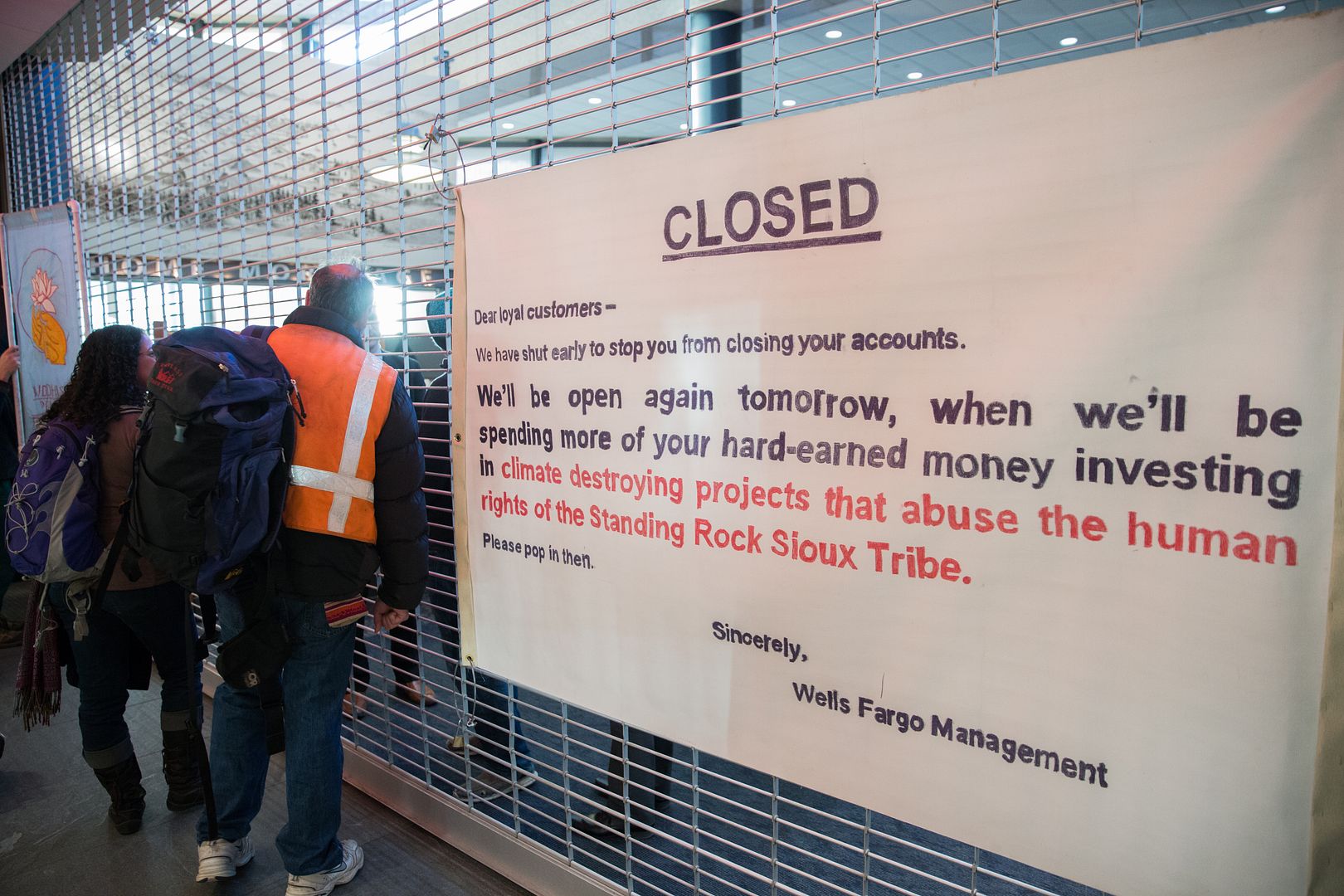

On the crisp afternoon of January 5, hundreds of Seattleites stormed the downtown Wells Fargo Center—shouting, hoisting signs and banners and a large makeshift “R.I.P. DAPL” pipeline, beating drums, tooting horns, and chanting. “Wells Fargo should DIVEST from the Dakota Access Pipeline! Water is life! Water is life! Mni Wiconi!” Inside the bank, a long line of account holders wrapped around the room, gathering en masse to pull their money out of a financial institution that has contributed $467 million in direct financing to the Dakota Access Pipeline.

The Standing Rock Sioux and thousands of activists and citizens of all stripes have been protesting the pipeline for months, and the Department of the Army’s decision on December 4 to deny the project an easement required to drill under Lake Oahe put “a finger on the pause button,” says Seattle-based Lakota activist Matt Remle. That pause has allowed activists to step back from the front lines and concentrate on other ways to help the cause, he says. Namely: Cutting off the money.

“My particular sum of money isn’t going to be the thing that breaks the banks,” laughs Seattle resident Rebecca Deutsch, who closed her Wells Fargo account Thursday. Still, she—like many who feel galvanized by both Standing Rock and the chilling prospects of president-elect Donald Trump—figured that joining in with a whole bunch of people at once “sends a stronger and louder message.” So far, the amount of money that account holders across the nation have moved out of the 17 banks that have directly or indirectly financed the Dakota Access Pipeline amounts to more than $44.5 million.

