The grainy footage shows two snarling pit bulls in a dimly lit barn, staring each other down through a haze of cigarette smoke. Walled in by a makeshift ring of three-foot-high plywood planks, the collarless dogs twitch and wag their tails, expending nervous energy like prizefighters shadowboxing in the ring in the moments before the opening bell.

Both dogs are males and have a tan coat and a white belly, which makes it difficult to tell them apart. They’re about 10 months old—young for fighters. This is their first taste of combat.

Each dog has a handler who grips it by the scruff of the neck and positions it opposite its foe in the corner of the 16-by-16-foot ring. When they’re released, the pit bulls collide with a dull thud. One dog lands on its back and the other pounces, grabbing hold with its jaws. The two animals spend the next several minutes growling and panting, locked in a ferocious struggle.

John Bacon, who owns the dog that’s on top, bends at the waist and rests his hands on the knees of his baggy overalls, hovering close to the tangle of fur and flesh. He cajoles his pit bull to release its bite and improve its position. The dogs tumble over one another and Bacon jumps out of the way. “There you go!” he shouts. “That’s where you want to be!”

The other dog is getting mauled. It emits a piercing squeal, followed by a whimper. Laughter ripples through the crowd. Joseph Addison, a spectator who wears his hair in a jumble of chin-length braids, suggests it’s time to stop the match.

“This motherfucker through, man,” he says to Bacon. “He’s done.”

Using a small, wedge-shaped piece of wood called a break stick, Bacon pries open his dog’s jaws, releasing its opponent. The animals are separated and taken back to their respective corners to “scratch.” If they charge again, the fight continues. If one dog refuses, it will be branded a “cur”—an almost certain death sentence.

At the moment of truth, the vanquished dog cowers while Bacon’s dog attacks without hesitation, biting down and thrashing its powerful neck in order to inflict maximum damage. Again the handlers separate the dogs. The fight is over.

Someone in the crowd asks the losing dog’s owners what they plan to do with it.

“I’ll take ‘im home,” one says.

“Take him home?” comes the incredulous reply. “Look at this shit! You’ll take him home?”

“Yeah,” the man repeats, declining the offer to use an impromptu electric chair: an extension cord rigged with alligator clips attached to one end. “I’ll take ‘im home.”

A year and a half later, Bacon describes the scrap in the East St. Louis barn as “just a little wrasslin’ match.” In dogfighting parlance, it’s known as a “roll”—a brief sparring session used to gauge whether a pup has the fighting spirit known simply as “game.”

“A contract fight is something you prepare for,” Bacon explains. “A roll is just 10, maybe 15 minutes. The dogs ain’t gettin’ hurt too much.”

He’s a carpenter by trade, but Bacon knows a lot about dogfighting. Still, there was one thing he didn’t know on March 22, 2009.

He was unaware that his dog’s opponent, Hammer, was the property of the United States government.

