Carl Sander must be messing with me.

“Who is Ed Comet?” I innocently asked him.

The gray-haired, bespectacled man has been staring silently out the window for a full conversational minute. Cosmically, a minute might not seem long, but in a conversation, it’s an eon.

I look out through the glass of the hamburger shop we’re in to make sure the President, Macklemore, or Ed Comet himself hasn’t just walked by. Nope, nobody is out there.

“Take your time,” I tell him awkwardly.

“I’m just trying to think of a good yarn about Ed,” Sander replies.

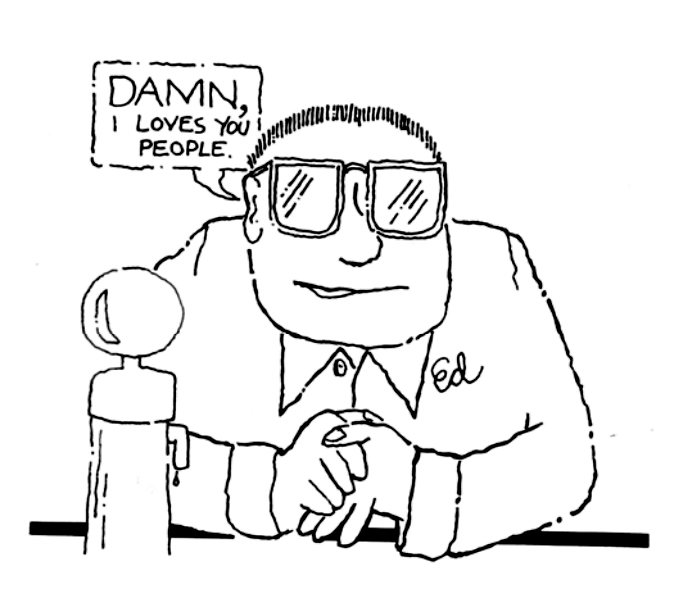

I look down at the drawing of a pudgy little cartoon man with a buzz cut and aviator glasses that Sander has brought with him. “Ed” is embroidered in loopy lettering on the man’s shirt. “DAMN, I loves you people,” he says in a square speech bubble.

The cartoon spills from a binder full of memorabilia from Sander’s glory days at the Comet Tavern. There are black-and-white pictures of Sander’s actor friends caught mid-laugh—folks who used to put on shows at The Empty Space theater at 919 East Pike Street just across the way from the Comet. Back in the late ’70s, when Sander started drinking beer there, the Comet Tavern was a huge theater hangout on Capitol Hill, and stayed that way through the ’90s. When the curtain closed on a show at New City Theater, Freehold Studios, Alice B. Theatre, or the Broadway Performance Hall, the cast would immediately head to the Comet. They even had their own table, “The Actor’s Table,” a big, round, Arthurian thing by the front window that could seat 10. Sander, now the public programs manager at the Burke Museum, used to be an actor and a poet himself.

Sander’s poetry is actually the reason I’m here.

In 1938, Pike Place Market erected its famous neon sign. Sixty years later, in 1998, the Market decided it needed to replace 12 of the sign’s worn-out letters. As a publicity stunt, the Market held a poetry contest; the winner got to pick one of the 12 to keep, with the 11 others auctioned to the highest bidder as a fundraiser. Sander wrote the winning poem:

Under the Market Clock’s Neon

Knots and Noise

I Encounter True Love.

Sander chose the C, and decided he would donate it to his true love—the Comet Tavern. The wily Sander enlisted his friends Bliss Kolb and Gary Smoot to build a giant Rube Goldberg machine to unveil the C at the Comet party marking the occasion.

“There are some very clever, wonderful people who live in this city,” Sander says.

A schematic of the device is strewn across the table in front of me, drawn in pencil on a piece of 16-year-old graph paper. To start it, Sam Wright, then-owner of the Comet, poured a glass of beer into the contraption. Thus began a chain of reactions that raised a lit candle, which burned a rope, which released some pool balls, which then released a big tarp that revealed the giant neon C.

