Stable housing is critical to reducing recidivism among the formerly incarcerated, reentry experts say. Yet, discriminatory housing policies have posed a barrier to the 30 percent of Seattle residents over 18 with arrest and conviction records, and the seven percent with felonies, according to the Seattle Office for Civil Rights. A new city ordinance that prohibits landlords from turning away applicants with criminal histories could change that.

The Fair Chance Housing law implemented on Monday, Feb. 19 was the culmination of years of community organizing that dovetailed the “Ban the Box” movement, an international campaign to end discriminatory hiring practices that target formerly incarcerated people. The Fair Chance Housing law bars housing advertisements with language that exclude those with criminal records from applying. People who have experienced or witnessed discriminatory housing practices can now lodge complaints with the Seattle Office for Civil Rights.

“It’s really an issue of social justice,” said the city’s Office for Civil Rights Communications Manager Roberto Bonaccorso. “For many years, people who have served time have found ongoing barriers put in their way. What this legislation does, is try to address in some small way, the bias that has made it impossible for people to start a new life.”

The law was born out of the effort of members from the nonprofit Jubilee Women’s Center (formerly Sojourner Place) who lobbied against discriminatory housing policies in Olympia over three years ago. The Jubilee Women’s Center offers classes, transitional housing and case management for low-income women, many of whom have been barred from housing because of their own criminal records. A group of housing advocates and organizations that provide reentry services in the Fair and Accessible Renting for Everyone Coalition also hosted forums and worked with city officials to address barriers to housing.

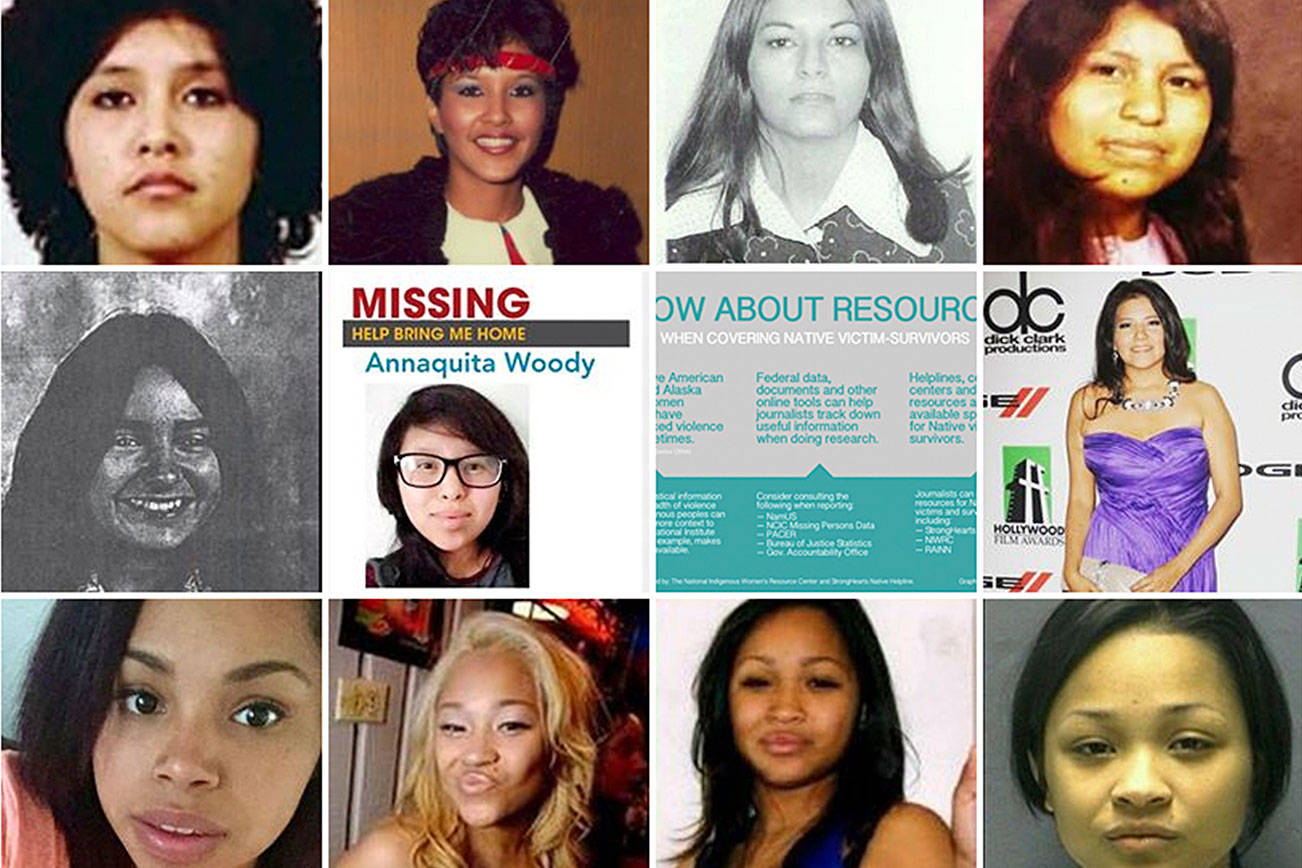

Cheryl Sesnon, the executive director at Jubilee Women’s Center, has seen many women at the center who prostituted or became involved in illegal activity out of survival. “I’ve heard these stories over and over again where they get caught up in whatever the activity is of the people that they’re hanging out with because they don’t have families to support them, they don’t have other places to go, they don’t have money,” Sesnon said, “and then they end up going to jail for them as well.”

Sesnon recalls one woman who visited the center after she’d become addicted to meth and served four years in prison. Determined to change her life upon her release, the woman went back to school with the intention of becoming a paralegal. She needed housing to get back on her feet, but landlords continuously denied her application when they discovered her criminal record.

“She was ready for a fresh start, she had really changed her direction completely and was feeling confident and good about herself. And then when she went to take that step of employment and housing, she just hit a wall and ended up in the same hopeless place that she’d been before,” Sesnon said. Although she didn’t return to drugs, the client did fall into a deep depression, and it took her longer to get back on her feet than it would have if it had been easier to find housing. After she left the center’s housing, the woman eventually found a room in someone’s home and secured a job in a law office. Sesnon said that the Fair Chance Housing law would have helped that client and many others seeking to transform their lives.

“[For] women who are homeless trying to get back on their feet … if they can’t get housing and they can’t get employment, then it just makes it impossible,” Sesnon said.

Barring applicants from housing because of their criminal history just began about two decades ago, according to Columbia Legal Services attorney Nick Straley. “It was only when computer records and court records were readily available online that allowed these new tenant screening companies to aggregate that information and provide it to landlords,” Straley explained. “It was not the case that we had a rash of tenant-on-tenant violence when landlords weren’t able to do criminal records searches.” In fact, empirical evidence shows that stable housing increases public safety, he contends.

Along with reducing recidivism, the law could also help reunify families if one parent has a record, which is all too common. According to the city’s Office for Civil Rights, nearly half of all children in the U.S. have one parent with a criminal record. Sometimes the families have to separate if one parent is barred from housing. “That ordinance goes farther than any place in the country in providing progressive policy and assistance for people with criminal records, because it prohibits landlords from using criminal records for any purpose in making housing decisions,” Straley said.

mhellmann@seattleweekly.com