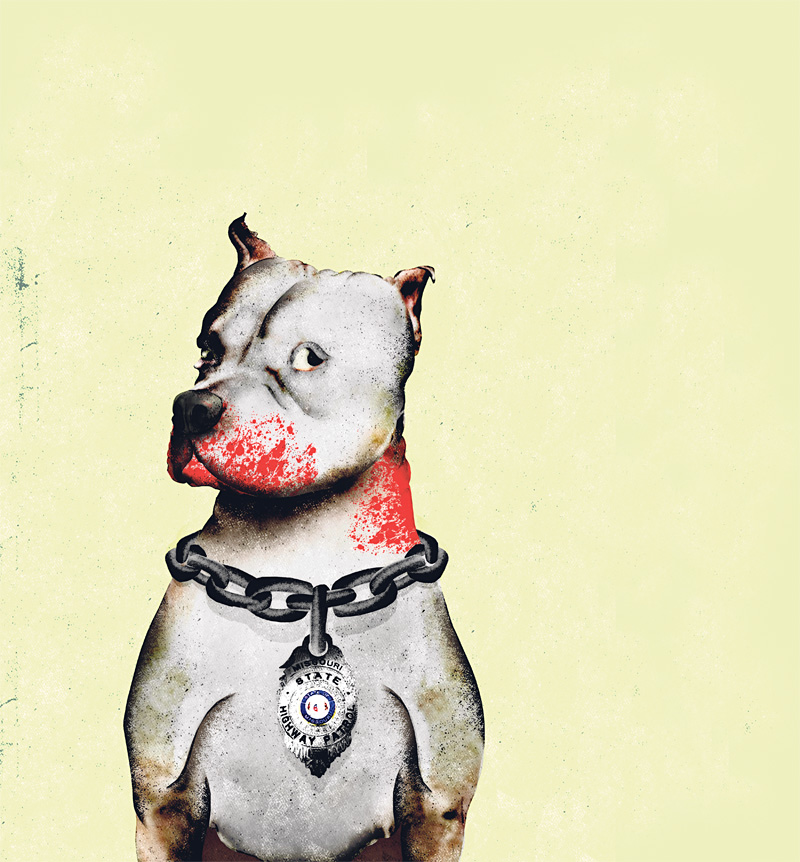

The dog was purchased, trained, and brought to the fight by Terry Mills and Jeff Heath, veteran Missouri State Highway Patrol officers who were conducting an extensive undercover investigation into the secretive and brutal world of organized pit bull fighting and breeding. Both men wore video- and audio-recording equipment concealed in their clothes.

Four months after the fight in the barn, a multi-agency task force conducted a series of raids in eight states. Agents arrested 26 dogfighters, including Bacon, and seized more than 500 pit bulls—the largest dogfighting bust in American history. In order to make their case, investigators had spent a year and a half taking part in the same gruesome activities for which they would later make the arrests.

In early 2008, Terry Mills was working on a domestic-terrorism task force headed by the FBI. The unit had received a tip that a “known domestic terror group” was standing guard at dogfights in rural Missouri.

Mills cultivated a source with ties to Bob Hackman, a renowned breeder of fighting pit bulls. The confidential informant worked as a “yard boy,” feeding and watering the dogs and “shaping” them for upcoming fights with a variety of training exercises.

Mills and an FBI agent outfitted their snitch with a wire and eavesdropped as he attended a series of dogfights in northeast Missouri. But after three months of sleuthing, they’d made no headway in the domestic-terrorism probe.

“The FBI said, ‘OK, we’re done. We’re pulling out completely,'” Mills recalls.

Where the FBI saw a dead end, Mills and fellow Missouri State Highway Patrol officer Jeff Heath sensed an opportunity.

The Michael Vick case had concluded less than a year earlier, when the former Atlanta Falcons quarterback pleaded guilty to a felony animal-fighting conspiracy charge and was sentenced to 23 months in federal prison. Vick’s high-profile indictment—complete with grisly descriptions of how he and his associates hanged, drowned, electrocuted, and shot several dogs—thrust dogfighting into the national consciousness. Congress passed a new law, the Animal Fighting Prohibition Enforcement Act, which took effect in May 2007 and made dogfighting a felony punishable by up to three years in prison.

Convicting dogfighters, however, requires that they first be apprehended.

The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) estimates that roughly 40,000 professional dogfighters are operating in the United States. The Humane Society of the United States says pit bulls and pit bull mixes make up a third of all dog intake at animal shelters nationwide; in some urban areas, the figure is as high as 70 percent. At the same time, the two nonprofits contend, law-enforcement agencies both local and federal are reluctant to devote resources to an offense that doesn’t affect humans and involves insular criminal networks that are difficult to infiltrate.

Infiltrating is precisely what Mills and Heath had in mind. But to gain access to any dogfighting ring, they knew they’d have to be active participants.

Terry Mills spent 16 years working undercover narcotics details. For two years in the late ’80s, he lived in rented apartments in western Missouri—”just going to bars and buying dope,” he says—as part of a prolonged probe of a biker gang called El Forasteros. Now a burly 55-year-old whose soft eyes and stubbled cheeks are set off by a bushy gray goatee, he proudly recounts how he started with virtually no knowledge of motorcycles and finished as a Harley devotee.

Jeff Heath, a stern-faced 46-year-old who sports a hoop earring and goatee and wears his brown hair pulled back into a shoulder-length ponytail, got his start with the St. Louis County Police Department and worked narcotics before joining the highway patrol. He was eventually assigned to the agency’s criminal investigations unit, where he partnered with Mills and the region’s Major Case Squad to solve murders across the state.

