For people who want to start a legal marijuana business, if it’s not now or never, it’s something close to it.

On Monday, Nov. 18, the state Liquor Control Board will open a 30-day window for applicants seeking a license to produce, process, or sell marijuana. Some time later—the board hasn’t announced exactly when—it will begin to accredit marijuana testing laboratories.

The beginning has finally come for the nuts-and-bolts implementation of Initiative 502, passed by voters last November and making Washington one of only two states, with Colorado, to legalize recreational marijuana. It’s a historic occasion that many have likened to the end of Prohibition.

But the dawn of what Fortune has called “Marijuana Inc.” has some unique twists and turns. For one thing, Washington’s would-be entrepreneurs get this one shot at a license—perhaps their only shot ever. While there is a chance the LCB might open another window at some point, spokesperson Brian Smith allows, “There are no guarantees.”

“This is not like any other business market,” he explains. He elaborates that LCB members deemed the 30-day period a way to limit the number of pot businesses in the state, which they thought necessary to protect public safety and avoid the wrath of the feds. “We’re walking a fine line here,” he says.

Hence the current frenzy of entrepreneurial activity. Aspiring business owners have pored over the 40 pages of regulations approved by the LCB last month, looking for angles and sometimes cursing restrictions. The cap on retail licenses—334 across the state, 21 in Seattle—looms large. So does the three-license limit for any one individual or business, which the LCB has said is meant to prevent big-money companies from swooping in and dominating the market.

In the days leading to the application window, the prospective business owners are preoccupied with financing, branding, and, especially, real estate. Applicants must submit an address where their business will be located. Already a difficult task for any business, it is made harder by a myriad of marijuana-specific obstacles.

To avoid a backlash from the federal government, which still considers marijuana an illicit substance, the state has adopted restrictions important to the feds. Applicants cannot declare an intention to set up shop within 1,000 feet of schools, parks, libraries, or other facilities frequented by children. And then there are local zoning codes and the wariness of landlords to consider.

Still, some prospective sellers have grand plans. Others are aiming for a niche market. A good number have moved here from across the country—or in one case, the world—to get in on the industry’s ground floor. Many are homegrown. They are in their 20s, 30s, 40s, and 50s. One is a Ph.D., another a grandmother, yet another a self-proclaimed “multimillionaire.”

Here are the stories of four businesses trying to overcome those obstacles, legitimize marijuana, and maybe at the same time make a fortune.

Shy Sadis and Derek Anderson: The Joint

It’s a little more than three weeks before the licensing window opens when Shy Sadis and Derek Anderson drive up to a dowdy two-story building on a dead-end commercial road in Kirkland.

“I can tell you right now, it’s not my favorite spot,” says Anderson, a 33-year-old with a salesman’s fast-talking patter and casual business attire: gray slacks, a button-down shirt, and leather shoes.

“It’s got no curb appeal,” adds the blunter Sadis, 40, dressed in jeans adorned with a belt buckle bearing the logo of the medical-marijuana dispensary that he and Anderson founded four years ago, and now hope to convert into a chain of 502 retail stores. “The Joint,” the buckle says, with a pot leaf filling in the “o.”

On the other hand, the building is near I-405, and it’s one of the few spots in Kirkland that meets the 1,000-foot rule.

Sadis stays behind to talk on his cell phone about other prospects while Anderson enters the building through the computer business that occupies the bottom floor. “I’m looking for the owner,” he tells the blonde, middle-aged woman behind the counter. “That’s me,” she says. He says he’s looking for a location to house his business.

“What kind of business are you in?” she asks.

“We’re gearing up to start a 502 business,” he says brightly.

“OK,” she says noncommittally.

But as Anderson keeps talking—working in that he was “born and raised” in Kirkland and that he and Sadis “run their business like a business”—the owner and her husband, who wanders over, seem supportive.

“I just read this morning that 54 percent of Americans support legalizing marijuana,” she says. Her husband adds that he heard there’s a “former Microsoft executive trying to get into the business”—a reference to Jamen Shively, the self-proclaimed “dot-bong” entrepreneur whose grandiose plans, albeit clouded by behind-the-scenes shakeups, have garnered national press. (See “Jamen Shively’s Green Rush,” SW, Oct. 9.)

Sadis, who has since entered, scoffs. The publicity reaped by Shively, whom he considers an opportunistic newbie, is a sore point with him. “We’re the pioneers,” he says. But he doesn’t argue with the couple’s general drift.

