In the days following 2001’s Nisqually earthquake, one of the images that kept flashing across CNN was of fallen bricks on the streets and parked cars of Pioneer Square. One of the oft-repeated video sweeps showed the facade of the Fenix Underground nightclub, its old red brick slashed away, the club in near ruins. The Fenix closed its location at Second Avenue and Jackson Street and moved to a new location on First Avenue South which, damaged itself, underwent expensive renovations and reopened in 2003.

Three weeks ago, the Fenix closed again, quietly, this time the victim of financial distress.

This week, another Pioneer Square club veteran is leaving the nightlife business. Steve Crosier, the longtime general manager of Doc Maynard’s, is quitting June 30.

“I’ve never seen business as bad as it is now,” he says. “We’re doing maybe one-third of what we used to do.”

Business is that tough, for some, in Pioneer Square. Galleries have closed or moved and Mitchelli’s, a landmark for 29 years, is for sale. Even the dining spot billed as the city’s oldest restaurant, Merchant’s Cafe at First Avenue South and Yesler Way (founded in 1892), has struggled. It’s currently closed and undergoing a makeover. Carolyn Staley Fine Japanese Prints recently moved from the neighborhood to Pike Place Market, and high rents pushed out legendary book dealer David Ishii, a First Avenue fixture.

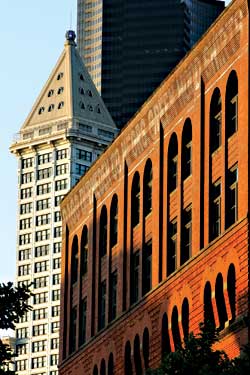

The hard times aren’t universal, but Pioneer Square is poised for more changes and challenges. The neighborhood is home to about 2,000 people—75 percent of whom live in homeless shelters or subsidized low-income housing, or sleep in doorways. The other 25 percent are Seattle’s downtown urban pioneers, more upscale folks who live in the condos, apartments, and lofts of the area’s restored old-world brick buildings.

They are about to get new neighbors. Lots of them. The city of Seattle is hatching plans to double the population of Seattle’s historic center. It won’t be moving 2,000 street people from elsewhere in the region and dumping them in Pioneer Square. Instead, development plans are on track for 2,000 new residents to live in about 1,000 new units of housing to be constructed in and around the Square in the next few years. Think of it as a smaller-scale version of the planned Denny Triangle redevelopment.

The housing won’t be cheap. The majority of the units are intended for the urban gentry who can afford $500,000 for 1,100 square feet and up to whatever it is you get for $1 million or more.

The change will be especially profound near the former Kingdome site, now the 500-car North Parking Lot. An official announcement was expected this week from King County that it would be redeveloped as an urban village with two towers, one as high as 24 stories, and about 800 residents.

Development always comes with a price. Million-dollar-condo buyers generally don’t mix well with the homeless and nightclub goers, preferring to re-create suburban mores in urban climes. And that’s the question hanging over all of this: Can Seattle improve Pioneer Square, revive its economy, keep its character intact, and retain the very urban funkiness that made it interesting in the first place without turning it into Green Lake?

Pioneer Square is literally where Seattle began, after the Denny party tired of windswept Alki and moved across Elliott Bay in 1852. As the city grew, it came to be crowded with shops, saloons, whorehouses, and industries on what was little more than landfill from the Duwamish River. No place else has more dramatically reflected Seattle’s boom and bust cycles. There was the great fire in 1889 that leveled much of Pioneer Square and spread north. Rebuilt in the 1890s, it was the jumping-off point for the Alaska and Yukon gold rushes, which kick started the city’s prosperity and growth. In the 1930s, Seattle’s Hooverville was located just southwest of the neighborhood.

Later, the Square became a blight zone after the city had developed north into downtown proper and the Denny Regrade. Many of Pioneer Square’s classic brick buildings were abandoned or turned into flophouses. In 1970, an arson fire at the Ozark Hotel in what’s now the Denny Triangle killed 20 longshoremen and forced city officials to require flophouse owners to bring their buildings up to code. As a result, old hotels closed (the State Hotel’s old sign still offers rooms for 75 cents a night) and remained vacant. The homeless took over the streets.

