The two things that can be found anywhere in Seattle are absurdly priced housing and flyers for Fantasy A.

Ever since I played the villain in his upcoming film Fantasy A Gets Jacked, I have been getting frequent calls from the local rapper, who is autistic, asking for my help on everything from editing his writing to staking out a bench for his 6 a.m. birthday beach party (it was a blast). When he called me last month explaining how terrible his current housing situation is and how much difficulty he’s been having navigating Seattle’s low-income housing market, I agreed to help.

Though his flyers are visible all over Seattle, Fantasy A actually lives in Skyway, in a rundown house with a hole in the roof and an infestation of rats, ants, and mold. “I’ve only seen the rats a couple times,” says Fantasy A, whose real name is Alexander Hubbard, “but they’re big and I can smell rat-smell everywhere.” The house has not been maintained since both his parents suffered debilitating strokes. His case manager told him he needs to find a new place to live, but nobody knows where that should be.

All roommate offers fall through. In general the people he hangs out with around his neighborhood and on the street while putting up flyers are not in a position to help. In fact, many of Fantasy A’s friends come to him for assistance. Most of them are disabled people who want to rap and look to him for insight on making beats and writing lyrics. His most notable protege is a 32-year-old neighbor named LG who has worn a mask made of construction paper and duct tape ever since he was called ugly in high school. Fantasy A isn’t good at reading facial expressions, so the mask doesn’t bother him. “LG don’t want to live no more because nobody likes him, but I do things with him and that makes him want to live,” Fantasy A says. One of Fantasy A’s major concerns about moving away is what will happen to LG (he says he has talked him out of suicide on several occasions), but he still desperately wants a place in the city.

As it is, he doesn’t live anywhere near his three jobs (concession-stand lead at CenturyLink Field, mailroom clerk at the Starbucks Center, and audio/visual assistant at Microsoft), and the suburbs are not a good mix with being low-income. According to a study from the Brookings Institution, suburban poverty has increased 65 percent since the year 2000, but suburban communities still lack the resources to accommodate this change, such as reliable bus service and convenient food banks, which are readily available in the city. Fantasy A frequently has to take a Lyft home from the stadium when the buses stop running at night, which eats into his minimum-wage paycheck.

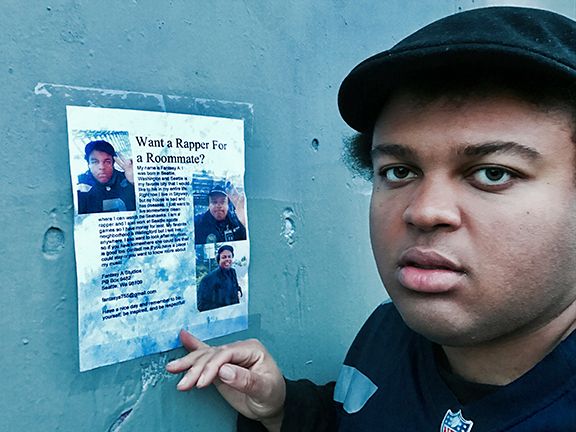

I joined Fantasy A on his trip to the Central District, where he put up flyers asking “Want a Rapper for a Roommate?” This was Fantasy A’s first neighborhood, before rising housing prices forced his family to move to Skyway. As he posts the flyers, I ask him what he thinks about all the white people taking over a neighborhood that was once majority-black. “Well … ” he pauses, trying to come up with an answer that doesn’t sound negative. “It looks weird at times.” He dislikes gentrification, but isn’t personally attached to the Central District, because it holds too many bad memories for him. While canvassing, he tells me about a night in middle school, after he’d moved to Skyway, when he says his father hit him—not for the first time—and Fantasy A hit him back. He had to come back to stay with relatives in the Central District. When he finally went back home, his father, who worked as a gravedigger, started insisting that he no longer wanted Fantasy A living in the same house as him.

“Then he had a stroke and he don’t care if I’m in the house or not anymore,” Fantasy A says. “He don’t care about anything now that he can’t dig graves at the graveyard in Northgate like he used to.”

