In 2002, Steve Moriarty, former drummer for legendary Seattle punk band the Gits, noticed that a certain eBay buyer from Los Angeles had started buying up almost anything he put up for bid—from vinyl copies of old Gits recordings to sweatshirts, T-shirts, and posters, sometimes paying outrageously generous prices. “They were winning things and sending me notes through eBay saying ‘I really like your band, and boy, if you have anything else, we’ll bid on anything you put up,'” recalls Moriarty. “And I was like, ‘OK, who are these weird people?’ I was kind of creeped out.”

When the buyers drove the auction price for a live Gits album recorded at Portland’s now-defunct La Luna club up to $110, Moriarty decided it was time to contact them via e-mail. He had an entire box of that particular record, and didn’t feel right about accepting such an exorbitant sum. “I said ‘Look, I’ll give it to you for $10’.” But the buyers insisted on paying the full eBay bidding price, so Moriarty tossed in some T-shirts and additional records to compensate them and assuage his conscience. Following this exchange, a tentative friendship sprung up between Moriarty and the buyers—who turned out to be two women in the film industry: aspiring producer Jessica Bender and budding director Kerri O’Kane, who shared an obsession with the Seattle band and their late singer, Mia Zapata.

O’Kane was the one who turned Bender on to the Gits and Mia Zapata. While battling ovarian cancer, O’Kane was reading a book entitled Manifesta: Young Women, Feminism and the Future and saw a footnote in the resource section about an organization called Home Alive. Home Alive was founded in Seattle in 1993 after the violent murder of Zapata, who was 27 at the time of her death. O’Kane began researching Zapata and the Gits online, and eventually bought a copy of the Gits’ posthumous album Seafish Louisville, a purchase which unwittingly set her up not only for a compulsive eBay addiction, but for an absolute immersion in a band that won her head and heart in a way she never expected.

“I didn’t know how inspired I would be,” says O’Kane, still sounding incredulous at how deeply the opening track “Whirlwind” marked her. “I’m from L.A., I grew up with [female-fronted punk] bands like X, but I was so incredibly moved by Mia’s voice. She’s so unique in her vocal presence. She has a little bit of punk, a little bit of blues, but there’s a candor in her lyrics that’s just not in a lot of the music you hear today.

“I became obsessed with [Zapata’s story] and my whole intention was to see the film that was made about her,” continues O’Kane, sitting in the dining room of her Hollywood home—a humble but meticulously decorated 1930’s duplex, once belonging to her grandmother and now filled with vintage furnishings and Gits memorabilia. “I figured there must have been something, but there wasn’t anything except for Hype!” Doug Pray’s 1996 movie about the Seattle music scene features brief live footage of the band.

After they received the generous care package from Moriarty, the women decided it was time to act on the dream that had slowly been taking shape in their heads. Via e-mail, Bender gingerly suggested to Moriarty the possibility of a movie about the Gits. He and the other surviving band members, bassist Matt Dresdner and guitarist Andrew Kessler (aka “Joe Spleen”), were initially uninterested. “I was kind of neutral to the idea,” says Moriarty. “But Matt and Andy—which is their nature—said ‘No, what are you talking about? We don’t want to make a movie. We want to leave it alone.’ So that’s how we left it.”

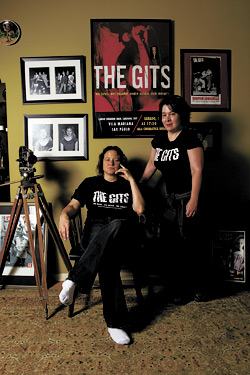

Now, on the 15th anniversary of Zapata’s murder, the final cut of Bender and O’Kane’s documentary, simply entitled The Gits Movie, is about to screen in Seattle and a half-dozen other cities, including Louisville, where Zapata is buried. With Moriarty’s help (he eventually became a producer), the two women were able to get interviews with those among Zapata’s friends and family who had been previously reluctant to speak, and access to obscure tracks and memorabilia. They also made a film that respected the wishes of those most closely associated with the band—capturing the life of the music, rather than the tragic death of the singer.