In the 1970s, the city declared Pioneer Square—from Columbia Street south to roughly Royal Brougham Way, bounded by Fourth Avenue and Alaskan Way South—a historic district. The idea was that the place would get cleaned of its blight, businesses would flourish, and a new generation of urban dwellers would arrive. In 1974, the Kingdome opened due south of the neighborhood, but Mariners and Seahawks fans never did much for the neighborhood aside from making business for sports bars like Sluggers and the Triangle Bar on First Avenue South.

“It was a curse,” says Art Skolnik, the first manager of the Pioneer Square National Historic District in the 1970s. “It didn’t provide anything that would help Pioneer Square.”

Eventually, Pioneer Square turned into a hodgepodge of cheap artists’ lofts, restaurants, eclectic shops, galleries, nightclubs, and homeless shelters. Nirvana and Soundgarden both played at the OK Hotel in the late ’80s and early ’90s. (According to legend, the OK Hotel is where “Smells Like Teen Spirit” was first performed live.) Pioneer Square was wild in those days, the place where nice Seattle didn’t go to party because it was filled with drunken kids from the burbs.

By the late ’90s, many of the old brick buildings were home to dot-com start-ups. Then came the dot-bust in 2000. The next year on Mardi Gras, a full-scale urban riot the Seattle police didn’t wade into left Christopher Kime stomped to death near the Pergola, and the very next day, the Nisqually quake hit, rendering many buildings uninhabitable until they were given seismic upgrades.

People hold different views about just how disastrous Mardi Gras and the quake were for Pioneer Square.

“That’s just the media,” says Tina Bueche, a longtime resident and business owner, of the many news stories that have sought to link the twin events to the decline of Pioneer Square in recent years.

Regardless, business in the area has remained dicey ever since, despite the earlier openings of Safeco and Qwest fields. Fans like to walk through the neighborhood to get to a game, but they don’t always come back, leaving the Square to its low-income and homeless residents and the music clubs to the suburban crowd.

Besides, Pioneer Square has a dangerous reputation among many in the Seattle area. There are typically a few shootings each year near the clubs, many fights (including one last year that left Seahawks cornerback Ken Hamlin in intensive care), drunken frat boys tossing Corona bottles through shop windows, and crack dealers, plus all the homeless people and panhandlers. In recent years, many people have stopped going to Pioneer Square, especially with the advent of club scenes in Belltown, Capitol Hill, Fremont, and Ballard.

One business, Crosier says, is flourishing through it all: the Underground Tour, run out of Doc Maynard’s. Its best year ever was 2005.

Soon enough, the real action is going to be above ground, as a result of the ongoing real-estate boom in Seattle. Anticipating this, in 2003, a collective of rich developers launched the so-called Seattle South Downtown Vision. Including developers Greg Smith and Frank Stagen, their plans foresaw some 12,000 new housing units jammed into developments stretching from the neighboring International District to the Port of Seattle’s Pier 46 (see “So Long, SoDo,” April 24, 2004).

The city is now trying to corral all of the development oomph in its “Livable South Downtown” plan. It’s in the early stages, what urban planners call the “visioning process.” City planners will send proposed building code changes to the City Council late this year or early in 2007.

Already, it’s clear that there will be none of the 40-story condo towers now allowed under recent code revisions in the Denny Triangle and downtown (see “Time to Grow Up,” Aug. 10), projects that are already well-advertised in Alaska Airlines’ in-flight magazine before ground has been broken in some cases.

In Pioneer Square, as well as the adjoining International District, the emphasis will be on building heights that don’t disrupt the historic scale of the neighborhoods. According to city documents, initial proposals will be for heights up to 125 feet in Pioneer Square, with higher buildings allowed adjacent to the neighborhood. On the North Parking Lot, city planners call for scaled heights—150 feet close to King Street and 240 feet (about 24 stories) just north of Qwest Field.

As lofty as that might seem amidst some of the area’s classic brick buildings, the neighborhood is home to the Smith Tower, at 522 feet, one of America’s great classic skyscrapers.