Fantasy A’s quest to cover the entire city with flyers started because he was looking for a positive reason to spend as much time away from home as possible. Spending all his non-working hours walking around the city helps him clear his head and not think about his tense relationship with his father. “I guess I like him now,” he says with a sigh while putting up the last “Want a Rapper for a Roommate”? flyer. “But being around him still gives me a lot of anxiety. I feel anxiety all the time, but because of my disability my face can’t show it.” Considering that he has been using this method for years to promote his novels and rap albums, but averages only 20 to 30 YouTube hits per video, it seems unlikely that we’re going to find housing this way. To make progress, we have to seek out a housing expert.

Photo by Noah Sofian

To his opponents, Roger Valdez of Smart Growth Seattle is just a shill for developers. To his supporters he is a rare voice fighting to make things as easy as possible for development in a city facing a housing crisis. To get to the bottom of why Fantasy A can’t find a place to live, we meet with Valdez at the coffee shop down the street from the 150-square-foot North-Korean-style microunit he rents for $1,300 a month. If the price weren’t so high, Valdez’s place would be exactly the kind of thing Fantasy A’s looking for, since he doesn’t care about size. “I just want a clean place where I can watch the Seahawks.”

Valdez refers to the coffee shop we’re in as his “living room,” and like Fantasy A he does not spend a lot of time at home, choosing a “Your home is the city, your apartment is just the bedroom” approach to life. Valdez says there are probably thousands of people like himself and Fantasy A who just want the bare minimum of a place to sleep, watch the Seahawks, and shower. However, in recent years, Seattle has placed tighter and tighter restrictions on microhousing, out of fear that by packing a lot of people in a building, developers will put stress on neighborhood amenities like parking. In sum, the regulations have effectively outlawed microunits.

This, Valdez says, is the problem with Seattle housing policy: It too often prevents developers from taking steps that would actually bring down apartment prices. The city does direct millions of dollars toward affordable housing, but Valdez argues that the problem with this solution is that, when low-income-housing nonprofits get a hold of subsidy money, they tend to overbuild and make the apartments larger than they have to, thus accommodating fewer units and giving fewer people access to housing. (Personally I’ve only seen one affordable-housing unit, in Plymouth Housing’s St. Charles building, and it’s so tiny I have no idea how it could be made smaller. The bed alone looks like something out of The Hobbit, and the tenant told me he slept with his legs dangling over its edge.)

Regardless of size, subsidized housing does cost an extraordinary amount to build. The Plaza Roberto Maestas project on Beacon Hill and the 12th Ave Arts project on Capitol Hill collectively cost $92 million to create 200 units of low-income housing. You would think that the same amount could have just been spent on voucher programs to help pay rent in existing buildings.

Fantasy A has already looked into voucher programs, and when we met had his fingers crossed to be picked for Seattle Housing Authority’s Housing Choice Voucher program in February (previously known as Section 8). He later learned he was not waitlisted.

We both thought Valdez made some good points, but after leaving the coffee shop I called former Seattle City Councilmember Nick Licata, a longtime affordable-housing advocate, to get the other side of the story. Licata also thinks Seattle could do better creating affordable housing for people, but thinks the government should have a larger role in its creation. When Licata was on the Seattle City Council, he was a strong proponent of so-called “inclusionary zoning” rules that require developers to set aside a certain number of affordable units when they build new apartment buildings. For a while now, Seattle has had inclusionary zoning laws, but developers can semi-weasel out of them by building the expensive apartments in Queen Anne and their mandatory low-income units in Rainier Beach, thus abetting the city’s economic stratification. Last year Seattle created a new type of housing, called Mandatory Affordable Housing, that would require developers to set aside affordable units in every new apartment building—or pay into the city’s affordable-housing fund. That program could get a test run in the U District with new zoning laws passed by the City Council in late February, but it’s still unknown how well it will work.