Sadis and Anderson are primarily interested in leasing, though the owners reveal that they’ve been trying to sell the building for years. They are well aware of its sudden desirability to 502 entrepreneurs, a flurry of whom have already come by. “They were very interested,” the husband says of one group.

“Here’s our main concern,” says the woman, whose next words explain why she and her husband ask not to be identified in this story. “If for some reason the feds come against this, the building could be confiscated.”

Anderson jumps in to relate that the Department of Justice released a statement in August indicating that it would not move against Washington and Colorado as long as they abide by certain guidelines.

The couple nods. They’ve heard about that. The husband enthusiastically takes the entrepreneurs on a tour of the place, pointing out attributes like cinder-block walls that he says even a sledgehammer couldn’t pierce.

After the tour, the wife reiterates: “Look, we’re getting close to retirement age. We don’t want to have our assets seized.” But she and her husband agree to consider an offer. The entrepreneurs say they’ll be in touch.

Whether or not this building works out, Anderson and Sadis are prepared to move ahead. They have already secured three locations where they can operate 502 businesses, in Tacoma, Snohomish, and Bellingham. They also have two medical-marijuana dispensaries in Seattle, in the U District and Capitol Hill, but those won’t meet state regulations for 502 shops.

In fact, those dispensaries will likely have to close. In late October, a state working group proposed regulations for the medical-marijuana industry that would funnel all legal pot sales through 502 stores. Yet Sadis and Anderson don’t want to give up the Seattle market. So they continue to look for sites in the city and nearby.

The Bellingham location is the one that excites Sadis, and it has nothing to do with market potential. Last year, Bellingham authorities charged him with marijuana distribution after a raid on a Joint dispensary in that city. (Anderson was not charged because his name was not on the paperwork; Sadis says his own ownership stake in the business is much larger.)

Court records say that the raid followed undercover buys at The Joint in which detectives were asked to show proof of authorization by a health-care provider, making the charges somewhat puzzling. However, the documents also note that Sadis acquiesced when one detective offered to sell him pot, which may or may not be illegal depending on your interpretation of the law.

In any case, the cops later came looking for him, first at his home in Mill Creek, then at his son’s baseball game. Tipped off by his girlfriend, Sadis says, he left the game and drove to Bellingham to surrender in court. Sadis never did any jail time and worked out a “stipulated order of continuance” whereby the case will be dismissed in three years if he refrains from future felony marijuana crimes in Whatcom County. The deal does not bar him from opening a 502 store, since that is legal.

“It’s going to be super-sweet the day I open a 502 location [in Bellingham] and shove it in their ass,” Sadis says.

Sadis’ ambitions stretch beyond Bellingham, and even beyond the state. “The Joint,” he says. “It’s super-catchy. I can take that brand anywhere.” He says he’s already registered businesses under that name in Nevada and Illinois, in preparation for what he hopes will be legalization efforts in those states, and has bought the rights to the urls “thejointllc.com” and “thejointcoop.com.” (Thejoint.com has already been snapped up, he explains, by a chiropractor.)

He and Anderson are also discussing ways to get around this state’s three-license limit. They’re mulling a franchise-type operation, whereby friends, family members, and acquaintances would apply for licenses.

LCB spokesperson Smith says “it would be very difficult” to establish such an operation because of rules that require license applicants to declare “true parties of interest,” who are then held to the three-license limit. One suspects, though, that if there’s a loophole, Sadis and Anderson will find it.

The two—both of whom consume marijuana for medical purposes, Anderson for knee injuries related to sporting accidents, Sadis for migraines—met while working in the real-estate industry. Anderson flipped houses before getting “punched in the head by the economy,” he relates. Sadis, luckier, says he became a multimillionaire by buying foreclosed properties and apartment buildings.

In their new line of work, they practice charity. They have made donations to the unions of King County police and Seattle firefighters. (Regarding people who want to give money, “We don’t discriminate,” says the police union’s Bob Casey.) They also participate in the annual Toys for Kids drive hosted by Mariners’ broadcaster Rick Rizzs. (Donate a toy, get a free gram of pot.) Yet they also have a keen sense of the bottom line.

“I’m an entrepreneur,” Sadis stresses. “I’ll sell shit if it makes me money.”

