JULY 30 WAS Do as We Say Day at Boeing. That’s when the company conducted an ethics refresher course for all 75,000 employees of its Integrated Defense Systems (IDS) units in Puget Sound and around the globe. Spokesperson Walt Rice tells Seattle Weekly the company’s ethics have been challenged by “the actions of a few people” and by government investigations that “have served as a poignant reminder of how the actions of individual employees can have far-reaching effects on our business performance.” It could also have something to do with the recent suspension of three Boeing subsidiaries by the Air Force for breaking federal law and the threat that Boeing could at least temporarily be barred companywide from further defense bidding. Putting on a good ethics show can’t hurt, concedes Air Force Undersecretary Peter Teets. “If they immediately start to put in place corrective actions, training of employees, employee hot line, and drive up the integrity down through the organization of these units,” he says, “I would think that their suspension could be lifted” in 60 to 90 days.

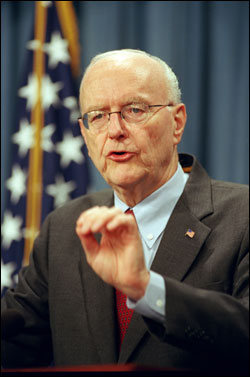

Thus the Lazy B’s offices emptied out last week as everyone from interns to IDS’s chief executive took part in a four-hour retooling that, says Boeing, emphasized “the company’s commitment to the highest of ethical standards and integrity.” Alas, CEO Phil Condit and other top execs from Boeing’s Chicago headquarters didn’t attend. They were still busy trying to explain the corporation’s latest ethical breech, a kind of BusinessWeek version of Mad magazine’s Spy vs. Spy cartoon, a deceit that turned out to be less cost-effective for Boeing’s ailing space and communications divisions than the company might have planned. The possession of 25,000 pages of stolen military-satellite documents from rival Lockheed Martin that helped Boeing win a nearly $2 billion satellite-launch contract in 1998 had suddenly become a $1 billion liability. On July 24, the Air Force, following an investigation into the theft, reassigned much of Boeing’s launch work to Lockheed and indefinitely suspended three Boeing space subsidiaries from competing for new defense contracts, costing the company what could be a record $1 billion in potential revenue. “Boeing has committed serious and substantial violations of federal law,” said Teets, who, despite having once been Lockheed’s CEO, was not smiling. Of course the big companies spy on each other and from time to time rival documents tumble into each other’s safe. But Boeing was getting a stiff sentencethe first major defense contractor suspension in a decadebecause “I have never heard of a case of this scale,” Teets said at a D.C. press conference. He pointed out that Boeing was not exactly forthcoming with the Air Force about the amount of Lockheed data in its possession, following discovery of the theft in 1999, when Boeing informed Lockheed Martin and the Air Force that Boeing found “a small amount” of proprietary information in the hands of an employee. “It was a good, long number of months before any additional

proprietary information was even acknowledged,” said Teets, and it wasn’t until this April that the Air Force received the final documents from Boeing. “It took a period of approximately four years for them to provide us with all of it,” he said.

A PARALLEL CRIMINAL probe of the theft is under way by the Justice Department. A day after the Air Force announcement, two former Boeing employees, onetime Lockheed space engineer Kenneth Branch and his Boeing supervisor, William Erskine, were indicted by a Los Angeles grand jury for having possessed the documents. If convicted, they could face up to 15 years in prison for violating the Procurement Security Act. Boeing had already sacked both, but they maintain they were sacrificed after the company used the documents to win the contract. (Branch says that during a job interview at Boeing in 1996, he showed a Boeing official a report on Lockheed’s rocket project and was hired six months later.) Last week, Boeing denied the purloined documents helped it beat out Lockheed, and in court filings denied Lockheed’s claims in a Florida civil lawsuit that it engaged in antitrust or racketeering violations. If all that wasn’t challenging enough for Boeing’s ethics instructors, it

turns out that a former company chief scientist claims he was fired for blowing the whistle on another satellite division co-worker who had 8,800 pages of separate Lockheed internal documents. At a July 24 hearing in Los Angeles, a judge tentatively ruled that Krishan Raghaven could proceed with his case against Boeing, alleging he was fired after revealing that Dean Farmer, an ex- Lockheed Martin engineer who headed the Boeing satellite business unit, had e-mailed him slides from the “tons” of Lockheed documents in his possession. Farmer, who said the documents were benign and unimportant, was also fired. Boeing, which won’t comment on the documents aspect, claims Raghaven was let go for other causes.

There’s more. Earlier this year, Congress’ watchdog, the General Accounting Office, reported that proprietary information belonging to another defense rival, Raytheon, was found in Boeing’s offices. Boeing had informed the government that members of its 1998 team bidding on the exoatmospheric kill vehicle (EKV), part of the Star Wars II missile-defense system, had obtained and misused Raytheon documents in the processspecifically, a software test plan Raytheon submitted to the Army that wound up in Boeing’s hands. The competition was abandoned after the documents were found, and Raytheon was awarded the contract by default. The government weighed whether to bar a Boeing unit from further contracting and pursue a financial settlement. Even though taxpayers had spent $400 million to develop and test Boeing’s EKV, the feds let it all slide, partly in “the belief that litigation was inconsistent with its partnership with Boeing,” the GAO reported. (Whereas there were 50 defense contractors in 1990, they have merged into five major contractors today, limiting the Pentagon’s options.) No penalty was also the outcome of a GAO investigation last year, which found that Boeing and its missile-defense subcontractor, TRW, exaggerated 1997 test results on a sensor used to identify enemy warheads. Despite problems that caused the sensor to confuse warheads with decoy balloons, Boeing and TRW claimed the $100 million dry run was “highly successful.” Actually, two-thirds of the flight data was useless, said the GAO, and the vehicle’s false-alarm rate exceeded required limits by more than 200 times. Boeing disputed the GAO findings, although none of the contrary data was disclosed by Boeing and TRW to the government until after a whistle-blower complained and the FBI investigated.

CEO CONDIT SAYS Boeing’s latest ethics classes are an attempt to “ensure that Boeing will never again have to face such criticism” like that leveled by the Air Force over the Lockheed theft (not to mention the Air Force’s reluctance to spend $17.2 billion to lease 100 Boeing refueling tankers that could cost taxpayers at least $1.9 billion more than buying the planes outright). Boeing has now hired former Sen. Warren Rudman to lead a review of Boeing’s ethics practices, including, the company said in a statement, “any management or cultural factors that could affect how these policies and procedures are respected and enforced.” Still, Condit says he has asked Rudman “to verify” that the Lockheed theft was what Boeing considers a rare violation of company policy. Well, the other day, a D.C.-based public watchdog, the Project on Government Oversight (POGO), updated its database on defense-contractor violations in recent years and added 14 new instances of misconduct or alleged misconduct by Boeing. That brings the company’s total to 50 since 1990. Adding up the fines, penalties, and costs of restitution or settlement, POGO analyst Eric Miller last week said Boeing’s expenses come to $378,941,913. On POGO’s list, Boeing ranked third. General Electric was first, with 87 instances of misconduct and alleged misconduct and payouts of $990 million. Lockheed was second with 84 instances and payouts of $426 million. From 1990 through 2001, Miller adds, the top 10 federal contractors racked up 280 instances of real or alleged misconduct and paid out $1.97 billion dollars. There were no figures on how much they earned by doing it, but it was hard not to notice that in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer last week, Boeing was reported to have quietly won a contract to develop new airborne warning systems. For the Air Force. For $1 billion. That’s an estimate. Boeing says the Air Force asked it not to make the amount public. Gee, go figure.