The neon letter has been there ever since, “permanently on loan,” hanging on the Comet’s back wall. Every time the Comet has changed ownership, Sander has tracked down the new owner(s) to vet them before permitting them to keep the glowing Pike Place relic. Dave Meinert and Jason Lajeunesse, the Comet’s newest owners, just recently received his blessing.

His minute of contemplation over, Sander finally answers my question. “Ed was on the rowing team from the University of Washington that won the Olympic gold medal in Berlin,” he says very slowly.

“You mean the one in Nazi Germany?” I ask him.

Sander nods. “He came back and started a family; I’m not really sure how he made his money.”

“Was he just a regular at the Comet?” I ask.

“I think I might’ve seen him once or twice. He was more of a . . . ”

Sander drifts off again.

“More of a what?”

Sander looks back out the window. “He was a spiritual guide of some sorts. I can’t define him. He was just a normal guy. He was inviting.”

I look back down at the drawing on the table. I try to imagine this doofy-looking cartoon man as an Olympic-gold-winning rower who defeated the Nazis before returning to Seattle to drink his days away in a dive bar on Capitol Hill, where he allegedly served as some sort of shaman.

“Well . . . what would Ed say to you?” I ask Sander. “What spiritual guidance did he provide?”

“Oh, I never talked to him. You should ask Sam Wright about him—I think he knew him better.”

When Sander leaves, I take out my smartphone and look up “UW Olympic Rowing Team 1936 Olympics.” An article pops up with a black-and-white picture of nine men staring back at me. They are wearing tiny shorts and jerseys emblazoned with the letter W.

The caption lists their names: Don, Joseph, George, James, John, Gordon, Charles, Roger, and Robert.

No Ed.

Carl Sander was indeed messing with me.

“Who is Ed Comet?” I ask Meinert and Lajeunesse. We are sitting in the 24-hour diner they own, Lost Lake. It’s just around the corner from the Comet Tavern, which as of November 2013 they also own.

Some people refer to these two and their cohort as “The Pike/Pine Mafia.” Meinert owns The 5 Point Cafe and is a co-manager at Onto Entertainment, the local managing company responsible for launching the Lumineers. Lajeunesse is the owner of the Capitol Hill Block Party music festival and co-owner of Neumos, Barboza, Pike Street Fish Fry, and Moe Bar. Together, Meinert and Lajeunesse co-own Lost Lake Cafe and Lounge, Big Mario’s New York Style Pizza, and now the Comet Tavern. They are very good at what they do.

“From what we understand, Ed was a caricature of a Comet regular,” Meinert says. “They used to use him in a bunch of Comet ads in the newspapers like The Rocket and the Weekly, I think. I don’t know when they stopped. I don’t think they’d used him recently.”

Meinert and Lajeunesse have been collecting historic photos and documents from the Comet’s past to hang up when they reopen the place on March 31. Ed has popped up in many of the documents they’ve gotten from past owners and patrons so far.

“Where else can ya go and drink a beer like a normal person?” a cross-eyed Ed with a mustache exclaims from the top of an old “Backgammon Happy Hour” postcard that the duo dug up. The image of Ed with that same catchphrase appears a couple more times in other documents Meinert and Lajeunesse show me.

“I have no idea if he was a real person,” Meinert says. “Sam Wright would know more about him—have you talked to him yet?”

When it was shuttered last fall, The Comet Tavern was the shittiest, scummiest, craziest place on Earth to see live music. Rakish blonde punks covered in tattoos and leather jackets seemed to run the place, a place with a bathroom notoriously filthier than the inside of Satan’s anus. The sound system was terrible and the cheap beer was even worse, but that was sort of the charm. To top it all off, it was booked by a woman named “Mama Casserole.”

“One of the earliest bands I booked there were the Jailbirds, this rockabilly band from Japan,” Mama tells me, flashing back to the start of her booking days in 2004. “They had long cords on their guitars, so they just jumped up on the bar and played there.”

