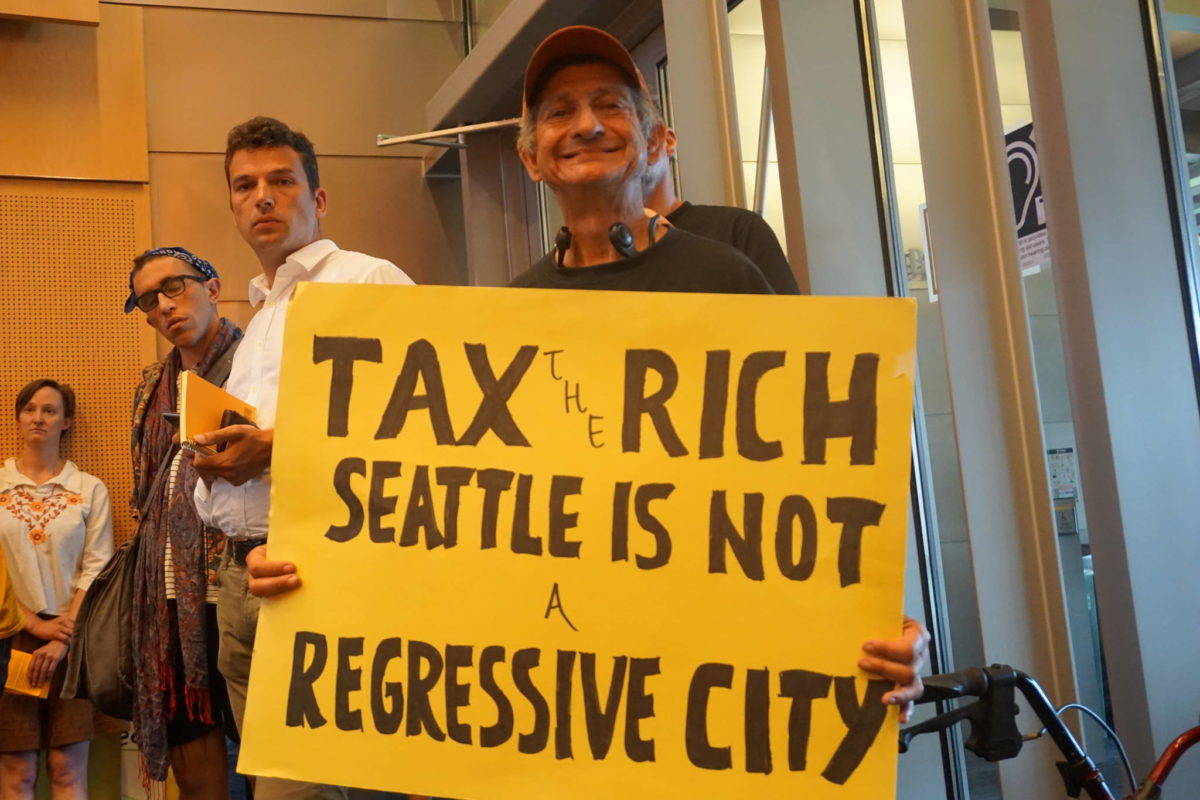

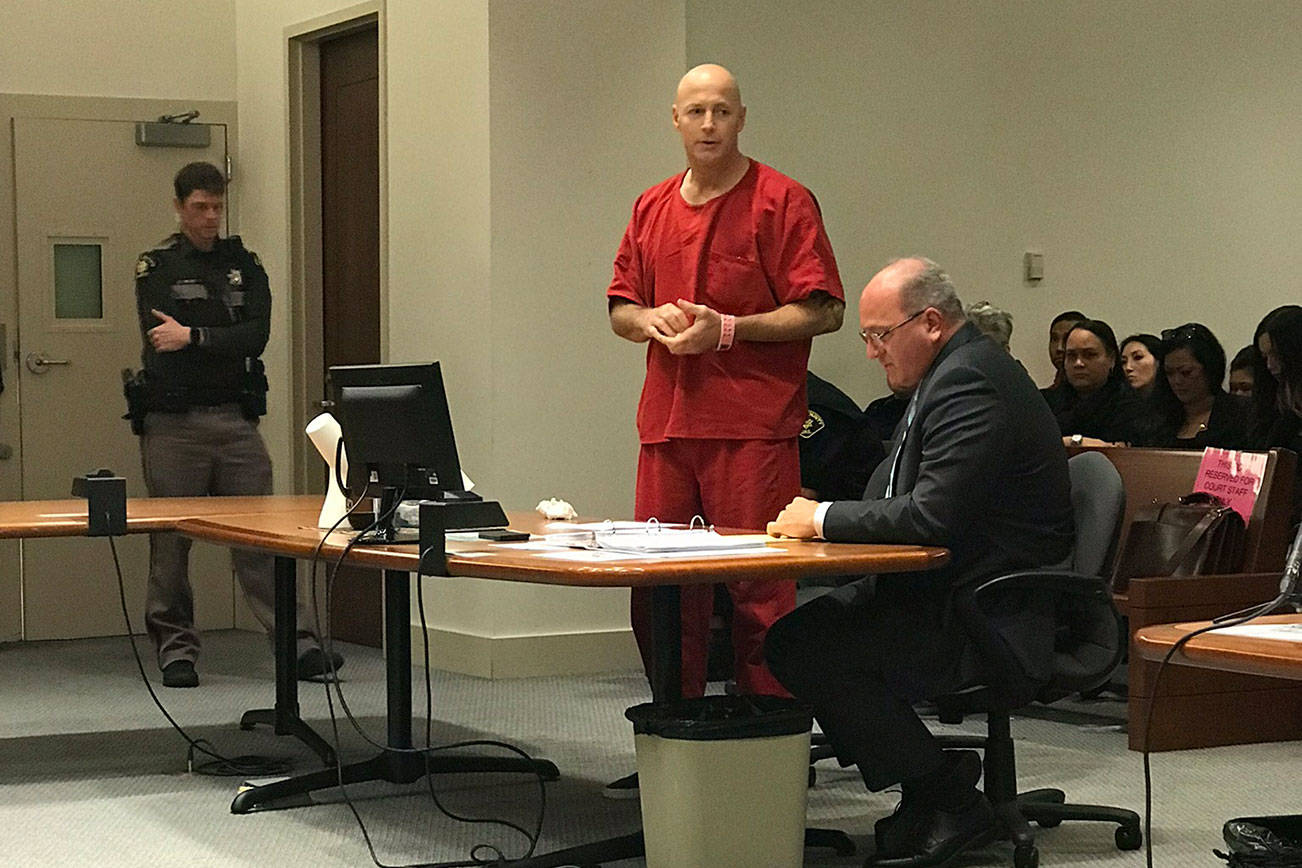

On Friday, a King County Superior Court judge will hear arguments on the legality of the income tax proposal approved by the Seattle City Council over the summer. The hearing is the first step in litigating the lawsuits filed against the City of Seattle that, if successful, could scuttle the attempts by activists and city leaders to introduce a more progressive tax structure.

The council’s ordinance, which would levy a 2.25 percent tax on individual incomes of more than $250,000 and household incomes of more than $500,000 and raise an estimated $140 million annually, garnered a rapid-fire filing of lawsuits to oppose its implementation; by August 30, a total of four lawsuits were filed by various Seattle residents—including local conservative businesswoman Faye Garneau.

The frenzied legal backlash was expected and is actually part of the plan. The Seattle City Council passed the income tax ordinance with the explicit intent of taking the matter to court. In a statement made shortly after the council unanimously approved the ordinance, then-Mayor Ed Murray said that Seattle was “challenging this state’s antiquated and unsustainable tax structure by passing a progressive income tax.” The city budgeted $250,000 to hire outside counsel to assist in the litigation process.

The complaints largely center on the same legal arguments: that the tax violates a state statute that bans local governments from levying taxes on “net income,” that Washington state Supreme Court rulings from the 1930’s deemed income taxes as unconstitutional, and that Seattle lacks explicit permission from both state statutes and the City Charter to enact an income tax.

With the legal briefs typed up and arguments solidified, Seattle Weekly checked in with attorneys representing both the defendant and the plaintiffs to get a preview of what’s to come.

“We’re feeling good,” said Scott Edwards, an attorney from the Lane Powell law firm and lead counsel in the lawsuit representing Garneau (along with 19 other plaintiffs). “This is an unusual case because the City Council enacted a tax that they knew to be illegal so we expect the court to recognize the illegality of the tax after next Friday’s hearing. Cities don’t have plenary taxing authority; they only have whatever taxing authority the state legislature has granted to them. The city’s statutory authority to license for revenue does not extend to income tax. The tax is not authorized by the statutes that authorize cities to tax and to the contrary, it’s expressed prohibited by statute.

