JUDY RIDGWAY is one of the few people left who thinks her husband isn’t responsible for the 49 Green River murders. Judy, 57, and Gary Ridgway, who observed his third month and 53rd birthday in King County Jail last week, had what she calls a happy 17-year marriage. “He was the best thing that ever happened to me,” she said the other day.

But on Friday, Nov. 30, 2001, King County Sheriff Dave Reichert announced that authorities had arrested “the” Green River killer. Though Ridgway was charged with just four of the murders and has pleaded not guilty, the media onslaught that followed echoed that interpretation, suggesting the 20-year-old serial killings had been solved with the capture of an Auburn truck painter, a suspect since 1983. King County Prosecutor Norm Maleng continued the drumbeat, issuing a press release and 18 pages of court documents; he hinted that the death penalty was a near certainty if Ridgway is convicted.

More than 600 stories have been aired or published locally since the arrest, most reasserting the prosecutor’s claims. Investigator Bob Keppel’s 1995 book The Riverman, recounting the quirky tale of imprisoned serial killer Ted Bundy trying to solve the Green River murders, has been reissued with a police mug shot of Ridgway on the cover. He is labeled “one of America’s most elusive serial killers,” now “finally apprehended.”

“They’re going to blame him for the disappearance of Amelia Earhart before they’re done,” says one of Ridgway’s attorneys, Anthony Savage, referring to the ongoing review of the 45 other Green River murders and more than 100 similar West Coast homicides being scanned for Ridgway connections.

But public perception doesn’t necessarily translate into a conviction. Just ask Ronald Goldman’s family.

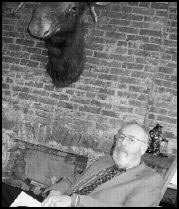

And Tony Savage, 71, the grand old man of Seattle criminal defense attorneys, plans to make his case and hopes to convince a jury that the Milquetoast-looking 5-foot-10, 155-pound, dyslexic Gary Ridgway, a homeowner often seen walking the family poodle, is not the force of evil behind the nation’s largest unsolved serial killings case.

“He’s not guilty,” Savage says. “That’s the defense. That’s where we start.”

There is a difference, of course, between innocent and not guilty. It’s the difference between “Did he do it?” vs. “Can they prove he did it?”

To date, Ridgway’s explanations and denials have been mostly unheard in the court of public opinion, from which comes the pool of jurors who will decide his fate. The prosecutor’s office has leveled its charges and outlined its case; Maleng says he will not comment further on the evidence. He has several months to decide if he’ll seek the death penalty and says he won’t use it to plea bargain with Ridgway, a Navy vet with a grown son from a previous marriage.

Ridgway’s defenders are undaunted. Savage and a tiny band of associates have begun reinterviewing witnesses, retesting evidence, and reviewing perhaps a million pages of findings and statements contained on stacks of CDs in preparation for a trial that may begin in 2004 and cost more than $15 million.

Through interviews with Savage and others, we outline aspects of that planned defense.

Preponderance of Evidence, meet Reasonable Doubt.

THE 1982-84 Green River killings were so named because the first victims were discovered in or near the river, starting with Wendy Lee Coffield, 16, on July 15, 1982. The 49 victims are connected by their ages (young), sex (female), lifestyle (some runaways but mostly prostitutes who often worked the SeaTac stroll), and manner of death (strangulation, in the cases where cause could be determined).

Their remains were found at seven remote multibody disposal sites. The bodies of seven presumed victims have not been found, and only five were found all or mostly intact. Four of those, Carol Christensen, 21; Opal Mills, 16; Marcia Chapman, 31; and Cynthia Hinds, 17, are attributed to Ridgway.

Prosecutor Maleng says he can show that Gary Ridgway was not working at the times the four women were last seen or killed. But when, exactly, were they killed?

The evidence he has so far reviewed, says Savage, indicates that “they haven’t the faintest idea when these girls died. They can put some within a day or so. In some cases they just don’t know.” An attorney working with Savage, Michele Shaw, says Ridgway was working overtime on some of the dates in question. “The overtime [shows] up on his paychecks,” she says, and provides at least partial alibis.

The defense is likely to also explore whether all of the women in Ridgway’s case were Green River victims. Christensen was discovered in Maple Valley, unlike the other three. She was also uniquely posed by her killer: fully clothed, a bottle of Lambrusco wine balanced on her stomach, two trout laid across her chest, a small mound of sausages in one hand. But since the tavern worker had been strangled with a ligature, as were many Green River victims, she eventually was added to the gruesome list.