Part of the reason the Jailbirds, and many bands at the Comet, might’ve played on top of the bar is that for most of the tavern’s music-venue days there wasn’t really a stage. Up until one was installed two years ago, there was merely a tiny wedge in the corner, only big enough to fit one drummer.

The drummer still got to have fun, though.

“Monotonix almost lit fire to the place,” Mama says, referencing the Israeli rock band’s 2008 show. “They lit fire to their bass drum, and the drummer was holding it up in the air and banging it around. I was like, ‘Oh, my God, the place is gonna catch on fire.’ Then they started playing outside. All the people in the crowd held the drummer up in the air with their hands.”

Seven nights a week, you could see live music at the Comet Tavern, thanks to the work of Mama Casserole. Anybody could play there. Das Racist, a hip-hop group from Brooklyn, would sell it out one night, then your roommate’s awful alt-country band would play there the next. If you had Mama’s e-mail, you were pretty much good to go.

“It was hard to book seven nights a week like they wanted me to and keep that integrity as a booker,” Mama says. “Honestly, on Mondays and Tuesdays I’d come by and the doorman would just sigh really big, look over at the band, and go ‘Mamaaaaa . . . ’ If you wanted to work there, you had to put up with some bad shit sometimes.”

Despite that, the Comet Tavern’s reputation and lore is as thick as the beer stains on the floor. When Mama was in Rome on vacation once, she noticed the bartender was selling microbrews, unusual for Italy. She asked him about it, and he said he’d gotten the idea while in the Pacific Northwest, where he and his band “played a show at this crazy place in Seattle with a big light-up C.”

“You’d see so many passports at the door,” Mama says. “It was internationally known as this Seattle institution.”

Part of the reason the Comet Tavern had that charmingly divey, constantly-about-to-collapse feel is because it actually was about to collapse. Mama didn’t book seven nights a week because she wanted to. She did it, she says, because owners Chris Dasef and Brian Balodis would’ve gone out of business if she didn’t.

“They just didn’t care at all, they just wanted to get the money from the shows,” Mama says. According to multiple sources, Balodis, a banker who bought the bar from Dasef in 2007 on something of a whim (he claimed he didn’t really hang out there before), botched his role as an owner in almost every way.

By the end, Balodis even failed to pay his waste bill. Dumpsters outside sat crammed full of ancient beer-soaked trash. And then, last October, the Comet Tavern finally did collapse, abruptly closing its doors. That’s when Meinert and Lajeunesse came in and bought the lease.

“The Comet sort of signifies the soul of this street,” Meinert tells me. “We were afraid to lose that soul. In some ways we felt if that goes away, the street kind of tumbles away to become something very different.”

A lot of people might think it’s funny to hear Meinert say that.

A month ago, he and Lajeunesse posted the first pictures of the Comet’s extensive renovations on the bar’s Facebook page, prompting an onslaught of outraged comments:

Nice, I hope all the douchebags that will patron the joint enjoy all that history we made.

Miss the old bar! Looking a bit too swank to be the Comet, crying inside.

Make sure to get all the soul out of there.

Inquiring minds want to know why the new owners are doing away with the Comet’s long tradition of supporting live music? Is there any truth to the rumor that live music will only be Tuesday nights (the worst bar night of the week)?

Indeed, there is truth to the rumor. The Comet Tavern will no longer be a live-music venue. There will be no stage. Bands and DJs will play on the floor a couple of nights a month, but that’s it. The bathroom is completely new—clean as Jesus Christ’s anus. No more rotting floorboards or vomit stains on the wall.

Then there was this comment: RIP the Comet 1950s–2013.

Turns out there is not as much truth to that comment: The Comet Tavern was actually born in the ’30s, and it has “died” many, many times.

Above: When George Commet opened the tavern in 1932, it was half the size it is now—the eastern portion of the bar, annexed by Jim Martin during his ownership in the mid-’70s, used to be a separate storefront called Cornwall Tool Company.

