When Seattle police were called about a shooting on a leafy, back-end street in the upscale neighborhood of Leschi one evening this past July, they arrived to find a grisly scene. An 18-year-old named Aaron Sullivan was slumped in the driver’s seat of an old blue Chevy Caprice, surrounded by blood and what the police described as “cranial matter.” A bullet had come through the shattered rear window.

As police mobilized a SWAT operation to deal with an armed suspect at large, detectives pulled aside the two other people in the car—Sullivan’s girlfriend, Mariah Gill-Erhart, and a second friend, Grayson “Gray” Wessel—for questioning.

What set are you from? What set is Aaron from? Those were some of the first questions out of their mouths, Gill-Erhart recalls. “I kept having to repeat myself,” she says. “We weren’t in a gang. We didn’t have any weapons.” After being shot at, trying to hold her dying boyfriend’s head together, and seeing “everything go so slow and so fast at the same time,” she desperately needed a cigarette. When she started heading to a neighbor’s house to borrow a lighter, a detective barked Get back in the car. I’m not done with you, she says. “They were aggressive. Too aggressive in that situation.”

“We weren’t treated at all like witnesses or friends of the deceased,” says Wessel. “It was more of an interrogation.”

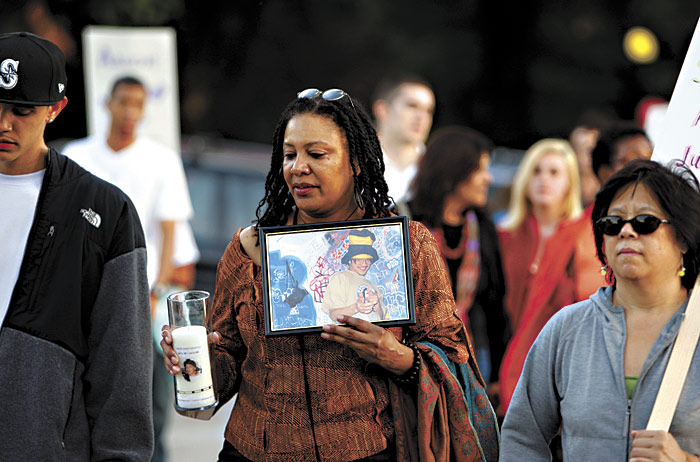

In the murder’s aftermath, law enforcement’s behavior became a heated subject of coversation among Sullivan’s family and friends and members of the city’s African-American community. Sullivan was biracial, and his mother, Debra, is African-American. As dozens of people congregated at Debra Sullivan’s house in the days following the shooting, and at two vigils held on Aaron’s behalf in subsequent weeks, they discussed what they saw as the insulting assumption that Sullivan and his friends were gang members.

