On the battlefield of civil rights, Ed Pratt liked to say, learn to duck. Supporters think you don’t do enough, and opponents say you’ve gone too far. It’s life in a crossfire, and the coolly imposing, mustachioed director of the Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle was living it in 1960s Seattle, where Pratt had become one of the predominately white city’s most influential and outspoken black leaders, admired for his sense of humor and ability to find the high middle ground.

By the end of the decade, a year after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., the 38-year-old Pratt pushed hard for school and workplace desegregation, the de-ghettoizing of neighborhoods, and an end to police harassment. He attracted wide, biracial support among moderates. But he’d also united the races in another campaign: Dissenters black and white seemed to be lining up to do him in.

They sent angry letters, left intimidating messages, and got up at public meetings to threaten his life. Pratt’s white secretary, who took a lot of the messages, thought some of her boss’ fellow African-Americans were the most resentful—the more militant ones sometimes publicly vowed to “eliminate” him. His good work became less important, and he began to worry about his demise, his secretary would later tell investigators.

It didn’t help matters that Pratt was also having a secret affair with the secretary (she has asked not to be named here, out of fear for her safety), and had recently gotten up the nerve to ask his wife of 13 years, Bettye, for a divorce. Distraught, Bettye, a dry alcoholic, was drinking again and threatening to kill him if he left her. Ed Pratt’s nerves were jangled; he was worn down by conflict at work and home. He’d made up his mind to take a job elsewhere, possibly at Boeing, maybe even overseas. As the girlfriend remembers it, he vowed to marry her and move somewhere out of shouting, if not shooting, distance.

Pratt was supposed to meet his secretary/girlfriend for dinner at her apartment on the night of January 26, 1969. But there’d been a rare heavy Seattle snow that Sunday, and he called her around 8 p.m. to say he’d see her the next day instead. Pratt settled in at home for the night, sitting in his favorite chair, clipping race-related stories from newspapers, as he often did, while watching TV.

Bettye was in a bedroom putting their 5-year-old daughter Miriam down for the night. She and Ed were both Southerners who’d grown up poor in the 1930s—he in Miami, she in Texas. They met in their early 20s while attending Atlanta University, and moved to Seattle after their marriage in 1956, when he became the Urban League’s community-relations head. He was named executive director in 1961.

The attractive Bettye, a social worker and sometime alcoholism counselor, supported and worried about her husband. She’d been anxious since she’d received a threatening phone call after Mississippi civil-rights leader Medgar Evers was assassinated in his driveway by a Ku Klux Klan member in 1963. “If Ed doesn’t shut up,” said the female caller, “he’ll end up like Medgar.”

Hardly an hour had passed when Ed Pratt heard snowballs hitting the sides of his Shoreline rambler on First Avenue Northeast. The Richmond Highlands neighborhood was white as the outdoors that evening. Pratt, in his slippers, padded to the front door and poked his head out into the cold night. Seeing figures under his driveway’s carport, he said, “Who’s there?” A shotgun suddenly exploded, the slug tearing through Ed Pratt’s mouth and lodging in his neck after glancing off bone, severing his spine. He crumpled to the carpet as Bettye, who’d been looking out the bedroom window, saw the red muzzle flash and shouted, “They’ve got a rifle!” By then, her husband was already dead.

The figures disappeared into the night. Neighbors who heard the shot saw two young men hop into what some guessed was a 1968 Buick Skylark, driven by a third man. “They looked like kids,” said a witness. “It was the way they ran—the gait.” No one got a good look at the suspects. Some thought they were white, others said they were black.

In death, Pratt got the undivided attention of his city and its police, suddenly dealing with a Southern-style racial assassination. Words of praise and grief flowed from local and national leaders, including President Richard Nixon, who wrote Bettye Pratt a note of condolence. The rarity of the murder of a black leader in a northern white community moved Nixon to dub Pratt the MLK of the Northwest.