Alex Cooley: Solstice

“This is the little thing that makes us so special,” says Alex Cooley. He’s referring to a document he’s just placed on a wooden conference table in his spare but chic office space on the first floor of a renovated 1927 SoDo warehouse. The prized possession is a certificate of occupancy from Seattle’s Department of Planning and Development, which gives Cooley the right to grow marijuana on the premises.

DPD issued the certificate in March—well in advance of the state’s issuance of 502 licenses and the city’s establishment of zoning regulations specific to the cannabis industry, which it did in October. Cooley—a self-assured 28-year-old with a clean-cut look alloyed by lobe-stretching disc earrings and finger tattoos that on one hand spell LOVE and on the other LIFE—wanted to set up shop sooner than that. And he wanted to do so with the city’s blessing.

So, he says, “We went through the front door of the city of Seattle.” His pitch to DPD, he relates, was “Let us be the example.”

“It was clear he wanted to do everything right,” recalls Brennon Staley, the DPD’s project manager for marijuana zoning regulations. Although the city didn’t have such regulations on the books yet, it did have them for something called “vertical farming.” No one was quite sure what that was since nobody had ever applied for such a permit, but it was intended to promote urban farming that maximized building space. Cooley, Staley says, “made a compelling argument” that his plan for a marijuana production facility fit the bill.

And so Cooley’s company, Solstice, began growing pot in the SoDo space and selling his yield to medical-marijuana dispensaries. He is now avidly pursuing the recreational market. In fact, he intends to grow his business exponentially.

Solstice is the company that Mark Kleiman, the UCLA professor who has served as the state’s top pot consultant, referred to at an August Seattle City Council briefing. Warning of a production shortage in the first year of 502 implementation—given the time it takes to get a marijuana business approved through state and local authorities and then actually grow the plant—Kleiman noted that there was only one already-permitted producer that Seattle could count on.

Solstice’s position has come at considerable cost. As Cooley observes, “It’s expensive being legitimate.” He says he and his two partners planned to spend $80,000 to bring his 9,000-square-foot space up to code: putting in insulation, upgrading the sprinkler system. Instead, the work ate up a third of a million dollars.

“We almost went bankrupt,” Cooley says. They averted that fate, he says, by taking small salaries, reaching into their personal savings, and putting all the money they earned back into the company.

Solstice is now a busy and sprawling operation, with 12 employees occupying three floors, including a mezzanine break room boasting a ping-pong table. The hub of the company, though, is its subterranean level, which devolves into a warren of rooms accessible only by key.

As Cooley heads downstairs to give a tour, the sweetly cloying odor of pot becomes detectable, albeit not overpoweringly so due to the carbon filters the company has installed. Stop one is a garage-sized room where five workers—all men in their 20s or early 30s, who found their way to Solstice through word-of-mouth or ads the company has placed on Craigslist and Monster.com–are breaking down plants into bud-heavy branches and hanging them on racks where they will dry for five to seven days.

“See how few leaves there are, how swollen the bud is?” Cooley asks, holding up one such branch. Those qualities, aesthetically pleasing to buyers and thought to increase potency, are part of what allows the entrepreneur to sell his product as “premium” cannabis. Temperature, humidity, and carbon dioxide exposure are all factors Solstice plays with to achieve them, and to prevent mold and other hazards.

We next go to what Cooley calls a “clean room pass-through,” a changing area where we don white lab coats before heading into the “donor room.” There, cuttings from other plants grow on racks until they’re big enough to make it into the “vegetative room.” They’ll eventually get transferred to yet another room reserved for plants that are flowering. It takes between four and a half months and a year for a cutting to reach this stage.

Cooley points out plants of the “tangelo” and “blueberry cheesecake” strains, which are supposed to smell like their namesakes. (The tangelo really does, the blueberry cheesecake not so much.)

Then it’s back upstairs to the “safe room,” where processed buds and joints are kept under lock and key. “As you can see, there’s very little in here,” Cooley says, opening the safe to reveal only a few vials. That’s because Solstice sells out almost immediately to the 15 dispensaries he supplies, including the Northwest Patient Resource Center, which is aligned with ex-Microsoftie Jamen Shively.

Dozens more want to buy his marijuana, but, he says, “We can’t keep up.”

