Chris Lundquist was 29 when he started working for Heaton-Dainard Real Estate in 2012. He was brought on with the agency because of a personal relationship he had with one of the company’s co-owners, Will Heaton.

His job was seemingly simple, but also important to the business model that Heaton-Dainard would work by.

Lundquist described his job as what was called a “bird dog,” or wholesale finder tasked with searching for low-value properties to be purchased by the agency, invested in, and sold for a much higher price.

The properties that Lundquist was asked to find would be relatively low in value — decrepit houses, homes in foreclosure, tax delinquent homes and even homes with recently deceased owners.

These kinds of properties are valuable to certain real estate investors because they can be purchased for low prices, then flipped and resold for lucrative profit margins.

Lundquist said he was able to find a lot of these properties during the few months that he worked for Heaton-Dainard. He worked primarily in the West Seattle area, where he grew up.

He said getting these kinds of homeowners to sell could be difficult, as often the owners were elderly and did not want to leave a home that was familiar to them.

Lundquist said he figured out that to be good at his job and to convince people to sell their homes to the company, he would have to spend weeks, even months getting to know the homeowners and figuring out what they wanted. He would stop by regularly to visit these potential sellers, putting in the work to gain an edge on his competitors.

But Lundquist said trying to broker a sale with the owner of these kinds of properties was often a “legal gray area” because homes going into foreclosure are legally referred to as “distressed homes” in Washington state.

“Distressed homes” legally require a “distressed home consultant” to be involved in the transaction and to represent the homeowner’s best interests in avoiding the foreclosure and understanding the deals and contracts they are offered for their home.

Washington state’s “distressed property” law is intended to protect distressed homeowners from predatory investors and wholesalers looking to take advantage of their situation in a practice known as equity skimming.

Under state law, equity skimming is illegal, and being identified as having committed a “pattern of equity skimming” can land an offender with a class B felony, according to RCW 61.34.030.

In 2013, less than a year after being brought on as “bird dog,” Lundquist believes he was made to unfairly take the fall for an equity skimming lawsuit involving a Vietnam veteran and the negative publicity it garnered.

‘As long as the price was cheap, they would take over’

Ames Larson was about 67 years old when he met Chris Lundquist. Larson owned a house in West Seattle, a property that Heaton-Dainard was interested in purchasing.

The home was going into foreclosure because Larson owned over $11,000 in delinquent property taxes. Because of Larson’s fixed Social Security income, he could not afford to pay the property taxes he owed, nor could he afford the cost of utilities in the home.

Lundquist said he had spent quite a bit of time with Larson and remembers how cold and dark the home was without electricity. Lundquist approached Larson like he approached most of his potential home sellers — he checked in regularly and built a relationship of trust.

After weeks of effort, Lundquist eventually received a commitment from Larson that he would sell his house to Lundquist and the companies he worked for. After receiving the intent to sell, Lundquist reached out to the Heaton-Dainard partners about closing the deal.

Lundquist maintains that he did not draft the purchase and sale contracts, nor did he negotiate finalized prices for property sales. He said the finalized contracts were brought by someone like Will Heaton or James Dainard, of Heaton-Dainard, or Nick Weaver, of Northwest Home Buyers.

He said as “bird dogs,” they would try to negotiate a non-specific price, typically for as low as possible because the company incentivized low-price acquisitions that could be flipped into high-value developments. Lundquist said once a commitment was made to sell, the investment and development firms like Heaton-Dainard would take most of the control of the transaction out of his hands.

“As long as the price was cheap, they would take over,” he said.

Lundquist said he liked Larson — he respected him as a war veteran and a former prisoner of war. He got the sense that Larson did not always trust people so easily and Lundquist appreciated that he had earned it.

That is why Lundquist said he was both surprised and upset when he found out Larson was suing him and the companies he worked for.

The transaction to buy Larson’s house was suspicious for several reasons. The way the deal was closed was unorthodox and shady, but the bottom line was that the deal looked and smelled like equity skimming, he said.

The contract

The lawsuit that Larson and his lawyer filed did not name Heaton-Dainard explicitly, though it did name Lundquist, his assistant and friend Huy Bui, Will Heaton, and a handful of other companies that Lundquist described as “shell companies,” intentionally written into the contract to “strip money” away during the purchase of the property while also protecting the parent company, Heaton-Dainard, from being implicated in a lawsuit.