“We believe that those arguments should be dispositive of the case,” Edwards added.

In the City of Seattle’s corner is Paul Lawrence, an attorney with Pacifica Law Group; Hugh Spitzer, a professor of law at the University of Washington; and in-house staff from the City’s Law Department.

“The overarching theme [of our argument] is that this is a tax that the city is authorized to impose,” Lawrence told Seattle Weekly.

This, said Lawrence, is because the ordinance taxes gross income and not net income (which is the type of income explicitly banned by state statutes). “We distinguish between what I as an individual resident take in versus what the entity I work for earns,” he said. “It looks at it from a personal income basis and we think that, in that context, we have a gross income tax and not a net income tax.”

Naturally, Edwards disagrees. “It’s a fictitious argument that they concocted to avoid a statute that clearly prohibits what they did,” he said.

Lawrence said the city will also argue that the 1930’s Washington state Supreme Court ruling that income is property and, therefore, must be tasked uniformly (a position which is at odds with the basic premise of a graduated progressive income tax), relied on a faulty interpretation of a U.S. Supreme Court case and was invalidated by Supreme Court rulings in other cases. “The U.S. Supreme Court has consistently rejected the characterization of an income tax as a property tax,” the brief filed by the attorneys representing the City reads, going on to cite Supreme Court cases from 1916 and 1939 to support their claim. Additionally, Lawrence argues that the state Supreme Court of the 1930’s incorrectly stated in their ruling that the majority of states and courts view income as property. “Washington’s treatment of an income tax as a property tax was and remains an outlier,” the brief states.

He added that state statutes grant local governments broad authority to levy taxes of all sorts for local purposes. “When you put all that together, the city does have authority to impose an income tax,” said Lawrence.

Edwards argues that these arguments are largely irrelevant due to prohibitions in state law on income taxes. “None of that matters in the sense that they don’t have statutory authority to do what they did.”

In a preview of the kind of ontological wrangling we can expect from the case, Lawrence contends that the City’s income tax is actually a form of excise tax, which is allowed under state law, and that, more broadly, Seattle has “authority that the state legislature has granted to cities to excise the power to tax for all local purposes.”

This last argument is a new one from the City, and was not included among the arguments in the motion for summary judgement filed by the Seattle City Attorney’s office back in early October. Lawrence cites a specific statute that grants “code cities” (which is the classification of most Washington cities with their own municipal codes) that gives said cities “all powers of taxation for local purposes.” He then points to a related state law that extends this authority to all “first class charter cities” (i.e. cities with populations of more than 10,000 that have adopted city charters—like Seattle).

The King County Superior Court judge hearing the case, John R. Ruhl, will likely take a few weeks before issuing a ruling after Friday’s hearing. From there, regardless of the outcome, the ruling will almost certainly be appealed to the Washington state Supreme Court. “I would say that there is a certainty that it will be appealed,” said Lawrence.

“The bottom line here is that the November 17 hearing is just the first step of a case that will go to the state Supreme Court,” he added.

Edwards criticized the City for using the judiciary to push forward a local ordinance instead of lobbying the state legislature to change the statutes. “If they want to change the law, this is not the right way to go about doing it,” he said. “We live in a democracy. There are proper procedures for getting the law changed; you can go to the legislature, there are statewide referendum; that’s the right mechanism for amending state law. Engaging in an act that is clearly unlawful in order to try to get the court to change the law is simply inappropriate.”

On October 31, Councilmember Lisa Herbold (District 1–West Seattle) introduced an amendment to interim Mayor Tim Burgess’s proposed 2018 budget requesting that the budget office submit a report to the council by March 1, 2018, on possible uses for the revenue from the income tax. Still, the City will wait for the outcome of the four lawsuits before moving ahead with implementing the income tax. Director of the City Budget Office, Ben Noble, told Seattle Weekly that they are also holding off on hiring additional staff to oversee the tax.

Meanwhile, activists in Port Townsend have been pushing for a similar income tax ordinance in the wake of events in Seattle.

news@seattleweekly.com

Correction An earlier version of this story identified Hugh Spitzer as a municipal government attorney at Foster Pepper law firm. He is no longer with the firm.