Kurt Niklas is the first to admit that he’s “on the verge” of being a hoarder. His Cate Apartments unit in Greenwood is filled with odds and ends that paint the portrait of an unconventional life, one marked by an undulating cadence of joy, grief, and deferred dreams. Jewelry from Value Village and the Goodwill dangles from hooks on the walls, cabinet knobs, and clothing hangers. A table in this one-bedroom flat is piled with sundries that include a horse mask, a boomerang, a green wig, and a plush toy reindeer donning an eye patch. The desk lamp that rests in a red bucket casts a psychedelic, multi-colored glow to the pile. Six skateboards are scattered throughout the place like the subjects of a hidden object game.

No boxes can be seen among his pile of belongings, notable considering Niklas was served an eviction notice a week beforehand.

The 52-year-old is beset by a host of mental health diagnoses: post traumatic stress disorder, attention deficit disorder, bipolar disorder, and depression. His habit of accumulating stuff has accompanied a growing acceptance of loss. “That’s why I kind of gather things, because I don’t have anything,” he says while sitting on a fold-up chair in his apartment last Tuesday. “Whatever I can hold onto, I try to.”

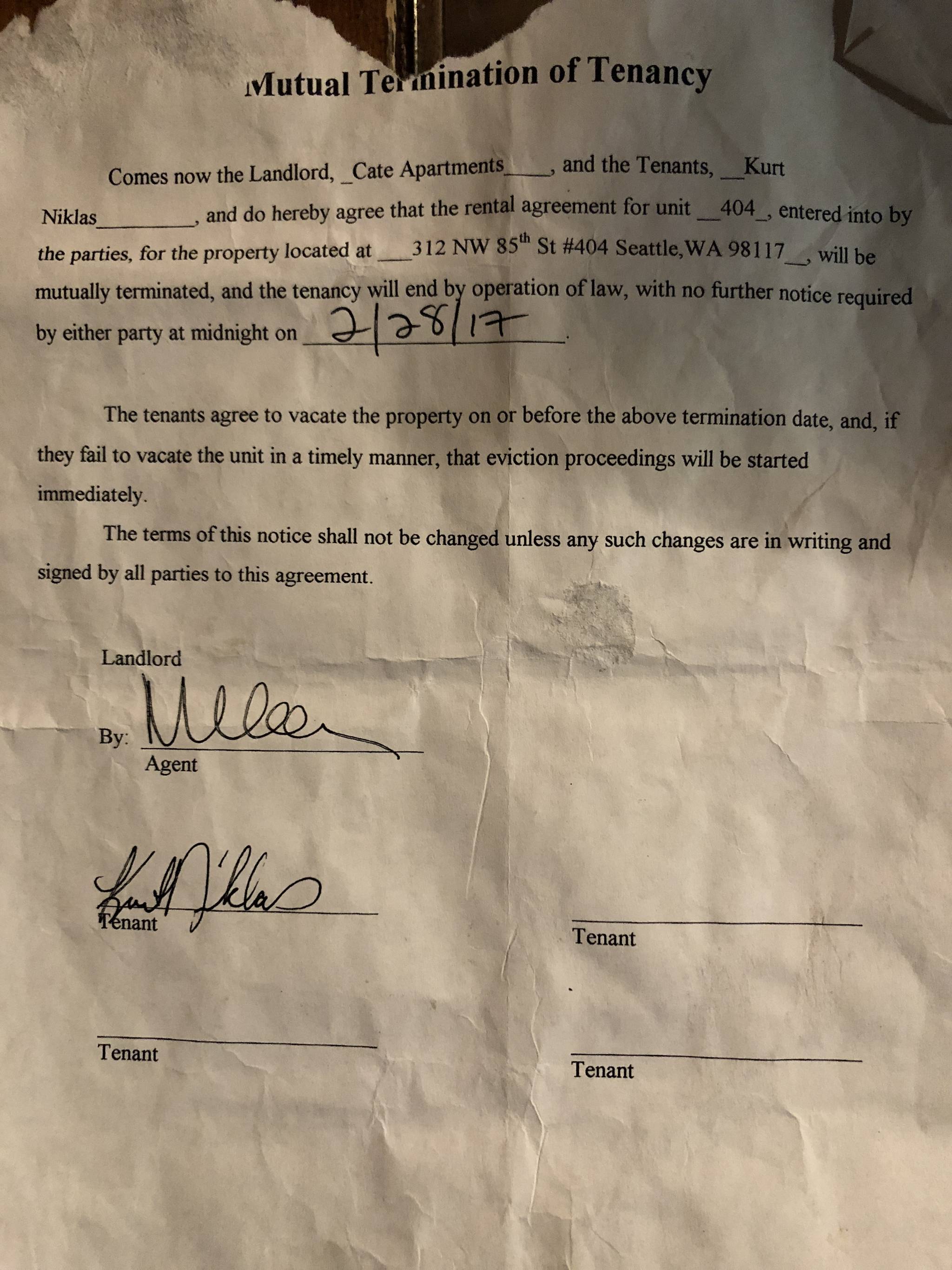

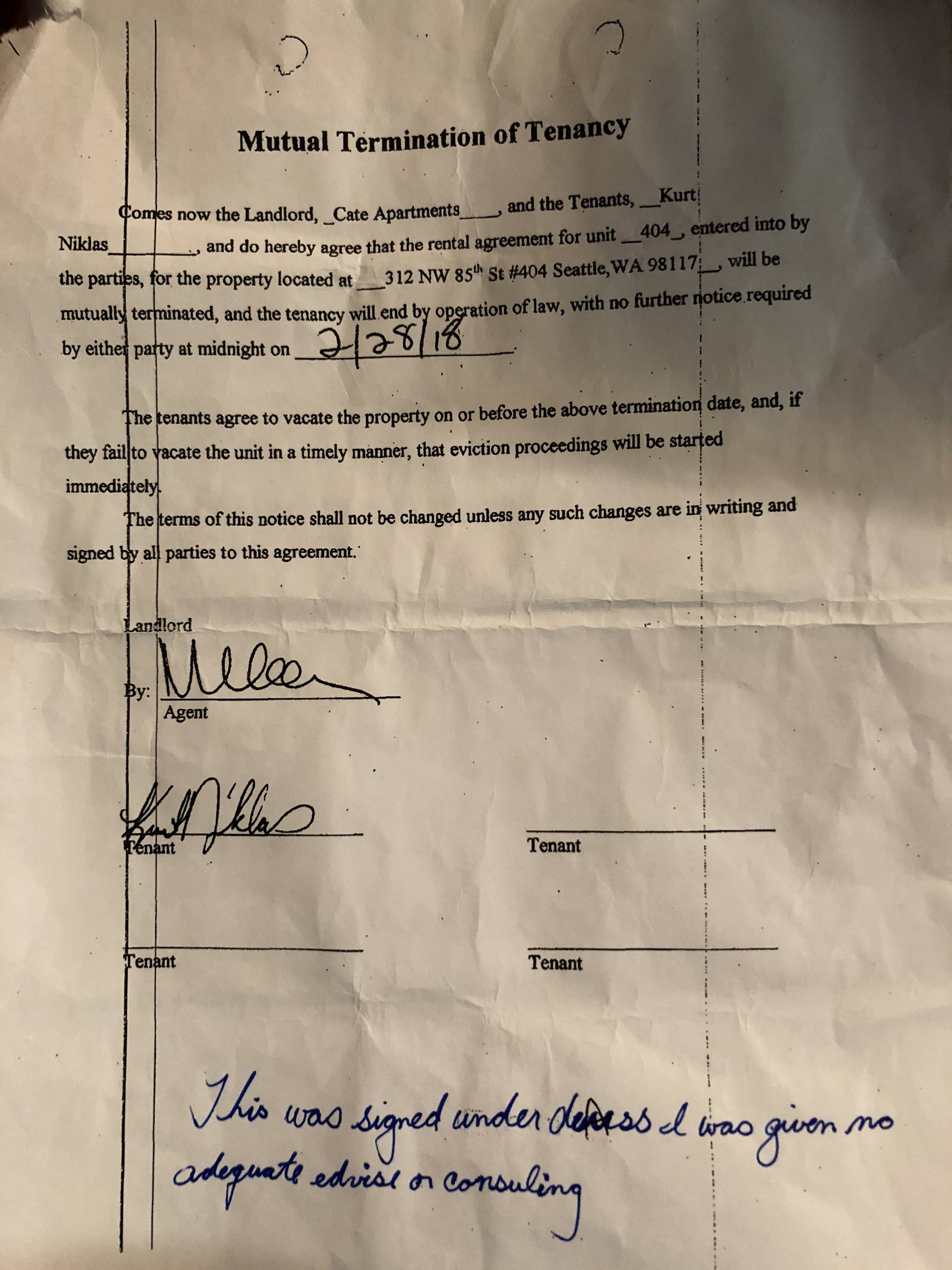