But both men knew next to nothing about the finer points of dogfighting.

“You saw Michael Vick on TV?” Heath asks rhetorically. “That’s about what we knew going in.”

Enter Tim Rickey and Kyle Held, animal-cruelty investigators with the Humane Society of Missouri. The pair had more than 10 years of combined experience breaking up animal-fighting operations. They helped school the detectives on rules and jargon—terms like “fanged,” which describes a dog’s incisors piercing its own lips during a fight.

The agents say passing themselves off as dogfighters to breeder Hackman proved to be the key to their initial success. They describe Hackman as a dogfighting “guru” who amassed a small fortune selling a highly regarded bloodline of fighting pit bulls known as Boyles out of his Shake Rattle and Roll kennel in the town of Foley, about 40 miles northwest of St. Louis.

“At one point [Hackman] told us he’d sold 70 puppies that year,” Mills says. “Those are going for at least a $1,000 a pop, and some of ’em were $1,500. They were the offspring of a champion. And everybody wants a champion dog.” Mills and Heath bought several.

Guided by their snitch, the investigators made the rounds to other prominent pit bull breeders in the state. In Missouri it’s illegal to own a fighting dog, which meant Mills and Heath could get a suspect to incriminate himself simply by expressing interest and asking him to demo a dog.

“He’d pull [a second] dog out of his kennel and get them together for a short period of time,” Mills explains. “It might be a minute, it might be two minutes. Then the case is made. He doesn’t have to say anything about money or entertainment. As soon as those two dogs are fighting, you’re done.”

The agents say they asked the breeders to include emaciated or injured dogs as “freebies” in the deals, which in some instances totaled $5,000.

“We’d tell him we were going to take it back to our kennel and try to nurse it back,” Heath says. “We would immediately turn it over to the Humane Society. It didn’t cost us anything, but the dog would have a much better life.”

Eventually the investigators were the proud owners of 40 full-grown, healthy fighting dogs, along with a dozen puppies.

They leased a parcel of remote farmland, and, after installing a mobile home on their spread and building a storage shed, purchased doghouses, chains, dogfighting gear, and pallets of pricey, high-protein dog food.

When it comes to housing, fighting pit bulls are afforded no luxuries. Their habitats are designed solely for the purposes of increasing strength, resilience, and aggressiveness toward other animals. Many breeders and keepers refer to their setups as “yards”—an apt description. The dogs are almost always kept outdoors. Heavy chains, chosen specifically to build neck and shoulder muscles, restrict their movements. The distances between the points where the animals are staked down are carefully measured so that they can come within a few feet of each other but never actually touch.

“They crave human contact so much,” Mills says. “They would go the length of their chain and turn around so their tail is facing you, just so you’ll brush it when you go by. They just love to be petted and touched.”

The detectives had to train their dogs to fight. To keep them lean and to maintain their weight class (dogs are matched against one another according to exact weight and gender), they put the animals on a diet that consisted of noodles and ground beef in the weeks leading up to a match. On the chain, the pit bulls would play tug-of-war with a length of fire hose, an exercise called “shake shake” designed to strengthen their jaws and neck muscles and, as Heath puts it, to “increase their sense of win.”

“We couldn’t really expose dogs and not have them at least be in shape,” Mills says. “If you’re going to put on a front, you can’t be a laughingstock.”

Though the investigators began by arranging dogfights in Missouri and southern Illinois, by January 2009 they found themselves “hooked” for matches as far from home as Oklahoma and Texas. By their own tally, they eventually made more than 150 undercover contacts and attended 86 dogfights.

“We ended up being involved and going to fights way more than a real fighter would,” Mills says. “Most only did two or three a year, because it’s so intense in the training process.”

The agents quickly realized that the region’s dogfighters were a tight-knit group. Conducting raids and making arrests in distant locales and returning home to continue business as usual was out of the question.

“In Oklahoma, by the time we got done and back to our motel that night, everybody in Missouri knew if we won or lost,” Mills says. “They all knew. We couldn’t talk to anybody without somebody else knowing.”