The main issue with the Larson property purchase and what Lundquist believes likely triggered the lawsuit was the fact that some of the companies and parties involved in the transaction made more from the signing of the deal than Larson did for his own home. Larson walked away with around $40,000 for the sale of his home after he paid on taxes he owed.

Larson’s home was valued to be worth approximately $300,000. After Lundquist and his employee Huy Bui routinely visited Larson to loosely negotiate a sale through fall of 2012, Larson understood that he was offered $120,000 for his home and accepted the yet-to-be finalized offer, according to the legal complaint.

Larson claimed that on Nov. 29, 2012, Lundquist arrived at his home with a contract for a purchase price of $70,000.

Lundquist said the contract he brought to Larson was emailed to him on Nov. 20, 2012, by Nick Weaver of Northwest Home Buyers.

Five days later, Bui, Lundquist and Dainard showed up to Larson’s house with the closing contract. With less than two weeks until his home was supposed to go into foreclosure, Larson claimed he felt pressured into signing the contract, according to his legal complaint.

After the deal was signed and Larson received $40,000 for a house worth $300,000, Lundquist received a $22,000 “finder’s fee” for making the deal happen, Bui received a $12,500 assignment fee, a company called Sound Real Estate Network made $16,250 and a company called Invest Now made $48,750 in the deal, according to the legal compliant. Lundquist said Invest Now is a company owned by Will Heaton.

In addition to taking issue with the way equity was stripped away from Larson at the purchase, his complaint also alleged that the contract he signed waived his right to a “distressed home consultant,” a legal requirement to help him understand the contract he signed. Larson claimed he was not given copies of the contract, a legally required procedure, and he claimed that the purchase and sale of the property was illegally notarized.

Lundquist also attests to the fact that the transaction was illegally notarized, and he said he was unwillingly made a part of the illegitimate and deceptive move to take advantage of Larson.

Closing the sale

On Dec. 4, 2012, Lundquist and Hui were at Larson’s house waiting on the arrival of Dainard to close the sale.

Lundquist said eventually Dainard arrived and pulled into the driveway with his black SUV. He went out to speak to Dainard before he came inside.

Lundquist was expecting to do a final walk-through of the house with Dainard, and then typically they would go to escrow and get the closure of the sale notarized.

Lundquist asked which car Larson would ride in to get the sale notarized. Dainard told him they would notarize the sale at Larson’s home. Lundquist was confused by this, but did not question the man he worked for.

Before re-entering the house and meeting with Larson, Dainard told Lundquist to take a photo of Larson’s drivers license, a request that Lundquist thought was strange. But nevertheless, he complied with Dainard’s order and snapped a photo of the man’s drivers license with his phone after requesting to see it.

Lundquist said Larson did not really seem to think anything of the request. He said Larson seemed to be in good spirits about the sale of his home and even joked and laughed with the home buyers as he signed the contract to sell his home.

Before leaving the property, Dainard suggested Larson and Lundquist should take a photo together to capture the moment. Neither Lundquist nor Larson thought much of it as they huddled together and smiled for a photo taken by Dainard.

After that day, everyone got paid and the Larson deal was forgotten about — until Bui and Lundquist heard about Larson’s lawsuit against them. It was legal complaint that did not mention James Dainard or Heaton-Dainard.

By Dec. 21, 2012, Larson had filed a lawsuit against Lundquist, Bui, Heaton, Weaver and a handful other companies owned by or related to Heaton-Dainard, including Terrell McGrath and her company McGrath Escrow Inc.

According to Lundquist, McGrath had been a longtime friend and business associate of Dainard. Lundquist believes Dainard used McGrath Escrow Inc. to illegitimately notarize the Larson deal.

He believes the photo he had taken of Larson’s drivers license was used to provide Larson’s personal information to fill out the notary paperwork and to avoid questions or attention as to what was a predatory contract.

Another fact that supports this narrative was that the homebuyers met at Larson’s home on December 4, but the contract was recorded as notarized on Dec. 5 or Dec. 6, and falsely claimed the contract was signed on one of those days by Larson in McGrath’s presence.

Lundquist said McGrath and Dainard had a history of business together and have been implicated in similar lawsuits regarding predatory housing transactions before.

On Dec. 31, 2012, Lundquist texted Heaton, concerned about his business partner Bui, who he said was panicking about the lawsuit.

After assuring Lundquist that Bui would be fine, he texted him saying: “It’s all fixable — you just have to keep bringing in deals.” He punctuated the message with a smiley face.