Affordable housing north of the ship canal is especially appealing to Fantasy A, who grades all Seattle neighborhoods according to how long they let his flyers stay up and how many people recognize him there from the flyers. The best neighborhood by both metrics, he says, is Wallingford, which is why he wants to live there. The worst is Rainier Beach, which he no longer goes to after getting punched in the chest by somebody who said they were in a gang.

While Licata, unlike Valdez, thinks the government should play a central role in creating affordable housing, he’s also found creative ways to find cheap housing for himself. This includes a stretch in a commune. “25 years,” he says. “Longer than I’ve lived anywhere else, including my parents’ house.” He would consider trying collective living again, but doesn’t think his wife would like it. “If she ever kicks me out, maybe I’ll be back in a commune somewhere.”

Fantasy A had not yet considered the idea of communal housing, but as a people person he’s instantly receptive to the idea. As it happens, I know of a housing collective in Seattle that usually has openings, and it is owned and operated by a local politician, no less. I offer to bring Fantasy A by, and he likes the idea.

Photo by Noah Sofian

To most Seattle voters, Goodspaceguy is just a mysterious name that appears on the ballot each election season. Between campaign cycles, he spends most of his time at his tract house in South Seattle with two Trump-Pence signs in the front yard. Here he likes to feed squirrels, work on his never-ending sci-fi novel, and perfect communal housing with his seven roommates.

With part of his income coming from a string of rental properties around Tacoma, Goodspaceguy is far more conservative than Nick Licata when it comes to government involvement in housing. He first became an advocate for total free-market development while going to college in Stockholm during the 1960s, when he had to live out of his car for a while because Swedish rent-control laws made it impossible to find an apartment. As the BBC reported last year, the average wait for an apartment in Stockholm is still 10 to 20 years, since government controls make the incentive for development next to zero.

Goodspaceguy can’t stand feeling alone, which is why he offers affordable rents in order to pack his house with as many roommates as possible. Fantasy A could be one of those people, which is why we’re in Goodspaceguy’s living room among the stacks of VHS tapes and books written in French, Swedish, and German to discuss the Seattle housing crisis. In his thick Minnesota accent, Goodspaceguy explains that the crisis is only temporary, and ultimately all issues related to zoning and vouchers will pass once the bulk of humanity lives in outer space. It is our next major leap, just as life made the leap from living in the ocean to walking on land. Goodspaceguy imagines rich individuals will build pods that will be launched into space and form together into small villages, and later cities. By obeying the laws of the free market, we will not only colonize other planets, but, more important, the space between planets, so humanity will literally begin to fill the entire universe.

While Fantasy A does not want to live any further from Seattle than he already does—especially not in planetary orbit—he appreciates that Goodspaceguy is talking to him in a non-condescending way and asking him questions directly instead of through me as though I’m an interpreter. At no point in our conversation does either notice anything unusual about the other. They really hit it off, and it looks like they’re going to be housemates. However, it turns out Goodspaceguy requires his tenants to own a car because his South End neighborhood is not friendly to pedestrians. When Goodspaceguy gets a new roommate, he wants them there forever (one roommate has been with him for more than 20 years), and experience has taught him that if people don’t have cars, they don’t stay. Fantasy A doesn’t drive.

By the time we leave Goodspaceguy it is night, so we take a Lyft back to the stadiums downtown where Fantasy A can get his bus back to Skyway. While going over the West Seattle Bridge, Fantasy A’s attention is glued to all the lit windows in the Seattle skyline. It would be a crime if any of those windows had an empty room behind it.

Goodspaceguy had some good points about space colonization, but we don’t need to leave King County, much less Earth, to colonize empty space. According to The Seattle Times, an estimated 200,000 bedrooms county-wide sit empty, any one of which could reasonably house Fantasy A for $500 a month.

We get out at Safeco Field, and Fantasy A eyes all the bare utility poles lining the dark, totally abandoned streets. “I don’t want to go home yet,” he says, pulling some flyers out of his bag, getting ready to canvas. “This is Fantasy A’s city and everybody is going to know who he is.”

news@seattleweekly.com