The tradeoff was extraordinary, nearly unfettered access to a world that had formerly been inaccessible to law enforcement.

Heath and Mills were surprised to discover that the dogfighters they were mingling with came from all walks of life. Suspects ranged from a registered nurse to a convicted killer out on parole. There was a crack dealer in East St. Louis, a high-school football coach in Texas, a schoolteacher in Iowa, a firefighter in Oklahoma. The agents even encountered a veterinary technician who hooked up his dogs to IVs to rehydrate them after fights.

“They’re sociopaths,” says Tim Rickey, the former Humane Society of Missouri agent who took part in the probe. “That type of person that can live a fairly normal existence, portray themselves [as] a lover of the breed, and go to church—and then stand around and cheer at one of the most barbaric acts you’ll ever see. They spend months with a dog and smile before a fight and talk about how good they are. And then they execute them in a second when they don’t fight well.”

Troubled by the mortality rate of castoff dogs, the detectives began offering to take the losers rather than witness their execution.

“Most of the time, they wouldn’t even let you have the injured dog,” Mills says. “They did not want their bloodline getting out of the kennel. They [suspected] we’d nurse that dog back to health” and breed it.

They also had to get creative in order to avoid executing their own losing dogs on the spot. While their hidden cameras captured the scene in East St. Louis in March 2009, Mills was able to rebuff the offer to dispatch the dog they’d named Hammer.

“Nah,” Mills can be heard saying when the lethally rigged extension cord comes his way. “I like to get rid of mine at home.”

Though Hammer survived, investigators say Joseph Addison, the man who brought the electrical cord, killed one of his own dogs later that night.

“Addison stated that he did not have ‘chain space’ for a dog who lost,” reads an indictment filed that summer. “Addison attached an alligator clipped cable to the female dog’s lip and rear flank. [The owner of the barn] handed Addison the end of the extension cord. Addison electrocuted the dog.”

Occupying two-and-a-half square miles along the northeast border of East St. Louis, Illinois, the village of Washington Park is home to approximately 5,000 residents and no fewer than seven strip clubs. This past April the mayor of Washington Park was robbed and shot to death after stopping on one of the town’s two main drags to offer a pedestrian a ride.

It was dark by the time Mills, Heath, their informant, and two other dogfighters arrived there on the evening of November 15, 2008. The undercover officers steered their SUV to a rundown white clapboard house with a junk-strewn lawn on the outskirts of town. The fighting pit was in the backyard, surrounded by a group of about 40 people. Everyone paid $20 to William Berry, the show’s promoter, better known by his street name, Black.

One of the night’s main events was a $2,000 showdown between Black’s dog and a pit bull who’d been boarded at Mills’ and Heath’s kennel. The owner of the dog had intended to handle the animal himself, but had fallen ill and asked the agents’ snitch to stand in for him.

The fight was a grueling one that dragged on for more than two hours. Pit bulls in top condition are relentless, and in the frenzy of battle they’re impervious to virtually anything short of heatstroke. Heath and Mills tell of seeing dogs fight through broken legs.

“The only reason a pit bull will quit fighting is because it’s hot,” Mills says. “It’s not because of the pain. It’ll fight for you for love and loyalty. It won’t quit because it’s hurtin’.”

In addition to steroids, some owners inject their dogs with epinephrine or, foolishly, methamphetamine and cocaine to increase their fighting drive. The stimulants can kill fighting dogs; they die from kidney or heart failure, or heat exhaustion.

And yet, contrary to popular belief, pit bulls rarely fight to the death. Not only is it unnecessary—the dominant animal usually proves itself before fatal wounds are inflicted—it’s imprudent. If a dog is game and descended from a reputable bloodline, its offspring will be valuable commodities. The detectives say this often provided a convenient excuse to end fights before their dogs sustained serious injuries.

“We’d pull the plug at the cost of having to suck up our egos and go on,” Mills says. “Once that referee says ‘Release your dog’ and they make contact, the case is made. From then on, we’re looking for an excuse to end this fight. Like anything, we’re very competitive guys and we wanna win. But it wasn’t about that.”

“If our dog was out there getting hurt, we’d pick it up,” Heath adds. “We had some story: ‘That dog’s worth a lot to us for breeding purposes. He’s obviously winning the fight, but he’s more valuable for me to take him home.'”