At Pratt’s crowded funeral at St. Mark’s Cathedral on Capitol Hill, his friend and St. Mark’s dean, the Very Reverend John C. Leffler, recalled Pratt’s ghetto childhood and wondered if “he had a subconscious knowledge that he had to pack a lot of work into a short time.” Whitney Young, national Urban League director, said, “I sense some shame that this could happen here . . . They—the killers—probably came from this environment.”

City, county, and federal investigators pored over the scant evidence: the 12-gauge slug taken from Pratt’s body, the tire tracks and the footprints in the snow. Over the next few months they would question hundreds of witnesses and suspects. Aides to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover and U.S. Attorney General John Mitchell were involved on a daily basis, in part secretly hoping to keep a lid on racial tensions. In a teletype message sent to Hoover and relayed to the Seattle FBI office two days after the shooting, Mitchell wrote, “It has come to my attention that certain black groups are circulating a story to the effect that the death of Pratt was caused by White racists. Does your bureau have any information to the contrary, and, if so, is there any way it might be publicized through local police or otherwise?”

King County’s plainspoken sheriff, Jack Porter, replied by saying what most people were thinking: “I can see no motivation for the killing other than politics or race.” Forensically, he added, all it took was a coward’s close-up shot. “This wouldn’t require a great deal of professionalism.”