Niklas’s impending eviction comes as the result of failing to vacate his unit after signing a mutual termination of tenancy agreement, a contract between a tenant and landlord that terminates the lease early on an agreed upon date. Niklas’s agreed-upon date was February 28, but he hasn’t left because he says he didn’t understand the contract’s ramifications. His case is an example of how these agreements are misused to remove vulnerable low-income residents from their properties without just cause, say tenant rights advocates.

Sitting in the overstuffed apartment, the Los Angeles-area native relays a series of misfortunes that began about 12 years ago, when, he alleges, acquaintances jumped and nearly beat him to death, causing him to spend several months in the hospital recovering. He says that his acquaintances stole equipment for his carpeting business, which caused him to lose his successful company. Niklas adds that boats he owned were impounded while he was in the hospital.

About five years ago Niklas came north to work for his brother’s property management company and “to get away from L.A.” Niklas lived in his brother’s SUV and trailer at Green Lake for a time until he secured an apartment through the state-run housing assistance program Housing and Essential Needs. The program covered most of the $900 rent on his Lynnwood apartment, until funds ran dry seven months later. Two years ago, he lost everything in that apartment when he could no longer pay the rent and was evicted, catapulting him into a year of homelessness.

But the Navy veteran’s luck seemed to turn around when Veteran Affairs Puget Sound offered him a free spot in transitional housing for two years. In January 2017 he moved into his current apartment, which is operated by the affordable housing provider Low Income Housing Institute (LIHI).

At first, Niklas reveled in the newfound freedom and loved his neighbors at Cate Apartments. But then he began to butt heads with the property manager and says he lost his job at his brother’s company due to a continuous conflict with him. His mental health issues have kept him from finding other work since. He’s currently relying on cash assistance as he waits to receive disability payments, and a voucher to secure more permanent housing.

During a routine inspection of his apartment last November, Niklas’s property manager suggested that he sign a mutual termination of tenancy agreement. Niklas claims the property manager told him, “This is just to speed up the process when you get your permanent housing.” Niklas believed that it would help him immediately move into his next apartment by liberating him from his lease once he received his housing voucher — and not beforehand — so he obliged and signed the document, although he now says that he didn’t fully understand its meaning. He was particularly confused because the agreement he signed listed a February 2017 move-out date, although the property manager later showed him one that he believes was forged, with the “17” changed to an “18.”

Now Niklas braces for yet another possible loss as he faces an eviction hearing on Tuesday, April 10 for neglecting to move out of his apartment in February. He says that he has nowhere else to go since he’s still waiting for his housing voucher, and that losing the apartment “would kill me.”

