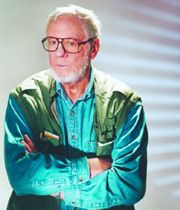

Jack Olsen is a big man; lanky, but a little stooped now. He looks all of his 75 years, his face deeply scored with the wear and tear of a life of spent hanging out with murderous sociopaths, being the father of eight, and drinking with reporters. His age is belied by the intensity he generates in conversation. He has, it seems, read and done everything there is to read and do, and has opinions on all of it. He’s not a know-it-all—he just has an intense need to engage. And he’s very engaging, indeed; topics of conversation can range from Mariners pitchers to literary criticism in America to James Joyce.

Last Man Standing: The Tragedy and Triumph of Geronimo Pratt

by Jack Olsen (Doubleday, $27.50)

Olsen’s booming voice spills out in perfect sentences and features the huge vocabulary and literary allusions that come from a classic liberal education, a voracious curiosity, and, of course, the mileage of being a journalist for 50 years. He’s covered the integration of Little Rock’s Central High School, been deputy sheriff in a Colorado town, and been cursed by Gypsies. He played touch football with the Kennedys on Sundays in Hyannisport until he wrote about Ted’s bad night in The Bridge at Chappaquiddick. For all Olsen’s rants, there’s an anachronistic graciousness about him. For all his loquaciousness, he rejects the literary scene for trolling in his 17-foot open boat around Skunk Buoy, a salmon hole two miles off LaPush.

As a writer, Olsen has a finely tuned ear for the language of time and place. A former Time magazine bureau chief and Sports Illustrated editor, the Bainbridge Islander has authored over 30 books—six of which are novels. He’s mostly known for his reporting, having been a journalist for 50 years. His books, covering a wide range of subjects, include The Night of the Grizzlies, an eco-thriller, and Silence on Monte Sole, a detailed study of a Nazi massacre in Italy.

Olsen’s best-known works, though, fall under the heading of crime journalism. Like Son: A Psychopath and His Victims, the story of Kevin Coe, Spokane’s South Hill rapist whose rich and influential mother was sent to prison after trying to hire a hit man to kill the judge and prosecutor who convicted her son. Doc: The Rape of the Town of Lovell is an incredible account of a rural Wyoming doctor who relied on his patients’ naivete and Mormon female submissiveness to rape generations of women on his examining table. Both Son and Doc earned Olsen the prestigious Edgar Award from the Mystery Writers of America.

“I’ve always been fascinated with how seven or eight pounds of protoplasm can go from his mommy’s arms to become a serial rapist or serial killer,” Olsen notes. “This is my compulsion.” He raises his voice and emphasizes his point by bringing his size 11 foot to the floor. “A crime book that doesn’t do this is pornography.”

Olsen differentiates his work from “true crime” writing, most of which he says now typifies the decline of nonfiction. He says it’s about accuracy in reporting. The problem presented itself in the inventive conjecture and made-up quotes in Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, the extravagantly successful “nonfiction novel” about the 1957 Clutter family murders that is considered the first true-crime book.

Olsen fast-forwards 30 years to the success of the “nonfiction” book Sleepers by Lorenzo Carcaterra. “Here was an $9 million book: a story of injustice in Hell’s Kitchen,” he says, gesturing with his huge hands. “Very sensational—a priest suborning perjury, the DA putting in the fix, two heroic boys getting even for a year in a reformatory where they were sodomized. It was 100 percent bullshit.”

Olsen and six other nonfiction writers unsuccessfully petitioned the publisher, Ballantine, to withdraw the book, refund the money of those who bought it under its pretense of nonfiction, and reissue it as a novel.

“I’ve reached the point,” Olsen says darkly, “where if my next door neighbor turned out to be the goddamndest quadruple murderer involving sex, incest, serial murder, I wouldn’t write about it. It would go right on the true-crime shelf, in between this piece of crap and that piece of crap and the average reader would say, ‘There are three pieces of crap.'”

Press and television, as The New York Times’ Max Frankel observes, “are in a heroic battle to preserve the meaning of fact and the sanctity of quotation marks. Reporters have been losing their jobs for committing fiction, a crime that is no crime at all in too many other media.”

Olsen agrees. “Other forms of journalism insist on things being true, but the one form that’ll be around a hundred years from now—books—nobody cares. With computers, this should be the heyday of truth and accuracy in journalism. I’ve suggested book publishers have fact-checking departments like newspapers, but they say it’s too expensive, that books cost too much already.”

Olsen’s new book is about justice in America; the story of how the slow-grinding process finally and miraculously redressed a long-standing wrong. Elmer G. Pratt was a good boy: friendly, courteous, and kind. Known as “Geronimo,” he did well in high school, stayed out of trouble. He helped support his large family after his father was incapacitated by strokes. Pratt joined the Army, toured Vietnam twice, made 64 combat jumps, got wounded and decorated for bravery, and returned a hero to his home in the black “across the tracks” neighborhood of Morgan City, Louisiana.