Already, Smith plans to develop a half-block site opposite Occidental Park at South Washington Street and Occidental Avenue South. The building may reach 12 stories and should have 150 housing units, says Smith. A 13-story building is already being built at Second Avenue and Yesler Way (it will co-house a new homeless shelter for the Chief Seattle Center). There are plans for Historic Seattle and developer Nitzi-Stagen to rework the Seattle Plumbing Building between First Avenue South and Occidental Avenue South into 69 condo units.

Smith is also floating plans to cap the railroad tracks along Fourth Avenue, connecting Pioneer Square with the International District and creating a huge office campus complete with a 35,000-square-foot pond.

“I think this may be the Square’s salvation,” says Crosier.

Bueche says none of this bothers her a bit, as long as the city finds “the balance” between upscale and working-class residents.

That will be tough to make happen, says Tim Ceis, the deputy mayor.

“I think our goals are 15 percent [of new units] will be affordable and workforce housing,” he says. Workforce housing is variously defined as being targeted for people making from about 80 percent to 120 percent of median income, roughly $40,000 to $60,000 a year.

The remaining 85 percent would be market-rate units. “Most of it is going to be market rate, and I think that’s what the Square needs. I can’t say it equals gentrification. It will create a healthy balance,” Ceis says, referring to a neighborhood demographic that is heavily tilted to low-income and homeless people.

Won’t all the homeless be driven out of their shelters and low-income housing disappear once price pressures hit area real estate?

“Not a chance,” says Bill Hobson, the executive director of the Downtown Emergency Service Center. “At the end of the day, I hope these new forces will understand that the people who operate the Frye and Union hotels are not going to go away.”

“I don’t think it will make it harder to do social services,” says Rick Friedhoff, executive director of the Compass Center. “I think there is going to be some friction between the haves and have-nots.” But he adds that with more upscale residents arriving, that may work to the advantage of the have-nots. With a population highly skewed to low-income residents and homeless, he says people often prey on one another and increase each other’s problems. “If they have to meld into a larger [and more diverse] population, they become a bit less lost and become healthier. Homeless people are very adaptable.”

Both point out that most low-income providers in the area, including the Frye Hotel at Third Avenue and Yesler Way, own their own properties and that many of their loans are backed by city funding that’s not likely to disappear.

That’s an assessment echoed by numerous city officials.

But will any of these low-income types be tolerated on the streets and in local open spaces?

Last month, soon after construction began on the building at Second Avenue and Yesler Way, a group of alleged crack dealers appeared outside the Lazarus Center, a homeless shelter, at the same intersection. Residents in an adjoining artist loft building took exception to their presence, especially late at night. Words were exchanged. Rocks were thrown at windows in the loft building.

The next day, a woman emerging from the building allegedly was told that she would be killed, according to Craig Montgomery, executive director of the Pioneer Square Community Association.

Soon after, a sign appeared on the artists loft. It said, “Welcome to Our Open Air Drug Market.” Montgomery said the uptick in drug dealing made the area worse than the notorious crack alley around Pike Street and Second Avenue. Seattle police discounted that claim.

Montgomery soon had staffers on the sidewalk across Second Avenue from the Lazarus Center with a video camera. One day, one of the videographers taped a man in front of the Lazarus Center reaching into a red backpack and handing something to another man crouched on the sidewalk. The second man is seen on the tape, soon after, lighting a pipe and exhaling a large cloud of white smoke.

Montgomery’s organization complained to Seattle police. In recent weeks, there has been a prominent police presence near the Lazarus Center. And the dealing appears to have stopped.

There have always been drug deals and street fights and homeless people hanging out in Occidental Park, all part of the weirdness that made Pioneer Square attractive to people who found the more benign street culture of West Seattle, for example, oppressive in its way. But it’s a part of the “Seattle Way” that rich recent arrivals to neighborhoods try to eliminate the very seediness that appealed to them in the first place.

One symbol of that occurred in March. Under pressure from area neighbors, the city cut down 17 old trees in Occidental Park, ostensibly as part of a park rehabilitation. But residents knew the score, as one neighbor, Pat Burke, explained to the Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

“Almost anything (the city) could do would be an improvement. (The park) has been such a disgrace. On the north side is where the mentally ill people congregate, and the south side is where the drug dealers hang out.”