On July 7, 1993, Mia Zapata said goodbye to her girlfriends in the band 7 Year Bitch after a seemingly normal night of beers and bonding. She left Capitol Hill’s Comet Tavern to head home, but within two hours had lost her life to a predatory transient named Jesus Mezquia. He beat her, strangled her with the cord from her hooded sweatshirt (which bore the name of her band), and, after sexually assaulting her, left her body on a dead-end street in the Central District, a little less than two miles from the Comet. The case went unsolved for a decade, until a DNA match was found tying Mezquia to the crime. He was sentenced to 36 years in prison.

In the wake of Mia’s murder, a coalition of her peers started Home Alive, a nonprofit dedicated to teaching practical self-defense skills at affordable rates. Fifteen years after Mia’s death, Home Alive continues to thrive and has a history of drawing significant fiscal support from musicians moved by the cause, from high-profile established acts like Joan Jett and Pearl Jam to ambitious, feminist-minded local punk bands like Ms. Led.

“The year Mia died, I was just a baby riot grrl at that point, living in suburban Michigan and trying to figure out my place in the world,” says Ms. Led front woman Lesli Wood. “I had just started getting into 7 Year Bitch and Tribe 8, and it was around that time that I heard about this woman who had been so brutally murdered. Honestly, in my 18-year-old mind, she was the kind of person I was trying to grow up to be, and it was frightening that someone that seemed so tough and aware could be a victim of what was essentially my worst fear.”

Back in Seattle, having that fear become a reality had a chilling effect on what had been a very free-spirited and confident artistic community, many of whom—including all four members of the Gits—had moved to the city in the late ’80s from Ohio’s progressive Antioch College. “I think that even prior to her death, the reason Mia appealed to a lot of women was they could see themselves in her when she was up onstage,” explains fellow Antioch alum Ben London, a close friend of Zapata’s and a veteran Seattle musician who now heads the Northwest chapter of the Recording Academy. “There weren’t a lot of other outlets for that locally at the time. The same way they could see themselves in her on the stage, they could see themselves being a victim of the same kind of crime. And that’s why it resonated so much with the community.”

“There was a very clear change in attitude in the Seattle music scene,” remembers former Faster Tiger guitarist and all-around veteran Seattle musician Mike Katell, a long-time friend of Dresdner. “After her death, the community became more serious. The creation of Home Alive galvanized a lot of people around violence against women, and the loss of the Gits and the energy they were contributing also had an effect—it turned us inward. The Gits and the other people in their circle were so spirited and fun. After Mia died, that went missing in our small world. We felt mortal. You could hear it in the music.”

Nowhere could this be heard more evidently than on ¡Viva Zapata!, the extremely successful 1994 album by 7 Year Bitch, dedicated both to Zapata and to their former guitarist, Stefanie Sargent, who had died in 1992 of a heroin overdose. The album’s thematic centerpiece was “M.I.A.,” a tense and epic hard-rock anthem with lyrics (“Does society have justice for you?/If not, I do”) that could either be interpreted as a cry for vigilante justice against Zapata’s killer or a simple revenge fantasy.

“I hate to admit it, but a lot of good music probably came out of that—the anger, the grief,” continues Katell. “But then too, a lot of great music was lost.”

Speaking from his Louisville home on Father’s Day, Richard Zapata says his daughter “was trying to the best of her ability—along with the band—to become a success. It was totally destroyed, like slamming a door, it was gone forever. More intimately, the boys who were in the band—their dream was literally just ripped right out of their hearts and they’ve never been the same.”

Reopening that door and talking to the band in order to make a documentary wasn’t going to be an easy task for O’Kane and Bender, and it took a great deal of time and delicate communication of vision to make that happen. Though Bender had been gaining experience working in television and film in L.A., and O’Kane had directed a handful of shorts and music videos, neither had extensive experience in getting a film off the ground on their own. After considering a variety of angles, they decided the best approach would be to follow basic punk-rock principles and aim to keep the focus more on the music and less on the morose.

“I just didn’t want the Gits to go down like that—known only for the ‘brutal murder of their fiery lead singer,'” says O’Kane, gesturing dismissively to emphasize the faux-sensationalism of her phrasing. “All the information on the Internet about Mia seemed to be about how she died. [There wasn’t as much] about the composition of the band or why they loved making music together.”