But on this November night it was someone else’s dog—and someone else’s $2,000—on the line. Surrender wasn’t an option.

By all accounts the two dogs fought until neither had anything left to give. They were lying on the floor of the pit exhausted, their jaws still locked on each other’s bodies. Addison, the referee, remembers Heath and Mills trying to find a way out.

“They was asking to call it a draw, call it even,” he remembers. “For some reason they wouldn’t call it a draw. Whenever one goes that long—which is rare, I’ve never seen it—obviously both dogs are in great shape. Neither was giving an inch. Usually they say, ‘I’m going to lose my dog and you’ll lose yours—let’s stop it.'”

Instead of calling it quits, Black did something totally unexpected: He picked up his dying dog without a word and fled.

A posse quickly formed, bent on extracting the welsher’s $2,000.

The chase ended at a house six blocks away from the fight site, with Black inside and Mills, Heath, and their handler/informant in their SUV, along with several dogfighters.

They sent in their informant to negotiate a truce. Black invited the man into the house and escorted him to the basement, where his dog lay on a countertop, barely alive. Meanwhile the detectives were left on the front lawn to talk their angry associates into going home empty-handed—without blowing their cover. They succeeded.

At 6 a.m. on July 9, 2009, agents from the FBI, the USDA, the Missouri State Highway Patrol, the U.S. Marshals Service, and myriad local police departments raided 29 properties in eight states. They seized more than 200 firearms and arrested 26 people, charging them with more than 100 felonies in all.

Terry Mills and Jeff Heath watched the day’s events play out from the FBI’s mobile command center in St. Louis.

Headed by Tim Rickey, teams from the Humane Society and the ASPCA accompanied the law-enforcement officers as they served the search warrants. Altogether the crews collected 407 dogs in Missouri and Illinois and 100 more from properties in Texas, Oklahoma, Nebraska, Iowa, Mississippi, and Arkansas.

The rescuers had little to fear. Although fighting pit bulls are fiercely hostile toward other dogs, they are remarkably submissive to people. Handlers won’t tolerate being bitten, and typically kill dogs that are aggressive toward humans.

“I will say overall the health of most dogs was pretty good,” Rickey says. “They weren’t receiving the level of care of my dogs or other animals, but [the owners] take good care of them—up to the point they put them in the pit.”

The rescued dogs were transported to a makeshift shelter in a St. Louis warehouse. Twenty-one were pregnant and eventually gave birth to 153 puppies.

In previous major dogfighting busts (prior to the St. Louis case, the largest was a 2007 bust in Ohio that netted 64 dogs and nine indictments), nearly all the seized pit bulls were euthanized. Debbie Hill, vice president of operations at the Humane Society of Missouri, says her agency hoped to set a new standard.

“People have a hard time believing these dogs aren’t absolutely ruined for life, that they’ll always be animal- or people-aggressive,” Hill says. “That’s not true. If they’re treated differently, given different opportunities, we found a good number of them could adapt.”

One by one the dogs underwent extensive behavioral analysis. In one trial, the pit bulls were presented with lifelike stuffed-animal replicas of various dog breeds. Some reacted with indifference. Others revealed how vicious they had become.

In the end roughly half of the 500 pit bulls passed the tests and found new homes. The rest were put down.

To date, 17 of the 26 suspects arrested in the 2009 raids have pleaded guilty and are serving time in federal prison. Authorities netted an additional 34 convictions in state courts and 18 more at the federal level in the cases of dogfighters who were arrested or charged in the weeks following the July bust. Eighteen cases are pending in U.S. District courts.

Altogether the investigation targeted 107 suspects. Eleven of those escaped prosecution on misdemeanor charges of spectating at a dogfight because the probe extended beyond the statute of limitations. Two men were tried, convicted, and sentenced to lengthy prison terms on charges unrelated to dogfighting. One was deported.

Among those currently incarcerated are Bacon, sentenced to 16 months, and Addison, who got two years.

In an interview at his family’s home in Washington Park a few weeks after the sentencing, Bacon questions the lengths to which investigators were willing to go in order to put him and his cohorts behind bars.