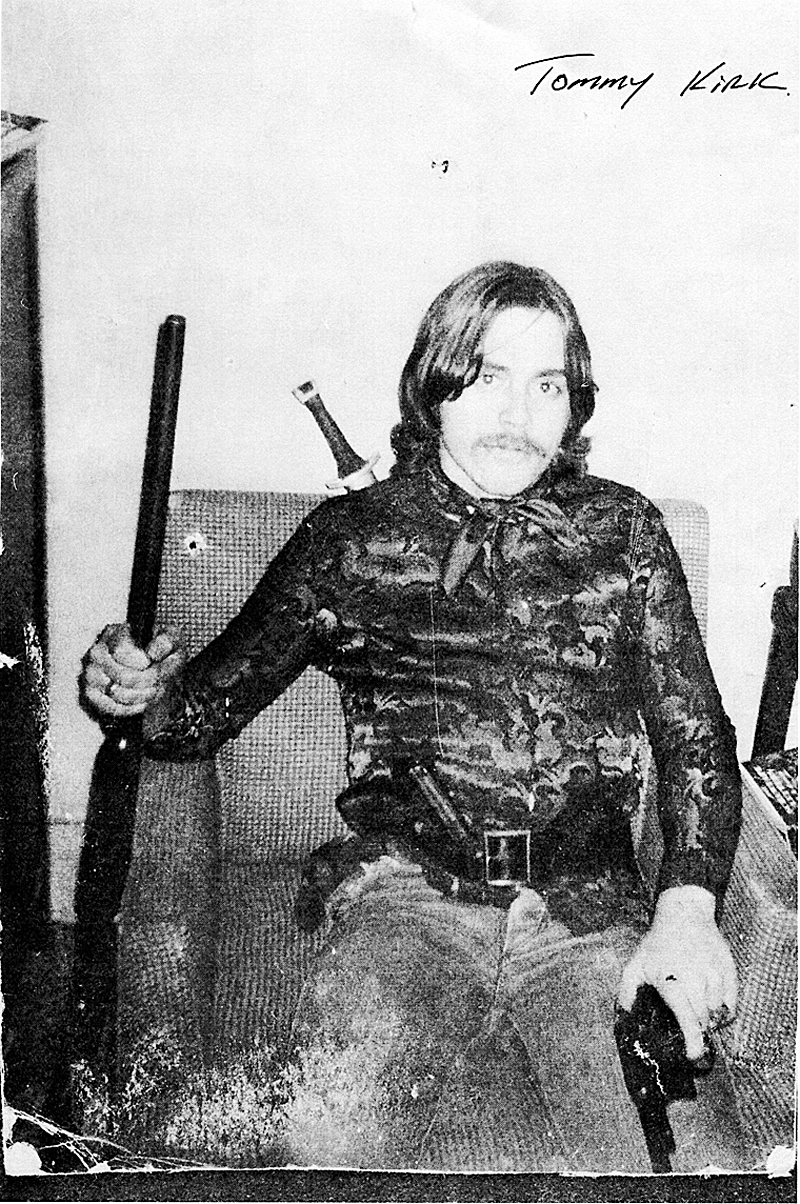

The investigation went nowhere, despite a $10,000 reward, and no one was ever arrested or charged with the crime. Still, Porter’s department, the lead agency in the case, continues to probe Edwin T. Pratt’s death today, 42 years later. It officially remains unsolved, bound in six weighty case files stored in a cold-case library at the Regional Justice Center in Kent. The case went cold for 25 years, then suddenly jumped back to life in 1995 when the Seattle Post-Intelligencer broke new ground, quoting witnesses who said two white men had committed the crime and bragged about it. They were the shooter, Tommy Kirk, 21, a violent street thug, and his accomplice at the Pratt home, Texas Barton Gray, 49, an armed drug dealer. A third person, unnamed, drove the getaway car. Furthermore, someone likely paid for the hit. But who? And what was the motive?

There are now some answers: The case appears to have reached its end, and in the view of some may be solved. King County Sheriff Sue Rahr recently allowed Seattle Weekly access to previously undisclosed information, which the paper had been seeking through public-records requests for five years. Based on documents and interviews with cold-case detectives and two witnesses who were with the three-man hit team after the murder, Seattle Weekly has confirmed that Kirk, described as a psychopathic, trigger-happy drug dealer, fired the shot that killed Pratt. Gray, a longtime drug dealer and gun peddler, was his lookout in the carport that night. Detectives and the witnesses now also have identified the third man, Michael Lee Jordan, then 22, a small-time criminal who drove the getaway car. All were white, all are dead—and may have collectively been paid as much as $25,000.

Cold-case detectives also think a rabble-rousing black contractor named Henry Roney, who can be circumstantially connected to Tommy Kirk through a supposed association with the Black Panthers, is most likely the man who paid for the shooting. He was questioned only days after Pratt’s 1969 death, and, according to confidential records, was considered a top suspect even back then by county and FBI investigators. “No one had a greater motive,” says county detective Scott Tompkins, who has been working the case over the past five years. “When you look at the evidence, it’s very compelling.”

But it’s no slam dunk: Roney, who died 15 years ago, denied any role in the slaying, records show, and his former attorney says Roney is wrongly accused. There’s an alternate version of the story as well. It comes from the former wife of Jordan, the getaway driver. Danella Jordan was with her husband, Kirk, and Gray just hours after the Pratt shooting. In her first newspaper interview, Jordan tells Seattle Weekly she thinks detectives have solved the case but don’t know it.

There’s no shadowy, behind-the-scenes figure, she claims. Kirk was a wild man and racist who had vowed to her and others to kill “a ‘rich nigger.’ ” Seattle’s historic unsolved assassination “was a monumental hate crime,” she says, committed by one man. At least one public official, a King County Council member who has followed the case from the night of the shooting, sides with her.

In the words of Pratt’s secretary, “Uncle Tom” and “house nigger” were two phrases Pratt was accustomed to seeing and hearing in messages and public meetings. In 1969, she told investigators that he regularly received letters saying, in effect, “You’ve gone too far, black boy, and we’ll get you,” while others accused him of being “white inside.” She wondered how angry they’d be if they knew he was fooling around with a white woman.

Seattle in those days was struggling with epic change in race relations, and still using the word Negro in unguarded conversation. An especially memorable racial litmus test was unfolding back then at the University of Washington, where white football coach Jim Owens caused an uproar in 1969, suspending four of his black players for refusing to pledge 100 percent loyalty to him; they felt he meted out harsher discipline to black players than to white. But football fans, mostly white, backed Owens, giving him a booming round of applause the next time he entered Husky Stadium. The issue festered for years, however, and he retired in 1974. It wasn’t until 2003, at a homecoming game, that the aging coach appeared on the field at halftime, took the microphone, and issued a heartfelt apology to his players for any pain he had caused. Most of the 72,000 fans responded with a standing ovation.