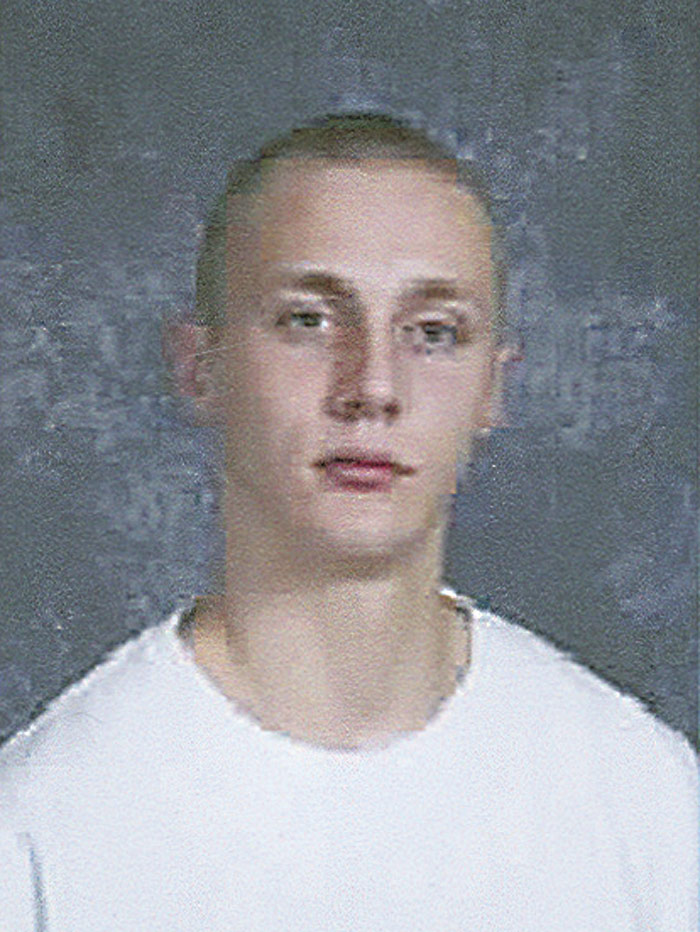

Resentments in the case were fueled by the fact that the murder took place the very same week as the brutal attack on a white female couple in South Park—a crime that received extraordinary public attention. The suspect in that case was a young black man, whose image was widely circulated in the media as police sought—successfully—to apprehend him. He’s been charged with aggravated first-degree murder. In the view of the Sullivan family and others, the murder in Leschi seemed to get a very different reception. For one thing, the image of Sullivan’s alleged murderer—19-year-old Tristan Appleberry, who is white—has never appeared in newspapers or on TV. (Until now: Seattle Weekly obtained his photo from the school district.)

Appleberry was caught the day after the crime. But the judge at his arraignment didn’t allow photographs. Defense attorneys will often argue for the prohibition, saying that photos of the defendant would taint witnesses. The Seattle Medium, a newspaper that serves an African-American audience, ran a story suggesting that in this case the real reason was a “hush campaign by the authorities and the media” with regard to Appleberry’s race. The front-page headline: “Black Youth Killed by White Male.”

Dawn Mason, a Rainier Valley activist, former state legislator, and friend of the Sullivan family, says she has been asking people whether they realize Sullivan’s shooter is white. “Why is that important to know? Because it’s unusual,” she says, and because people would assume otherwise unless told. To some members of the community, publicizing this as a white-on-black case seemed only fair after so many degrading stories about violent African-American men.

“No one [in the media] seemed to treat Aaron with the same degree of attention and respect that’s given to a lot of other shooting victims,” says Tuere Sala, Debra Sullivan’s sister. “But you have articles and articles about some black kid that goes crazy and kills a woman in South Park.” The Sullivan case followed what’s been perceived as a history of scant attention paid by the press to violence against blacks, much of which is not deemed noteworthy because of presumed gang involvement.

“It’s not clear to the general public that this is anything except some drug-related, gang-related, black-on-black thing,” said Sullivan’s mother, in an interview with Seattle Weekly a month after the murder. She was horrified at some of the reader comments posted to news stories about the case, such as one that said the only way to stop gun violence was to “stop living the life.”

“It just brings up all the old issues we have in this country about disparity,” says Harriett Walden, director of Mothers for Police Accountability, a group that monitors law-enforcement abuse. “Black men have always paid the price for harming white people.” In this case, Walden and others say, the white suspect is not paying the price—either in the media or at the hands of the King County Prosecutor’s office, which charged Appleberry with murder in the second degree. “Had it been a case of an African American that had shot a white person,” she says she told King County Prosecutor Dan Satterberg at a forum on public safety, “we believe the charges would have been different.”

A similar insinuation was voiced by Sullivan’s godfather, Garfield High School athletic director Jim Valiere, at a Sept. 10 vigil for the teen and in support of a proposed state assault-weapons ban backed by the family. “As some of you know, the case has not been prosecuted as vigorously as it could have been,” he told the crowd of some 200 people, many of them holding candles, who had marched along Broadway to Volunteer Park.

People who fear that Sullivan will be presumed a stereotype—a troubled young black man who met his demise through his own activities—point to the stature of his family, a sprawling, multiracial clan active in education, the law, and civic affairs.

“These are good kids,” says Mason, referring to Sullivan and his friends, “kids who went to all the right schools and came from all the right families.”

Sullivan’s late father (an Irish American) and grandfather were both well-known lawyers. Debra Sullivan, who holds a Ph.D. in education from Seattle University, is an administrator at Seattle Central Community College and heads the Praxis Institute for Early Childhood Education, a nonprofit that runs teacher-training programs focused on working with low-income students of color. Radiantly gracious and elegant, favoring dangling earrings and long braids, Sullivan has a wide network of friends and professional affiliations, having previously served as dean of Pacific Oaks College Northwest, which trains teachers; as the education director for the Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle; and as a board member of the New School Foundation, which has given money to and helped run two Seattle public schools. Sala has been a city prosecutor for the past 20 years here and in Kansas City, Mo., working most recently in Seattle’s Community Court, which offers jail alternatives to people convicted of low-level misdemeanors.