“I mean, this Green River business,” says Savage. “Any dead body out there is a Green River victim, including bodies that haven’t been found.”

Then there’s the question of motive. Ridgway has maintained his innocence for two decades yet openly admits he was hooked on sex. Two ex-spouses and some former girlfriends and prostitutes claim he liked to have sex outdoors (one former girlfriend said they sometimes had sex thrice daily), and a few of these “camping and hiking” trips took place near some of the death scenes.

In two alleged instances, Ridgway showed violence toward women about 20 years ago. One ex-wife and a prostitute both say he put them in choke holds, though he wasn’t charged with a crime in either instance (his only prior arrests were for soliciting prostitution).

The ex-wives and others claim Ridgway liked kinky sex, went through a fanatical religious period, was verbally abused by his mother, and made derogatory remarks about his former spouses, suggesting he had motives to kill women.

Ridgway concedes he has a sexual addiction. But he insists to his attorneys that he was never abused by either of his parents. And the defense may well ask how many divorces are happy ones (one ex-wife admits to cheating during their marriage and Ridgway claims she gave him genital warts). In a recent conversation with attorneys, his current wife, Judy, was reportedly supportive of her husband, speaking in a loving way, reminiscing about camping trips, weekends together, shopping, gardening, and spending time with their respective extended families. She chats with her captive husband at least once a week. On the advice of attorneys, she wouldn’t comment directly for this article.

Some of the frank and consistent statements Ridgway gave could be exculpatory. For example, his admitted “fixation” with prostitution could help explain his regular presence at strolls (for sex, not murder).

News reports to the contrary, Ridgway never approached detectives offering information on the case (according to chief Green River Task Force investigator Tom Jensen, who has been cautious about claiming Ridgway is “the” killer). Ridgway always shied from the media spotlight, say his attorneys. He readily agreed to a polygraph test in 1984 and passed. (The county afterward claimed its test was flawed, and he agreed to a second test in 1987 with FBI agents; he later turned it down on the advice of an attorney.)

DNA WAS THE catalyst for Ridgway’s arrest. Now his attorneys want to use it in his defense. The question is: When Ridgway gave a saliva sample to detectives for blood-typing, did he give permission for it to be tested 14 years later by a technology he’d never heard of?

Last September, three of the Green River victims were allegedly matched to Ridgway using a new DNA lab procedure called short tandem repeats (STR). STR, which arrived on the scene in 1996 (but not until 1999 in Washington), enables forensic scientists to detect genetic traces on once-unlikely surfaces such as jewelry or a beer can in addition to traditional DNA sources such as hair and skin.

Earlier standard analysis turned up nothing of value from a saliva sample Ridgway had provided in 1987, following service of a search warrant on his home and vehicles.

Apparently at a detective’s request, Ridgway compressed a piece of gauze between his teeth to create the sample. He may have been told it would be used to determine his blood type, an earlier method of matching or eliminating suspects biologically.

But if DNA sequencing was mostly science fiction back then (first used in a court case in 1985, its broad application began only five years ago), did Ridgway freely approve such testing—then, or in the future?

If he did not give—or could not have given—such permission, could all the DNA findings be suppressed and never shown to a jury? That could cripple the prosecution.

It is a citizen’s right to refuse such a test. A Seattle defense attorney not associated with Ridgway’s case says of the blood- sample question: “That would be one of the first issues I would raise. That’s the case, isn’t it?”

But Paul Giannelli, a lecturer and professor at Case Western Reserve law school in Cleveland and a top expert on DNA law, says if detectives told Ridgway they were going to do a serological analysis, that’s sufficient warning to permit DNA testing.

“The U.S. Supreme Court uses a totality of circumstances test, which comes down to: Did they coerce him?” Giannelli says. “Unless he was affirmatively misled, I think the courts will admit” the DNA evidence.

Before any DNA is admitted, however, chain-of-custody questions must also be resolved. The defense wants to know how Ridgway’s DNA was collected, transferred, and stored, especially since it was gathered when DNA procedures were mostly unknown.

As with any evidence, it has to remain untainted to be admitted in court. The preservation chain is instrumental as well. O. J. Simpson is a free man today in part because his attorneys bedazzled the jury without really proving the samples were carelessly handled; even the implication of error was persuasive.

But if this evidence is allowed, how convincing is it?