The Queen City, as it was then known, was a low-rise, inbred, industrial municipality where people communicated by landline and mailed letters pecked out on typewriters. It was a backward time as well for minorities, who sought equality in housing and jobs and balance in the city’s de facto segregated schools.

Pratt’s Urban League, like the NAACP, picked its moments carefully. In education, Pratt saw an opportunity in the 1960s’ Triad Plan, a three-phase effort to reorganize Seattle’s elementary schools—much to the dismay of some white parents. Others weren’t happy about his goal to “build ghetto political power,” as he put it, “possible only through complete integration of all minorities into American society.” Whites would have to learn to share power, Pratt said, “instead of withdrawing whenever the balance of power shifts against them.”

Much of this angst took place while Pratt was dealing with his own interracial conflicts. He’d been having an affair with his white girlfriend since she’d taken the job as Urban League secretary in 1967. He eventually promised to leave his wife—and did for one stretch in 1968, moving from Shoreline to an apartment on Queen Anne for two months. But he was torn by his marital and parental responsibilities. He and the girlfriend ran into his wife at a north Seattle movie theater, causing a scene and later prompting an angry phone call from Bettye to the girlfriend, informing her she’d just become part of one big, messy divorce. Pratt later moved back home, and the affair cooled.

Pratt, however, grew jealous and spied on the secretary when she began dating a traveling shoe salesman. That prompted him to ask Bettye again for a divorce in 1969. The next day, she gave her frustrated answer: If he left her, she’d kill him. She later said she didn’t mean it. (Bettye, who moved away after her husband’s murder, remarried in 1972 to a black pastor and lived in St. Louis. She died in 1976, at age 47.)

Pratt, though, was ready for a lifestyle change, the girlfriend told the FBI in a 1969 interview. He was finally prepared to quit the Urban League and marry her. He’d just turned down a tempting offer to become Westchester County’s (N.Y.) Urban League executive director, and told the girlfriend he might take advantage of his front-office connections to land a white-collar job at Boeing. They had dinner at her apartment the night before he was killed, and would have been together there again that fateful Sunday—perhaps changing the course of tragic events—had it not snowed.

When FBI agents came to see the secretary two days after the shooting, she told them about the affair, but felt it had nothing to do with Pratt’s death. Agents later investigated a relative of the secretary, a state trooper who might not have appreciated it when the secretary told her family she was planning to marry a black man. But the trooper was later cleared.

Actually, the secretary told the agents, from her experience, “More bitterness and hate for Mr. Pratt emanated from the black community in Seattle than from the white.” His moderate, nonviolent approach was seen by some—militants especially—as moving too slowly and kowtowing to white powerbrokers. One man, the secretary recalled, stood up at a small gathering to discuss desegregating Seattle schools, and said to Pratt he knew “how to take care of you—to eliminate you.”

It was clearly meant as a death threat, the secretary said.

That was in December 1968, a month before Pratt was killed. After the meeting, Pratt told his secretary he might be becoming paranoid. It was, she recalled, the same thing he’d said after two earlier meetings. The danger of his work was getting to him, and it was a volatile time, with marchers demonstrating against war, racism, and police brutality.

In particular, black contractors and workers were demanding job equality. White employers and government officials were slow to follow a new federal mandate—backed by Assistant U.S. Labor Secretary and former Washington lieutenant governor candidate Arthur Fletcher, the African-American “father of affirmative action”—that required one in five jobs at government construction projects to go to minorities. Black workers began demonstrating at job sites, sometimes destroying property and clashing with white counterprotesters.