Ralph Fascitelli, president of Washington CeaseFire, stresses Sullivan’s family background as he discusses his organization’s effort, in concert with the family and other supporters, to use the case to press for an assault-weapons ban in the next legislative session in Olympia. (The measure is named after Aaron.) “We think Aaron Sullivan’s death is a watershed moment,” Fascitelli says, as it shows that guns can lead to violence among even the least likely kids.

Yet interviews with principals at the murder scene and with Sullivan’s friends and family, as well as court and police records, suggest that the case defies easy categorization. The violence has not been tied to gangs, but it was not out of the blue. Threats and allegiances were in play. Nor was it simply black-on-white. Sullivan’s girlfriend is biracial, and Wessel, the third person in the car, is white. And just before Appleberry allegedly shot at the teens, two African-American friends of his, according to the surviving teens, banged on Sullivan’s car. As a whole, the kids were neither Eagle Scouts nor gangbangers but a fluid group that included one person headed to the University of Southern California in the fall (Gill-Erhart) and one headed to jail. Sullivan had many different kinds of friends.

Pictures of Sullivan show a slim, jaunty figure with a mustache and a sly smile. Debra Sullivan and her late husband adopted him as a baby, deliberately looking for a biracial child because they believed such children were often rejected by their parents’ families. He eventually became the middle child of three.

Sullivan describes her son as someone who lived surprisingly “big” for a “not-very-big guy.” From the earliest years, she says, “his projects were everywhere”: an airplane built of parts from a borrowed radio, toaster, and lawnmower; a homemade pool table; a Popsicle-stick mansion. He would ride his bike in the dining room and rollerblade around the rest of the house. In his teen years he loved to cook, whipping up curried prawns or garlic-sautéed clams from shellfish gathered outside the family’s second home at Redondo Beach. One day when he was 16, he decided to have a barbecue for friends while his mother was out. “He went to the neighbors, borrowed a grill, bought charcoal and lighter fluid, and took steaks and shrimp out of the freezer,” his mother says.

“He was a lot of fun,” she says. “It’s just hard to parent someone that fun.”

It became especially hard when his father died of multiple sclerosis. Sullivan was 13, attending eighth grade at St. Therese, a Catholic school in Madrona. He and his father had shared a love of camping, gardening, and fishing. When his father died, Sullivan got “pretty mad,” his mother says. “He refused to go to school.”

His mother sent him for a couple of months to a therapeutic outdoor program for troubled teens in Montana. She says that helped, but upon his return he still struggled, cycling through a series of schools and fighting with her. During one incident in 2006, she says, he tried to barricade her from his room, damaging his door in the process. She called the police. She explains, “My son needed to know: This is not about me and you, honey; society says you don’t get to do that.” According to court records, he pled guilty to one count of “domestic violence malicious mischief” in the third degree, and was sentenced to community supervision.

This past summer seemed to be a turning point for Sullivan, according to his mother. Many of his friends were going off to college and he wanted to go too, preferably somewhere abroad. She suggested that he get his GED and look for a program that suited his interests: engineering, architecture, or culinary arts. In the meantime, he was trying out living in an apartment (although he returned home shortly before his death) and branching out beyond his old St. Therese friends into new circles.

Gill-Erhart, a former participant in the Rainier Scholars program for gifted minority students and now a freshman at USC, reconnected with Sullivan this past summer. She says the two had become friendly in middle school, and stayed in touch after Gill-Erhart left for a California boarding school. Meeting again after her return, they plunged headlong into a relationship. “We’d never be away from each other for more than three hours,” she says.

She describes a tight circle of old and new friends she met through him. One was Wessel, a lanky 18-year-old who had become tight with Sullivan a couple of years prior when they attended high school a couple of blocks apart in the Central District, Sullivan at Nova and Wessel at Garfield. Another was a 19-year-old named Kenny Gross. Gill-Erhart knew Gross as a friendly guy who loved music, but she also understood he was on his way to prison. “I didn’t ask why,” she says. “I didn’t care.” (A look at his court file explains: Gross was then out on bail after having been charged with assault for a drug deal gone bad. He was ultimately convicted.)