Cooley, who went into the marijuana business after a hiring freeze prevented him from finding a teaching job in Seattle, and who cultivates a progressive corporate image as carefully as he does his crops, says he’s also choosy about whom he sells to. “Our ideologies have to align,” he maintains. Solstice’s ideology, according to Cooley, is environmentally conscious, pro–Fair Trade, and LGBT-friendly, although he admits a dispensary’s policy on, say, gay rights doesn’t always come up.

Solstice is now planning a major expansion as the recreational market comes online. He is applying for three producer and three processor licenses. If the company gets all of those, it could have six separate facilities in addition to the SoDo operation. Despite its unique status as a city-approved, 502-ready facility, Cooley says he might reserve it for the medical market, a possibility he is entertaining due to the intricate details of state regulations. Most notably, the LCB is stipulating that producers and processors cannot work with marijuana plants they already have. Rather, to preserve the integrity of a “traceability” software system that will keep track of pot products from “start to sale,” entrepreneurs must bring new seeds and starter plants onsite within 15 days of starting operations under a state license.

“We’d have to close down for a time,” Cooley says. “It would cost us a half-million to a million dollars to transition. We might as well take that money and build another facility.”

On the downside, if the legislature decides to do away with dispensaries, the SoDo facility would be left without a clientele. The company is weighing its options and studying what Cooley says is a 1,000-page spreadsheet of data analyzing marijuana growing conditions around the state.

Meanwhile, it is wrapping up a private offering to raise funds for a build-out. He won’t say how much money Solstice is seeking, but discloses that a planned second offering, after the company gets licensees and has more value, will go after a larger amount.

Cooley keeps his cards close to his vest. For many months, he avoided interviews with the press, and when we first met, in late summer, he didn’t let on that he was likely to septuple the size of his operation. More, obviously, will become evident in time.

“We’ve got a one-year, three-year, and five-year plan,” he says.

Molly Poiset

Molly Poiset was learning how to make pastries at a Cordon Bleu school in Paris when I-502 passed. The school was a career turn for Poiset, who had spent many years as an interior designer for wealthy clients in the Colorado ski resort town of Telluride.

Among the many reasons it was an interesting move was that Poiset has celiac disease, which prevents her from eating gluten. She says she wanted to learn to cook pastries the French way so she could adjust the recipes to exclude flour.

When Washington and Colorado legalized recreational marijuana, she realized she could tinker with the recipes in yet another way. Her idea: to create high-end, French-inspired, beautifully decorated and packaged pastries infused with marijuana.

“A lot of people who know me would say, ‘What the . . . ?’ They would not see it coming,” says Poiset, a petite 58-year-old grandmother who prefers wine to pot. But she had a clientele in mind that she cared very much about: well-educated, professional, conservative people. People, that is, like her daughter.

Three years ago, her daughter became severely ill with leukemia. Poiset learned, though a family support group she joined, that marijuana might help. But, she says, “the subject couldn’t be broached.” She felt sure that her daughter would never consider pot.

Following a stem-cell transplant, her daughter is doing much better, but Poiset is continuing her mission to create cannabis fare so enticing that her daughter and others like her would try it. That, Poiset believes, makes her stand out in the industry.

“Right now, anybody else who’s in the business of what we call ‘medibles’ are doing Rice Krispie treats, suckers, gummy bears,” she says. “They’ll take fortune cookies and dip it in chocolate that’s got some cannabis and call it dessert.”

The question she faced while in Paris was where she should relocate to. Despite hailing from Colorado, she quickly realized that Washington was the place to be. Colorado is giving its first recreational marijuana licenses to existing medical operations, while Washington’s process is open to all comers.

Poiset found a condo in an old Queen Anne high school-turned-condominium complex that reminds her of Paris, with its stately architecture, urban feel, and courtyard fountain decorated by sculpted lions. She turned the living-room space into an expanded kitchen, lining shelves against one wall with French-style pots and pans. “They’re very different. They have no bottoms!” she says, holding up one circular metal pan in which you can allegedly bake a cake.

She filled another wall with two clocks, one set to Seattle time and one to Paris time, and giant blackboards, on which she writes recipes that she tries out on the wooden table in the center of the room. To use in her creations, she grows marijuana in a pot, as she does lavender and rosemary.

“I’m on this huge learning curve,” she says one late August day at the table in her kitchen. She is dressed in an elegant long blouse cinched with a belt over white pants. Opera music is playing in the background.

