Two of Spc. Brandon Barrett’s fellow Joint Base Lewis-McChord soldiers were killed and more than 20 wounded in three major firefights and suicide bombings the 5th Stryker brigade endured during its year in Afghanistan. Between the summers of 2009 and 2010, Barrett and his colleagues came under fire from snipers, mortars, and roadside bombs in sparsely-settled Zabul province, bordering Pakistan, and, to the south, in the Taliban-controlled Helmand province.

One particular firefight between the Taliban and Barrett’s 5th Stryker detail lasted five hours. “His unit saw some of the worst combat in Afghanistan,” says Barrett’s brother, Shane, a Tucson, Ariz., police detective. Firefights were so intense the Lewis-McChord soldiers were sometimes known as the Shit Magnets. “If it was bad and it happened,” a grunt told a reporter last year, “it happened to us.”

Brandon Barrett, who killed at least two enemy fighters during his year-long tour, didn’t seem to fare badly, however. During a post-deployment health screening last summer, he told doctors only that he was a bit nervous, could be startled from time to time, and had seen lots of dead people. Otherwise, he was fine, he added, and certainly not suicidal. But doctors, according to a 200-page Army report on Barrett’s case obtained exclusively by Seattle Weekly, worried he was keeping his real feelings to himself. He denied having any medical or mental-health issues, doctors noted, although they did refer him to the service’s substance-abuse program.

At that point in 2010, the stocky, bespectacled, 28-year-old unmarried infantryman with friendly hazel eyes and clipped brown hair had been in the Army four years, graduating from high school before attending community college in Tucson and working in a restaurant. He had kept his record mostly clean, save for the time as a teen he was caught smoking marijuana. The son of a Marine veteran, in 2006 he joined the Army, where, his Army records show, he was universally referred to as a “good soldier.” He learned to like military life, and happily discovered barracks full of fellow video-game addicts. Soldiers fight like men, but play like kids: Besides his PlayStation 3, Barrett favored the Xbox 360 and an assortment of combat-related games. He fired them up first thing whenever he came home on leave, says his family.

“That changed when Brandon came home” last July, says Shane Barrett. “Brandon didn’t play a single combat-related video game.”

The family just assumed he had matured and was over the video-game stage of life. What they didn’t know was that Barrett was AWOL. He hadn’t given up on gaming, but on the Army. The turning point began on the second day of his return to Lewis-McChord from the killing fields of Afghanistan. A sometime six-pack-a-day beer drinker, Barrett decided to get roaring drunk in a local bar, downing Jägermeister and beer.

Sometime before 3 a.m., en route to his barracks, he pulled his car partially off a base roadway, turned off the engine, and went to sleep. Within minutes, military police rapped on his window. They helped him out and arrested him for DUI. His blood-alcohol level was twice the legal limit.

He was both hungover and mortified the next day, friends said. The Army immediately took away his base driving privileges and scheduled him for court appearances, treatment, and likely punishment. A week later, a superior officer larded it on. During a company formation to discuss soldier-safety issues, he turned and addressed Barrett personally, who seemed dumbfounded. The soldier, the superior informed the company, had been busted for drunk driving. He had endangered himself and others. This was just what a soldier shouldn’t do, he told the others. To drive home his point, the superior said he was recommending that Barrett not be allowed to participate in the unit’s month-long home leave, a few weeks away.

Though he rarely showed his emotions, Barrett was crushed. He hadn’t seen his family in more than a year. Army buddies would later tell investigators Barrett was “livid” and embarrassed at being singled out. As he would tell a friend in a text message, he was “going to show them why they shouldn’t fuck with recently deployed soldiers.” Members of his company were worried. The Army didn’t seem to notice.

It was a chaotic time at Lewis-McChord, where a series of crimes and deaths prompted Stars and Stripes, the armed-forces newspaper, to call the sprawling Army post the “most troubled base in the military.” Five of Barrett’s Stryker brothers had allegedly murdered at least three civilians in Kandahar Province, Afghanistan, in 2009 and 2010. Some were shot in scenes staged with prop weapons to look as though soldiers had fired in self-defense. Army prosecutors say the self-styled “Kill Team” was the warped idea of Staff Sgt. Calvin Gibbs, 25, a high-school dropout from Billings, Mont., who collected fingers, a leg bone, and a tooth as mementos.