Wessel hailed from a tough section of Rainier Beach, and frequently hung out in the Central District. He concedes he has friends who are gang members. “If I’m hanging out with friends who are affiliated, that can be dangerous,” he says. “But then again, I can drop names…and I know nothing’s going to happen to me.” That’s especially true if he’s in the Central District and people see his tattoo bearing the name of Quincy, as in Quincy Coleman, a 15-year-old member of the Valley Hood Piru (according to Wessel and news reports) who was slain last year outside Garfield High.

Given his life experience, Wessel wasn’t especially perturbed on July 22 when talk of violence surfaced. He was spending the afternoon on a friend’s boat at the docks by the BluWater Bistro in Leschi. Someone named Mike was there, and so was Mike’s friend, Tristan Appleberry. Wessel says the muscular Appleberry wasn’t doing much talking, just sitting there with his girlfriend and at one point jumping into the water. Mike, though, was chatting away. He boasted about having and selling guns, including an assault rifle, according to Wessel. Mike also said he had used one of his guns to shoot up Kenny Gross’ car, and planned to do worse to its owner. “Kenny and Mike were beefing because Mike’s ex-girlfriend started going out with Kenny,” Wessel explains.

Wessel excused himself to go to the bathroom, got off the boat, and called Gross to let him know about the threats being made against him. Gross said it wasn’t true about his car and that he was going to “come down there and talk to Mike to get him to stop lying,” Wessel says.

News of the threat was also passed to Sullivan and Gill-Erhart, who headed for the lake. “Basically, we all went down there to back up [Gross],” Gill-Erhart says. “Hopefully, it was just talk.”

When she, Sullivan, and a few other friends got to the docks, they kept a distance from Mike and his friends. Gross hadn’t yet arrived and “it wasn’t our conversation to have,” Gill-Erhart says. But when Mike headed out with Appleberry in a gold van, Gill-Erhart, Sullivan, and their friends followed. They lost sight of the van, but someone knew that Appleberry lived nearby. Divided among three cars, they made their way there.

Appleberry had dropped out of Summit High School in northeast Seattle during his senior year in 2007, according to Seattle Public Schools. His mother was a fixture at the school, volunteering so much that former schoolmate Terrell Shegog says he once thought she worked there. Shegog remembers her son as quiet. “He was like a jock,” Shegog says. “He didn’t seem like a troublemaker at all.”

Because Summit, which the district closed last year, had no football team, its students could play at nearby Nathan Hale. Appleberry did so, along with Shegog. Head football coach Hoover Hopkins was impressed with Appleberry. “I very distinctly remember that he set a pull-up record,” the coach says. Typically, team members can lift their chins over the bar six or seven times, according to Hopkins. Appleberry did it 26 times.

That didn’t help his football career, though; he quit the team a third of the way through the season. The problem, says Hopkins: Appleberry “was not real aggressive…He could do all the physical parts except the hitting part. He didn’t like that.”

There was trouble elsewhere. In 2006, Appleberry was cited by police for negligent driving after weaving across lanes on I-5 late at night and telling police, according to their report, that he had “smoked a bowl.” In 2008, he was stopped by police again and charged with possession of marijuana and driving without a seat belt. In a letter to the court, his attorney submitted a reason for the latter offense: Appleberry had recently been stabbed and therefore advised by his doctor not to wear one. Medical records included in the letter related that Appleberry had walked into the emergency room being “very elusive about where this happened and the circumstances surrounding this episode. He was at some bar in North Seattle…[and] had an altercation with another person supposedly over a comment that was made about his girlfriend.” He had two wounds, in his backside and in the upper portion of his right leg.

On the night of July 22, Appleberry allegedly turned from victim to attacker. According to Gill-Erhart and Wessel’s account, their group of friends lost sight of the gold van, but parked on 31st Avenue South and sat on the steep steps that adjoin Appleberry’s house and lead to 32nd Avenue South. They were completely unarmed, police confirm. Appleberry’s mother appeared carrying groceries into her house, but Appleberry himself was nowhere to be seen. “We waited 30 more minutes,” Gill-Erhart says, and then they walked back to their car.

