For a man whose suicide was unequivocally confirmed and his case then closed—slammed permanently shut by police, it seemed—Kurt Cobain has been a lively corpse.

He will live again next week, reincarnated by fans and the media for the 20th anniversary of the rocker’s Seattle death by double shots of heroin and Remington. Already, “new” 22-year-old photos of the trashed Los Angeles apartment he shared with wife Courtney Love have been released in some sort of tribute.

Cobain was up and moving around last week as well, when reports of his demise were again called into question following the release of “new” 20-year-old photos from the Denny-Blaine neighborhood death scene. He was still dead at 27, but perhaps a little less so than the week before.

Seattle Police seemed puzzled by this latest stirring. “Despite an erroneous news report,” SPD tweeted to the media and others on Thursday, “we have not ‘reopened’ the investigation into the suicide of Kurt Cobain.”

The famously dead are always restless and closely watched for new signs of life. But SPD insisted this was not such a case, despite a KIRO-TV tweet that said the death case was in fact being reopened.

“Our detective reviewed the case file anticipating questions surrounding the closed Cobain case as the 20 yr anniversary approaches,” nothing more, the department said in a second tweet.

KIRO and the rest of the media then updated Cobain’s death status to being “re-examined.” But even to that, police gave a funereal response.

The detective “dug up the files and had another look, and there was nothing new,” police spokesperson Renee Witt told The Seattle Times. “No change, no developments, no new leads,” she also told The Washington Post.

Yet there was something new: four rolls of undeveloped film. Detective Mike Ciesynski had discovered them while rummaging through an evidence locker a few weeks earlier during his file-foraging, police said.

The April 8, 1994, photos were developed and turned out to be evidence from the death scene. While some were duplicates of earlier released photos and others were gruesome splatter shots of the 138-pound Nirvana frontman, two were important enough to be released to the media and public.

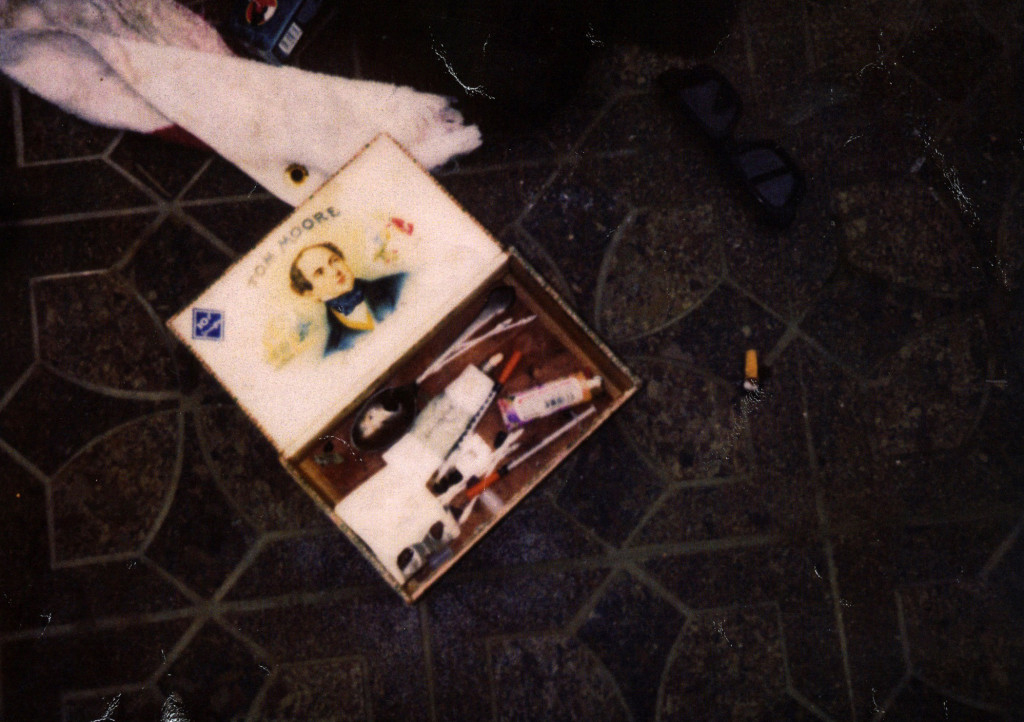

Posted on the police website, one shows an opened vintage Tom Moore cigar box containing Cobain’s apparent stash of heroin and his works—a spoon and a needle collection. The other shows the box closed, next to a small wad of cash, a pack of smokes, shades, some clothing, and a wallet with Cobain’s ID.

“Nothing earth-shaking,” as Witt put it.

Not to her or the police, anyway. But doubters, disbelievers, and murder-conspiracy theorists felt a slight temblor. Just as they were coming down from the retraction of the “reopened” suicide case, they suddenly learned through the police denial that never-before-seen evidence had just been found.

The pictures might not show much. But their discovery was telling: In a case that police say they thoroughly examined before closing, they had overlooked photos from the scene itself.

That seemed to raise other questions, starting with “What else did they miss?” And if the case is in fact closed, why was a detective going over it again and looking through the evidence?

If, as police say, the case is solved—and Cobain was the killer—why the review? Why not stick to information given out in the past?

Why open that Pandora’s cigar box?

The Kurt-Was-Murdered phenomenon is a cottage industry of books, music, websites, and movies, including a film set for release this year, Soaked in Bleach—essentially private detective Tom Grant’s view of how Cobain died.

He questions Cobain’s suicide note and cause of death, and believes that widow Love and live-in male nanny Michael Dewitt were involved in a conspiracy that resulted in murder.

Not that he can prove it. But you don’t need conclusive evidence to believe in conspiracies. A fertile mind will do.

Which is why Seattle Police, attempting to kill off such talk, ended up giving it new life in living color last week.

As even Detective Ciesynski, still trying to rub out the murder theorists, concedes, “Sometimes people believe what they read—some of the disinformation from some of the books—that this was a conspiracy.”

But “that’s completely inaccurate,” he adds. “It’s a suicide. This is a closed case.”

OK, starting now. Or week after next, maybe.

randerson@seattleweekly.com

Rick Anderson writes about sex, crime, money, and politics, which tend to be the same thing.