In an interview taped by the Army, one of Gibbs’ co-conspirators, Spc. Jeremy Morlock, 23, of Wasilla, Alaska, said Gibbs directed Morlock and another soldier, Spc. Adam Winfield, 22, of Cape Coral, Fla., to shoot a noncombatant in January 2010. Gibbs, Morlock said, lobbed a grenade “and tells me and Winfield: ‘All right, wax this guy. Kill this guy, kill this guy.’ ” Winfield told a similar story about a May murder of another Afghan civilian by the same threesome: “Sergeant Gibbs said, ‘This is how it’s going to go down. You’re going to shoot your weapons, yell grenade. I’m going to throw this grenade. After it goes off, I’m going to drop this grenade next to him’ . . . we’re laying there and Morlock told me to shoot, so [I] started shooting, yelled ‘Grenade.’ The grenade blew up and that was that.”

Seven other soldiers from the Lewis-McChord platoon were accused of covering up war crimes, impeding an investigation, and beating up a fellow soldier who blew the whistle on their hashish use. Court-martial proceedings for the dirty dozen began last year and are expected to run through 2011. The most recent hearing ended in a guilty plea by Morlock, who agreed to testify against Gibbs and others in return for a 24-year sentence with the possibility of parole within eight years. Asked by an Army judge last month if murdering civilians was an impulse, Morlock answered negative. “The plan,” he said firmly, “was to kill people, sir.” Widely published photos and videos of the Kill Team suggest the atrocities may be even more widespread; platoon members were known to shoot randomly at farmers working the low fields of Afghanistan, a country—dating back to Alexander the Great’s arrival—accustomed to invasion and conquest.

Joe Kubistek, a Lewis-McChord spokesman, says the Army “is a reflection of society, in some ways,” but makes no excuses for Gibbs and the others. He notes the accused killers are five among 40,000 uniformed personnel at the base south of Tacoma, the overwhelming majority serving with honor. “We got calls from soldiers who wanted to know how this could happen,” says Kubistek. “Everyone was upset. ‘This wouldn’t have gone on if that was my unit!’ they said.” The Army has apologized for the carnage shown in the killers’ trophy photos—including a victim who appears to have been shot in the back—and is seeking hard time for the accused.

“We don’t do this,” says Lewis-McChord prosecutor Capt. Andre Leblanc. “This is not how we’re trained. These are the actions of a few misguided men.”

The base also was in turmoil over claims that it mistreated members of an Oregon National Guard team that was demobilized at Lewis-McChord after returning from Iraq last year. Madigan Army Medical Center officials handled them as second-class soldiers, Guard members told reporters, citing a briefing held by Madigan staff to prepare for the unit’s arrival. It included a PowerPoint presentation that showed a ball cap emblazoned with the words “Weekend Warrior,” and a staff advisory that suggested Guard members might try to game the system to extend their active-duty pay. The soldiers say they didn’t get necessary treatment, and were given the bum’s rush in favor of regular Army troops. The Army said the PowerPoint slide was a poor attempt at humor and denied mistreating the unit, but hasn’t released its final report on the incident. Oregon Sen. Ron Wyden, who is probing the claims, has put a hold on Senate hearings over the nomination of a Deputy Secretary of Defense, a move he hopes will force the Army to release its report.

Adding to the dispute, one of the Guard members, Spc. Nikkolas W. Lookabill, 22, was shot to death by Vancouver (Wash.) police outside his house four months after he was processed at Lewis-McChord. He was killed September 7 after refusing to put down his gun. Family members say he never got the mental-health help he required. A five-page report by the Clark County prosecutor said Lookabill was drunk and agitated that night. Earlier, he’d asked people on the street if they were a “friend or an enemy,” and pointed a gun at one. In a confrontation with police, the report states, Lookabill “told officers that he was a veteran who had fought in Iraq, that he wanted to be a cop, that this was all his girlfriend’s fault, that he wanted them to shoot him.” A standoff ensued until Lookabill went for his .45, and was killed.

A day earlier, Army veteran Robert Quinones, 29, armed with four guns, held three hostages at gunpoint at a Fort Stewart, Ga., hospital, threatening to kill them as well as President Obama and former President Clinton. He pleaded for mental-health treatment, then surrendered. Injured in Iraq and suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, Quinones had recently been medically discharged from Lewis-McChord. His family said he’d been wounded by a roadside bomb, and suffered from depression since his return home. He is now undergoing court-ordered psychiatric help.