“It’s like they broke the law to get what they wanted,” Bacon says. “They were actually in the box with blood on them, fighting dogs. They was in knee-deep. They’re no better than the ones who got convicted.”

Bacon says he took good care of his dogs, and provides a copy of a recent vet bill to prove it. (He paid the $118 tab in cash and used an alias.) He says dogfighting is viewed differently in his community, that the lives of animals are not valued the same as those of humans.

Mills says the dogs the investigators acquired for their kennel were eventually turned over to the Humane Society for adoption.

Richard Callahan, U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Missouri, whose office decided what the dogs could be subjected to, says there’s no hard-and-fast rule that determines when and if an undercover investigation should be halted.

“It’s always a balancing act and judgment call that you make, and that’s made as honestly as one can,” he says. “If you cut off an undercover investigation too soon, you foreclose on the possibility of discovery of a wider range of criminal activity. At some point if you wait too long, you’ve allowed something to go on that shouldn’t be allowed to go on. Somewhere in between you make your best judgment.”

Local attorney Albert Watkins, whose client Ricky Stringfellow received a yearlong sentence for his role in hosting fights and electrocuting Addison’s dog, maintains that Mills, Heath, and their bosses pushed the envelope too far.

“It’s one thing being an undercover officer selling narcotics as part of a sting,” Watkins contends. “It’s a whole other thing to be participating in the very crime for which others are being charged.”

The investigation has been almost universally applauded by animal-welfare organizations. “Hopefully it will be duplicated,” Rickey says of the landmark case. “We saved more than 400 animals and a countless number of their offspring from being born into a life of torment and torture. Even more impressive long-term is the message that we sent to dogfighters throughout the country. This case really shook the dogfighting community up. They realized law enforcement is serious about this and remain very nervous that they are being infiltrated.”

The sentencing precedent set during the court cases in southern Illinois (one of five circuit courts in which the dogfighting cases have been tried) might make dogfighters even more apprehensive.

In 2008, the year after Congress cracked down on dogfighting, another new federal law upped the maximum sentence for animal fighting to five years. Federal guidelines, however, still specify that only zero- to six-month sentences should accompany typical convictions.

Because the guidelines don’t take into account factors like the number of dogs involved or whether the defendant was deeply involved in dogfighting as promoter or breeder, Judge Michael Reagan of Southern Illinois District Court created a three-tiered system of “professionals,” “hobbyists,” and “streetfighters.” He decided that the pros—especially ones who kill, maim, or mistreat dogs outside the ring—deserve the most severe sentences. He also ruled that the men must seek permission from the court if they want to own dogs as pets after their release.

Addison’s two-year term was the harshest penalty the judge doled out. Stringfellow was deemed a hobbyist; his 12-month sentence is the most lenient among those of his seven co-defendants. Bacon is serving his 16-month stretch in federal prison in Mississippi, while William Berry—aka Black—is locked up for a year and a day.

Reagan also composed what amounts to a 22-page research paper on the history of dogfighting. The document includes 125 footnotes and touches on everything from the “immense” popularity of the activity among American policemen and firefighters in the early 1800s to the current dogfighting craze in Afghanistan, where fights in Kabul now “draw as many as 2,000 people” and “betting pots run as high as $10,000.”

All the defendants have appealed their sentences. Citing the pending appeals, Reagan declined to be interviewed for this story.

Another legacy of the investigation is a tool that may help prosecutors convict dogfighters in the future. The Humane Society of Missouri and the ASPCA collected DNA samples from every dog housed at the temporary shelter. Geneticists from the University of California–Davis catalogued the information to create the Canine Combined DNA Index System, or CODIS.

“We know all these networks buy and sell dogs in fairly small circles,” Rickey explains. “This will be an important tool. They can tie animals back to one or more convicted dogfighters and show they’re from the same bloodline.”

Eleven months after the raids and 32 years after he joined the force, Terry Mills retired from the Missouri State Highway Patrol. His partner, Jeff Heath, is currently assigned to the agency’s narcotics unit.

keegan.hamilton@riverfronttimes.com

Keegan Hamilton is a former editorial intern at Seattle Weekly and a current staff writer for Riverfront Times in St. Louis.