A man named George Commet established what we now know as the Comet Tavern in 1932 with a bar, some booths, pinball machines, and a jukebox.

Even before that, around 1900, it was called The Wee Deoch and Doris, a little ma-and-pa Irish bar. Back then, Capitol Hill was pretty barren. In 1905 the first automobile dealer opened, and by 1915, almost all the city’s car-related businesses had moved into the neighborhood, which took on the nickname “Auto Row.” Tunnels ran under some of the neighborhood’s buildings, connecting repair shops to auto dealers so parts could easily be moved back and forth. When Prohibition hit, people snuck into the basement of The Wee Deoch and Doris and drank illegally in those tunnels. The tunnels have since been sealed.

In the ’50s, the Comet was mostly a blue-collar bar for older folks. Newspaper records from The Seattle Times report a couple of stick-ups and robberies at the tavern around that time, but it was pretty quiet for the most part. When your average Joe would get off work from the auto shop, he’d go to the Comet. It was your friendly neighborhood bar. It was not a mythological palace of debauchery quite yet.

Then the ’60s hit, and like most things in the ’60s, the Comet got a little weird.

Around that time a new owner, Dick Worthington, decided to paint the windowpanes black, and suddenly it became “an acid bar,” according to a number of the Tavern’s later owners. Older regulars weren’t too happy. This might be considered the first “death” of the Comet.

“The decision was made before I got there that they wanted a younger clientele,” says Fred McDonald, who co-owned the bar from 1972 to 1974 with Worthington. “They hired younger bartenders to scare the old people out, and a lot of hippies started hanging out there. You know, long hair and everything.” The upstairs portion of the bar was dubbed “The Cloud Room,” a place where people could go and smoke weed.

By the time McDonald installed the famous “Comet Tavern” sign out front, the place was a bizarre melting pot of those old blue-collar workers, hippies, and everyone in between. “It was unpretentious,” McDonald says; “it was comfortable. Anybody and everybody was welcome.”

The night Nixon resigned in ’74, the Comet Tavern handed out free beer to celebrate. A reporter from The Seattle Sun, Bruce Olson, was on hand to report on the jubilant, strange scene:

Jack Voltaire, sweat pouring from his 65-year-old face, his Hawaiian shirt open to the third button, stood in the middle of the Comet Tavern last Thursday night bellowing ‘This is a GREAT day for communism!’ The president had resigned, the beer was free, and the Comet, a long-time Capitol Hill hangout for burned-out radicals, assorted carpenters, artists, and unemployed journalists, was exploding with toasts, cheers, and obscenities.

Jim Martin, the owner after McDonald, apparently ran around that night in a yellow construction hard hat. Sometimes people ran around in there not wearing anything at all.

And/Or was an artist-run nonprofit in the mid-’70s, right around the corner from the Comet, where Oddfellows Cafe now resides. Nationally renowned avant-garde performers like Laurie Anderson, Judy Chicago, Terry Riley, and Harold Budd all came through the space—one of the few places in town with a house Moog synthesizer.

Along with all the actors from The Empty Space across the street, folks from And/Or would hang out at the Comet, including Cathy Hillenbrand, who at the time was unhappily practicing law. When the Comet went up for sale, her then-boyfriend mentioned “it might be fun” to buy it. It made complete sense to jump ship and run the bar all her friends were at anyway.

Two years later, she started interviewing patrons, collecting their memories for a personal project called “Ed Comet Remembers.” She’s lost most of the tapes, but one story about a particular day in the early ’70s sticks out because she heard it multiple times.

“Apparently, the bartender at the time came in and decided that day he was going to get completely naked except for an apron he put on. For that particular day, he just decided to institute the policy that if you wanted a beer, you also had to strip. More than one person told me the first time they ever went to the Comet was that day.”