Three weeks earlier, Spc. Dustin Knapp, 23, got into a fight with his uncle, stormed out of his Wisconsin home, and was struck and killed by a car as he walked down a two-lane road at 4:30 a.m. His August 16 death, two months after he returned to Lewis-McChord from Afghanistan, was ruled an accident, although there was speculation he’d jumped in front of the car. A member of the same troubled Stryker platoon that spawned the Kill Team, Knapp was distraught, family members said, over the ongoing courts-martial.

“Everyone is an enemy,” Knapp had written on his Facebook page. “I must be my biggest one. All the alcohol I had. All the liquor mixed into one bottle as I’m freaking by myself. I have all my knives open and ready to go through separate arteries and main veins. Who’d miss me anyway?”

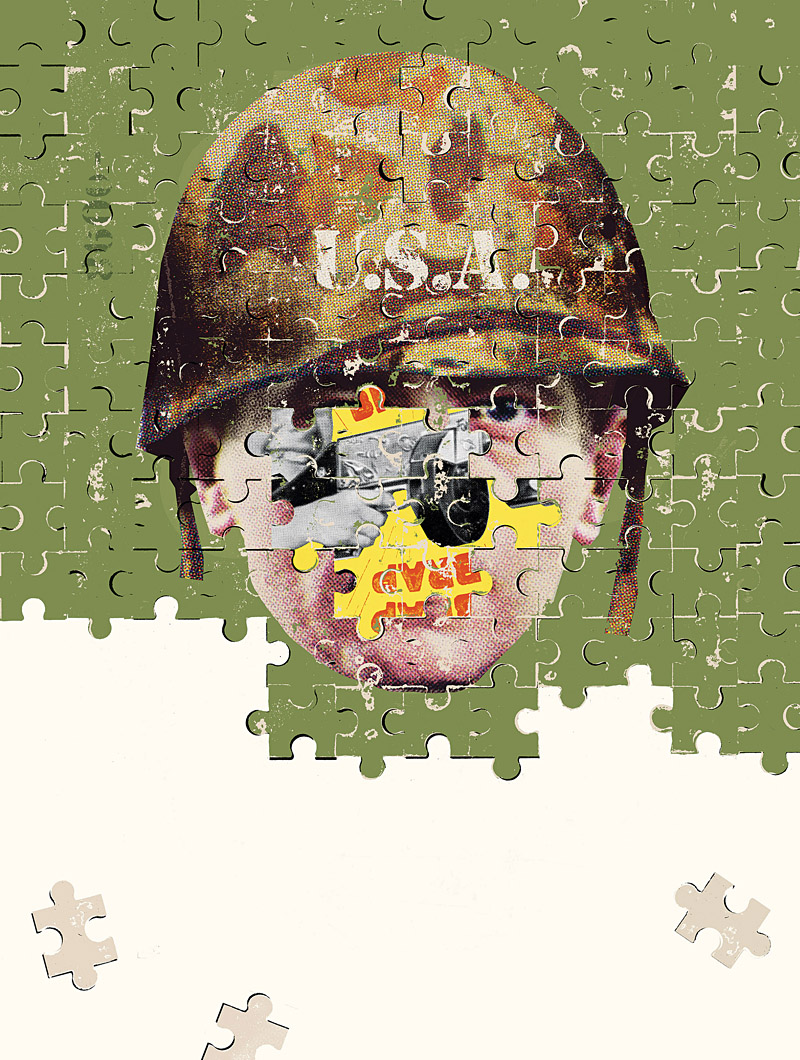

Knapp and the others shared some common demons: the stress of war and post-traumatic stress in peace, aggravated by breakdowns of the military bureaucracy and health-care system. Brandon Barrett’s case, in particular, uniquely illustrates what happens when the Army fails the soldier and the soldier fails himself.

His anger known only to a few other soldiers, Barrett went through his paces at Lewis-McChord, acting as if nothing was amiss after his rebuke and loss of leave time. He performed his duties and promptly showed up for an alcohol assessment at Madigan Army Medical Center on July 15, 2010, according to the Army’s report, from which all names except Barrett’s have been redacted. A doctor recorded his reactions:

“Patient states he was pretty drunk after drinking Jaeger [sic] bombs and beers which began between 8 PM and 10 PM and he stopped between 1 AM and 2 AM and was approached by the MPs around 3:05 AM, with an initial [blood-alcohol count] of 0.164. When this therapist suggested he may have had 15–16 drinks, the patient replied, ‘that sounds about right.’ “

Barrett told the doctor he “likes to drink a lot and just about every day he would drink beer and become drunk.” He had been a heavy drinker since age 18, and before he deployed to Afghanistan drank a six-pack and Jäger bombs four or five times a week. He built a tolerance for booze, he said, which was good, because he could “drink more and make it last throughout the day.”