DNA isn’t 100 percent foolproof, though investigators feel the improved STR procedure convincingly ties Ridgway to the two-decades-old semen found in the body of Carol Christensen, discovered in May 1983. Maleng alleges that a sperm swab from Christensen’s body matches Ridgway’s DNA to the extent that almost no one else on earth could be the issuer.

Similar but less persuasive DNA profiles allegedly tie Ridgway’s sperm to the bodies of Opal Mills and Marcia Chapman. Circumstantial evidence links Ridgway to the murder of Cynthia Hinds. These three were the third, fourth, and fifth Green River victims, all found Aug. 15, 1982, in the river and nearby on a the bank. Hinds, like Chapman, had a small rock inserted into her vagina, prosecutors say, and both bodies were found close together, weighted by rocks.

To convict Ridgway of Hinds’ death, a jury would most likely have to be convinced he killed Chapman. That, too, may depend on whether they first believe he killed Mills and, most importantly, Christensen.

Savage says scientifically he has only “a Reader’s Digest knowledge of DNA,” which is why he’s leaving that area to others on his team. But, he argues, “If it’s his DNA, that proves he was a customer for [some of] these ladies. It doesn’t show he killed them,” nor does it alone put him at the crime scenes. “We don’t know how many customers they may have had after Ridgway and who may have [apparently unlike Ridgway] used condoms.”

There’s scant other evidence placing Ridgway at the crime scenes. Authorities say some similar traces of fibers and common metals have been linked to Ridgway and the death scenes, but they are far from conclusive. His current and earlier residences and vehicles in the South King County area have been searched inch by inch at least four times, along with his work locker at Kenworth Truck in Renton and his safe-deposit box.

The most recent search found “no smoking gun,” in the words of sheriff spokesperson John Urquhart. Though lab tests continue, authorities have not announced the discovery of what would be the most compelling DNA link: evidence that any Green River victims were in Ridgway’s trucks or homes or disposed of on his property. The women were almost universally missing their jewelry, but none has turned up in Ridgway’s possession.

By itself, the old evidence was never enough to make a case. And “if all they’ve got [that is new] is DNA,” maintains Savage, “they’ve got substantial problems.”

IF NOT GARY Leon Ridgway, then who?

Over the years, authorities have collected the names of 20,000 potential killers, some called serious “persons of interest.” Many are still being investigated in connection with the 45 remaining deaths.

Sheriff Reichert and investigator/ author Bob Keppel prefer the term “the” Green River killer; Keppel says he’s convinced Ridgway will be proven to be the killer portrayed on his book cover. But the apparent consensus is that at least two, and as many as four, killers may have had a hand in the serial murders (some perhaps as helpers or copycats). In two of the deaths Ridgway is charged with, in fact, a witness reported seeing two men in a pickup driving away from the crime scene.

To prove Ridgway is a serial killer of the four women, the prosecution may have to demonstrate that the victims were among 49 women slain. That would open a big door: Were these in fact serial killings, and if so, by how many killers?

At issue could be such basic questions as why, if the killings began in 1982, did they stop after 1984? Law enforcement profiles generally maintain that a serial killer may pause but never retires. In the past, officials had several answers for this question, such as the killer moved away or died. Ridgway did neither. Prosecutors may cite some rare examples of serial killers who stopped abruptly, as well as argue that with all the unsolved out-of-town cases, who’s to say the killings really stopped?

Given that there are reams of reports and 10,000 pieces of evidence stored in a South Seattle warehouse, there’s no telling to what extent the defense can explore the “other man” theory and cast doubt that the real killer of the four women has been winnowed out of thousands.

After all, authorities thought they had the Green River killer years ago. In fact, three other suspects have been named in the past. Some of their homes were searched, too. None was charged. As part of the defense strategy, it wouldn’t be surprising to see the names of some of them on Ridgway’s witness list.

Who knows how dramatically the suspect list might change by 2003? Just this week, British Columbia pig-farm owner Robert Pickton was charged with two of 50 suspected murders of Vancouver prostitutes that Ridgway has been linked to. Does this, conversely, make Pickton a suspect in the Green River case?

Ultimately, Tony Savage says, he intends to demonstrate what he professes to believe about his client. “Lord knows I’ve been fooled before,” says the man who has defended a legendary legion of accused killers. “But sit down with this guy in a tavern, talk with him for a half-hour, and if I come up to you and say, ‘That’s the Green River monster,’ you would say, ‘No way.'”