More than one hundred people filled the downtown lobby of City Hall Monday to celebrate Seattle’s third annual Indigenous Peoples’ Day—the holiday that has superseded Columbus Day in Seattle since 2014.

People from American Indian tribes from around the country attended, with members of local tribes dressed in the traditional Northwestern red and black robes adorned with buttons and woven bark hats. Drumming, singing and dances bookended speeches by local politicians and author Sherman Alexie, the speeches punctuated by enthusiastic shouts, beating on drums, or cries of “We are still here.”

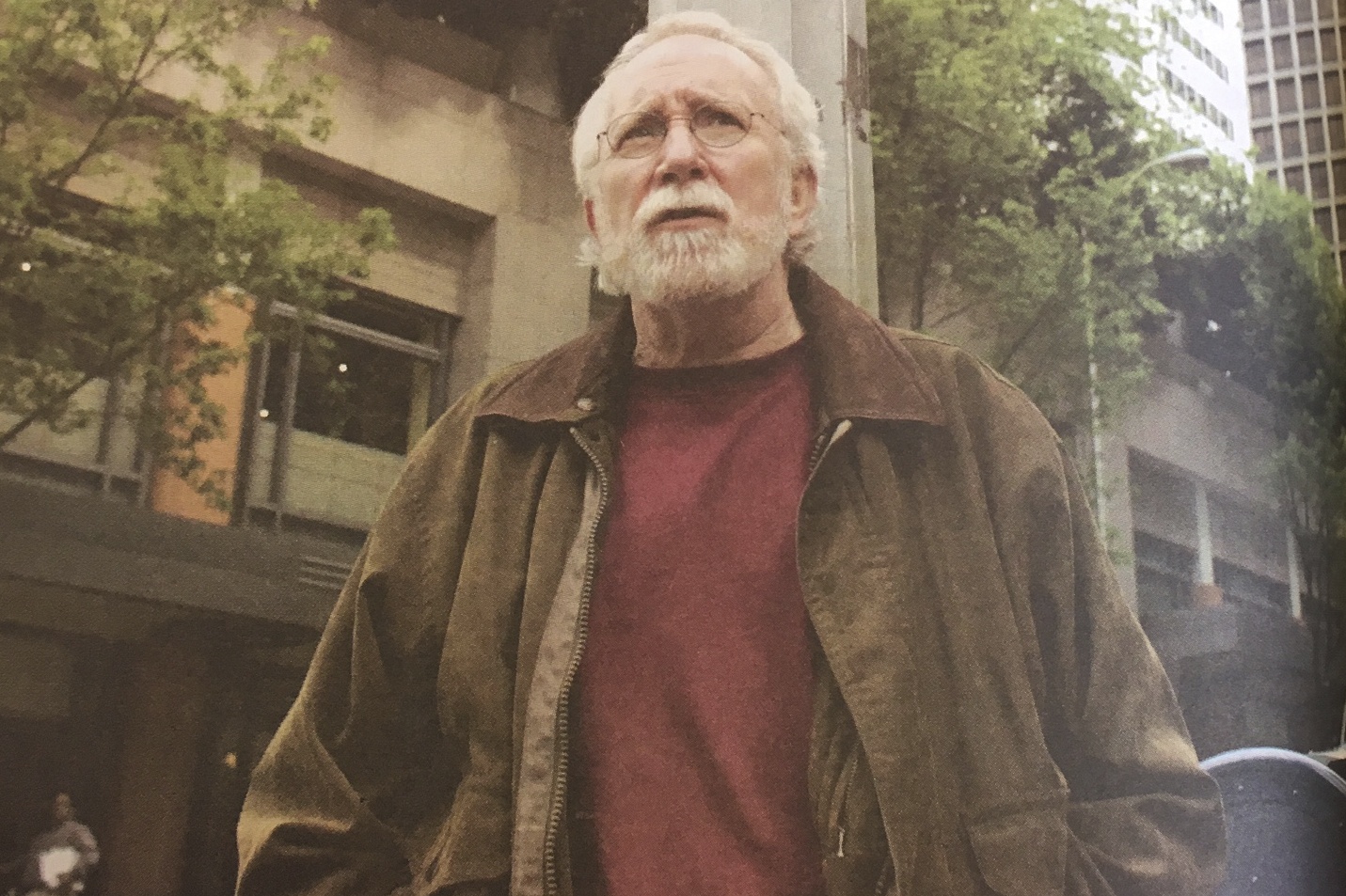

Alexie, who grew up on the Spokane Indian Reservation, told funny stories and sad stories, jokes and memories before he came to the significance of Indigenous People’s Day for him.

“One of the most dysfunctional things we Indians do to ourselves is teaching ourselves that it’s tough to live in two worlds. Bullshit. It’s magical. I don’t live in two worlds – I live in 187 worlds,” he said. “The thing is, I am Indian on purpose, I am Indian on accident, I am Indian reflexively, I am Indian consciously, subconsciously, unconsciously. I dream Indian, I nightmare Indian, I walk Indian, I sing Indian, I drum Indian, I tell stories Indian. And now we have a city that celebrates that in all of us. I’m proud of you Seattle. I’m proud of all you white liberals and you free libertarians, and that one Republican in here.”

When the Seattle City Council unanimously voted to recognize Indigenous Peoples’ Day as a replacement for Columbus Day in summer 2014, it was only the beginning. The resolution, drafted by activist Matt Remle with input from members of the local Native community, also included language encouraging Seattle Public Schools to adopt a curriculum that included tribal history. The following year, Remle drafted another resolution, to acknowledge the trauma of the Indian boarding school policy and its forced assimilation of Native Americans, including in Seattle. And three weeks ago, the Seattle City Council voted unanimously to stand behind the Standing Rock Sioux in their struggle against the Dakota Access Pipeline, which they believe would harm their sacred historical sites and water they depend on.

The pipeline protest played a prominent role in Monday’s events, with large banners carrying the slogan of the movement: Water is Life.

Remle, who lives in Seattle but is a Sioux from Standing Rock, held up the tribe’s flag throughout Monday’s celebration. For him, Indigenous Peoples’ Day is connected to larger struggles that Native Americans face, foremost among them the Standing Rock Sioux’s struggle to halt the pipeline that would pass within a half mile of their land.

“I like to say it’s like a puzzle, and there’s various pieces to the puzzle that’s decolonization,” Remle said. “So Indigenous Peoples’ Day is a part of that, the fight against the pipeline is a part of that. The fight that the Lummis are having against the coal trains is all a part of that.”

The struggles Native Americans fight against are nothing new, Remle believes, but what is new is the stronger relationship he’s seen between Native and non-Native communities since Indigenous Peoples’ Day was adopted two years ago, “and a greater willingness on the part of especially the non-Native community to be open and receptive to the issues impacting Native communities.”

Kshama Sawant, who took the lead in sponsoring the original Indigenous Peoples’ Day resolution in 2014, read from the list of 23 new municipalities and two states (Alaska and Vermont) that have made the switch to Indigenous Peoples’ Day since 2015. The most recent of them include Santa Fe, Denver, Yakima and Phoenix (the largest city in the United States to do so).

“When we came first together on Indigenous Peoples’ Day we also made the point that this is not a question of only recognizing the racism that existed in our history but also recognizing that that racism and the practices today and the prevalent economic, racial, gender inequality has ongoing consequences on the standards of living of entire communities, and whether or not they get to live in dignity,” Sawant said.