Hillenbrand had a few debauched nights at the Comet herself. In 1976, a year before she bought it, she was present for the event that first launched the Comet into the national spotlight—a televised mock debate between Chip Carter (the son of then-Presidential hopeful Jimmy Carter) and a college student who debated as “Jack Comet,” the son of Ed Comet. The debate whipped up controversy thanks to the televised images of the candidate’s son drinking Cuervo tequila straight from the bottle, which violated state liquor laws mandating that taverns could serve only wine and beer.

Above: Chip Carter drinking “tequila” at The Comet on national television.

Carter denied there was real tequila in the bottle, claiming it was “only a prop, and, in fact, had flat beer,” according to the Ellensburg Daily Record. “One of those who drank from the bottle—who wished to remain unidentified—could not recall whether the bottle contained flat beer, tequila, or water,” the article ends.

Hillenbrand can’t really remember anything from that night either. “It’s pretty hazy. I remember it ended with me dancing on top of the bar, though. I don’t know why the debate was in Seattle or at the Comet. The Comet was just a magical place. Crazy, wacky stuff happened there.”

“Who is Ed Comet?” I ask Hillenbrand.

“Supposedly the bar used to be owned by a great guy named Ed something? I honestly don’t know. Robert Horsley—he owned a print shop up on 19th—he did the original drawing and created the character Ed Comet, but I don’t know the origin story.”

Hillenbrand grins. “You should ask Sam Wright about him.”

Above: Sam Wright, on the right.

“You’ve reached the Wright residence at the wrong time, leave a message.” I heard that answering machine over and over and over before Sam Wright finally picked up. A week later I am sitting across from him.

“Everyone keeps saying I should ask you, so . . . Who is Ed Comet? Was he on the Olympic rowing team in 1936? Or did he used to own the place?”

The 54-year-old with wide-set eyes starts laughing at me. “I told all my employees, and the hundreds of people I hired over all those years, ‘If anybody asks you about Ed Comet, you can tell them anything you want except the truth.’ The more convoluted the story, the better,” Wright says. “Ed was my favorite part of the Comet. The look that he had. And his famous saying, ‘Damn I loves you people.’ He just looked like a regular Joe having a beer. I thought it created a picture of what the Comet was really like inside. ‘Where you can be anything but an asshole.’ That’s what we used to say about the Comet.

“And there was a lot of that happening back then, too. There were places where you weren’t welcome if you were black, gay, you know . . . pick your thing. It’s not the case now, but it was then. If you were a hippie, there were places that wouldn’t let you in.”

Of all the chapters in the Comet Tavern’s history, Sam Wright’s saga is easily the longest, and quite possibly the most lyrical.

It began with a lady. Three ladies, actually.

The first was Sam’s girlfriend, who worked at the Comet, then under the ownership of Hillenbrand, and who regaled Wright with stories about how wonderful the place was. “So I went to go check it out and ended up loving it,” Wright says. “And I met this older lady, Ethel, this legend, the patron saint of the Comet.”

Today Ethel O’Hearn is literally a part of the Comet Tavern. Her ashes are inside one of the bar stools, marked with a brass plaque bearing her name. It’s a fitting resting spot. Ethel lived upstairs above the Comet for most of her life.

Above: Ethel, embraced by a couple of regulars.

“I loved her,” Wright says with a sweetness in his voice. “She was very much like you might suspect a 72-year-old woman who had been hanging out in bars for the last 40 years and chain-smoking to be like. Horn-rimmed glasses. Short, little, bent over. More than once she’d thrown big, scary guys out for me. She’d grab them by the ear and push them out the door, guys that would’ve torn me apart given the opportunity. They wouldn’t mess with her.”

Ethel had been working the door since at least 1972. Fred McDonald fondly remembers her checking IDs and telling almost everyone who walked in, “The older I get, the younger you look.”

Ethel is the reason Wright got a job at the Comet. She realized that at her age, any hours she worked would get taken away from her Social Security, so she started giving Wright a couple hours on Sundays when he turned 21 in 1981.