Lundquist trusted that the people at Heaton-Dainard would do their part to protect them from the lawsuit and the repercussions it would have. After all, Lundquist and Bui had just been doing what their boss had told them to do.

The “bird dogs,” like Lundquist and Bui, were told to target homes going into foreclosure. The employee sales manual for Heaton’s Invest Now instructs their home finders to not only target homeowners going into foreclosure, it also tells them to not “mention” to the homeowner that you know about their foreclosure.

The sales manual urges their associates to ask questions like, “Is your real estate agent familiar with foreclosure?” or “What happens if you cannot get an offer on the house?” These are questions that help the associate understand what kind of leverage investors might have on a homeowner in a desperate situation.

Over the months following the lawsuit, it became clear to Lundquist that the partners at Heaton-Dainard, as well as any of their other companies, were not going to take responsibility, nor would they help protect him.

Early on after the lawsuit, Lundquist and his associates were asked by Heaton-Dainard to file their own LLC’s with the state and accept themselves as legally liable as a result. This was one of the first red flags for Lundquist.

Calls from a reporter

By January 2013, Lundquist had been receiving calls from a reporter for Seattle Weekly who was investigating the lawsuit and those mentioned in the Larson complaint.

Lundquist said he was told by Heaton and Dainard not to answer talk to the reporter. In the end, this move would only serve to hurt Lundquist and to protect Heaton-Dainard. Lundquist said he regrets his decision to ignore the Seattle Weekly reporter to this day.

Seattle Weekly’s article was published on Jan. 11, 2013. Much like the legal complaint itself, it did not mention that James Dainard was at Larson’s house during the closing of the deal, nor did it mention that he was the one that brought and likely drafted the contract.

The article mentioned Heaton, Weaver and their shell companies as being involved because they were named in the legal complaint, but it also frames Lundquist as being one of the sole perpetrators of the predatory deal, despite the fact that he was really just a pawn in the scheme.

Lundquist even believes that Dainard took the photo of him and Larson in the veteran’s home as a way to make it look like Lundquist was the one who orchestrated the deal and not Dainard.

Lundquist was not aware of the article until it started preventing him from making sales with home sellers who read the article and no longer trusted Lundquist.

The Larson suit was settled on June 17, 2013. Lundquist was told by Heaton-Dainard that he would have to pay back the $22,500 finder’s fee that he made from the Larson deal. The money that he owed was informally taken from his future commissions.

There was no contract or structured way for the agency to be paid back by Lundquist. Instead they randomly subtracted amounts from his assignment earnings. Sometimes they would take hundreds from his fees, sometimes they would take thousands.

Things continued to get worse for Lundquist. He had to avoid giving people his full name because of fear they would not work for him. He was losing sales and money, and in late August 2014, he and Bui were fired by Heaton.

The next few years were hard on Lundquist. He went from making good money as a wholesale home buyer to struggling to find a job that would hire someone implicated in an equity theft lawsuit.

Lundquist claims he has since experienced a pattern of potential employers denying him a job because of his alleged involvement in the Ames Larson lawsuit.

Lundquist realized how much of a problem the article was going to be for him, so he reached out to Heaton and Dainard about making an effort to speak with the editorial team at Seattle Weekly and set the record straight about what really happened.

Lundquist was told that lawyers would contact Seattle Weekly regarding the article, but that did not seem to be true. Lundquist continued to contact them about their effort to correct their article, but he only received empty promises and dismissive replies.

Eventually, Lundquist had enough. He felt that he had been completely thrown under the bus. He had lost money, his job and his reputation.

He arranged a meeting with Dainard to demand some sort of way to make the situation right.

Dainard arrived to meet Lundquist and they agreed on a deal. Lundquist would keep quiet about the situation and in return, he would receive $22,500, the exact amount he made in the Larson deal.