He was told to enroll in an outpatient program and attend weekly group meetings. Barrett, who also was confined to a limited area of the base, agreed to do whatever they asked. Then, the day after the hospital session, he quietly disappeared. On July 17, he was declared AWOL. Lewis-McChord officials placed at least five calls to his father’s home in Tucson (his parents are divorced), getting no answer. (The Army, it was later discovered, apparently had called the wrong number.) Officials also typed a letter to the family, as required, informing them that Barrett was AWOL. But the letter was never mailed: The Army says one unit thought another unit was sending the notice, and vice versa. Neither did, and the family was never notified.

Barrett, investigators would determine months later in reviewing the case, slipped off the base, bought a 20-year-old Nissan Pathfinder, and arrived at his father’s home in Tucson on July 27. His family was delighted to see him. He didn’t tell them he was AWOL or mention his DUI, according to Army records and interviews. For almost three weeks, Barrett enjoyed special outings, lunches, dinners, and movies with his family. It was one of their most memorable times together, brother Shane recalls.

Barrett had stopped playing video combat games, however. He also told his mother that during his last deployment he didn’t think he’d make it back home. Despite that rosy post-deployment report on his mental-health status, he admitted to his family that he might need some counseling. But, he said, he couldn’t reach out for the Army’s help for fear of being labeled weak, or a nutcase. “Brandon,” says Shane, “was afraid that being labeled would jeopardize his Army career.”

The family commiserated, but felt it would all work out. After all, Brandon seemed in good spirits. “He was looking forward to being transferred to Fort Hood at the end of the year,” says Shane, “which would put him closer to his family.” Everyone commented on how Brandon had grown up. “The Army,” says Shane, “was good for him.”

In fact, it was the other way around. But Brandon never let his family know how bad Army life had become. He was telling others, however.

On August 18, his third week home, Barrett chatted with a friend on his MySpace page—where Barrett listed Nirvana and Pabst Blue Ribbon among his favorites. The friend, a soldier from his unit who was aware Barrett was AWOL (and called him by a nickname, Beezy), asked if he was still in Arizona.

Barrett: Yeah for now. I leave sunday morning for utah

Soldier: You coming backt? to the unit I mean

Barrett: No I got big plans going to make a name for myself.

Soldier: What are you up to? You aren’t going to [do] anything crazy . . . Right?

Barrett: Just watch the news on the night of the 26th.

Soldier: Bud unless you plan on showing your naked ass on tv . . . it isn’t worth it man, we all want you back.

Barrett: I cant come back. If I do Im weak. Its flight or flee.

Soldier: Fight what beezy nobody wants to see you get hurt. Your our brother.

Barrett: I love you guys but sometimes you just have to let go of things you love.

Soldier: You don’t need to let go of us. we are family. let me help you.

Barrett: My mind was made up a long time ago.

Soldier: Beezy are you going to hurt someone?

Barrett: I got to get ready to go out right now, but ill hit you up later/

Soldier: Keep in touch brother just think about what I said. We all want you back/

Concerned by Barrett’s tone and aware he had the date and place for what could be a tragic event, the soldier notified one of his Stryker superiors at Company C, 4th Battalion, 23rd Infantry Regiment. He didn’t want to overreact, the soldier said. But two of Brandon’s comments—”make a name for myself” and “watch the news”—seemed to mimic the stated motivations of the Columbine shooters. That kind of thinking was really out of character for Barrett, the soldier would later tell investigators.

The next day, August 19, Lewis-McChord officials finally began to move. They asked Tucson police to check on the AWOL Barrett at his father’s home. He wasn’t around—a text to a friend revealed that he saw the cops coming and bailed out the back door—but his family learned for the first time that Brandon was in trouble. A fellow Tucson police officer also contacted Shane, asking about Brandon’s DUI, his AWOL status, and some threatening messages he’d sent.