“Our relationship was very jovial—I used to call her ‘Her Oldship,’ ” Wright says. “I’d do the kowtow with the whole regal twirling-your-wrist thing. She was so well-liked by the people who came there. We used to have this thing where if you wanted to buy someone a drink, we’d have markers—you’d overturn a shot glass. Sometimes she’d end up with a pyramid you could park a car on top of made out of overturned shot glasses.”

Ethel was also friends with Wright’s mother, a bookkeeper for Hillenbrand at the time. When Hillenbrand decided to sell the Comet, she tried her best to give it to Ethel. Ethel wanted nothing to do with it.

“I went on pushing her for a while,” Wright explains. “I could understand why Ethel didn’t want to go in on it, but she finally said she would if I could convince my mother to become a third partner.”

On the first day of 1982, a little less than a year after he’d turned 21, Sam Wright suddenly found himself a co-owner of one of Seattle’s most storied bars, alongside his mother and a chain-smoking elderly woman who downed pyramids of free shots.

“I was elated,” Wright says. “I had no clue what I was doing.”

Wright would remain at the Comet for almost a quarter-century. He started that stint by “killing the Comet” a second time—reversing what “killed the Comet” the first time and scraping all the black paint off the windows.

“I might as well have just locked the doors. They thought I’d just ruined it. You don’t understand—when you’ve got something like that that you like, change is not good. No matter what kind of change it is, it’s not good. That’s what people think initially. They all came around to it after that, after the fact. ‘Maybe the light ishhn’t so bad? Maybe having . . . shhumm windows, maybe it’s OK,’ ” Wright says in a mock drunken slur.

“Letting the light in made the place seem twice as big. What’s wrong with that? It also allowed people to see that something was going on inside. Which is also good.”

One day Ethel started telling Wright stories about the old days. She said the Comet used to serve free turkey dinner for Thanksgiving.

“Why the hell don’t we do that now?” she asked Wright. So in his second year of owning the Comet, Wright took Ethel up on her challenge.

April 7, Ethel’s birthday, became “Ed and Ethel’s Super Famous Chili Day.” Wright and his wife at the time would make enormous pots of chili, dumping in $100 worth of ingredients and serving it free to whoever knew to come in. On Thanksgiving he served free turkey dinner prepared in his “janky-ass turkey cooker,” as an employee of his explained it. On Christmas, he would serve free ham dinner to anyone who needed it.

I ask Wright why he was driven to spend so much on charitable dinners at his dive bar.

“It struck me that the kind of people that were in a bar on Christmas Day, you know, as a general rule they could probably use a Christmas dinner. It wasn’t all my doing . . . it was Ethel’s idea, really . . . ”

Tears begin to well up in Wright’s eyes. “Sorry, I’m starting to get misty thinking about Ethel. I haven’t in a long time,” he says.

Ethel died in 1984 on April Fools’ Day from a gangrene infection she picked up after a trip to Las Vegas with her friends.

“It was horrendous,” Wright says. “There was a big wake, everybody took it very hard. People mourned for a large amount of time behind large amounts of alcohol. That’s just the way it was done.”

“Sam was an incredibly generous man,” says Jason Finn in his raspy voice. “You really couldn’t ask for a better boss than him. The Christmas bonuses he gave were insane. I worked every single Christmas because my family’s Jewish, and every Thanksgiving because my family would get done early. There would be 40 people there having turkey sandwiches every Thanksgiving. All of that was straight out of Sam’s pocket. Everybody couldn’t wait to come in—they’d be taking their ties off going ‘Ahhh, my fuckin’ parents.’ ”

Most people know Finn as the drummer of the Presidents of the United States of America, the Seattle band whose self-titled debut album, released in 1995, went triple platinum. Aside from the Presidents, Finn has had only one job in his entire life: working at the Comet Tavern.

“In the late ’80s, I was part of a group of young people who were going to the Comet,” he says. “Many of us were underage. Including me. It was a place you could get into. This was a transition time for the Comet in that it had been kind of a logger’s bar. Tough guys. People we thought of as older—they seemed 100 years old. Nobody our age was working at the Comet at that time.”