Despite the initial rejection they received, the women persisted via e-mail, offering to come to Seattle and meet with the band members in person. Moriarty eventually agreed to arrange a meeting, and the women flew up to make their pitch. “That meeting was very hard and we were very nervous,” remembers O’Kane. Though Moriarty appeared to be warming to the idea, while they met over coffee at Capitol Hill’s Caffé Vita in early 2002, Dresdner and, in particular, Kessler remained unconvinced. “[Kessler] was not into doing the movie with us, and I was still wanting to forge on,” O’Kane continues. “He was like ‘Good luck, I’m not going to be in it,'” remembers Bender. “But then I asked him if we could just do a brief audio recording, which we did, and we just kept hanging out with them.”

“I just started to understand Andy more,” explains O’Kane. “He said to me, ‘Imagine how you would feel if all you hear on the news and in the newspapers about your band is not [regarding] the music, but about the brutal rape and murder of your best friend?’ And that really struck a chord with me. I tried to instill in him that [even though I was an] outsider, I was really moved and touched by the music they created and just wanted the Gits to be out there.”

“They seemed like they were in it for good reasons and wanted to tell the story of the band and the music…they promised that they weren’t going to dwell on Mia’s murder,” says Dresdner.

Going through his personal collection of memorabilia helped solidify Moriarty’s interest. “I had tried to archive all our recordings, all of our photographs, and all of our interviews. When they needed it, I had all the stuff to make a film already. I was available to give them obscure music tracks and other stuff I had squirreled away. Once they turned a corner and decided to put the emphasis on the music, then all three of us got on board. There were two things: First, you have to make lots of music in it—more music than talking—and you have to make it funny. If you can do that, then we’ll be involved.”

Hype! director Doug Pray also ended up stepping in and helping out immensely with momentum. “He donated shitloads of film and music and was very cool about helping [Bender and O’Kane] out,” says Moriarty.

After that, Moriarty began the uneasy process of introducing the filmmakers to the Gits’ circle and convincing people they were trustworthy.

“For a long time I wouldn’t talk about it with the press out of respect for those guys,” remembers Ben London, who was working as a curator at the Experience Music Project when filming started. “I was really tired of hearing a lot of people talking about what Mia was thinking, what she wanted, or what she was doing. I just always felt like the only people at that point that could effectively speak to her and what she was thinking were the people in that band and her family. I think the fact that Steve wanted to start working with them…and then the fact that Matt and Andy signed on said to me that it was OK.”

At that point, 7 Year Bitch drummer and Home Alive co-founder Valerie Agnew got involved, as did other members of 7 Year Bitch and Zapata’s one-time roommate and close friend Julian Gibson. Mia’s father and brother were ready to talk as well, but one key figure was never comfortable with speaking on camera: Mia’s mother. “She didn’t want to be interviewed. We did try, but it’s too much for her. Too painful,” says Bender.

Bender was working 60-plus hours a week as a sound engineer on the HBO series Six Feet Under at the time filming commenced. It was her salary that ended up funding the majority of the film’s roughly $250,000 budget, though she still remains deeply in debt. Cooperative film studio Wiggly World helped out as well, and a last-minute influx of cash from Gold Village Entertainment owner (and former Nirvana manager) Danny Goldberg allowed the women to add interview footage of Kathleen Hanna and Joan Jett. Jett’s commentary adds much to the film’s quiet poignancy, particularly when her tough-girl façade cracks on camera while discussing meeting the surviving Gits for the first time. When Zapata’s peers grew frustrated with the lack of progress on the murder investigation, Jett worked extensively with the band on fundraising efforts to hire a private investigator.

Goldberg’s presence eventually evolved into that of executive producer, which helped the film secure stronger distribution offers and a more prominent place on the industry’s radar. O’Kane and Bender eventually signed a deal with Liberation Entertainment, a distributor with a significant reach into U.S. and European markets. In the coming months, The Gits Movie will screen at more than 35 theaters and film festivals, and will be released on DVD July 8.

