This week, Seattle took several steps to further the promises made in the police accountability legislation passed in May. First, Mayor Tim Burgess nominated a civilian who will investigate police misconduct; then, the city entered into a tentative agreement with the Seattle Police Management Association (SPMA), one of two police unions. Among other things, the agreement endorses the new legislation and agrees to a trial of body cameras for some high-ranking officers.

The moves come a few weeks after the U.S. Department of Justice announced that the Seattle Police Department has met the requirements of the first phase of a 2012 consent decree, which obligates SPD to improve its relationship with citizens and to reduce its use of excessive force. If federal judge James Robart agrees with the DOJ’s assessment, SPD enters a two-year probation period during which it must demonstrate sustained compliance. After that, it would be free and clear of the consent decree forever.

Yet some Seattle activists who are concerned about biased policing say that a culture of aggression and intimidation within the police department persists—and they doubt that the new legislation will change that.

The police accountability legislation was designed to ensure checks and balances of SPD by creating three police oversight agencies. Those agencies include a civilian-led Office of Professional Accountability (OPA), which is charged with investigating complaints about police misconduct, and an independent auditor of the police called the Office of Inspector General. The legislation also made permanent the Community Police Commission (CPC), which was established under the consent decree. For the legislation to be fully implemented, though, the city needs to enter collective bargaining agreements with both police unions. If both of the unions agree to the legislation in their bargaining agreements, then Judge Robart will give final approval of the ordinance, according to a September written order.

Now that the city has entered into one tentative agreement with the SPMA, which represents SPD lieutenants and captains, the puzzle is nearly complete.

The City Council is expected to act on the agreement next week. Councilmember M. Lorena González has already expressed her approval of the SPMA’s contract. “The road to creating meaningful, and lasting, police reform is not an easy one. There must be more than words, there have to be actions. Today the women and men of the SPMA have taken that action,” González said in a Monday press release. “I deeply respect the work it took to reach this agreement and am grateful to the members of SPMA for ratifying this contract and for getting us one step closer toward full implementation of our police accountability legislation.”

And on Tuesday, Burgess nominated Andrew Myerberg as the director of the OPA. Myerberg has already been serving as the interim director since July. Myerberg was also the lead lawyer in the court case that led to the federal consent decree.

“During his time in the City Attorney’s Office, Andrew served for a time as the lawyer advising the Community Police Commission. We found him to be committed to reform of policing, and also, comfortable with elevating the voices of community leaders and honoring community expertise. These are essential qualities at OPA,” said Isaac Ruiz, CPC Co-Chair, according to a press release. “Since he took over as interim OPA Director, we’ve seen improved practices and a dedication to transforming that agency, as well as improved morale. SPD employees have also expressed confidence in Andrew’s fairness. The CPC looks forward to partnering with Andrew to strengthen community oversight of policing in the years ahead.”

But despite all of the recent steps to increase transparency and accountability, some community activists who focus on racial justice say that the police department’s relationship with the community has only improved on the surface and that the city is far from the kind of transformative change they’d like to see.

Cliff Cawthon, a community activist and political science instructor at a local community college, says that he has seen a concerted effort by police to appear more respectful of marginalized communities by getting out of their cop cars and interacting with citizens. Yet he says he’s seen SPD officers wearing “Blue Lives Matter” iconography on their uniforms, which he considers antithetical to purported gains in their interactions with communities of color.