It was all shocking news to Shane, who wondered why the Army delayed contacting the family and hadn’t put out an AWOL notification as required. Police could visit the Barrett home and talk to the family, Shane says, but had no authority to detain Brandon. The Army could have sent MPs from Fort Huachuca, south of Tucson, to detain him. “There is also an Army Reserve Unit near my father’s house,” says Shane. But no MPs showed.

Late that day, the Army issued a bulletin to law enforcement, announcing for the first time—30 days after Barrett’s departure from Lewis-McChord—that the soldier was not only AWOL, but officially a deserter. The bulletin, which included Barrett’s picture, stated “he was ready to fight rather than flee and ready to make a name for himself.” But by that time, Barrett had returned home after his father left, gathered his guns, ammo, and equipment, and drove off to parts unknown.

Other unit members began to hear from Barrett via text and cell. He told some he was planning to return to Lewis-McChord and accept his fate; to others, he said he was just kidding if it sounded like he would hurt anyone. Those may have been attempts to throw pursuers off his trail: He had texted or told other buddies that he had his weapons and body armor with him, and said he’d sooner die than allow anyone to arrest him or put him in jail.

Aware authorities were after him now, he seemed to purposely send mixed signals. “I’ll be in Lewis on Friday,” the 27th, he texted one buddy. But he would be in Salt Lake City, Utah, instead.

Barrett drove his Pathfinder into the garage of the 24-story Grand America Hotel, a prominent symbol of luxury in Salt Lake City’s skyline, around 3:30 p.m. on August 27, a day later than he had planned. As security cameras rolled, he got out and began assembling his military gear. Then he plodded off, rifle in hand, toward an elevator. In a camouflage Army combat uniform and full body armor, bearing a modular communications helmet, an AR-15 rifle, two handguns, and a vest decorated with 21 fully loaded magazines (altogether nearly 1,000 rounds of ammunition, some of them armor-piercing), Army Spc. Brandon S. Barrett was ready for war.

But who was the enemy? It was the question asked by fellow Lewis-McChord soldiers Nikkolas Lookabill, who’d be killed by police 11 days later, and Dustin Knapp, who had died 11 days earlier. It had been hard enough to answer in war zones, where any seemingly friendly civilian can suddenly turn into a suicidal bomber. That happened twice to Barrett’s 5th Stryker squad in Afghanistan.

“During Brandon’s very first foot patrol,” says Shane Barrett, “a suicide bomber attacked his platoon’s formation, injuring 15 soldiers. A third of the wounded were evacuated from the country for medical treatment, One of the wounded was Brandon’s platoon commander. A fellow soldier commented that Brandon felt guilty about the attack. Brandon felt that he ‘could have or should have stopped it.’ Our family believes the incident during his foot patrol and the incident with his senior officer [singling him out and canceling his leave] were the catalysts to the event in Salt Lake City.”

Of course, members of the renegade Stryker Kill Team seemed to have resolved the friend-or-foe identity problem by shooting civilians whether they were a threat or not. But a Stryker soldier in Afghanistan had good reason to be confused: Their commander, Col. Harry D. Tunnell IV, created a “dysfunctional” climate for war, says sociologist Stjepan Meštrovic, a war-crimes expert. He has testified on behalf of soldiers accused of prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib, and provided expert testimony last month at the court-martial of Morlock, the first Kill Team member to plead guilty.

Though U.S. policy in Afghanistan was to win through a counterinsurgency that protected the government and noncombatants, Tunnell, Meštrovic says, took a more aggressive, guerrilla-warfare approach, unconcerned about winning Afghan trust (the brigade’s motto was “Strike and Destroy”). That made the Stryker brigade a “lone duck” among other units, says Meštrovic. He notes that alleged Kill Team ringleader Gibbs had been a member of Tunnell’s own security detail before he was assigned to lead Morlock and the other accused. “There seems to be connections between direct proximity to Col. Tunnell and the chaos that pursued,” says Meštrovic. “Several [brigade members] mentioned the fact that you were good in Col. Tunnell’s eyes if you were aggressive and the body count was high.”

Meštrovic, who has read a confidential 500-page Army report on the brigade (it was released only to some Kill Team attorneys seeking to aid in their clients’ defense), says two generals cited in the report regretted not removing Tunnell as commander before the unit departed for Afghanistan. The brigade itself did not seem prepared to fight, and nearly failed to get approval to be deployed, adds Meštrovic, referring to information contained in the confidential report.

