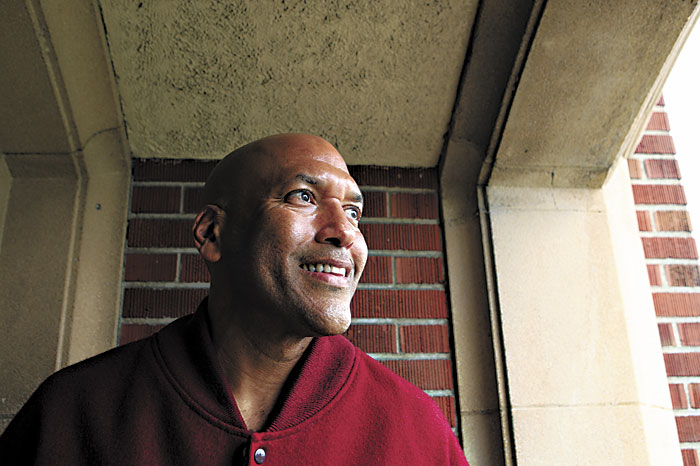

After weeks of speculation, James Donaldson will officially announce his candidacy for mayor of Seattle on March 26. A 7’2″ ex-Seattle SuperSonic and Washington State University Cougar who lives in Magnolia, Donaldson, 51, will spot the incumbent about $200,000 and a lifetime of political experience.

But with a recent poll indicating our two-term mayor to be more unpopular than ever, could it be that merely not being named Greg Nickels will be enough to catapult Donaldson, a health clinic owner, to City Hall’s loftiest perch?

“I wish it were so easy,” says Donaldson’s chief strategic consultant, Blair Butterworth.

So far, the mayor’s fundraising prowess and well-oiled political organization have scared away the likes of current city councilmembers Tim Burgess, Richard Conlin, and Nick Licata, as well as former city councilmember Peter Steinbrueck and developer Greg Smith. Steinbrueck is thought to be still mulling a run (see this week’s Uptight Seattleite for more), as is Stranger editorial director Dan Savage. Environmental leader Mike McGinn and executive headhunter Norman Sigler are the only candidates to have officially entered the race.

But an October 2008 poll commissioned by a potential challenger (SW agreed not to reveal who in exchange for its release) showed 53 percent of voters would prefer to vote for “another candidate” over the mayor, who garnered only 26 percent support (another 21 percent were undecided). In politics, however, there’s no such thing as a neutral canvas. “James Thurber was once asked ‘How do you like your wife?’,” notes Butterworth. “[Thurber] replied ‘Compared to what?'”

Of the aforementioned prospective rivals—not all of whom were included in the poll—only Conlin lost a hypothetical head-to-head with the mayor, and Nickels’ approval rating stood at a mere 31 percent. Six months on, it’s hard to imagine Nickels’ stature has improved. Voters identified as their top issue the economy, which has only worsened since October. Moreover, December’s snowstorms revealed a city scandalously ill-equipped to provide even the most basic public services when knocked off-balance by Mother Nature. Notoriously, Nickels gave his own administration a B grade for what most every other observer considered to be a D effort.

This all seems to suggest an ideal scenario for a “change” candidate in the Obama mold. “Sometimes you have to clean house,” says Donaldson, who’d previously declared his candidacy for city council before changing course. “That’s what this whole change phenomenon is about. Dissatisfaction in our country and in Seattle is at a tremendously high level. In my heart of hearts, I couldn’t stand to see our current mayor waltz to a third term uncontested. He needs to be challenged.”

Donaldson spent 15 years in the NBA, beginning his career with the Sonics in 1980. He spent just three seasons in Seattle, but called the city home each off-season, and has ever since.

Playing center for the Sonics, Clippers, Mavericks, Knicks, and Jazz, Donaldson posted career averages of 8.6 points and 7.8 rebounds. A solid but unspectacular player, Donaldson made his only All-Star team the same year a talented point guard named Kevin Johnson entered the league.

Johnson and Donaldson share a lot in common. Both played college ball in the Pac-10—Johnson at Berkeley, Donaldson at WSU—and both grew up in Sacramento, Calif., where Johnson was elected mayor this past November.

Like Donaldson, Johnson entered his race as a small business owner and novice politician seeking to topple a two-term incumbent, Heather Fargo, with formidable fundraising skills. Like Nickels, Fargo suffered from low approval ratings, but nevertheless scared off seasoned rivals.