Photo by Alex Garland

But in the scheme of things, $44.5 million between 17 institutions is not going to break the banks, either. Seattle might deal a far stiffer blow if it passes an ordinance sponsored by Councilmember Kshama Sawant that would end the city’s $3 billion relationship with Wells Fargo by December 31, 2018. Ultimately, though, there’s more to fossil fuel financing than the money in our checking accounts, or even a city’s: The more complex and entrenched aspects of corporate power may lie in the stock market.

The bulk of individual wealth isn’t concentrated in checking accounts, of course. It’s invested in 401(k)s, IRAs, mutual funds, stock portfolios—the money people count on to grow, so it can be there when they retire, or when their kids go to college. And because investing is a rather opaque art to many of us, those portfolios can easily be wrapped up in all sorts of endeavors that their account holders might not agree with—oil pipelines, say, or petrochemicals, or private prisons. And when people decide they want to change that, they may encounter resistance from financial advisors, whose job it is to grow their clients’ wealth.

At a party recently, a friend complained to me about just that: she was a Bernie Sanders delegate last year and, like many irate Seattleites following Trump’s election, feels desperate to do something. She told me she asked her financial advisor what it would take to move her money out of what she now sees as unethical stocks, and he said she could, but it wasn’t a wise choice, if she wanted her portfolio to make money.

That experience isn’t uncommon, say two of the advisors at Natural Investments, LLC, a “sustainable, responsible and impact” (SRI) investment firm with a branch in Seattle. “What people tell us when they find us,” says Ryan Jones-Casey, director of client services, is often something like, “’I’ve heard that I can do socially responsible investing, but I talked to my advisor at JP Morgan, and he said I’m going to lose money; he said it’s not worth my time.’”

Photo by Alex Garland

SRI investing considers a slew of values-based criteria, such as a company’s environmental and human rights track record, as well as its financial performance. There is now a preponderance of evidence to suggest that SRI investing is just as profitable—if not more profitable—than traditional, numbers-only investing strategies. The MSCI KLD 400 Index, similar to the S&P 500, but with social and environmental criteria applied, performs at least on par with, if not better than, the S&P. And study after study—and even a study that analyzed some 2000 different studies—supports the idea that there is no discernible financial difference between socially responsible investing and traditional investing.

So why would an advisor tell a client otherwise? “Fear… and/or inertia,” muses Natural Investments advisor Eric Smith, who has been involved in SRI since 1986. He adds that a conventional financial advisor might also simply not know about the evidence out there; it could be “naivete or ignorance,” too.

The stock market is, arguably, based on belief. The more investors believe that something has value, the more they tend to invest in it; then, in turn, the more value it has. That might be part of what creates inertia: Letting the past predict the future, brokers lean on old patterns and ideas about what makes money on Wall Street. Like, “I don’t want to learn something new; I’ve always done it this way,” says Smith. Not to mention that “a lot of people in the financial services industry tend to be relatively conservative,” he adds, so if some of the political aspects of SRI “[don’t] fit their philosophy, they don’t want their clients to do it.”

Certainly, “fear is a powerful barrier to change” in investing, says Jones-Casey. But he and Smith argue that a company that is resource efficient, watches its carbon footprint, and cares about human rights “is a more enlightened company,” and this kind of enlightenment “is actually the very thing that will lead to better financial performance over the long term. But that kind of thing is not at all the dominant paradigm in the financial services industry.”

Photo by Alex Garland

Not yet, at least. But it does seem to be changing. In the past few years, more and more firms are looking at SRI methods. Today, some $8.72 trillion in U.S.-based assets are managed using socially responsible criteria — one out of every five dollars under professional management in the country, and a 33 percent jump from 2014 — according to a 2016 trends report by the Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment. In December, the amount of money that individuals and institutions across the globe had pledged to divest from fossil fuels topped $5 trillion. And to some SRI-savvy people, conversations with their financial advisors have gotten easier, too.

“I choose to invest in things that I think are life-affirming, and in accordance with my values,” says Sandra, a Seattle resident and environmental activist who sold her software company 15 years ago (she asked that her last name not be used). “In the past, when I first started doing investing, there was a lot more resistance” to SRI, she says. “I have noticed that… [advisors aren’t] raising an eyebrow anymore. Like, ‘You don’t want to invest in GE or Monsanto? I get it.’”

After spending 10 days in late October with the water protectors at Standing Rock, where she was tear gassed and slugged with rubber bullets, Sandra moved nearly $1 million of her assets out of Wells Fargo Advisors, the bank’s wealth management arm. She says she’s maintaining her stocks in wind and solar and other eco-friendly industries—and she’s sure she’ll find another advisor to help manage those. “Not to toot my own horn,” she adds, “but [my portfolio] does really well. Which is excellent. A huge percentage of that income goes straight into the causes that I believe in.”

Deutsch, who says she gave up activism after college, but took it up again after the election, is determined to keep working on the divestment movement long after her Wells Fargo checking account is closed. She wants to keep pressure on the Seattle City Council and other institutions, as well as query her own 401(k), mutual funds, and credit cards. “That gets hairier,” she says. “These things can feel like black boxes.”

But “we all need to start asking more questions of what our money is being used to fund,” she says. Sure, there are “plenty of financial advisors who are falling back on conventional wisdom.” It’s time, she argues, to be “expanding our view of what’s possible.”

sbernard@seattleweekly.com

Correction: An earlier version of this article in one instance misidentified Smith and Jones-Casey as brokers. They are financial advisors.