Several local attorneys and tenants rights organizations say that Niklas is just one of many low-income tenants throughout King County who have been encouraged to sign mutual termination of tenancy agreements that ultimately strip them of their rights to stay in their apartments, agreements that they didn’t understand because they lacked counsel. One Tenants Union of Washington State organizer says that the agreements capitalize on the imbalanced power dynamic between landlords and unrepresented elderly or mentally disabled tenants. Advocates argue that mutual termination of tenancy agreements allow landlords to circumvent local just cause eviction policies—such as The Washington State Residential Landlord-Tenant Act, which prevents landlords from evicting tenants without court orders, and a 1980 Seattle ordinance that safeguards month-to-month tenants from unjust cause evictions. Because they fly under the radar of the court system, they say these agreements permit landlords to end the leases of tenants they dislike, without the burden of proving just cause for doing so. The extent of this issue is largely unknown; the Seattle Office of Housing strategic advisor Robin Koskey told Seattle Weekly she doesn’t believe that any city departments track how many such agreements are negotiated per year.

If a tenant who signs one of these agreements neglects to vacate the unit by the date listed on the contract, that tenant can be evicted. Any history of evictions can affect a tenants’s eligibility for receiving rental assistance such as the Housing Choice Vouchers Program (formerly Section 8) and hurt their chance of being accepted into certain buildings.

Edmund Witter, managing attorney at the Housing Justice Project, says that about once a week a low-income resident in an affordable housing unit will come into his office because they signed a mutual termination of tenancy agreement without counsel and were then put through eviction proceedings when they didn’t move out. Many of the tenants are elderly, low-income or people with disabilities, and risk becoming homeless if they haven’t secured a place before the move-out-date on their mutual termination of tenancy agreement. Moreover, Witter adds that it’s “pretty much impossible” for a tenant to contest an eviction during a show cause hearing if they’ve signed the mutual termination agreement.

But low-income housing providers contend that the agreements are rare, and are designed to help tenants avoid an eviction on their tenant record if they’ve repeatedly violated the terms of their lease.

Sean Martin, executive director at Rental Housing Association of Washington—a resource for rental managers and owners—finds it surprising that tenants wouldn’t understand the terms of mutual termination agreements. He says that they are usually used when tenants express a desire to end their leases early because they need to relocate for work, or can’t afford their rent anymore. Sometimes a landlord will ask a tenant to sign the agreement if there’s a family emergency and the unit is needed for a relative, although he says that is very uncommon. “It’s very surprising to hear stories where people are not understanding what they are agreeing to, so I don’t know if that merits an attorney or someone else reviewing the document too,” Martin says. “Unless there was some kind of mental issue going on where someone [thought] … ‘I’m just going to sign this and get it out of my way, and not have a stress in my life,’ it just seems like something that’s pretty straight forward.”

Regardless of landlords’ motives for issuing them, the agreements undoubtedly contribute to the county’s growing homelessness crisis. The local homeless population increased to over 11,600 people in January 2017, according to the most recent All Home’s annual point-in-time count report.

For many vulnerable people, access to housing is a life or death matter. Chris C., a LIHI McDermott Place tenant (who asked that his full name not be used out of fear of retaliation from the agency), says that one of his neighbors in the building became homeless after signing a mutual termination agreement last year, and soon after died. Chris says that his neighbor Christen Beaty was addicted to alcohol and sometimes “his behavior would be a little outlandish, but nothing real bad.” For instance, one day Beaty hit a golf ball down the hallway while he was drunk. But “he was always overly nice, even when he was drunk,” Chris noted. Beaty later told him that the property manager encouraged him to sign the mutual termination agreement, because “if he just didn’t sign it and go ahead and move out, they were going to kick him out anyway.” Chris says that Beaty became homeless after he vacated the unit, and his dead body was found near the apartment building a few weeks later.

In Niklas’s case, he believes that he’s being pushed out of his place as an act of retaliation. Niklas suffers from insomnia and often patrols the nearby alleyway with one of his neighbor friends when he can’t sleep, but he says the late-night activity raised the suspicion of the property manager. The complaints were compounded by ongoing accusations that he wasn’t picking up after his German Shepherd service dog Leo.

