Walking into Pastor Joseph Fuiten’s sprawling Cedar Park Assembly of God church, on a wooded 46-acre plot in Bothell, one can still see a sign of the election—a box holding voter registration forms, emblazoned with a red, white, and blue logo: “For Faith, Freedom and Family: Vote!”

The pastor coordinated the Bush campaign’s state effort to mobilize “social”—read Christian—conservatives and heads a right-wing lobbying group called Washington Evangelicals for Responsible Government (WERG). During the election season, the pastor sent 2,700 such voter registration boxes to churches across the state, netting what he estimates to be 45,000 to 90,000 new voters. Those are huge numbers that are impossible to verify; he says they come from a sample survey of churches that received the boxes. But Republicans and churches are convinced that something important happened among evangelicals locally in this election, just as evangelicals and the “moral values” that concerned them played a pivotal role nationally. “In my 24 years in politics, it’s the most organized I’ve ever seen evangelical churches,” says state Republican Party Chair Chris Vance. He says at many churches there were election coordinators registering voters and then urging them to the polls.

Various local church leaders and religious conservative organizations, including Pastor Ken Hutcherson at Antioch Bible Church and a relatively low-key state chapter of the Christian Coalition, mounted get-out-the-vote efforts this year. Fuiten, though, is seen as driving the new Christian conservative vote. Leah Yoon, a spokesperson for the state’s Bush campaign, now based in New York, credits the pastor with being “single-handedly responsible” for voter turnout among local religious conservatives and calls him “the go-to guy” for this constituency.

Vance exclaims, “Now we’ve seen what he was able to deliver.” He adds that Fuiten is “probably the most active person among evangelical conservatives in the state.” Indeed, not widely known outside evangelical circles before, Fuiten has suddenly emerged as perhaps the leading figure of the local religious right.

“He’s filled a vacuum,” observes state Democratic Party Chair Paul Berendt. After the crushing defeat of 1996 gubernatorial candidate Ellen Craswell, a Christian conservative, Berendt says, the “far right seemed to be dispirited and disjointed” and “more or less left politics.” This election, and Fuiten, brought them back in.

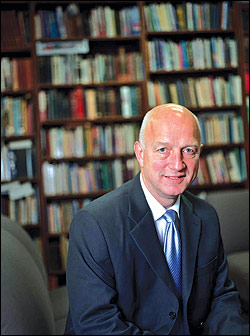

In his book-lined office, wearing a gray suit and exuding a judicious authority, 54-year-old Fuiten could be taken for a CEO or a politician as easily as a preacher. In fact, though he was the child of two preachers, Fuiten initially planned to be a politician, heading a student Republican group at Willamette University in Oregon. He felt called to ministry instead one night in college, when he opened the Bible at random, looking for a sign about his life plan, and his eyes fell on this passage: “They that turn many to righteousness shall be as the stars that shine forever and ever.”

He now presides over one of the biggest megachurches in the state. Cedar Park is not only a ministry, with eight branches throughout the Puget Sound area, but a $13.8 million-a-year, 400-employee corporation. It runs several schools, including K-12 programs at the Bothell main campus, a funeral home, a cemetery, a food bank, and an auto shop, open to the public, which is intended to help low-income folks by charging sliding-scale fees no greater than $59. (He is battling to keep the last two open despite zoning objections from King County.) Noisy construction taking place around mountains of earth across from the main building in Bothell, where new school buildings are taking shape, underline what a bustling operation it is.

Fuiten hews in many ways to the standard evangelical path, stressing if not the literal then the “plain-sense meaning” of the Bible and affirming traditional values of God, family, and country. Outside the church sanctuary, there hangs a display titled “Military Moms,” with pictures of soldiers stationed in Iraq and elsewhere. But Fuiten also has instituted some unusual twists. Believing that Christianity has strayed too far from its Jewish roots, Fuiten has Cedar Park celebrate Jewish holidays, including Passover and the Jewish New Year, Rosh Hashanah, and a painting of dark and curly-haired Jesus wearing a Jewish prayer shawl hangs in a separate small chapel. Fuiten has long incorporated his political interests into his ministry, as well. Every election season, he has had ushers walk down the aisle with voter registration forms and asks anyone who has moved or changed their name recently to raise their hands.