It was divisive but effective, and as the movement progressed in 1969, work was stopped on virtually every major, federally funded construction site in Seattle, including projects at the University of Washington and Sea-Tac Airport. At one point that year, about 3,000 people, mostly white, marched to Seattle Center in support of efforts by the black Central Contractors Association to increase minority employment.

Pratt had been sympathetic to the cause, and in a speech given just days before his death, said there were “2,200 firms who ought to be hiring at least two unemployed black persons for every 100 persons on the payroll.” Yet militants were critical and wanted to see him banging some heads.

Black contractor Henry “Hank” Roney was among Pratt’s detractors. As he’d later tell FBI investigators, he didn’t respect Pratt, complaining he was too “white inside.” Roney, referred to in the newspapers at the time as a “Negro builder,” was head of the Northwest chapter of the National Association of Minority Contractors. Born in Texas, he was orphaned at age 3 and raised by his aunt. He was a construction worker who had become a successful contractor here; his was one of the few black families at the time living on Mercer Island.

Roney considered himself a uniter, forming a coalition of blacks and whites he called The Group, which met to discuss racial issues. But he also was an angry man, telling Seattle city leaders that police were acting like Nazi storm troopers in the Central District, and should withdraw. He told City Hall not to listen to clergy members or black leaders like Pratt, whom he considered Uncle Toms.

Sources back in 1969 told the FBI that Roney had close ties to the Panthers, and a 1968 Seattle Times story reported that Roney was inside Panthers headquarters when police raided it and arrested two Panthers for possession of stolen property. The story does not indicate Roney was arrested. A newer source told a cold-case detective in 1994 that assassin Kirk, who bought and sold drugs and guns in the Central District, associated with some of the Panthers, and could have met Roney through them. A 1995 FBI report quotes an associate of Kirk’s as saying “Kirk was superprejudiced about blacks and fearful of being killed by blacks. He sold dope to them, including the Black Panthers.”

Formed here in 1968, the Panthers dressed in a uniform of black berets and leather jackets, often toting rifles in public and advocating armed self-defense against “the pigs” during their 10-year Seattle existence. While the Panthers were in trouble with the law, they also won community support for standing up to rampant racial profiling and police brutality in the CD.

It was a period when historic corruption—police shakedowns, beatings, and payoffs—from Seattle’s “tolerance policy” days was about to be exposed by grand jury investigations in the early 1970s. The city was also wracked by a series of violent protests and police shootings in black neighborhoods, including the controversial killing of Vietnam veteran Larry Ward, who had been recruited by a police informant to bomb a white-owned real-estate office at 23rd Avenue and Union Street. He was shot by police when he fled after trying to light a fuse. They had been expecting another suspect, a Panther member, for whom non-member Ward had filled in at the last minute.

The FBI source in 1969 “said that a black contractor was involved” with the Panthers, according to records, and was angry that Pratt had opposed the awarding of a federal contract to the builder. The “black contractor, who had political ties, also knows the Black Panthers and the Panthers went to Kirk for the hit on Pratt,” the source said. Agents weren’t sure whether the source was reliable, but the details seemed to fit with other information they had received, including one witness’ sighting of Kirk, not long before the murder, with several well-dressed black men.

Historian Trevor Griffey, project coordinator for the Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project at the University of Washington (and a former Seattle Weekly contributor), suspects that Roney was behind Pratt’s death. Griffey has studied the case and compiled his own collection of FBI files. Also on his suspect list is Keve Bray, who at the time was publisher of the militant Afro-American Journal.

It turns out that Bray, like Roney, was on the original county and FBI lists of top suspects, and is still considered a suspect today by cold-case detectives. Bray and Roney were in fact rivals, says Griffey, and both took to beating up people, sometimes each other.

“Bray had Roney beaten to a pulp by a guy nicknamed ‘Bonecrusher’ in early September 1969, after Roney tried to take control of the Central Contractors Association,” Griffey says. Among those who Roney had beaten up, says Griffey, was Tyree Scott, a leader of the CCA, in a struggle for control of the movement.