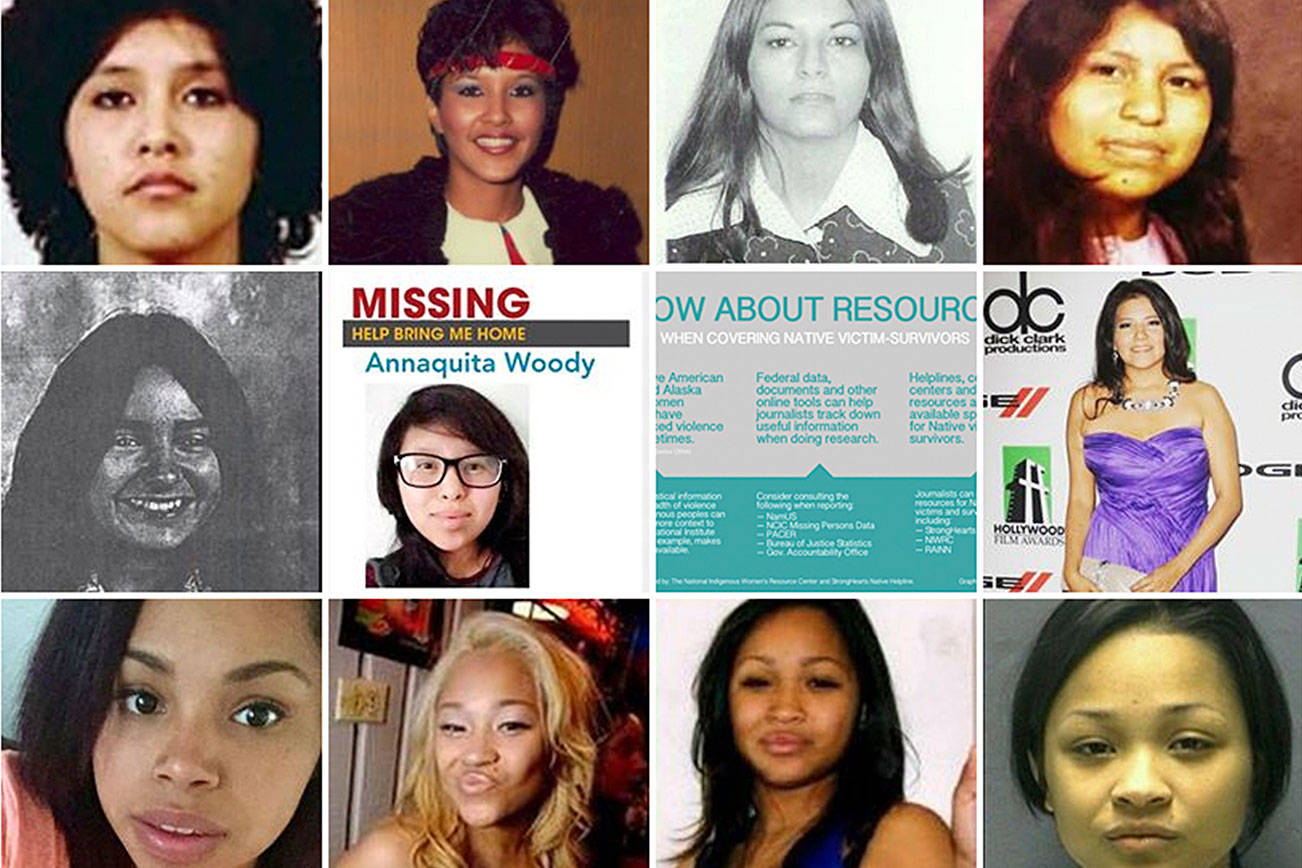

The fatal police shooting of Charleena Lyles in June, he adds, suggests that police officers still employ excessive uses of force on people of color. “It’s way too soon to declare the war won with regards to police brutality,” Cawthon says. “The fact that that tragedy happened in the first place is a testament to the fact that the consent decree … might have been achieved on paper, but in reality, they still have a lot more to do.”

But, he clarifies, he has some hope that Myerberg, as OPA director, could play a positive role in holding SPD accountable “if and only if they [the OPA] remain independent.”

Ed Mayer, an organizer with Got Green, a group that helps empower communities of color and low-income people to join and lead the environmental movement, says that he doesn’t believe that SPD has improved its relationship with communities of color in recent times. He is African American and has three sons in their early 30s; he says when he was teaching them how to drive years ago, he trained them how to not appear threatening in case they got pulled over by police. And today? “I’m still afraid for all of our young brothers.”

In the eyes of many members of communities of color, police brutality has persisted, says KL Shannon, the Police Accountability Chair for the Seattle/King County NAACP. She says any efforts to improve relations were “thrown out the window after the murder of Charleena Lyles and Che Taylor.”

The NAACP still receives “a number of calls” from community members complaining about police brutality, Shannon says, although she’s unsure if the total number of complaints has changed at all since the implementation of the consent decree.

Like Cawthon, she believes that the legislation could go further, and that Myerberg should be completely independent from the police department in order to investigate police actions. “The director should not be reporting to the Chief of Police. I mean, that’s a joke,” Shannon says. As it stands, Myerberg would report his findings to the Chief of Police and SPD sergeants would conduct the investigations. Under the new legislation, the OPA will include both SPD and civilian investigators.

In an email to Seattle Weekly on Friday, SPD wrote that it “continues to work closely with our community and federal partners to ensure constitutional and effective policing in our city. Our Force Investigation procedures were developed under the oversight of the Department of Justice, and we have emphasized the importance of de-escalation and alternatives to use of force in our training.”

The department added that it fully supports the nomination of Myerberg to the permanent position of OPA director, and that as the interim director he has shown a “steady commitment to fairness and transparency.”

“We believe we have shown our department is committed to reform, but we know we still have more work to do,” the email concluded.

Federal court-appointed monitor Merrick Bobb, who is charged with overseeing Seattle police reform, wrote in a September 8 status report that the police department has made gains, but falls short of meeting the consent decree requirements. Bobb told Seattle Weekly that he is on a confidentiality order with Judge Robart and thus cannot discuss his opinion of the DOJ’s belief that Seattle has met the initial requirements.

The Office of Police Accountability did not immediately respond to Seattle Weekly’s requests for comment.

mhellmann@seattleweekly.com