“The incumbent mayor wasn’t particularly popular, and there was a feeling in the community that someone should take her on, but none of the conventional politicians did,” says Johnson’s campaign manager, Steve Maviglio. “She had multiple sclerosis, and some people were afraid to take on someone who was ill.”

Employing a strategy that can be expected to be used against Donaldson, Fargo sought to portray Johnson as long on celebrity and short on ideas and experience. Johnson’s campaign countered with a 26-page document outlining his vision for the city that was chockablock with specific initiatives. He also benefited from Obama’s coattails and star-studded visits by NBA greats Magic Johnson, Charles Barkley, and Shaquille O’Neal. And then there was this: “Another thing that Kevin brought to the table was he made himself a half-million-dollar loan,” says Maviglio. “So it was really hard for Fargo to make up that ground. We shattered all records, and so did she at the end of the day.” (Johnson’s campaign raised a total of $1.6 million, while Fargo raised roughly half that.) Johnson ended up coasting to victory with 57 percent of the vote.

Johnson entered the NBA at a time when individual salaries began to explode. He made $536,100 as a rookie while Donaldson made $500,000 that same year as a veteran All-Star. While the injury-prone Johnson earned $8 million for playing 50 games during the 1997–98 season, Donaldson netted $5.7 million for his entire 957-game career. Suffice it to say Donaldson won’t have Johnson’s financial wherewithal when it comes to writing checks to his own campaign; as of his Feb. 28 filing, Donaldson had given himself $4,475.

Donaldson has felt the effects of the economic downswing first-hand—he once owned four clinics in the area, yet now operates only the original Donaldson Clinic northeast of Seattle. Whatever his financial limitations, he believes “the NBA will be very helpful in my efforts.” He singles out the league’s Retired Players Association as one entity he expects to step up. Former Sonic Lenny Wilkens has already donated money to his campaign, and Donaldson counts Gus Williams, Gary Payton, Detlef Schrempf, Fred Brown, and John Johnson among his supporters.

Donaldson has also reached out to Magic Johnson and O’Neal—the latter to borrow suits—as well as to KJ. “I’ve let [James] know that if there’s anything he needs me to do, I’m certainly willing to do it,” says Sacramento’s mayor. “You’ve got to have the fire in the belly to do this, and I think he does. As an athlete, you’re used to being held accountable. In the world of politics, a lot of people don’t want to be held accountable.”

Johnson also feels as though there’s never been a better time to be a black candidate in America. “I think the results speak for themselves,” he says. “We have an African-American president, and me being the first African-American mayor of Sacramento speaks volumes. I’m not saying that race is not a problem, but the best of our country has really been reflected in these elections.”

Prior to the 2007 election cycle, Donaldson says, “I was truly an outsider looking in. I didn’t like politics and I didn’t like politicians.” But then Brian Ebersole, a former mayor of Tacoma who, like Donaldson, was active in Tacoma’s Rotary Club, convinced him to monitor the 2007 elections to see if they’d change his perspective. They did, at which point Donaldson, who once owned a clinic in Tacoma’s Hilltop neighborhood, told Ebersole, “Brian, this is my next passion.”

“The most impressive thing about James is that every Thursday for the past [eight] years, he has driven the 70-mile round trip [to Tacoma] to help tutor a second-grader at McCarver Elementary School on Hilltop without any fanfare,” says Ebersole. “He’s one of the most modest, kind, sincere, wonderful, good-to-the-core people I know. You feel like you’re in the presence of greatness, like the Dalai Lama or Jesus Christ. That’s pretty rarefied company. His motives are pure. He’s deciding to get into public office for all the right reasons.”

But in politics, nice guys often finish last, and Donaldson is no stranger to the question of whether he’s too genteel for his new career. “That is a common perception of me, even in the NBA,” he concedes. “But I learned to be tough, learned to stand my ground. People who know me know I can be very stern, very competitive. But I don’t wear my emotions on my sleeve, so I think that’s where the perception comes from.”

Adding to Donaldson’s choirboy image is the fact that he’s never touched so much as a cigarette—no alcohol, no drugs, and, for the past 20-plus years, no meat either. His vegetarianism, he says, is motivated by his love of animals. Last year he lost both his canines to illness, but will wait to replace them.

“My life isn’t conducive to raising a dog right now,” he says. “But win, lose, or draw, I’m gonna go out and get me a couple dogs.”