The film Bender and O’Kane ended up with succeeds in large part because of its straightforward approach. As promised, much of the focus is on the music, with live footage that extends all the way back to basement parties at Antioch and forward to packed club shows in Seattle, vividly illustrating the sheer power of the band’s shows and Zapata’s effortless charisma, charm, and goofiness. The joy and humor that mattered so much to Zapata’s bandmates is definitely up front, particularly when the band discusses the debauchery of their first European tour or Zapata’s endearing, but uneven, ability to tell jokes on stage. For obvious reasons, things take a dark turn in the second act when the murder occurs, and a dramatic turn in the final act, when the trial and aftermath are depicted. However, O’Kane wisely does what the best documentary filmmakers know how to do: get out of the way of the subject matter and let the story tell itself.

Discussion of the long-term effects of Mia Zapata’s death inevitably turns towards Home Alive, and there have been grumblings over the years that the organization is exploiting Zapata’s memory for its own purposes, however noble they may be. Home Alive’s current executive director, Becka Tilson, who took over in 2005, is obviously cautious about making Mia a martyr for their cause. “We open every [self-defense] class with the story of how Home Alive started. But it’s important not to say things like, ‘Home Alive started because of Mia,’ or that all of a sudden this person died and everyone figured out that violence was an issue,” asserts Tilson.

“People would say that about Home Alive—’At least something good came out of the whole thing,'” says Moriarty, with a trace of resentment. “And I’d be like, ‘What? Home Alive, yeah, that’s good, but is that something good that came out of this? No, it’s something that should have been here before this…then it might not have happened.’ People try to look on the bright side and sometimes there isn’t a bright side.” That said, it’s clear that Moriarty respects Home Alive’s work and harbors no ill will. “I definitely thought that was a cool story that was part of the whole thing.”

What’s more, the fact remains that Mia’s death and the formation of Home Alive signaled a new era of political activism within the music community that hadn’t existed with such effective potency before. “Mia being murdered was like the music community being attacked,” says Fuzed Music owner David Meinert, a notoriously vocal political activist in music-community issues who also manages the careers of local hip-hop stars the Blue Scholars and Common Market. Meinert and others see a correlation between the momentum from Home Alive and the 1995 formation of JAMPAC (Joint Artists and Musicians Political Action Committee), the organization that eventually helped overturn the constrictive Teen Dance Ordinance in 2002. “With Home Alive, you had people organizing something that had a specific action to it…there was nothing so coordinated around one issue that continued for so long. I think that showed people the potential of what a community can do when it stands together and supports a cause.”

Unsurprisingly, Richard Zapata sees both sides of his daughter’s impact on the community of her adopted home in Seattle. “The collateral damage seems to stick out for me,” he says softly. “There were so many people at the time that were shocked and frightened by what had happened in that part of the city. When I’ve seen the film, I’ve been left with that—the ripple effect of what happened.”

He feels a special concern and affection for Moriarty and Kessler. “You look at them and you can’t help but think about what might have been. I remember for 10 years, when I ran into Steve or Andy, I cried. I could be walking down Broadway and goddamn it, I’d see Andy walking toward me in the crowd, and by the time he’d get to me we’d be embracing and crying. During those 10 years, I probably saw him 15 or 20 times, and every time I saw him it was the same thing. I couldn’t just walk up to him and say ‘Hey, Andy, how are you?’ I would venture to say if I saw him today I’d have the same reaction.”

Perhaps what is most striking about talking with the man who had to bury his daughter far too soon is the comfort he finds in reflecting on how much Seattle has treasured her memory. “Mia was not born in the state of Washington. She was not raised or educated in the state of Washington, but after the crime, the city of Seattle literally took her into its bosom. And year after year, while we waited for someone to be apprehended, the people of Seattle never forgot. That has always been extremely comforting to me. I think that is a real tribute to the citizens that make up Seattle. It’s a very caring and loving city. Sure, it has its problems and it’s made its mistakes, but by and large, it has a very wonderful heart as far as I’m concerned.”

The Gits Movie will screen for a week at the Northwest Film Forum starting Fri., July 4. Bender will also attend a one-night showing at Metro Cinemas at 8 p.m. on July 7, followed by an afterparty at the Comet.