In 1988, Finn was one of the first people of his generation to score a job at the Comet. Others followed.

This was the third “death of the Comet,” depending on whom you ask. Finn and his friends would get in occasional tiffs with the older patrons who sensed they were getting phased out, thanks in part to the strange, heavy music that started blaring out of the sound system on a semi-regular basis. One gentleman even went so far as to dump his pitcher of beer on Finn’s co-worker’s head. “You guys have ruined this place,” he told the young man.

Sub Pop was just two years old then—Finn’s band Love Battery was part of the second wave of local singles the label had put out, starting with the band’s song “Between the Eyes.”

“I think that whatever larger demographical things that were happening in town, it being kind of an exciting time for music and arts, it was just a right time, right place for the Comet,” Finn says. “All of a sudden everybody was in a band. It wasn’t that it was ‘the band bar,’ but it was one of the only bars, and everyone was in a band, so of course there were a ton of musicians in there. Anyone you would care to name from the regional Sub Pop roster at least poked their head in.”

Well, except Kurt Cobain. Krist Novoselic would come in, but Cobain would sit in the van out front, smoking cigarettes and staring off into space, never setting foot inside.

The late ’80s to mid-’90s was one of the busiest periods in the Comet Tavern’s existence. “It was crazy,” Wright says. “Just the sheer volume of people packed inside there every night was nuts.”

Next to the Washington State Ferry System, the Comet had the state’s largest Rainier beer account. Finn had to slam empty pitchers on the tables by the end of the night and scream “GET OUT OF HERE! YOU GOTTA GO!” to get the packed bar to disperse.

It was a bittersweet time for Wright. After Ethel’s death, things were dark for a moment, but Wright’s love for the Comet prevailed. He fell back in love with Ed, taking joy in the weekly newspaper ads he ran featuring the bar’s mascot.

“We never advertised because we needed to,” Wright says. “We just did it for fun. Lots of different people would come up with the stuff he would say. I came up with a lot of them. One of my favorites—Ed was sitting at a dinner table with a pilgrim hat on, surrounded by a huge big spread, so it was obviously Thanksgiving. He has this big shit-eating grin on his face, and he’s just saying ‘Thanks.’ ”

Regulars loved Ed and loved Wright. The Comet’s pool league took off, the sign-up chalkboard becoming so cluttered that people devised intricate ways to sneakily scoot their name up the list when nobody was looking. By the mid-’90s, Comet fever reached its height when Hale’s Ales debuted its “Ed’s Ethel Ale,” bestowing the ultimate honor on the bar by creating a namesake brew complete with a custom tap and a neon sign featuring Ed’s likeness.

But by the time the Comet unofficially became the “grunge hangout of the Northwest,” Wright stopped wanting to hang out there quite as much. “That was one of the first things that kind of pushed me in the direction where I didn’t really want to go there at night to have fun anymore,” Wright says. “They would play some music in there I just could not believe anybody would pay money to listen to.”

Until then, the Comet deliberately had never been a music venue. The only band that played there was a funk band from Portland called Slack, for whom Wright had a soft spot. But by the time Finn permanently left the Comet in ’95 for a massive POTUS tour, the tavern and Seattle in general was an entirely different place. The influx of people moving to Capitol Hill placed unprecedented pressure on the Comet—which until then had done gangbuster business with little effort, since it had always been one of the only places in the neighborhood to get a drink. But that changed with the addition of the Cha Cha Lounge and Linda’s Tavern, the first of a wave of new bars on Capitol Hill. Then the building’s landlord passed away, and the new owner increased the rent sevenfold.

By the 2000s, things were getting rocky. Pressure began to mount from Wright’s music-minded patrons to start hosting shows to bring in money. Mama Casserole, then a relative newcomer, led the charge to get live music in the place.

“As soon as you put music in, I knew it would cease to be the neighborhood’s living room,” Wright says. “It’s not your living room if there’s a loud band in it.” In fact, all the owners from the ’70s on had experienced similar pressure, but were able to resist hosting live music.