He stayed away from politics until the elders of his black community advised him to become aware of the civil rights struggle that was erupting across the country. In 1968, on their counsel, he went to Los Angeles and joined the Black Panther Party. Eventually he became Minister of Defense, head of the LA chapter, and found himself in a tense environment of relentless police harassment.

Los Angelenos, agog at the spectacle of Watts burning and ghettos exploding all over the country, felt threatened by these big-haired, rifle-toting, confrontational black revolutionaries and didn’t much care about their ghetto social programs—they just wanted them gone. And they didn’t care how the police did it.

Years later, it came to light that Panthers were targeted by a systematic FBI and police counterintelligence program. J. Edgar Hoover, reviewing Pratt’s file, gave the order: “Neutralize him.” In 1970, Pratt was amazed to find himself arrested for the brutal attack of a couple on a Santa Monica tennis court that resulted in the woman’s murder.

Jack Olsen spent three years studying 55,000 pages of documents, doing hundreds of interviews, and chronicling a case that shouldn’t have gone to court but ended in Pratt’s wrongful conviction. Eyewitnesses changed descriptions of the assailants over time; police failed to follow up on leads on other suspects. The state’s main witness, fellow Panther Julius Butler, hated Pratt for personal reasons and was a police/FBI informant—facts the prosecution kept from the jury. The defense team (including a scrappy pre- O.J. Johnnie Cochran) didn’t know until years later that the FBI had tapped their phones and planted moles in their office who attended defense strategy sessions.

Pratt served 27 years of a life sentence at San Quentin. Luckily, he was convicted during a brief period in California when the death penalty had been struck down. “A year earlier or a year later,” says Olsen, “he’d be in the grave.” (Other convicts spared at that time include Charlie Manson and Bobby Kennedy’s assassin, Sirhan Sirhan).

Pratt spent his first eight years of prison in solitary confinement. He was routinely beaten by guards and set up for attacks. Never broken, he educated himself and instituted prison social programs and reforms.

“It’s astounding to me,” says Olsen. “Hundreds of people over the years— police, prosecutors, judges, FBI officials, attorneys—knew Geronimo was framed and did nothing.”

The story has plenty of heroes: Stuart Hanlon, a young, rich, Jewish law student from New York, came to Pratt’s aid and stayed on the case for nearly 20 years. He ceaselessly tried to get him released with the help of Rev. James McCloskey, whose Christian prison ministry focuses on the wrongfully imprisoned. They were able to entice Cochran back on the case, and after many appeals and court appearances, the conviction was overturned. Pratt was released in 1997. In April of this year, he settled his lawsuit against the LAPD and the FBI out of court for $4.5 million.

Pratt’s astounding story is written by Olsen in a style that, though the outcome is known from the beginning, keeps the reader turning all 500 pages in suspense. How could Pratt survive the horrors of prison? How can people so blatantly ignore such an injustice? Would any judge listen to new evidence? Would Pratt’s siblings, mother, or friends crack under the ordeal?

The out-of-pocket cost of researching Last Man Standing, with the travel and other expenses, was a typical $50,000, another reason writers are deserting nonfiction. “The best authors can’t afford to spend a couple of years getting it right when there’s no premium for it,” Olsen says, rattling the coffee table. “We could just as easily sit home and make it up.”

Olsen is praised nationally not only as an author but also as an expert of criminal pathology. His only problems with critics, surprisingly, have been in Seattle. For years, his books were trounced by the Times and treated by the PI as if they didn’t exist—resulting in a poor readership base in his hometown. His feud with former Times books editor Donn Fry goes back to a 1991 review of his book, Predator, the story of the wrongful conviction of Steve Titus, who served years of prison time for rapes he didn’t commit, and Paul Henderson, the Times reporter who won a Pulitzer Prize investigating the case and cleared Titus. Charles Salzberg, in The New York Times, wrote a thoughtful piece about Predator, calling it “a meticulously documented case history” and lauding Olsen’s “effortless style.”

But under the headline “Author’s Pulp Treatment Trivializes Sensational Story,” a condescendingly written review by Clark Humphrey contained so many factual errors that Olsen threatened to bring a libel suit. The Times was forced to print an apology, a retraction, and a scathing letter by Olsen.

Thus began a series of bad reviews (Olsen calls them “muggings”) by the Times, several with errors that ended with published apologies and corrections.

Why would the Times carry on this vendetta as Olsen claims? Originally, he says, it was for some criticisms of the Gray Lady in Predator. This may be hard to prove, but it’s undeniable that the Times reviews were remarkably different than others. Seattle Weekly’s former books editor Bruce Barcott said, “No paper in the country treats Olsen’s books as . . . well, strangely as the Times.“

Happily, Last Man Standing was warmly received recently in a syndicated review in the Times and Olsen’s last two books have received attention from the P-I as well. Olsen says, “Publishing a book may be described in the vulgar words of one of my colleagues: ‘You drape your balls across the anvil and hand everybody a hammer.’ And when they take a good whack, it’s bad form to scream.”

Olsen broke all the rules and screamed when they whacked him. He readily admits, “It was not the circumspect thing, nor the commercial thing to do, and it had a major effect on my career. But I’d do it again in a minute.”

Jack Olsen appears October 22 at Northwest Bookfest.