A schoolteacher, activist, and sometimes playwright, Bray was often accused of inciting violence in his Journal writings, and at one point was suspected of trying to bomb the car of Seattle Mayor Dorm Braman, who opposed an open-housing initiative that was subsequently rejected by voters. Bray moved to Denver in 1971 and, as a Black Muslim, changed his named to Keve X. He was murdered there the next year, shot twice when he answered a knock on his door. Police investigated the case as a possible link to the Pratt murder, but it too went cold. In 1981, however, a man named Daniel Karlem walked into a Denver police station carrying his lunchbox and confessed to the murder, which involved a personal dispute within the Denver Black Muslim community.

But the case against Bray as the Pratt murder-mastermind is as circumstantial as the case against Roney, and there’s no evidence either knew the gunman, Kirk. Though cold-case detectives feel their evidence and witness claims point strongly to Roney, his onetime attorney, Peter Mair, says it sounds unlikely. “I guess I’d be shocked if that were true, from what I knew about him,” says Mair, a Seattle criminal-defense attorney. “He was a community guy, he got whites and blacks together. He was a hardworking, decent guy, and I don’t believe he was involved.”

King County Council member Larry Gossett also has his doubts. Gossett has long campaigned to have the Pratt case opened to the public, and was heartened to hear more details have been released. But “the Panthers,” says Gossett, “weren’t opposed to Pratt.”

He should know: As a young Black Power movement leader, Gossett was closely allied with the Panthers and grew up with the local chapter’s founders: brothers Aaron and Elmer Dixon and several others. As a community activist, he went to jail with them in the 1960s after being arrested during demonstrations (his council office atop the county courthouse building, where the old city jail used to be, is in the approximate location of the cell where he was held).

Told of the various scenarios of Pratt’s murder, Gossett felt there was no clear link between Kirk and Roney, or for that matter Kirk and Bray, whom he disliked. “Bray used to make up stories about me and Rev. Sam McKinney and others, saying we sold drugs to children,” he says with a small laugh. As for the Panthers, they had no motive to get behind the murder of one of their community leaders, Gossett says. “It’s my impression the Panthers generally supported Pratt, and wouldn’t have wanted to have him killed.”

He also doubts that Roney, whom he knew personally, was a friend of the Panthers. “Hank’s philosophy and orientation was so radically different than theirs—there was nothing that would give them common ground. Hank got along with people, though he caused problems in the CCA [the contractors’ group] and was one of those who beat up Tyree Scott. But I cannot envision any proof that Roney was close to the Panthers. I’m pretty sure he wasn’t close, because I was close to them at that time.”

There was at least one more viable suspect as the man behind the Pratt killing: a white ex-con named Kenneth Moen. He became a prime suspect in 1969 after witnesses told investigators that Moen had claimed he “got Pratt,” something he had promised to do earlier. His reputed motive was revenge: A white friend of Moen’s had been killed by a black man, and Moen supposedly thought killing Pratt would even the score.

Witnesses described Moen after the shooting as frightened, drunk, and hiding out in Snohomish County, vowing not to be taken alive. His probation officer felt Moen was capable of such a murder. He’d committed armed robberies and once escaped from jail in Idaho. He also at times stayed at a home near Pratt’s, and was known to have a shotgun. Moen also revealed some knowledge about little-known evidence from the crime scene, telling witnesses his one big mistake was wearing pointy-toed shoes. The killers, according to evidence photos, wore such shoes.

Then again, he might have picked up that detail from some media report. After a long manhunt, Moen was taken into custody, where he agreed to take a polygraph test. Asked if he’d killed Pratt or had been involved in any way in a conspiracy to kill him, he answered no.

The lie detector showed no deception in his answer, according to records. Moen was 71 when he died in 2005.

But if not these men, then who? The widow of the getaway driver might know; she’s one of the last people alive who can tell the story.

Forget trying to link Tommy Kirk to black contractors or a murder-for-hire scheme, Danella Jordan says. Tommy did it for white people.