Niklas had forgotten about the mutual termination agreement and says that his property manager didn’t mention it again until one evening a few weeks ago. He says he was pressure washing the alleyway and the garage at 11 p.m. to remove dirt and debris following heavy rain; but the job took him longer than he expected and he was still cleaning when tenants left for work the next morning. What he intended to be a gesture of goodwill backfired when the garage flooded and excess water seeped into the elevator. A few hours later he says the property and area managers banged on his door and told him, “Get your shit out of here right now! You’re not even supposed to be here.”

He received the eviction notice about a week later in late March, and then asked attorneys at the Housing Justice Project to take on his case. (When asked to verify some of Niklas’s claims, LIHI Chief Financial Officer Lynne Behar told Seattle Weekly that the organization’s contract with the VA prevented her from confirming or denying whether Niklas is a tenant at Cate Apartments. VA Puget Sound Health Care System’s Public Affairs Specialist Kimberly Wilkie told Seattle Weekly that her agency is also unable to share details about Niklas’s case under the HIPAA Privacy Rule.)

“I’m in shock, man, because I don’t want to go through [homelessness] again,” Niklas lamented, adding that the stress of the upcoming hearing has exacerbated his insomnia and affected his appetite. He urges LIHI to “just be able to have some sympathy and compassion, because that’s what we’re coming in here for.”

Niklas’s friend Chad Stewart, who has lived in the building for nearly a decade, agrees. “People are coming here off the streets, they’re coming off drug addiction, alcohol,” says the 46-year-old veteran who had also experienced homelessness before landing into his LIHI apartment. Stewart says that he has seen a pattern of intimidation and retaliation under the building’s new managers, who he believes hold too high of expectations for tenants. “You don’t come here because your life is in order. You come here because you’re starting over and they’re supposed to help you do that.”

However, Behar insists that the agency is fulfilling its mission by operating about 2,000 apartment units for previously homeless and low-income people. Each building has its own set of requirements established by the funders (such as the Department of Housing and Urban Development or King County) at the time that they’re developed, and most of their buildings have case management services.

Behar says that her agency doesn’t have a blanket policy on issuing mutual termination agreements, although she says that they are generally used in lieu of serving eviction notices. “LIHI views asking a tenant to leave as a last resort,” Behar says. “Before that has happened, we have tried to work with the tenant to provide case management services.” The agreement allows the tenant to negotiate when it would be best for them to move out, as opposed to an arbitrary eviction date imposed by the courts. LIHI property managers would use their own discretion to offer tenants the agreements, depending on the population that they’re serving. “The buildings are set up to literally bend over backwards for the tenants,” she says exasperatedly.

In 2017, LIHI had 42 evictions and 14 mutual terminations out of 2,246 households. Still, Washington Community Action Network’s Political Director Xochitl Maykovich is concerned that those 14 tenants didn’t understand what they were signing. “I get there’s situations where … a tenant might need to leave. It’s good that they don’t have an eviction on their record,” Maykovich says. “But what is not good is that people, especially people who are vulnerable, [are] being manipulated into signing a document that loses their housing and then they have no recourse.” She also finds it problematic that low-income housing providers that receive public funding aren’t required to inform government entities of the amount of mutual termination agreements that are signed.

The lack of accountability also irks Tenants Union of Washington State community organizer Helena Benedict. She says that their organization has received six calls from people with situations similar to Niklas’s in the past couple of years, and that all of them were LIHI tenants. She added that some people who call to inquire about mutual termination agreements want to get out of their lease and need advice. “But also it is very common, unfortunately, to see it used … almost more as a threat or coercion tactic.” Benedict adds that she usually hears about the agreements in a predatory context, in which the landlord is taking advantage of a low-income or elderly person who might be a hoarder or have other unsavory habits that don’t quite qualify as eviction-worthy.

During interviews with two attorneys who provide free legal assistance to low-income tenants and two staff members at tenants’ rights organizations, it became clear that LIHI, Seattle Housing Assistance Group (SHAG), and Seattle Housing Authority (SHA)—three housing providers that offer housing to senior citizens, low-income and formerly homeless residents—have reputations for negotiating questionable mutual termination agreements.