Sullivan, Gill-Erhart, and Wessel, riding together, swung past Appleberry’s house once more on their way home. “Look, here’s that guy,” Wessel exclaimed as Appleberry appeared.

“We stop the car for a split second,” Gill-Erhart says, long enough to see that Appleberry had a gun and was shouting at them: “You guys get the fuck away from my house.”

“I duck down,” Gill-Erhart says. “I’m thinking, ‘What is going on? I don’t play with guns.'”

They started to pull away when Appleberry’s friends banged on the passenger-side window. Wessel glanced back at Appleberry. “The gun was pointed and he was looking right at me,” Wessel says. “I moved at the last second. I started to tap Aaron.” Then the shot came barreling through the rear windshield, missing Wessel but hitting Sullivan dead-on.

After police arrived and started to question Wessel and Gill-Erhart, one of the detectives took note of Wessel’s Quincy tattoo. “Is that ‘Little Quincy’?” the cop asked, referring to the slain teen’s nickname. When Wessel answered in the affirmative, he says the detective responded: “OK, if you’re not in a gang, why would you have that?” Wessel answered: “Because we went to the same school, because I knew his brother.”

While the cops were questioning him, Wessel was trying to tell them that he needed help. “I was shaking. I was clearly in shock. Aaron’s blood was all over me and I couldn’t hear out of my [right ] ear.” He says he also had glass lodged in his cheek, arm, and thigh. “I asked for medical attention three or four times, and Mariah asked for me.” The teens say police ignored them. Wessel later filed a complaint on the matter with SPD’s Office of Professional Accountability.

Police confirm the complaint, but say they cannot release it or discuss what occurred. SPD was not willing to discuss the case overall in detail, although they responded to specific questions and released a statement that outlined some of the facts.

Eventually, Wessel’s parents came to pick him up at the scene. They drove Wessel and Gill-Erhart to Harborview Medical Center, where police had said Sullivan would be brought.

Wessel says he tried to get into the emergency room to be seen. But hospital security guards and police officers stationed at the door told him no one could come in. “My mom said ‘No, no, no, he needs care.'” They finally let them in, he says, but then a security guard inside started yelling at him. At that point they left for Swedish Medical Center, where doctors tended to his wounds and found no damage to his eardrum. Harborview declined to make anyone available to discuss the events of that night, but a spokesperson said “No patients seeking treatment were denied care.”

According to state Department of Health spokesperson Gordon MacCracken, federal law requires hospitals to see, assess, and stabilize people seeking medical help. “The security issue can’t get in the way of the medical issue,” he says.

Debra Sullivan learned of the shooting from her older son Porter, not from the cops. When she got to Harborview, she says, there were over a dozen kids out front, “all crying, all hysterical—black kids, white kids.” She remembers about a half-dozen security officials were guarding the entrance. “All of this left the impression that this had to be about drugs, it had to be about gangs.”

Like most people there that evening, she didn’t know her son was already dead. “I kept saying: ‘Where’s my son?'”

The officers’ reply, she says: Could you step over here, ma’am? As soon as we have more information, we’ll let you know.

“That went on for an hour. Finally, [an officer] took us over to this little family room [inside the hospital]. He said, ‘I’m going to make this quick. Your son was shot tonight and he’s dead.'”

That was it. No condolences, no explanation about what happened, no offer of support other than calling a hospital chaplain, whom Sullivan says she was too upset to talk to.

All the time Aaron Sullivan’s friends and family had been standing outside Harborview, most of them thinking that he was inside “fighting for his life,” as his mother puts it, the teen had been dead.

Sullivan’s friends and family left Harborview and regathered at Debra Sullivan’s house in south Seattle. Everyone was now wondering where the body was. Sala, the city prosecutor, called the morgue, run by the King County Examiner. It didn’t have the body, telling her to try the hospital again. She did, and the body still wasn’t there. Three and a half hours had now passed since the murder.

“I’m freaking out,” Sala recalls. “How is this possible?”

She called back the morgue, where, she says, a staffer finally told her how it works: A body stays at a murder scene until police release it, and that hadn’t happened yet. “You mean Aaron is lying in the street somewhere?” she says she thought. The idea filled her with a “visceral panic”—and “rage.” In her long professional experience with police, Sala says she had viewed them as protectors. But this didn’t seem like protecting Sullivan, even if he was already dead; this seemed like “tossing him to the side.” Remembering that moment, she says: “I totally understand why we have all this retaliation. It’s an emotional whirlwind.”

