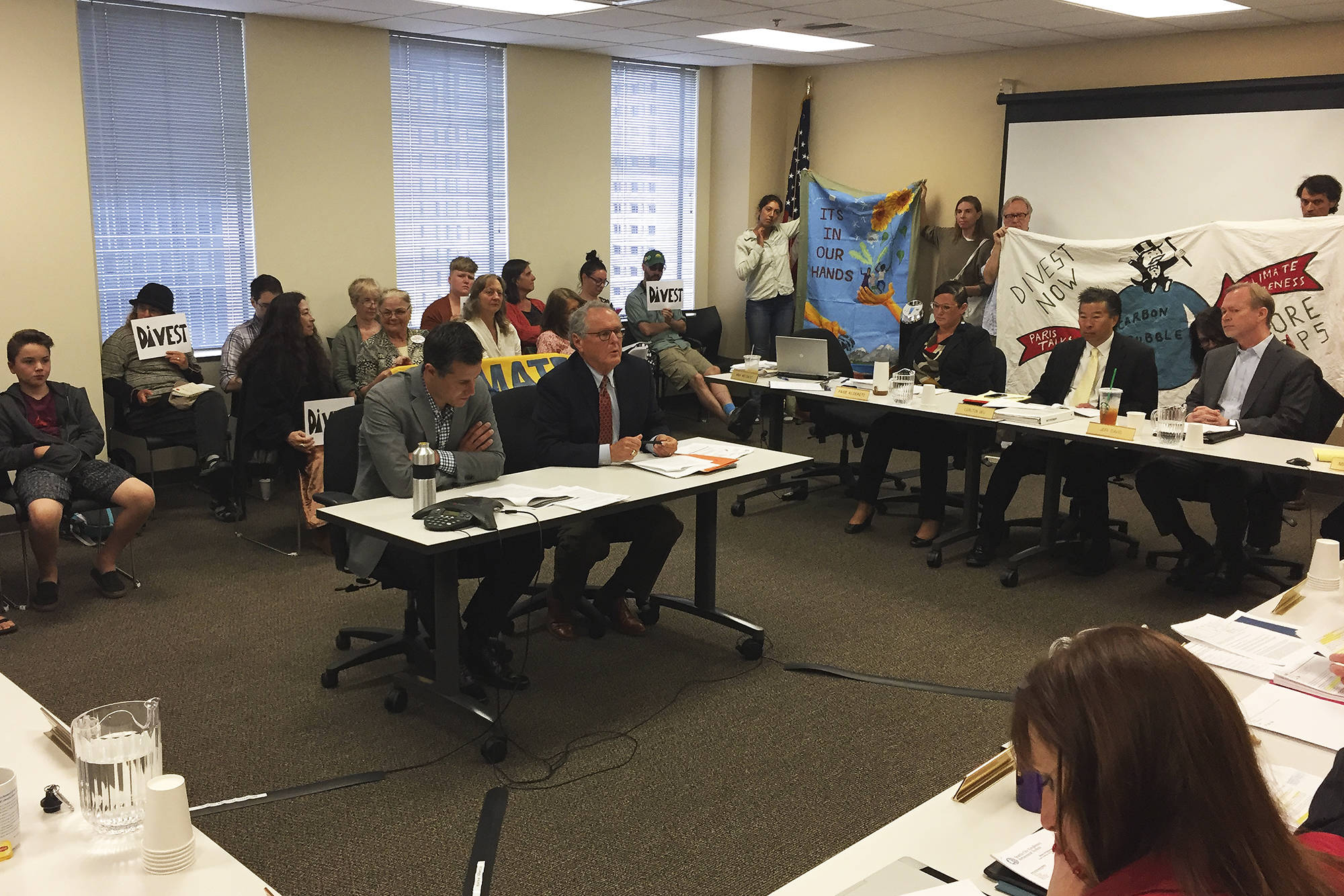

A fluorescent-lit room on the ninth floor of the Pacific Building downtown was packed for two straight hours Thursday morning with climate activists and divestment supporters. Following a ream of public comment—including from Councilmembers Mike O’Brien and Lisa Herbold and mayoral candidate Mike McGinn—financial and legal advisers repeatedly told the Seattle City Employees’ Retirement System (SCERS) Board exactly what they thought about divesting the city’s $2.5 billion pension fund from fossil fuels.

In short: Don’t even think about it.

“Our report reflects full engagement by all five members of the Investment Advisory Committee; it’s a consensus view,” said Steven Hill, an IAC member. His committee had been asked to review recent reports put together by the investment consulting firm NECP, then seconded by SCERS staff, that makes the case for why fossil fuel divestment would be risky, expensive, and unorthodox—and thus not be in the best financial interest of SCERS members.

“While we are concerned with the profoundly negative impact that climate change is having on our environment,” a SCERS staff memo reads, “divesting … would negatively affect expected investment performance, even if pursued on a limited scale (e.g. only coal) or if pursued over many years.”

“We agree with their conclusions,” Hill said, adding that the IAC did not see the need for further analysis, either. “We believe this is not a close call.”

