Columbia City is yuppie-friendly these days. Sure, there are still a few boarded-up storefronts and the occasional guttered beer bottle, but show up on a Saturday morning and you may as well be in Wallingford. Young, mostly white parents clog the sidewalks with their chocolate labs and their running strollers, spilling out of the local bakery, lattes in hand.

This formerly gritty south-end hood’s been changing for some time now, and some property owners say it’s time to take it to the next level. They want to form a Business Improvement Association—akin to a group effort to pretty the place up—something no neighborhood in Seattle has done in nearly a decade.

Others, however, say not only that it’s not necessary, it’s exactly the wrong time to be raising taxes just as the bleak economy is making it tough for folks to stay afloat. Plus, they fear it’s just another harbinger of more gentrification.

Seattle has six BIAs. The first, Pioneer Square, was formed in 1983. Others include Broadway, Chinatown/International District, West Seattle, University District, and the downtown Metropolitan Improvement District— the most recent, formed in 1999.

The idea behind a BIA is to share the cost of making a neighborhood cleaner and safer. The money comes from an assessment levied on commercial and multi-family property owners within the boundaries of the association. Once the boundaries are drawn, 60 percent of the property owners must approve the idea for it to move forward. The City Council has the final say on whether to create the association. It’s expected to vote on the Columbia City proposal this month.

BIAs often spring up when neighborhoods reach an evolutionary tipping point when property owners are no longer content just to sweep in front of their own shops, says Karen Selander, senior community development specialist at the city’s Office of Economic Development. “[BIAs] are effective because they address the entire area,” she says. “You don’t have two or three owners doing a good job maintaining their property, with others in between that are a mess. It helps avoid resentment.”

The city encourages the creation of BIAs and even invests in them, spending an average of $20,000 per neighborhood on consultants’ fees and in staff time to get them set up, Selander says. Although BIAs can be disbanded just like they are created, with a 60 percent vote of property owners, once they’re put in place, they usually stick around.

Robert Mohn, one of the organizers of Columbia City’s BIA, says that the business district there (located along Rainier Avenue South between South Alaska and South Dawson Streets) has reached a key point in its maturity. Columbia City has achieved two goals, he explains: to meet the immediate needs of the neighborhood—where one can shop, eat, buy groceries, see a movie, etc.—and to be a destination for others.

“The [BIA] is a part of Columbia City’s efforts to improve itself and be a great place for people to come enjoy themselves,” says Mohn, who a decade ago purchased the building now inhabited by the Columbia City Ale House and who also owns the historic Grayson and Brown building on Rainier Avenue South. “That’s what we’re trying to do. It’s another step in that direction.”

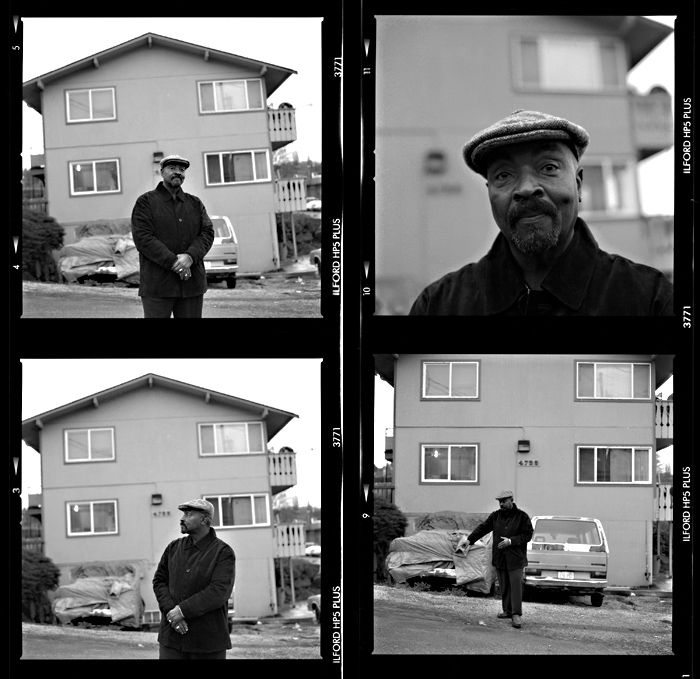

Not so fast, says James Buchanan, who with his 86-year-old mother owns a small apartment building on 38th Avenue South. Buchanan, whose family has owned property in the neighborhood for more than 30 years, argues that it’s up to the individual to keep things up.