Compared to just about any other large American city, it’s hard to believe that hard-core urbanites could find Pioneer Square frightening—try San Francisco’s Tenderloin District, for example—but Seattleites have long acted spooked by the neighborhood. With occasional drive-by shootings and last year’s beatings outside the former Larry’s Nightclub (closed earlier this year after its liquor license was pulled), Pioneer Square has long fought the perception that it is the city’s core public safety problem.

One of the Seattleites who has problems with the area is City Attorney Tom Carr, who recently complained bitterly about being panhandled aggressively at a bus stop in the neighborhood. Another is Montgomery of the Pioneer Square Community Association, who regularly carps about low-income residents of the Morrison and Frye hotels, many of whom hang out near the Prefontaine Fountain at Third Avenue and Yesler Way, whom he alleges commit all manner of street crimes.

They are a disheveled and beaten-down looking bunch, sure, but most seem to be doing little more than amusing themselves outside buildings in which they inhabit teensy apartments. Are they supposed to stay indoors 24 hours a day?

Bif Briggman, an owner of Laguna Pottery, who fought the “improvements” at Occidental Park, is a longtime Pioneer Square resident who says he’s troubled by the coming influx of prosperous residents.

“Telling us that trees caused crime and benches caused homelessness is a piece-of-shit argument,” he says. In the tree-cutting and talk of increased building heights, Briggman senses that the city has shunted aside established mom-and-pop business owners in the neighborhood, who stuck with the area through the worst of times, in favor of developers who are lining up to reap what comes of the good times.

“No one plundered before the way that it is happening now,” he says. “I’m not sure who can afford to live here anymore.”

Skolnik, the first manager of the Pioneer Square National Historic District in the 1970s, says he is concerned as well, principally that the city and developers don’t realize what a jewel they have, rather that they see it more as a disconnected, quasi–red light district. Pioneer Square is locally protected as a preservation district.

“They don’t look at the Square as having a theme,” he says, poking at the old idea that Pioneer Square should be the city’s arts district. “I would reinforce that theme and run with it.”

Like others, he notes that in recent years, artists have been chased from their studios and galleries from their spaces by dramatically increasing rents in the neighborhood (see “Occidental Exodus,” March 29).

Skolnik has concerns about the proposed North Parking Lot development as well.

“If you just fill it with housing, it’s not unique to the Square, and it ain’t going to be cheap,” he says. “And Pioneer Square is still left with, ‘Who am I?'”

That’s the big question that has always hovered over Pioneer Square. Is it a dumping ground for the homeless? An incubator for small businesses? An arts district? A tourist destination for out-of-towners to take the Underground Tour?

Crosier, the departing general manager of Doc Maynard’s, says that all the expensive new housing may be the last best hope for the neighborhood in a raw economic sense, but everyone should be careful what they wish for.

“The people in those expensive condos may call the cops cuz they don’t like the noise,” he says. “But these people have got to want to do something at night. If they don’t want nightclubs, then those places will convert to sports bars and lounges. The hottest club in the Square right now is Cowgirls. It’s just not Pioneer Square.” He means it’s a club that might be better suited to Bellevue.

But then, there are some things that will always be Pioneer Square.

One night on Memorial Day weekend, an employee at Fenix Tattoo on First Avenue South chased a man from the store and followed him a few doors south to where he had a small foam mattress in an alcove.

“You want to know why I’m kicking you out?” said the store employee. “Because I’ve got fucking standards. That’s why.”

The homeless man crouched on his mattress. It was then that the skies opened and a deluge of rain came down amidst the grand old buildings that will always be there to somehow moderate the character of the neighborhood, no matter how much change comes as the city tries to fit 2,000 more urbanities into Seattle’s original urban village.

Pioneer Square Projects

1. Alaska Building, Second Avenue and Cherry Street. City offices being rehabbed into apartments and retail.

2. Yesler Way and Second Avenue. 13 story building under construction now.

3. Yesler Way and Second Avenue. Rehab above Lazarus Center.

4. Occidental Avenue and Washington Street. Greg Smith/Urban Visions project. 12 floors.

5. North Parking Lot. Two towers, 400-plus units.

6. Seattle Plumbing building. First Avenue and Railroad Way. Five stories, 69 units.

7. WOSCA site. Tentative for the more distant future.

8. Commercial/retail/residential possible over tracks along Fourth Avenue South.