The 3,800-member 5th brigade returned home last May, where it was inactivated and reflagged as the 2nd Stryker brigade. Tunnell, now at Fort Knox, did not respond to a request for comment. In a farewell to his unit last September, according to a report in the Fort Lewis Ranger, Tunnell told the troops, “Our casualties at first were due to the fact we went into places that had not seen large formation of [American soldiers], places that were infested with Taliban.” His methods eventually allowed U.S. forces to gain the upper hand, he said. “What I hope the citizens of the United States will remember about us is that . . . we lived up to our commitment to the American people by honorably performing our duty in combat.”

But Tunnell’s approach caused confusion, mistrust, and uncertainty among the ranks, adds Meštrovic. Or as Morlock put it before he was sentenced on March 23, “I realize now I wasn’t fully prepared for the reality of war . . . I lived in fear of being killed by them [the enemy] every day.”

Brandon Barrett, as he’d later tell his mother, had felt that way too. Now, inside the garage of the Grand America in downtown Salt Lake City, two months after his tour of Afghan combat, he still seemed confused about who might be friendly. He stood by the elevator door, looking around, appearing uncertain about what to do next.

That’s when hotel security officer Robyn Salmon passed by, started to go through a nearby door, then stopped. The sight of a fully armed soldier in her garage spooked her. She came back. Her conversation with Barrett, she tells Seattle Weekly, went as follows:

Salmon: Excuse me, sir, can I help you?

Barrett: I need to go up.

Salmon: To what floor? I’m with security. I can assist you.

Barrett: Just up.

Salmon: Are you on assignment? I need to know what floor you’re going to.

Barrett: Where is the stairwell?

Salmon: I’m sorry, sir, we don’t have a stairwell here.

Barrett: OK then, you better call the police.

Salmon: OK then, follow me out.

To Salmon’s surprise, he did. The 60-year-old daughter of a former Salt Lake City assistant police chief thinks it was her grandmotherly presence that got him to come with her.

“He wasn’t threatening, but he was determined,” she recalls. “I certainly didn’t want him up in our tower with a gun. But I still wasn’t sure if he was on some assignment, part of some Army event or something.”

Outside the garage, where she had phone reception, Salmon dialed 911, half-thinking the soldier might want to talk to an officer. But Barrett strolled onward, heading out toward daylight. “I said, ‘Sir?’ But he continued walking.”

Hotel security cameras focused on what Barrett did next: pace back and forth in a large parking lot bordered by a hedgerow and plants next to a traffic-filled street. It’s a warm, cloudy afternoon, and Barrett seems to waddle under the weight of his equipment, the semi-automatic AR-15 slung downward, cradled in his right arm. He checks his watch and walks in and out of a treed area, back along the edge of the parking lot. He seems to have no idea what to do next. A group of people passes by on the other side of the trees, but he pays no attention. He moves back and forth—all this caught on video, almost six minutes of walking, stopping, turning, and walking again. If he indeed had planned to take an elevated shooting vantage atop the hotel—his equipment pack included a rifle scope and a bipod gun mount—that no longer seems operative. Perhaps he heard Salmon calling the police.

A Salt Lake City police officer with the memorable name of Uppsen Downes was first on the scene, swinging into the parking-lot driveway and spotting the hard-to-miss G.I. Joe raising his rifle in the far corner. As Downes stepped out of his car about 75 feet from Barrett, the soldier immediately crouched in a defensive position, utilizing the hedgerow for cover—techniques he might have used in Afghanistan. Downes started to shout for the soldier to drop his weapon, but before the cop could finish, Barrett opened fire. He clicked off 10 rounds. Most hit Downes’ police cruiser, but one struck the officer in the left leg. A wounded Downes, using his car for cover, doggedly returned fire with his handgun. He managed to get off three shots. One hit Barrett’s most vulnerable spot: his unprotected face. He was dead within seconds.

Security officer Salmon, a civilian employee of the Salt Lake City Police Department for 37 years, says she stood behind a concrete post for most of the shooting, but talked with police about the incident and thinks Barrett was intent on suicide-by-cop. “The soldier was trained to shoot, but his first shot [at the officer] missed low,” she says. “I think that was intentional,” forcing Downes to return fire.

In Barrett’s vehicle, police later found a note scribbled on an Army-issued notebook, according to Barrett’s brother. It read: “You can’t take a man away from his family. Lessons must be learned from this event.” It didn’t make much sense at the time, and the name Barrett made for himself was likely not what he had in mind: Army deserter shot by police. But, as promised, he made the news that night.