Jordan never heard Tommy Kirk mention the names Roney, Bray, or Moen. But he did mention Ed Pratt.

“Tommy had heard about Pratt,” says Jordan, who now lives out-of-state. Pratt “was all over the news, and [Tommy] stated he was going to shoot ‘that rich nigger,’ or words to that effect. I honestly don’t recall money being the motivation. It was a monumental hate crime, I think.” After all, Pratt’s home address was listed in the phone book. All Kirk had to do was look it up.

Jordan told a similar story to cold-case investigators in recent years. “It wasn’t money,” she said in one statement. “I remember him calling that guy a ‘rich nigger.’ He says ‘I’m gonna kill a rich nigger.’ That’s why he did it.”

Her late husband, getaway driver Mike Jordan, seemed to support that theory in a statement he gave to the FBI in 1995, when the agency briefly reopened its probe following the P-I story. Interviewed at his cell at Walla Walla, where he did time for robbery, Jordan said Kirk killed Pratt for “being a black dude in a white neighborhood.” Jordan did not disclose his own role in the Pratt murder to the agents, but he did confess it to other inmates, who relayed the story to authorities, records show.

The FBI also heard from a source at that time who said Kirk had admitted the killing to him. When the source asked why, Kirk answered: “Well, not really anything, you know. It was just a trip, man.”

Danella Jordan was at her north Seattle home the night of January 26, 1969, when husband Mike, who owned a Buick matching the getaway-car description, walked in with Bart Gray and Tommy Kirk. It was just hours after Pratt’s murder. She had been chatting with a friend, Dave Brinkley, who died from cancer in 2006, not long after he gave investigators a statement about what he’d seen and heard that night.

“Dave was there and [the threesome] came in all wired and freaked out, very excited,” Jordan recalls. She does not say outright that she knew Kirk had murdered anyone. But she’s willing to talk about his likely motive.

“I don’t remember any talk of money,” she says, “and I assume I’d have known.”

Her husband, at least, never flashed any extra cash during their drug-fueled days, she says. “The interesting thing is I am sure Mike didn’t get any money . . . We made money selling Desoxyn, also Desbutal, writing prescriptions for these drugs. Believe it or not, such a thing wasn’t illegal then. So we were never broke . . . The only reason I wasn’t swallowed by drug addiction was my mother prayed for me daily.”

Mike, she adds, “was wildly in love with a Texas whore, running from the Texas Rangers, so she said. If he had big bucks, perhaps it was her he spent it on.”

Brinkley, the other person at the Jordan home that night, said in his 2006 statement to cold-case detective Tompkins that when Kirk, Gray, and Mike Jordan came through the door, “They were pretty pumped up and, like, um, I don’t know if it was ’cause they were loaded, wired, or whatever, and they were carrying a 12-gauge shotgun with ’em.”

Detective [Tompkins]: What happened next?

Dave Brinkley: Ah, tell you the truth, I think they sat down, did some dope, and I looked at the shotgun.

Det.: When you say looked at it, did you physically touch it?

DB: Yeah. I physically touched it . . .

Det.: Okay. Um, so you’re looking at the shotgun. They’re doing drugs. What happens next?

DB: They take the gun and went down, and went down in the cellar . . .

Det.: Were you at all concerned that your fingerprints were now on this gun? . . .

DB: Yeah. As a matter a fact, I was.

Det.: Okay. Did you make any comment to them about that? . . .

DB: No. Actually I didn’t because to tell you the truth, um, Tommy Kirk kind of ah, scared my ass, you know . . . I had enough sense to know that if you screwed with Kirk, he was a psychopath, man.

Det.: Okay. So the gun goes down in the crawl space. Then what happens?

DB: I don’t know. I wasn’t down there. But I would assume they buried it.

Det.: Okay. And then what?

