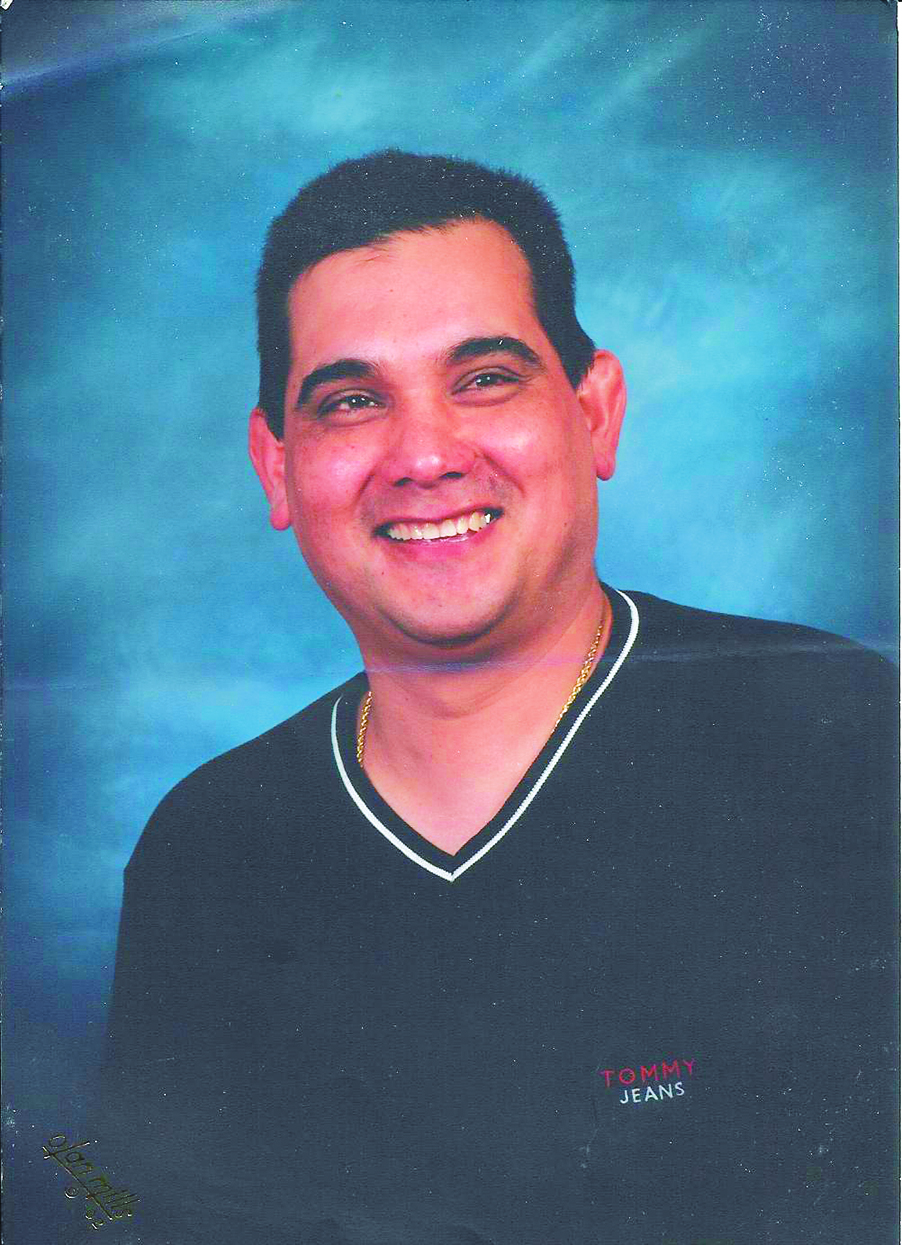

City Councilmember Tim Burgess addresses Prop 1B after the measures resounding victory. Photo by Kyu Han

As early as 11 a.m. yesterday, the campaign for Seattle’s Proposition 1A—one of two dueling preschool measures on the ballot—declared that the vote would likely be too close to be call. “We do not think there will be a clear result tonight,” read the statement by the union-backed campaign.

Oh, how wrong it was. By a margin of 65 to 35 percent, voters overwhelmingly cast their support for a subsidized preschool program, according to last night’s preliminary tally (which is estimated to account for almost two-third of the total vote). More strikingly, voters decisively chose city-backed Proposition 1B over the union plan. Prop 1B won 67 percent of the votes counted, while 1A garnered just 33 percent.

Prop 1A still wasn’t conceding. “We look forward to seeing the next batch of ballot returns,” SEIU 925 President Karen Hart said in a statement, the campaign’s only comment of the evening. Hart’s union and the American Federation of Teachers of Washington were the two unions behind the measure.

Her remarks seemed a strange denial of the obvious. As City Concilmember and leading Prop 1B supporter Tim Burgess observed, “It would be almost impossible” for the 1A campaign to overcome a margin that big. During a campaign party at Capitol Hill’s Sole Repair last night, Burgess jubilantly called the outcome “stunning.”

The vote defied conventional wisdom, which held that voter confusion over the two competing measures would spell defeat for both. And there’s no doubt about it; the two propositions added up to perhaps the messiest, most confusing choice ever presented to voters in this city. It was hard to keep straight which similarly-named proposition was which, the details of both plans were complex and the relevant ballot questions seemed illogical (even if you voted against enacting any preschool plan, you were still asked to choose between 1A and 1B).

Burgess gave voters credit for sorting out the mess, and perhaps he’s right. A margin that lopsided indicates that they were making a clear choice. In doing so, they rejected some extremely negative spin from the 1A campaign, which hammered away at the idea that the city’s preschool plan was, as one ad put it, “bankrolled by wealthy Republican donors and for-profit charter school supporters.”

Campaign spokesperson Heather Weiner told Seattle Weekly that 1A’s backers were merely responding to attacks leveled by the competing campaign. But those attacks, which centered on the lack of funding laid out in 1A’s plan, had a more measured tone.

It’s a shame that 1A went that route, really, because the measure did have some things going for it—the biggest of which was its intention to provide a broad system of affordable childcare. The city’s plan, in contrast, is a more limited pilot program serving only three- and four-year olds in designated preschool classrooms. Unlike 1A, though, the city’s plan is one that comes with funding, in the form of a $58 million property tax levy. That essential practicality won 1B numerous endorsements from the media and an array of civic leaders.

Education blogger Melissa Westbrook points out that there are still a lot of unanswered questions about 1B. Among them, where exactly are the city’s new preschools to be located and who will get to attend them? She worries that Seattle Public Schools, which has been working with the city on its plan, will be “pressed for space they don’t have” and that slots in the new schools won’t necessarily go to the low-income kids who need them the most.

Burgess dismisses these concerns, saying the city is not relying on the school district for space and that it is targeting exactly those kids Westbrook is worried about. Yet he agrees that there are questions yet to be worked out. “The next step is to develop the implantation plan,” he says.

“One of the big issues we have to work on is how we handle it if we have more people applying than there is space,” he elaborates. There will be room for just about 300 preschool students in September; the program will grow to 2,000 students in four years. Boston, which has a subsidized preschool program, uses a lottery, but Burgess says he wants to avoid that. The city has a lot of work to do over the next few months to figure it all out.

nshapiro@seattleweekly.copm