city more than $222,000. (He has fired or forced out about a dozen of the city’s 20 full-time staffers.) His reward, he wrote, was “a unanimous vote of NO CONFIDENCE!

“Give me some slack!” he said in the letter to his constituents. The situation has caused “an agony, shame, and depression that penetrated both my wife (deeply) and I. I’m worried about my wife’s mental health.” How long, he wondered, “am I able to endure? Because I’m 82 and the mental (stress caused by all the political intrigues) condition of my wife, I have my reservations.”

As for all those empty departmental positions, he says, “From what you’ve read [in the news media], you’re thinking ‘Who is the Public Works/Community Development Director and Engineer for all the on-going projects?’ The answer is: ‘I am!’ Your $750 a month mayor —for now!”

Sun then devised a plan to solve the backlog of building-permit applications and other city business by hiring consultants, including political backer and three-term ex-mayor Howard Erickson, as building and code-enforcement officer. That move was aborted when the Teamsters Union said such a hire would violate the city’s labor contract. It turned out that both Sun and Erickson were signing off on building permits, though neither was authorized to do so.

Hearing this, City Clerk Montgomery notified the city attorney and the city’s insurance carrier. The attorney, Ken Luce, informed Sun that his actions were unlawful and said the permits he signed were invalid.

Montgomery says she then discovered that Sun had taken Public Works files to his home. After being brushed off by Sun when she questioned the file removal, Montgomery filed a whistle-blower’s complaint against the mayor, accusing him of a litany of violations, including removing, destroying, and attempting to alter city records.

Sun called Acting Chief Pickett and said he was going to fire Montgomery—even though such an act could been seen as retaliation against a declared whistle-blower—and ordered the chief to deliver her a dismissal notice. Attorney Luce told the mayor and chief not to do so. Sun did what he thought was the next best thing: He had a lock placed on Montgomery’s city-hall door so she couldn’t enter. Luce then had police cut off the lock. Officers also stood watch during the week to assist her. Montgomery subsequently went on medical leave.

That was too much even for Chief Pickett. In a resignation letter, he told Sun, “I sense that I am being drawn toward a pit of unethical behavior.” He also recounted how he’d informed Sun that a councilmember had claimed a “possible federal investigation” was looming “into questions related to your identity.” According to a rumor among Sun’s detractors, there are questions about his true name and birth date, though SW has obtained his birth certificate from Hawaii (shades of Obama), which show he was born Cy Sun on Jan. 26, 1930 at 4 a.m. He also goes by Herbert Cy Sun, which he says is a first name he picked out just because he liked it.

Sun wanted to know more about the ID probe and was upset that Pickett wouldn’t provide details, including the identity of the federal agent. Sun told Pickett he no longer trusted him, and Pickett then stepped down. The third chief to resign within six months, his departure has left the police department, to this day, with no leader.

In July, Pacific’s insurance carrier notified Sun and the council that because of administrative vacancies and questions about the city’s financial condition, the carrier would cancel Pacific’s insurance coverage on Dec. 31. That situation remains unresolved, and further erosion of Pacific’s fiduciary stability could lead to additional problems, including bankruptcy and the dissolution of the city, councilmembers and others warn.

That erosion of confidence deepened as a grandstanding Sun forced a showdown with police and the city clerk by getting arrested trying to enter the clerk’s locked offices, then firing the police officers who took him into custody. The July 19 arrest—Sun, a locksmith at his side, charging into police tape and the arms of officers, then scolding them for hurting him as they applied handcuffs—was captured on video that was picked up in news reports around the nation. Police had been told by attorney Luce to prevent the mayor from entering the offices, as he was now under preliminary investigation—at the council’s request—by the King County Sheriff’s Office for possible destruction of public records.

Sun thinks it’s his police department that should be investigated, tending to view police troubles as corruption. “My arrest was a corruption,” he says. “How can I be prevented from entering offices in my own city hall?” It’s a question that continues to hang in the air: There is no conclusive evidence he has destroyed any records, and the advice given to police to arrest Sun was arguably as much political as legal.

Having already tried to fire four cops (the city attorney told them to return to work), Sun then fired Montgomery, saying she failed to follow his orders. He also blamed her for “causing me to be arrested by Pacific Police [and] causing damaging nationwide news media coverage for the City of Pacific.” He told her in a letter that should she refuse to attend a Loudermill hearing—a kind of show-cause hearing at which government employees defend their actions, and which in this case would be presided over by Sun himself—”your DISCHARGE is final.” When Montgomery showed up for her hearing, however, she found the door locked and saw Sun running out another door, according to her sworn statement.

Montgomery later filed a $2.2 million damage claim with the city for wrongful discharge. Loudermills were also required for the four fired officers; Sun, however, called an immediate end to the hearings the moment the four officers’ attorneys began to speak, claiming, incorrectly, that they were not allowed to talk. The mayor said he considered the officers’ actions “mutiny and anarchy,” and wrote the governor and attorney general, asking them to send help. They did not respond.

Wiech, the associate planner, also filed a whistle-blower’s complaint against Sun in August, claiming he had destroyed records and improperly signed permit applications. “He suggested taking grant money earmarked for other purposes, and lying about what we actually used them for,” she said in her complaint. She also said the mayor told her that his “phone was bugged, but the FBI was on his side.”

As if the city-hall battles weren’t troublesome enough, the mayor was suddenly hauled into civil court by a 57-year-old woman who claimed he’d molested her more than 40 years earlier. Kathy Carbaugh, now of California, lived with her family next door to Sun and his family in Fife Heights near Tacoma when he began sexually abusing her at age 14 for a year and a half, she claimed.