DB: Came back upstairs, and it was like, God, I never, God, I have never seen anybody do this in my life, but Tommy Kirk started shooting dope, and it was like, it was, believe me, it was, I, I have never got this, ’cause he had, he had like a jug of this, and it was just, he just, he’d take, take a syringe, he’d take it in there, he’d fill it up. That’s no shit, man. And it was, it was like gross. I mean, he’d just bam, and he just, till it was gone. I mean, he did enough dope that would of killed like all three of us, you know.

Det.: What kind of dope was it? . . . It wasn’t methadone was it?

DB: No. No. It was, um, ah, percodan, or um, I think it was percodan. But see he had, ah, but somebody had done a drugstore, and he had like a jug, a jug. There was so much dope in that house it was pathetic, you know. It was a jug, and he just, you know, took a jug, filled it full of water [mixing it with the drug] and started banging it.

Brinkley constantly referred to Kirk as psychopathic, and recalled, “I’m sitting over there one night and, you know, they bring this poor schmuck in there that owed him some money, you know, and all of a sudden he whips out a .38 and starts popping rounds off at him, you know, and I’m sitting there thinking Jesus Christ man, he’s gonna kill this, he’s gonna kill this guy, and I’m gonna be involved in this shit . . . He’s got this gun and he’s just going like this, bang, bang, you know what I mean?”

Another source told investigators that Kirk—who grew up in Mountlake Terrace, got an early start on meth, and had an extensive criminal record—threatened to shoot a man in a dispute over ownership of a TV set. Records also show Kirk was arrested for breaking into a Queen Anne home, where he fired three warning shots at another drug dealer, just two weeks before the Pratt murder.

Some of the witnesses who knew Kirk and think he was hired to kill Pratt have speculated he was paid $10,000 to $25,000, which he supposedly split with his accomplices. Most of the take was blown on women, booze, and drugs, say investigators, although Kirk reportedly used some of his money to buy a used Corvette.

But, says Danella Jordan, “The only Corvette I remember Tommy in was a stolen candy-apple-red one. It was from California and had been flipped end over end, didn’t run all that well.”

Kirk lived only four months beyond the day Pratt was killed. He was murdered by co-conspirator Gray. The two were often rival drug dealers, and were fighting over money and a girl when Gray shot Kirk four times while he was behind the wheel of a car at a Capitol Hill intersection in May 1969.

The suspicion was that it had something to do with the Pratt murder. Not so, says Jordan. “Mike said Bart shot Tommy because of Bart’s squirrelly girlfriend Toni,” she claims. “I don’t remember her last name, but she was a runaway daughter of a big-name lawyer in Seattle, drawn to Bart’s dark personality and bad rep. Of course she was attracted to Tommy, all strutting around. One thing led to another, and Bart shot Tommy driving a borrowed car—which ruined the [car] owner’s life, as he’d just got a job and got back with his old lady. [You] shouldn’t lend your car to hoods.”

Gray was later convicted of manslaughter for Kirk’s slaying. Gray, according to records, privately confessed his role in the Pratt murder to friends before he died of a heart attack in 1991. Mike Jordan died in 2006 at age 58 without ever disclosing to police his role in the murder.

For her part, Danella Jordan reiterates her feeling that Kirk thought up the killing on his own and got his buddies to go along. But she didn’t want to talk about it anymore, she said, after several days of e-mail exchanges. “I’ve spent a week in the museum of my mind and can’t come up with any more info,” she said. “Just bad memories.”

Jordan’s comments strike a chord with Larry Gossett. “Of all the theories we have discussed,” says the councilmember, “that one sounds just intuitively a more likely truth about what may have happened. The others sound less likely to have been the truth.”

Today, Pratt, whose body was interred at St. Mark’s, is memorialized by a park and a fine-arts center on Yesler Way in Seattle. Both sites bear his name. Gossett, among others, hopes the community doesn’t forget Pratt, and wishes his murder case could ultimately be closed.

“It’s been five decades,” says Gossett, “and in my view, there’s enough here now to solve this thing.”