For the first time, Sala says, she was seeing law enforcement from the perspective of a victim, and a lot of things didn’t square with her prosecutorial mind’s way of seeing things: the police’s failure to get medical aid for teens who had been shot at, the way the cops appeared to view Sullivan’s family and friends outside Harborview “like criminals,” and the unfeeling way her sister was informed of Sullivan’s death. “Police had to have an opinion about Debra and Aaron to treat her that way,” she says.

At about 2:30 a.m., the Sullivan house finally received a call from the King County Examiner to say that Sullivan’s body was on the way there. It arrived at 5:09, according to the county.

In the days that followed, family members said, they were virtually abandoned by police. Detectives didn’t come around to interview Sullivan’s friends, who continued to gather for days at his house, nor did they provide updates on the case. “Is it normal that the victim’s mother wouldn’t know anything?” Debra Sullivan asks.

In a word, yes, according to David Kennedy, director of the Center for Crime Prevention and Control at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City. “Police agencies generally conduct investigations with the goal of solving the crime and preventing future violence”—and without much consideration of victims’ wants or needs, he says. “You can be informed of next to nothing about the progress of the case. It is a chronic complaint of victims.”

SPD does employ two “victim advocates” inside its violent-crime department whose job is to “serve as a resource for victims and help them through the court process,” according to police spokesperson Sean Whitcomb. Many police departments don’t have such personnel, says Fanny Correa, director of Separation and Loss Services at Virginia Mason Medical Center, which offers therapy to families of crime victims. She says SPD’s victim advocates often refer clients to her, and she has seen them in court, sitting by victims’ sides.

Debra Sullivan, however, says she didn’t get a letter from an advocate until a week after her son’s death. A lot of resentment had built up by that time. The family did get a visit the day after the murder from Jamila Taylor, who runs a new “street outreach program” that works with youth affected by violence and aims to de-escalate passions that could lead to retribution. Funded by the city as part of Mayor Greg Nickels’ Youth Violence Prevention Initiative, it receives cooperation from the police department, which quickly lets Taylor know when violent incidents occur. Taylor, who had a voice mail from police waiting for her at 6 a.m. on July 23 when she woke up, helped plan the first vigil for Sullivan a week after his murder and attended the second. Family members lauded her efforts.

Taylor stresses her team’s independence—”We’re not an agency of the police department,” she says—so the family apparently didn’t realize that police were in any way involved with her work.

In a meeting with homicide brass in early September at Debra Sullivan’s home, the family learned other facts about the case. They found out, for instance, that while police hadn’t come around to interview potential witnesses in the days following the murder, the cops had gotten lengthy taped statements from Gill-Erhart and Wessel at the scene. Sullivan’s friends had complained that the cops had been so rude that they didn’t listen to what they had to say about the crime, but police told the Sullivan family at the meeting that it’s not unusual for traumatized witnesses to forget all the information they convey. John Jay’s Kennedy agrees. “In that situation your memory is not accurate, you have tunnel vision, you forget what you say and who you say it to.”

The information about their investigation that police shared at this meeting convinced the Sullivan family that cops were not blowing off the case. Sala, who was there, says: “By the time we left, we got the impression they took this real serious.”

Another issue discussed at the meeting was the treatment of Sullivan’s body. According to official policy, the Medical Examiner’s office doesn’t transport victims’ bodies back to the morgue until police collect the forensic evidence they need from it and give their authorization to move it. Typically for homicides, this takes several hours, according to James Apa, spokesperson for Public Health—Seattle & King County. In the South Park case, it took only an hour and a half.

But in this case, police had something else on their plate: a massive SWAT deployment. Police closed off the block as dozens of officers arrived, including snipers who took up strategic positions around neighboring properties. They shot out the windows of the Appleberry home and, according to interviews with neighbors, blared on their bullhorns: “Tristan, come out!”

Neighbors debated for weeks afterward whether the police response was excessive, especially since Appleberry’s mother, who emerged, claimed that her son had already left. (He was found in West Seattle with his girlfriend the next day.) “I felt it was a huge, paranoid operation,” says one neighbor, pacing his kitchen and declining to be identified. Debra Sullivan doesn’t fault police for this, though, allowing that police couldn’t have known whether Appleberry was there or not.