She says she’s still experimenting with recipes—although she tastes her creations only before she infuses them with marijuana, not after. “It’s not my thing,” she says of pot, and anyway she doesn’t want to get “baked” while she’s working. For that pleasure, she employs experienced pot users as taste-testers.

Meanwhile, she is trying to get up to speed on LCB rules, the contacts she should know in the industry, and the Seattle neighborhoods where she might locate her business. The state does not give her the option of operating out of her home.

By early November, she still hasn’t found a place. Agents and landlords, desperate to prove their liberal credentials, will say things like “We voted for Obama,” Poiset says. And then they’ll hang up on her. But she’s confident that some leads will come through.

In the meantime, her plans are firming up. She knows she’s applying for a producer as well as a processor license. “I need to be in control of the supply chain,” she says, explaining that she wants to cultivate marijuana strains that are known for medical rather than psychoactive properties.

She won’t be able to market her goods with medicinal claims; that’s forbidden by state rules. But she notes that the LCB will allow entrepreneurs to run a website about the medical side of pot as long as it is unconnected to their businesses.

Producers and processors cannot get retail licenses, so Poiset will have to sell her pastries to the public through other outlets—all 21 of them, she notes with a wry laugh, referring to the maximum number of stores allowed in Seattle. She says she won’t be able to go much further afield to reach more stores because of yet more rules that prohibit using delivery people outside of one’s business.

In September, Poiset earned an accolade that should help her market herself. Every year, the magazine High Times hosts a “Cannabis Cup” awards ceremony in Seattle, with categories like “Best Sativa” (referring to one type of marijuana plant), “Best Concentrate,” and “Best Edible.” In this last category, Poiset entered a cannabis-infused white-chocolate truffle laced with frankincense and edible gold. She says she wasn’t expecting a win, in part because of her outsider status in the industry, which was reinforced at the event, held in a Fremont banquet hall. “Everyone looked very young and had many tattoos,” she recalls. She says her contrasting presence made her think of the Sesame Street song “One of These Things (Is Not Like the Others).”

When the winners were announced, she recalls, “I was way, way in the back.” So when she heard she won second place for her truffle, she had to elbow her way to the front, repeating “Excuse me, excuse me.” She was thrilled.

Ed Stremlow, Lara Taubner, Randall Oliver, Brenton Dawber, John Brown: Analytical 360

Sir/ Madam,

I am a French student in biological engineering at the University of Technology of Compiegne. As part of my studies I am looking for a six-month internship as an engineering assistant. I have attached my CV.