Still, Hill conceded that one of the report’s arguments—that divestment has not been adopted by any U.S. public pension system—may not be true anymore. As the climate activists and groups that have been campaigning for months to get the city to divest its pension funds take care to point out, it has happened: Somerville, Mass., Cooperstown, N.Y., Washington, D.C., and the California state pension system have all begun to move at least some of their shares out of coal and oil and gas.

Activists had hoped that this national momentum—as well as an endorsement from Mayor Ed Murray and the poor performance of fossil fuel stocks in recent years—would persuade the SCERS board to vote Thursday to start divesting. Instead, the board took no action. But if they take the advice of Hill and others, they are very likely to vote no.

“It’s so frustrating,” said 350 Seattle’s Emily Johnston after the meeting. “It’s frustrating to hear smart, well-intentioned people continue to not get it.”

Many who spoke during public testimony invoked moral outrage—“Just think about your children and grandchildren,” one activist said, staring hard at the SCERS board members—and the environmental consequences of climate change. But they also pointed to financial analyses that make very strong economic arguments for divestment, too. A July 10 report by Gang Chen, former North American director of equity index trading at UBS Investment Bank, found that Seattle’s pension fund lost $100 million over the last decade by not divesting.

“Fossil fuels have consistently under performed the general market for over a decade now, and that has resulted in huge losses for the Seattle pension fund,” Chen said in a statement. “As the world continues to move away from fossil fuels, we can be pretty much sure that those losses will only continue.”

“To put it simply, fossil fuels are a bad bet,” McGinn told the room. (McGinn has been advocating that the city divest its pension funds for years now — at least since 2012, when he was mayor.) “Betting on oil companies today is like betting on Kodak film as digital cameras were being invented. It’s like betting on Blockbuster video stores as Internet streaming became a reality. Technology changes. The world changes.”

“Rather than timidity, what we need now is a little bravery,” added Andrea Faste, a city retiree. “I don’t understand how we can continue to ignore what seem to be significant losses.”

Yet that’s not at all how the city’s financial advisers see it. “We do not see the economic justification,” said Jason Malinowski, chief investment officer at SCERS. What’s more, he said, the city is not likely to find a consultant who would. “To our knowledge, there are no investment consultants to U.S. public pensions that have recommended that those public pensions divest from fossil fuel companies.” He also somewhat disagreed with Chen’s $100 million loss assessment, saying instead that SCERS had generated positive returns over the past decade that lagged behind the broader stock market.

The main arguments from Hill’s and Malinowski’s point of view are that 1) divesting creates too much risk and would cost the SCERS fund money, and 2) divesting won’t actually help in the fight against climate change.

“We are a very small shareholder in these companies,” Malinowski explained in response to a series of questions from Councilmember Tim Burgess, who chairs the SCERS Board. “If we were to sell our shares, there would be no impact on that share price. … Within milliseconds they’d be purchased by someone else.”

Instead, he said, it’s more effective to employ other strategies to push companies toward climate-friendly practices — notably through shareholder advocacy, wherein shareholders of a company can vote on resolutions that impel those companies to do things. That has been marginally successful so far, he said, pointing to SCERS’ indirect role in urging the asset management firm BlackRock Inc. to pressure companies to create climate-risk assessments.

Activists don’t see this as being very helpful.

Shareholder advocacy, Johnston and activist Alec Connon both argue, can only go so far. Shareholders can urge a company like ExxonMobil to treat its employees better, say, or to analyze its practices. But for shareholders to vote to transform the very foundation of Exxon’s business—extracting and burning fossil fuels—is not only unlikely, it’s illegal, Connon says. “You cannot put forward a resolution like, ‘Stop digging up fossil fuels.’” According to U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission rules, shareholders can’t fundamentally change the core business practices of a company.

Malinowski also missed the point on divestment, said activist Rebecca Deutsch. “If they moved those stocks today, yes, someone else would buy those stocks. That’s not the point. The point is if enough people divest, then it hits the bottom line, and it sends a big, broad message that this is unacceptable, and it gets other people involved to say this is unacceptable.”

What felt clear Thursday was that despite activists’ passion, the financial industry makes it hard to change things. Washington state law requires a pension board to act exclusively with regard to economic impacts. The board “cannot subordinate economic objectives to anything else,” said attorney Michael Monaco. Even if some members support divestment, such as the current employees and retirees who, Burgess said, have contacted the Board to say as much, that doesn’t matter: Every single member of the city’s pension system would need to agree. In Seattle, that means thousands of people.

The board did dicuss Thursday the idea of upping the portfolio’s investment in the renewable energy sector from 3 percent of its overall holdings to 5 percent, which represents a new investment of about $50 million. Still, no divestment vote was taken, as had been expected. It may be that board members saw what their financial advisers were recommending, and didn’t want to make that move in front of a hostile audience.

A discussion like this “is obviously not only about the money,” Johnston said, exasperated. “It’s about the money, plus business as usual. The money, plus what changes they’re comfortable making.”

sbernard@seattleweekly.com

Correction: A previous version of this story erroneously stated that the Board had voted against divesting and to increase the fund’s renewable energy investments from 3 to 5 percent. These ideas were discussed only, not voted on.