“I was so mad at the police before and now I’m so not,” she says in a recent interview.

Still, she says, that doesn’t mean that everything that happened was right—for instance, the way she was told about her son’s death. The family says that police apologized at the September meeting. “They were visibly very upset that it happened that way,” Sala says. Even so, it’s still unclear whether police were responsible for giving the news. In interviews, SPD spokesperson Whitcomb initially denied that was the case, saying that it must have been a hospital security guard. Harborview replied that it had “no knowledge” of that. Later, Whitcomb said that it might have been a police officer after all: “We just don’t know.”

Unlike in many jurisdictions around the country, police here are not expected to deliver death notifications, the Medical Examiner is—protocol delayed in this case by the SWAT action.

Sullivan also remains concerned over what she calls “an automatic assumption that a child of African-American descent is involved in gangs.” Whitcomb agrees that “moments after the shooting, everyone was open to the possibility that there might be some gang nexus. It was youth, homicidal violence involving a gun.” SPD will not say whether it still considers gang involvement a possibility.

Police experts locally and nationally maintain that questions of gang involvement would be natural and reasonable in a situation like this. While stressing he did not know the details of this case, Kennedy, who has become a guru in the war on teen crime, and who recently visited Seattle to confer with police on a new deterrence program in the Central District modeled on his ideas, points out that “groups of young men involved in gun violence are deeply, disproportionately gang members.” In some cities where his center has done field work, he says, 50 to 75 percent of such shootings are gang related. Throw in an assault rifle and some kind of ongoing beef, he says, and “it’s a situation that screams gang involvement.”

“That doesn’t mean it’s true,” Kennedy adds. “But you find out.” And when you “ask someone ‘Are you a gang member?’ and they say no, you ask again.” One reason it’s important to find out immediately is to prevent likely retaliation, which he notes is increasingly occurring outside hospitals where shooting victims are brought. “This has become a major issue,” he says, and many hospitals respond, as did Harborview, by restricting access.

Kennedy continues: “A good police department also knows that [questioning about gang affiliations] is an incendiary issue, and that if you get it wrong…people will be offended.”

Lisa Daugaard, deputy director of the public-defense attorney group called The Defender Association, adds that being taken for a criminal can be particularly humiliating if one is actually a victim or someone close to a victim. This doesn’t just happen in the context of gang suspicions. She recalls a case some years back in which police responded to a domestic-violence call and assumed that the man who opened the door was the attacker. In fact, he was another member of the household who was trying to protect the woman under attack. “Yet he was ordered to the floor and got the foot put in his back.” She says police also ended up restraining the victim who tried to defend him, and then her 7- or 8-year-old son who tried to defend his mom, before realizing that the real perpetrator was escaping out the back door.

As for the charges, Ian Goodhew, the King County Prosecutor’s deputy chief of staff, says both first- and second-degree murder require “intent” to kill. But first-degree murder also demands “premeditation,” defined by law as an idea that takes form in someone’s head for “more than a moment.” In the South Park case, he notes, the attacker let the notion sit for an hour and a half as he held a knife to his two victims, raped them, and repeatedly suggested that they would not be around later to tell police what happened.

In the Appleberry case, Goodhew says: “What evidence of premeditation did we have? We had none.” He notes that the murder wasn’t the result of an argument between Appleberry and Sullivan—which, one might deduce, could have led Appleberry to plot revenge, thus meeting the legal standard of premeditation—but between their friends.

Critics like Dawn Mason point to the fact that it took more than a moment for Appleberry to get his gun, walk outside, and shoot Sullivan. But Goodhew says “you need evidence of what was inside his head. Was it: ‘I’m afraid these guys are going to beat me and my mom up?'”

The notion that Appleberry might credibly claim self-defense rubs Sala the wrong way. “I do think that it’s a lot easier to swallow that a white kid might be scared of a black kid than a black kid would be scared of a white kid,” she says.

The Appleberry family could not be reached for comment, and Tristan’s lawyer did not return phone calls.

Asked what he thought was in Appleberry’s head, Wessel says this: “I honestly think maybe Tristan felt a little bit threatened by us.” But “not enough” to warrant doing what he did, Wessel adds, saying the only conclusion he can come to is that “Tristan is insane.” It’s but one more assumption in the case.