SHAG insisted in an email to Seattle Weekly that it encourages tenants to consult counsel before signing the agreement. In 2017, five mutual termination agreements were signed out of 5,200 residents. “The fact that a very small number of SHAG’s residents—less than 0.1 percent—had mutual terminations in 2017 reflects how rare they are and how hard we work to provide each resident a high-quality, stable affordable housing situation at a time when Seattle’s soaring home prices and apartment rental costs are placing extraordinary burdens on so many people in our region,” SHAG’s Chief Operating Officer Karen Lucas wrote Seattle Weekly in an email. “Amid this affordable housing crisis, SHAG offers mutual terminations as a positive outcome to try to help residents successfully find alternative housing when a SHAG community is not the best option for them due to physical or mental health changes or non-compliance with their lease.”

SHA Director of Communications Kerry Coughlin also rejected the notion that tenants were coerced into signing mutual termination agreements under duress. Although SHA doesn’t have a formal policy regarding the agreements, Coughlin says that property managers are prohibited from negotiating an agreement with a legally represented tenant directly. Instead they work with the tenant’s legal counsel, or with a case worker if one is available, to negotiate a mutual termination. Out of over 8,000 rental units last year, the housing provider had seven mutual termination agreements for non-payment of rent and five for lease violations other than non-payment. “These agreements are rare, strictly voluntary and are generally done for the benefit of the tenant. SHA has a commitment to and practice of eviction avoidance. We do all that we can to work with tenants and give and get them the help they need to remain in their housing,” Coughlin wrote in an email to Seattle Weekly.

While the numbers of mutual termination agreements at SHA, LIHI and SHAG are a fraction of the overall tenants, Witter at the Housing Justice Project says that he hasn’t heard of any private landlords entering such contracts.

He referenced one tenant who recently sought counsel at the Housing Justice Project because her landlord pressured her into signing a mutual termination agreement after meth residue was found in her wall during an inspection. The resident didn’t realize that she could refuse to sign the document, and felt that she was being taken advantage of, because she says she doesn’t do drugs. “The problem is that we’ll just really never be able to litigate that one way or the other. We’ll never have the opportunity to go in front of a judge and prove or disprove whether she actually did meth at all,” Witter says. “Because she signed a mutual termination, that’s it … it’s just like signing an arbitration agreement, or a gag order.”

Witter suggested that mutual termination agreements policies needed to be developed to ensure that all tenants are provided with legal counsel before signing contracts that forfeit their housing rights.

But the passage of any state or citywide policies will be too late for Niklas, who hopes that he will secure his housing vouchers soon, in case he needs to leave his place.

Back at Cate Apartments, Niklas stands in the garage that he had flooded just a couple of months beforehand during his night of pressure washing. As Leo rests at his feet, Niklas speaks about his love for nearby Green Lake, which was one of the first places that he’d visited in Seattle while he was homeless and living in his car.

In those days, Niklas would wake up and let Leo out to swim in the freshwater lake, regardless of the weather. Leo would pull Niklas around the lake’s perimeter as he cruised on his skateboard, chatting up passersby. Now he goes to Green Lake to escape the feeling of “walking on egg shells” in his apartment building. But it’s not quite the same. Leo and Niklas are getting older, so their skateboard routine has come to mark the passage of time as much as it has a vestige of an arguably more carefree life. “It’s a reality check,” Niklas says. Leo hobbles behind Niklas as he pulls open the garage door, and the late afternoon light casts a shadow on his face as he waves goodbye.

Update (Wed. April, 11): Niklas received relatively good news about his situation on Tuesday, April 10, the date of his eviction hearing. Housing Justice Project was able to broker a settlement agreement for Niklas, allowing him to stay in his apartment through May 31, at which time he’ll need to move out or face eviction. He will also receive assistance in finding a new residence.