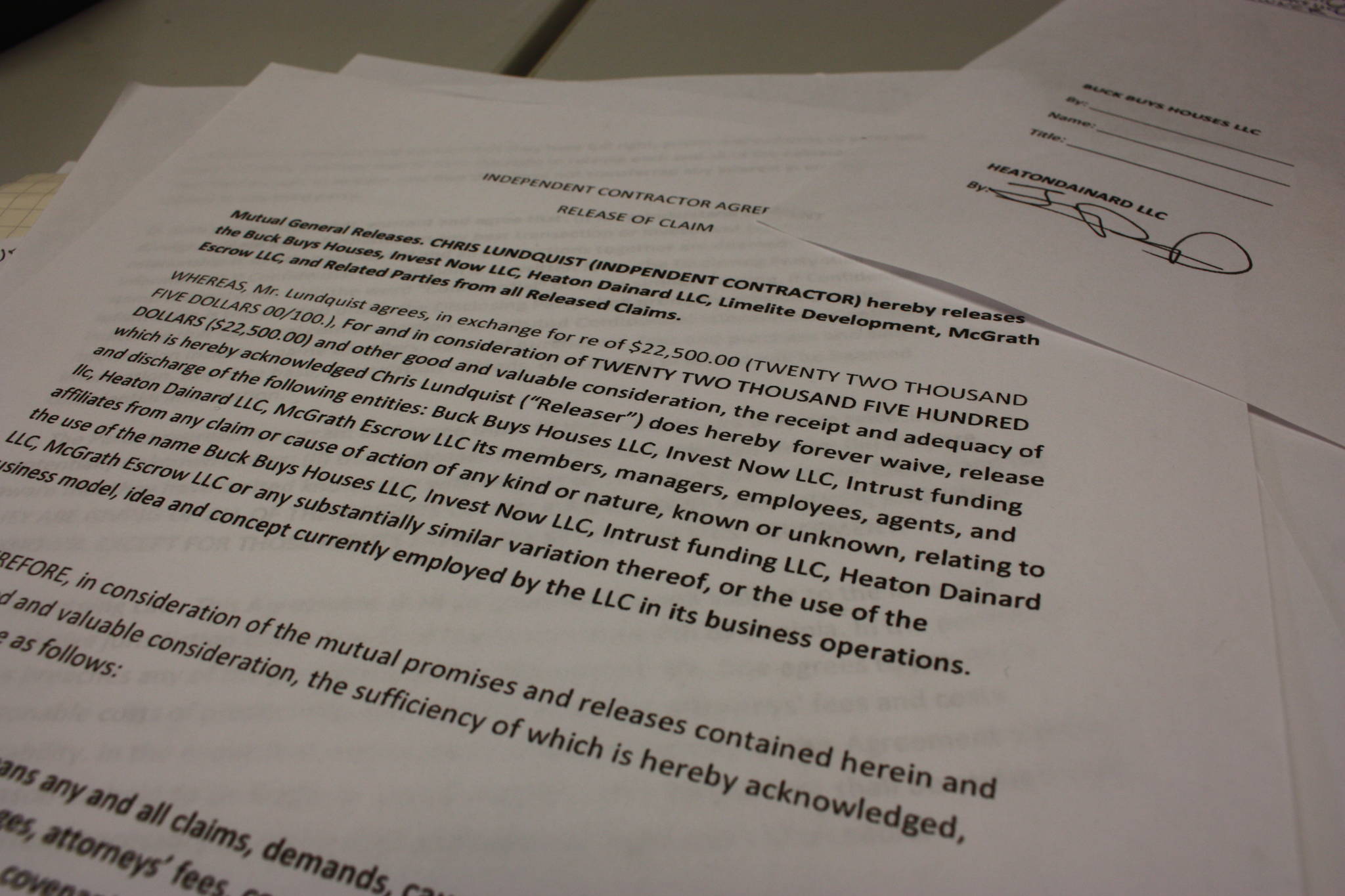

Dainard brought a release contract with terms that included a partial payout of $22,500 in home appliances, a “promise,” that Heaton and Dainard would make a “good faith effort” to remove, alter or change the 2013 Seattle Weekly article in exchange for a “release of claims” against Heaton-Dainard and their shell companies.

The contract was signed by Dainard on behalf of Heaton-Dainard LLC.

Lundquist said the terms of the contract were never really fully met because he did not receive the full amount of money that he was promised, nor did Heaton-Dainard make an effort to set the record straight in regards to what really happened.

In hindsight, Lundquist said he wished that Larson did not feel like he got taken advantage of, and wishes that he had chosen to speak with the Seattle Weekly reporter to give her the facts of the situation instead of ignoring her, which only protected James Dainard once the 2013 Seattle Weekly article was published.

He said Heaton was his friend and the one who introduced him to the real estate business. For years he never wanted to expose the truth of the incident for fear of being labeled a “snitch.”

According to him, it was not until Heaton told him to “stop playing a victim,” that he decided to go public with his predicament.

Lundquist said he plans to take legal action against the prominent real estate investors.

Neither principal of Heaton-Dainard Real Estate responded to request for comment.