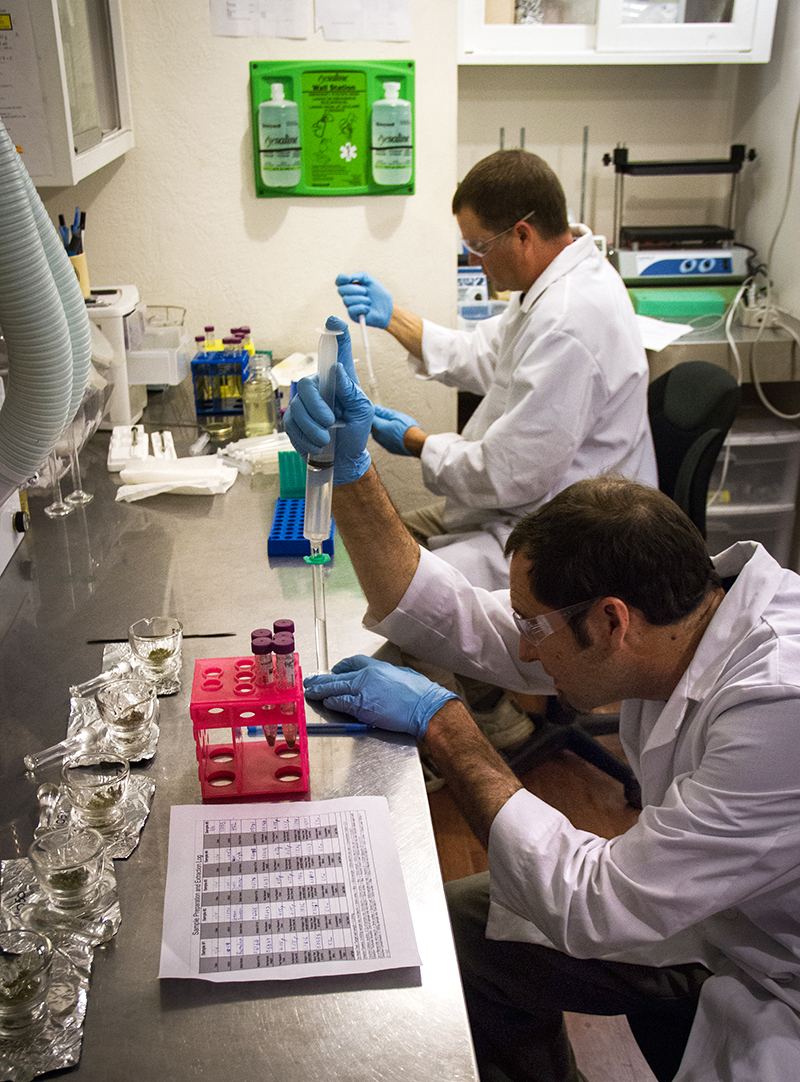

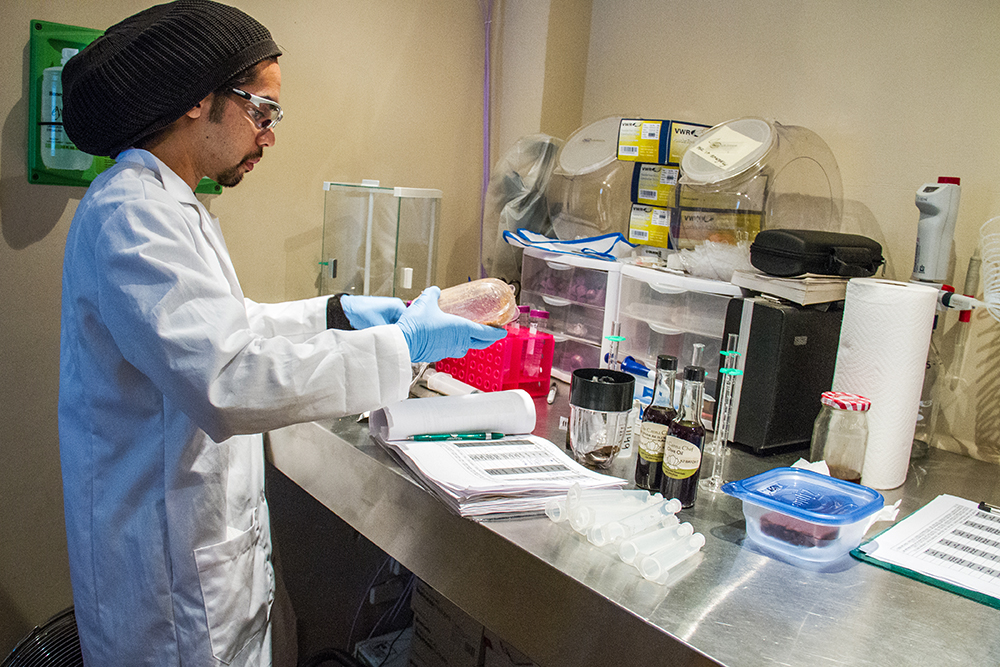

So begins an e-mail from a French native to Analytical 360, which occupies a marijuana-industry niche that has emerged in the past couple of years. The company is a laboratory that tests marijuana, both for potency and for pathogens like mold.

Showing me the French student’s e-mail on his computer in Analytical’s Wallingford office, COO Ed Stremlow chuckles. He’s grown used to such inquiries. He gets so many that he routinely turns people away. And of those he hires, he says, “I haven’t had an intern yet that didn’t want a job here.”

Take Virginia Webber, a Bastyr University graduate who planned to go into quality-control testing on herbs until she went into a dispensary and saw “budtenders” picking up marijuana with their hands—“without even using something like chopsticks,” she says. “I realized how much the movement needs education.” She started as an intern and is now Analytical’s quality-control manager.

Or Caitlin Reece, who last year got a B.S. in environmental science from Evergreen State University. Believing that marijuana is a safer medical treatment than many pharmaceutical drugs, she applied for an internship; was told by Stremlow that there was a long waiting list; sent an application anyway; and scored a position. Her attention to detail in repetitive tests singled her out as a “rock star,” Stremlow says, and she is now the company’s lab manager.