“It’s part of the responsibility that comes with ownership. If anyone puts graffiti on the place, I buy a can of paint and clean it up. If someone breaks a bottle, I pick it up,” Buchanan says. “The country’s in trouble. I rent to low-income people. If I have to raise rents [because of the BIA], they might not be able to stay…If other people want to do this, fine. We can’t afford it.”

Buchanan’s modest and decently maintained four-unit apartment building sits a block off Rainier behind a giant U.S. Postal Service complex. He’s skeptical of what benefit the BIA would provide to him. “I don’t even have sidewalks on my street,” he says.

Mohn argues that all property owners will get their fair share of the pie. “Every ratepayer will get service,” he insists, adding that the fees are modest— most property owners will pay less than $1,000 a year. He says three-quarters of the fee is based on property size and one-quarter on value, so the assessment will stay relatively steady. “We don’t want this to keep increasing,” Mohn says, adding that 70 percent of the owners within the proposed boundary have approved the idea. The BIA’s total annual operating budget is proposed to be $50,000.

Ron Soreano, who with his family owns Soreano’s Hatfield Plumbing and three other Columbia City parcels, says the price may be modest, but it’s the principle that bothers him.

“This is about the Johnny-come-latelys. We’ve been through the rough times. Columbia City [today] is cake,” Soreano says over a latte at the Columbia City Bakery (one of the favorite hangouts for the running-stroller types, ironically).

Twenty years ago, Soreano’s Mercer Island customers wanted him to ship parts to them rather than make the 10-minute drive to his shop. “They didn’t want to come here,” Soreano remembers. “Now they say, ‘I’ve heard of Columbia City. There’s a bakery there and a nice Italian restaurant, I’ll come over.’…It’s like a new Fremont, but more diverse in color.”

“I pick up my own neighborhood,” he adds. “I don’t need somebody else to do it.”

Columbia City isn’t the only new BIA in the works. Property owners are attempting to form similar associations in Lake City and in the Central District neighborhood around South Jackson Street and 23rd Avenue South.

The BIA planned for Lake City is especially ambitious, with a proposed annual budget of $250,000 and an agenda that includes cleanup, security, marketing, professional management of the association, new Lake City banners on the boulevard, and “ambassadors” strolling the neighborhood’s core answering newcomers’ questions.

“We have a lot of new buildings, some upscale businesses,” says Lake City organizer Dave Howry. “There are plans to build more multistory housing. The whole area doesn’t want to just be a drive-through. We want to improve livability.”

Lake City has 43 percent of its property owners on board, with hopes to have the requisite 60 percent and city council approval by the first of the year so the association can start billing property owners come June.

But not every Seattle neighborhood is on board. Earlier this year, some businesses on Capitol Hill tried to form a BIA-like group for the Pike/Pine corridor, but failed to get the requisite support. A similar effort also failed in Belltown.

Chip Ragen, a property owner who organized the Capitol Hill effort, attributes the lack of interest to the “culture of independence” on Capitol Hill. “There’s a greater number of smaller property owners,” he says. “Some who live out of state and are not real engaged in the community, and some [who] have a philosophy of you do your own thing, we’ll do our own thing.”

As with Columbia City, Ragen says it was the newer investors who were more willing to pool their resources. “People who have owned their property for many, many years have their own program of painting out graffiti. They saw this as an annoyance that’s going to take control away from them.” Ragen adds that the sour economy didn’t help.