It wasn’t a new accusation: Sun, who was never criminally charged, had been sued by her family in 1970 for $10,000 in damages for the humiliation he’d allegedly caused, but they lost. Sun countersued for defamation—noting that the family had also claimed he’d raped Carbaugh’s mother—and won.

Sun insists the charges are as untrue today as they were proven to be decades ago. After he won his countersuit, Sun adds, Carbaugh’s father came to him pleading that he was unable to pay the $30,000 judgment, and Sun agreed to settle for $1.

He calls the suit politically motivated, and wonders how he can be sued over the same issue again. And Sun has a point: On Aug. 30, attorneys for Carbaugh voluntarily dismissed the suit “without fees or costs to any party.” The suit was dropped after attorneys learned it effectively sought the same relief as the family’s 1970 lawsuit, “and you can’t sue someone twice for the same reason,” said an attorney familiar with the case, who asked not to be named.

In a statement released to SW, Carbaugh said: “When I was a young girl, I was unable to tell the full truth of what happened to me because I was scared and did not want my parents to feel guilty for what happened to me. The law is still evolving to protect people like me, but I hope I have given a voice to other survivors of child sexual abuse who have not yet come forward.”

Meanwhile, a week earlier, the recall was moving forward. At an Aug. 23 press conference on the city-hall lawn, Thomson, chair of the Committee to Recall Cy Sun, unveiled the statement of charges in a 200-page book. Thomson then drove to the King County Elections office to file charges, claiming Sun was guilty of malfeasance and violating his oath of office. The charges include claims from a city worker who reported that Sun had said he was “conducting surveillance” on the city clerk’s home, and that Sun had photos in his office showing the clerk and another city employee outside the clerk’s residence.

If a judge’s review determines there is sufficient cause for a recall vote, petitioners have six months to gather about 400 signatures to qualify the measure for the ballot, although Thomson hopes the issue will come before voters in the November general election. “We think it can be done by then,” he says. “People are excited to sign.” The drive will cost at least $15,000, most of it covered by local donations.

Cline, the council candidate and Sun supporter, thinks the recall will prove just how strong the mayor is. “He hasn’t quit yet, when lesser men would have,” says Cline.

After the Aug. 27 council meeting, the second time that Sun had handed off his presiding duties due to his chronic tinnitus, councilmember Joshua Putnam posted his thoughts on Facebook. He wished that, rather than being forced by a majority council vote to turn over the meeting to mayor pro tem Jones, Sun could have been allowed to stay and be assisted by a councilmember.

“We really could have used the Mayor’s presence, at least to hear if he would in fact sign various agreements he was being authorized to sign,” Putnam said. “I understand there’s plenty of opposition to the Mayor and what he’s done to the City so far this year, and there’s well-grounded fear the City may collapse at the end of the year when our insurance runs out. But the fact is, whether you like him or not, Mayor Sun is the Mayor at the moment . . . I don’t see the harm in letting him delegate administration of Council meetings to a Councilmember.”

After Sun left, city attorney Luce suggested the council seek a court order forcing the mayor to fill city management positions. Luce also said that police and civil-service staff vacancies could be advertised immediately.

With the sounds of tintinnabulation and audience laughter ringing in his ears, Sun was getting out of his car at his home a few minutes after leaving the meeting that night when SW caught up with him.

“They were very, very vindictive; they’re mean, they have no respect for human rights. Savages,” Sun said, his voice wavering and his eyes tearing up. He unloaded papers from his Volkswagen bug, one of three he owns and tinkers with. “The audience, the council, they want to see me go down.”

A few blocks from city hall down Milwaukee Boulevard, Sun sat at his dining table in the modest, well-kept home and told his wife Barbara he got a “very bad” reception tonight. “The council voted that I will handle the meeting. And you know if I handle the meeting I can’t hear good, I’ll make a fool out of myself, and I handed it over to the mayor pro tem, and I left. You see, what the council wanted to do was to degrade me. Maybe I should take off my clothes and let them see all my scars and my operations and all my pockmarks from the shrapnel.”

“They’re trying to force you out,” Barbara said. “But it isn’t the whole community.”

Sun wasn’t sure. He’s heard some people still doubt his war medals, and remembers the stranger who walked up to him in February and shouted, “You’re a disgrace!” At the table, he pulled out a letter he’d recently sent to U.S. Senator Daniel Akaka of Hawaii, asking for help documenting his Distinguished Service Cross, for which he doesn’t have papers. In the letter, he laments to Akaka: “It won’t be long, I’ll may be [sic] recalled and be moving back to Oregon, in shame, and that’s a miserable way to live out my life.”

Thomson’s 200-page recall document was sitting near Sun on the table. “I don’t want to do anything about it,” the mayor said, waving his hand. “I’m not going to court and drag it out. I want the recall [vote] to occur.”

He paused and his wife sat quietly as he weighed his thoughts. “I got so much language in my mind that sometimes I got to sift things out before I make a statement,” Sun said, tapping on his head. The ringing compounds that: “Sometimes it’s so loud, I get dizzy,” he says.

The recall charges are only allegations, Sun concluded. “They’re not proof of anything.”

He leaned back and began talking about an upcoming Army reunion, where he planned to meet with two of the three other surviving members of his Korea regiment. “Here’s the way I think. You can see by the way I thought in combat. I never make a move until I know how to make it. I put all the forces together and I take the least resistant route, and do the best I can, the same as I do all my life.

“I never backed down,” he added. “You take a guy who runs up the hill and kills everybody in combat. You think he’s going to give up? I’m going to let them say all they want to say, and let them do all they want to do, and I’m going to let the people decide.”

What the hell—it’s how he got elected.