“My employees were going on and on about how this is what was going to save us, this is what’s going to make it vibrant,” Wright recalls. “I think it started when I finally agreed and said, ‘OK, you can do it one Sunday night a month.’ I hated it.”

The final straw came one night in 2003, when Wright dropped by and found 15 or so people standing outside the Comet, the bartender included. Nobody was inside except for the band, who were wearing nothing but diapers. “I thought, ‘Yeah, OK. This is going in the wrong direction.’ ”

In 2006, Wright sold Chris Dasef the Comet Tavern, which very soon became a seven-nights-a-week music venue. When Finn heard that the Comet had started hosting shows, he was incredibly angry. “The Comet was not a special venue,” Finn says. “It was a special tavern.”

By the time Brian Balodis took over, Wright was disgusted. “People didn’t respect the place at all. They were kicking in the walls. You could hock a loogie on the mirror and put a cigarette butt out on it, and it would stay there the whole week. Even though the place was always a dive, we prided ourselves on the fact that it could pass a white-glove test.”

This was the fourth “death” of the Comet.

It’s now early March and a man on a ladder with a power tool is chipping away the paneling on the eastern portion of the Comet Tavern, helping to carry out the place’s latest “death.” As the plaster falls, brick appears behind it.

“We found out there’s a bunch more old brick back there that got covered up in the past for some reason,” Meinert says. “We thought it looked really cool, so we’re trying to expose more of it.”

Meinert and Lajeunesse are giving me a tour of the new Comet. It’s a lot different. There is no stage. Everything is clean. I would eat off the toilet.

But in a lot of other ways, it’s familiar—it looks like how all the bar’s owners before 2006 described it to me, pool tables, pinball, booths and all. A table much like the one Carl Sander and his actor friends hung out at sits near the front window, replacing the sound booth that most recently lived there.

“When we first got here, there was a lot of urine,” Lajeunesse tells me. “All the drywall was soaked. Anywhere there was water or plumbing that had touched something was completely rotted. The Comet was a punk venue, and like true punk rock, it burned to the ground. Just complete and total devastation. All the drywall and plaster surfaces in the entire place were kicked in. First we were like, ‘What can we keep? Let’s try not to do too much.’ But then we got the keys to the place, and realized how much physical destruction had been done to the bar. There was not a whole lot to keep anymore.”

Meinert explains that he and Lajeunesse are trying to create a “best of” the Comet’s past, including an array of cheap beers on tap.

Lajeunesse and his employees are busy framing all the old prints and ads they’ve gathered; the plan is to hang them upstairs in the old Cloud Room as a sort of museum of the Tavern’s history. In one ad, Ethel peeks out from behind a tall man with his arm around her shoulder. Cathy Hillenbrand stands second from the left, looking like quite the ’70s bohemian. “Where’s Ed Comet? The Real Comet Tavern,” it reads.

Before I left my conversation with Sam Wright, I asked him the same thing. “Where is Ed Comet? I haven’t seen him since I started hanging around the Comet Tavern.”

“I took Ed when I left,” Wright said. “That was really the only thing I wanted to keep. Now the original lives in my basement.”

“Why?”

“Ed was the Comet,” Wright told me. “He was the Comet the way it was, the way it should’ve been. I think one of the great things about the Comet is that it appealed to the common, less-than-rich subculture person. You know, Ed. It was a poor man’s hangout. It’s hard to be a poor man’s hangout in a rich man’s neighborhood.”

“Do you think you’ll give him back to David Meinert and Jason Lajeunesse?” I asked.

“I might.”

As I continue to poke around the new, spiffier Comet, Meinert calls my name from across the room. “Hey, you should check this out, too.”

Over on the huge exposed-brick wall, Meinert points to a faded painting of a very ordinary-looking man smoking. “This graffiti someone did of Ed Comet is one of the few things on this wall that survived. I think we’re going to frame it. Pretty neat, right?”

Some plaster getting stripped off the old brick falls from above. We both look up.

ksears@seattleweekly.com