A marijuana testing lab might seem an unusual career path for young scientists, but they are likely reassured by the presence of veterans. Most notable is Lara Taubner, a biochemistry Ph.D. who this fall quit her job as a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Montana, where she studied mad cow disease in a federally funded lab, to devote herself full time to being Analytical’s chief scientist.

She says she was persuaded to leap from academia into the decidedly more turbulent world of marijuana after looking at the research on the drug’s medicinal effects. Frequently discussed is the drug’s usefulness as a cancer treatment. What’s more, she says, “there are definitely ideas out there that cannabis can help prevent diseases like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, even diabetes.”

She would like Analytical to someday move into medical research. Yet she also saw a more immediate need in the marijuana industry: making the drug safe and reliable. “That’s basically a scientific endeavor,” she says. Her husband, Randall Oliver, who with a B.S. is less academically credentialed than his wife but has worked for many years testing compounds and designing processes for pharmaceutical companies, was also enthusiastic about the idea—as were three Seattle-based friends of theirs, including Stremlow, who were itching to try something new with their careers.

“You hear horror stories of patients who have eaten something [infused with cannabis] and gotten sick or slept for the whole day,” says Stremlow, a former real-estate appraiser.

So with the backing of their friends, Oliver and Taubner in 2011 started a marijuana testing lab in their Montana basement, devoting their spare time to the endeavor. They and their three co-founders eventually moved the business to Seattle to cater to the thriving medical-marijuana market here. Other than Northwest Botanical Analysis, founded around the same time, there were no other marijuana testing labs here at the time.

The Stone Way space Analytical moved into is compact. A small lobby, decorated with Kandinsky prints, leads to a couple of back rooms. There, marijuana samples are photographed with a microscope that scans images into a computer, and then tested. Reece explains how a machine called a vortexer spins the samples really fast to facilitate the extracting of cannabinoids, marijuana’s active compounds. Then they can be analyzed with hulking equipment, which resemble several fax machines piled atop each other and utilize a method of quantifying compounds known as high-performance chromatography.

The results do not always please customers. On this August day, a representative of a California-based company that makes a marijuana-infused soda comes in to discuss the disturbingly low potency Analytical’s tests have revealed. “He’s getting 18 milligrams of THC,” Stremlow explains, referring to pot’s psychoactive compound. “He was expecting 72.”

The representative, wearing argyle socks and sunglasses perched on his head, huddles by a computer with Analytical CEO Brenton Dawber to go over the test results. Dawber speculates that the THC is getting stuck around the bottle tops because of insufficient use of an emulsifier. The soda rep takes it in.

Stremlow, who joins them, tells the rep that he knows that the California company’s salespeople have been bad-mouthing the lab. If it doesn’t stop, Stremlow warns, he’s going to bring in all the lab’s clients—some of them dispensaries that buy the soda—and set the record straight. “I don’t think you’ll have many accounts left,” he says.

The rep, seemingly convinced by Dawber’s presentation, diffuses the tension. “I’ll let my sales guys know to correct their verbiage,” he says.

Afterward, Stremlow says that he’ll have to take an even harder line when the recreational market comes online. “I’m not going to tell them how to fix their product. They’re going to have to pay for that.”

Analytical plans to seek state accreditation so it can operate under 502, which obliges the lab to make certain investments. For instance, it has had to buy expensive new equipment that can perform additional tests required of marijuana entrepreneurs, such as those looking for pesticides. The question now is where to put the equipment.

Needing more space, the lab found a building in Georgetown with receptive owners. The owners’ bank, however, threatened to call in its loan if they rented to Analytical. For months, the owners have been trying to find a bank that will refinance the loan. Meanwhile, the equipment is sitting in storage.

While banks have been squeamish, others have expressed interest in investing in Analytical. Over lunch at the Tutta Bella down the street from their Wallingford offices, Stremlow and Dawber recall how a couple of retired guys with money to spare took them to dinner at nearby Blue Star Cafe & Pub.

“They had been in gray markets before,” Dawber says.

“Strip joints, porn shops,” is Stremlow’s recollection. At the end of the evening, Analytical’s founders concluded the retirees were more interested in reminiscing about old times than about putting down hard cash.

No matter. Stremlow says he and his co-founders are wary of giving up an ownership stake to investors, even though the lab’s biggest challenges may lay ahead. As the 502 era gets underway, Analytical founders are expecting a surge of new labs.

“Only the strongest will survive,” Stremlow says. “We hope we’ll be one of them.”