General William T. Sherman said “war is hell.” If so, perhaps Dante can tell us just which circle of hell Abu Ghraib prison represents. There, McDonald’s fry cooks turn into brutal prison guards who torment and torture their Iraqi charges, smiling all the while.

It raises the question: How could good, all-American kids do such things, much less brazenly document their dirty work?

The second part is easiest to answer: We live in a culture that thrives on the ritual humiliation of reality TV. We’re so obsessed with personal communication that our telephones travel everywhere and record every precious thing we do—”Look, Ma! I’m sodomizing an Iraqi!” By obsessively self-promoting ourselves into celebrityhood—in real time via the Internet, camcorders, mobile phones, and digital handheld personal assistants—we’ve become the Information Age’s compulsive media masturbators. We just can’t keep our paws off ourselves. In this environment, leaving incriminating evidence is inevitable. The surprise, in this culture where the slang word for girl is “bitch,” is that anyone finds it incriminating.

At least the terrible images of Abu Ghraib have restored my faith in the public’s capacity for outrage.

The first part of the question is ages-old. How could good people do rotten things? The families of the Abu Ghraib guards are asking themselves this question. This is not the son or daughter we know, they say.

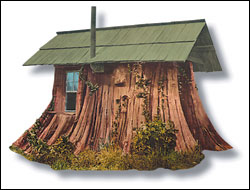

Part of the answer is in human character itself, and the nature of evil. Mossback tends to be a Hobbesian, perhaps because the family tree stump is full of brooding Calvinists who remind me that Man is fallen and deeply wicked.

A more sophisticated view is that we are all capable of both good and evil, containing as we do both light and shadow. Some people integrate these two sides into a human whole via some kind of personal alchemy. Other people are deeply split, like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Some trauma specialists say that splits are not uncommon, nor always undesirable. People in war (and perhaps on spring break) often adopt a survival tactic called “doubling” by which they create a second persona. In this view, those pictures of young, wholesome Americans tormenting prisoners are literally of a different person, one the family doesn’t know. It’s GIs gone wild! When Rush Limbaugh compares the behavior of the American military prison guards to frat boys, he misses the moral point, but he’s not entirely wrong.

We also know “good” people can slide into evil, almost as a matter of routine. Note that in Germany it was civilian doctors and nurses who began euthanizing troublesome patients for the sake of convenience, laying the groundwork for the Final Solution. Small corruptions of any system have a way of being horribly magnified in wartime.

We’re learning that the abuse of prisoners in Iraq was common, widespread, and apparently sanctioned. We also know that these soldiers were performing under enormous pressure—18-hour days, 120-degree heat. Their motto could have been: “Under fire, undertrained, and undermanned.” They were guarding thousands of people who had already been brutalized by their fallen dictator and were further dehumanized by the commander in chief of the occupation. Bush has said repeatedly that all of those not for us are against us, that the terrorists are “soulless,” that we are fighting evil, and God is on our side. That conclusion seems to make sense when we see images of an American hostage being beheaded by his captors.

Can we really expect compassionate treatment of prisoners under these conditions? Yes, actually, but Bush has made that harder with his war rhetoric.

The good liberal in me wants to explain these abuses by finding flaws in the system. But the answer also lies, as good conservatives remind us, in individuals. Some respond to war with brutality, others with character, notably the whistle-blowers who in this case turned in their fellow soldiers. Some GIs held on to stronger, healthier wartime personas and behaved as heroes. Which tells us that we all have the choice to do good if we will only exercise it.

Another case of a “good” person doing evil came to light this week. Neil Goldschmidt, former governor of Oregon, secretary of transportation under Jimmy Carter, and former executive of Nike—a demigod of Northwest progressive politics—admitted to raping a 14-year-old girl back in 1975. Only he didn’t call it that. With a reporter from Willamette Week breathing down his neck, Goldschmidt suddenly resigned from public boards, then confessed to The Oregonian about what he called an “affair” with the daughter of a family friend while he was the mayor of Portland. The Oregonian and wire services picked up this unfortunate characterization—an affair is what two consenting adults have. Nevertheless, Goldschmidt admitted the sexual “relationship” and apologized for the pain and damage he had caused to the victim. The Oregonian‘s readers kicked the paper for permitting Goldschmidt to spin his confession in a way that minimized what had really happened. The fact that public figure Goldschmidt is still spinning suggests he hasn’t come to a real understanding of the crime he—or his other persona—committed. Like the apologies of Donald Rumsfeld and Bush, Goldschmidt’s makes a useful, pro forma start, but not much else. There’s a lot of messy reality still to be faced.