Though Army investigators, in their extensive report on Barrett’s death, were unable to determine whether he had planned to kill others, there shouldn’t have been much doubt about his own fate. As he texted one friend a day before the shootout, “It’s almost over—36 hours from now I’ll be dead. I’ve got one hell of an argument and about 1,000 rounds to prove my point.”

At a press conference, Salt Lake City Police Chief Chris Burbank said he was relieved that “In this particular circumstance, [Barrett] had opportunity to engage civilian targets and chose not to for some reason.” But the chief was upset that the Army had never notified him that Barrett was headed his way. “I didn’t come here to point a finger at the military and say ‘You should have,’ because it’s always a challenge with intelligence,” Burbank said. “But in this case, would we like to have had information sooner? Absolutely.”

The Army acknowledges in its report that leadership failed to notify Barrett’s family of his AWOL status in a timely manner. Leadership also “did not facilitate the apprehension” of Barrett when it could have in Tucson. In fact, its whole approach to coordinating apprehension of a deserter was “flawed,” the Army concedes.

Yet the report avoids pointing out that the Army’s delays and errors could have led to the deaths of innocent citizens. As security guard Salmon tells us, “I think I deterred him from going up and shooting people from the tower. He clearly was headed there.” Though Barrett admittedly “experienced significant losses in combat that affected his behavior and actions leading up to the incident,” the Army says, he was not considered at-risk based on his health assessments. Nobody therefore should have expected this. “During my investigation,” summed up the Army’s chief investigator, “I found that the Company chain of command did all that was reasonably possible to save SPC Brandon S. Barrett.”

More than a few of Barrett’s fellow soldiers, interviewed by investigators, disagreed strongly. Some felt the Army wasn’t listening to them, and several complained to officers about the way the DUI had been brought up in formation. “I think had the DUI been handled more privately, there is a chance Brandon wouldn’t have gone AWOL,” said one. “He had said he was humiliated and felt like a total ‘dirt bag.’ ” Another said he had asked an officer to reduce the cancelled leave time, but was rebuffed. Of the Army’s procedures, one said “I cannot understand why he was not more aggressively pursued.”

Brandon’s detective brother says the outcome might have changed had the Army, for one thing, made an effort to find the correct phone number to contact Brandon’s father. Also, having someone double-check to see if the AWOL notice actually had gone out, and sending the desertion notice in a more timely manner, would have helped. As a federal warrant, the desertion notice could have enabled Tucson police to obtain Brandon’s cell-phone number and track his movements.

“The Army says they never knew where he was,” says Shane. “But they paid him. While he was AWOL, he got an Army paycheck at home in Tucson.”

The Barretts will probably never know why Brandon picked Salt Lake City. Shane has since gone there to look around and meet the man who killed his brother, officer Downes. “We shook hands. I wanted him to know that he did what he had to do under the circumstances.” Shane also met with security officer Salmon, handing her a letter from Brandon’s mother in appreciation of Salmon’s help and possible prevention of a worse tragedy. “She called me his angel,” says Salmon.

Shane, who says his brother never gave their family a hint of his suicidal—if not homicidal—plan, has reassessed his impression of Brandon’s happy mood while home on leave. “Looking back on it now, Brandon was making peace with his loved ones,” says Shane. “The only thing he held in higher regard than the Army was his family.”

Last September, Brandon Barrett’s family prepared to bury him with military honors. The family didn’t condone his actions, says Shane. They just wanted to honor him for valiantly serving his country. But the Army, so slow to move when he was alive and in trouble, quickly stepped in. Because he had died committing a crime, Spc. Brandon Barrett, who had earned the Combat Infantryman Badge in battle, could not be buried with a military guard in attendance, the Army ruled.

“We were basically told that Brandon disgraced the Army with his actions, and to give him military honors would reflect poorly on the Army,” says Shane.

Brandon Barrett was laid to rest September 28 without Army honors. A handful of aging VFW members pitched in, firing a salute and playing “Taps” at his burial in a veterans cemetery south of Tucson. Besides the 37 soldiers Barrett’s brigade lost in the Afghanistan war, another six have died to date in non-combat incidents, and 239 have been wounded in action. Barrett’s death is not considered part of the war toll. He died in combat on the home front, where body counts aren’t kept.