When Vance of the state Republican Party went looking for someone to rally the evangelical community last spring, he heard about Fuiten. “You know, there’s a guy already doing this,” other pastors told him. Both Vance and the Bush campaign asked Fuiten to broaden his efforts on their behalf.

When Fuiten agreed, the Bush campaign sent him a strategic plan. “It was just a dumb policy,” he says. It called for asking churches to supply their lists of members—raising obvious privacy issues—and overtly stumping for Bush among these folks. Fuiten thought he had a better way of doing things. “Just register them to vote,” he says he told the Bush campaign in a plan of his own that he forwarded to the national organization. “You don’t have to tell them how to vote. They’re going to vote overwhelmingly one way anyway.”

As he implemented his plan, he encouraged other pastors to distribute voter registration forms, not just at tables off to the side but within their services. “What you really want—you want the pastor to give the blessing to political involvement,” he says. Contrary to popular belief, he contends, many evangelical ministers view politics with distaste, maintaining that they are in the business of saving souls, not the world. He prodded them and their members into the political arena with a message of urgency that went beyond the presidential race and into what for evangelicals is a touchstone issue: gay marriage.

“Three of the nine [state] Supreme Court Justices who will make the final marriage decision are up for election,” he wrote in an August edition of WERG’s newsletter, referring to the court’s upcoming review of two rulings invalidating the state’s Defense of Marriage Act, which defines marriage as a union between a man and a woman. “If this does not bring Christians to vote, nothing will.”

In his church, on a table next to the voter registration display, Fuiten put a stack of petitions seeking a state constitutional amendment codifying the Defense of Marriage Act. He also helped organize the pre-election rally called “Mayday for Marriage” that drew 20,000 people to Safeco Field. While the pastor did not endorse candidates from the pulpit, which would likely jeopardize the church’s tax-exempt status, he did refer parishioners to a personal Web site that lists his “pastor’s picks” (www.pastorspicks.com). The picks chose virtually every Republican running in a partisan race, including attorney general candidate Rob McKenna, who had quietly assured those concerned that he would vigorously defend the Defense of Marriage Act. Fuiten also gave the nod to gubernatorial candidate Dino Rossi. Although liberals took issue with Democratic candidate Christine Gregoire’s refusal to back gay marriage, Fuiten says that conservatives were upset with her for failing to defend the marriage act strongly enough. For Supreme Court, he supported conservative Jim Johnson and libertarian Richard Sanders.

Given all of Fuiten’s efforts, you might think that he was disappointed in the results. Bush lost the state by a bigger margin than he did in 2000 (7 percentage points this year, versus 5 percentage points in 2000). The pastor finds vindication, however, in the triumph of McKenna and what, as of this writing, is the possible triumph of Rossi. His picks for Supreme Court also won the day.

The court battle over gay marriage, expected to be heard in the spring, is now uppermost in his mind. Fuiten hopes to use his and WERG’s new political base to take on the issue. WERG, which already maintains a lobbyist in Olympia, is about to bring on a second staffer to speak out publicly and develop a grassroots campaign against gay marriage.

Fuiten is savvy to political realities. He knows evangelicals are considered in some circles to be, well, the devil, and though resentful of the fact, Fuiten seems to yearn to get beyond that. Although he supported Craswell, he’s not sure he would again. He brands her campaign as “too extreme.” He feels the Christian right in general is too negative. “You can’t just be against abortion and gays and expect to create a culture,” he says. He has formed an ad hoc group dedicated to what he calls a “positive Christian agenda.” Talking with Fuiten about the agenda, though, it’s hard to discern where the differences lie between him and someone like Craswell. He is against abortion and homosexuality, both of which he classifies categorically as sin. To strengthen families, he supports putting restrictions on divorce. He’s in favor of tough criminal laws and public support for religious and other private schools. He believes businesses and individuals need to be “unfettered” from excessive taxes and regulation. It is, in other words, a quintessentially ultraconservative agenda.

Fuiten is, however, part of a new generation of evangelicals seeking to form alliances beyond their community on common-ground issues such as AIDS and human trafficking (see “The New Abolitionists,” Aug. 25).For a time, Fuiten sat on the Governor’s Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS. How influential could he become? So far, his attempts at alliance building have had mixed success. Fuiten relates a call he made to a lobbyist for a mainline religious organization. “I’d like to find something you and I can work on,” Fuiten said, asking the lobbyist if he could think of anything. The lobbyist paused for a minute, before responding, “No, I don’t think so.”