OLYMPIA — Tim Eyman’s trial for allegedly breaking state campaign finance laws is getting pushed back on the calendar again.

The former Mukilteo resident’s trial, which was set for January, has been moved to July 13, 2020 in Thurston County Superior Court.

In the meantime, the cost of the state’s legal pursuit is averaging more than $40,000 a month and could top $1 million soon.

Attorney General Bob Ferguson has accused Eyman, a Bellevue resident, of secretly moving funds between two initiative campaigns in 2012 and receiving $308,000 in kickbacks from the firm that collected signatures for both measures.

Ferguson filed a lawsuit in March 2017 seeking $1.8 million in penalties plus reimbursement of the funds Eyman received from the signature-gathering firm, Citizen Solutions.

And, if successful, the attorney general also wants the court to bar the anti-tax activist from “managing, controlling, negotiating or directing financial transactions of any kind for any political committee.”

“We did not ask for a July 2020 date,” said Brionna Aho, Ferguson’s communications director. “Our only concern about the new date is a further delay in a court order stopping Mr. Eyman’s unlawful conduct.”

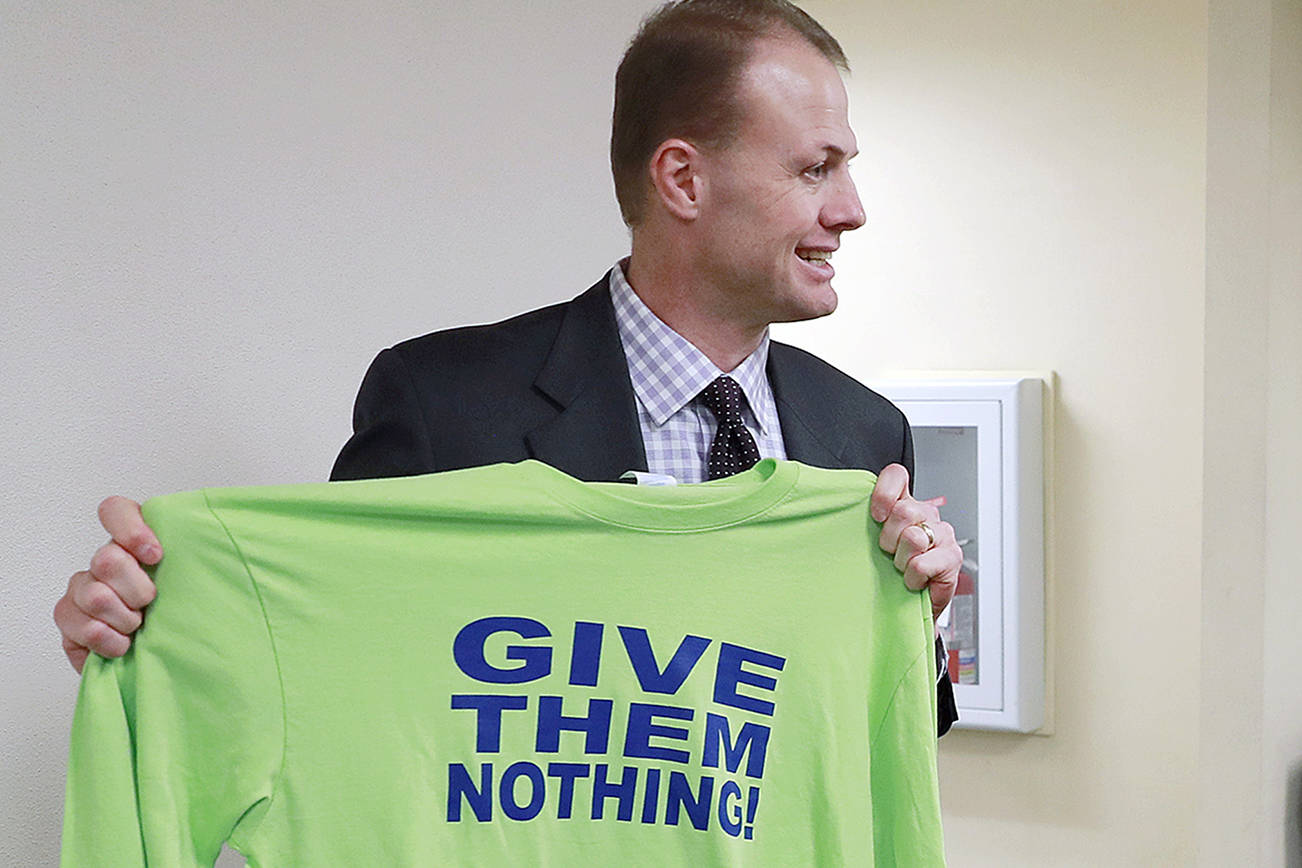

Eyman has denied wrongdoing. He said in a recent interview he isn’t bothered by having to wait longer to prove his innocence.

“It gives me eight more months to be politically active,” he said.

Meanwhile, the cost of the state’s legal pursuit — which is borne by the state Public Disclosure Commission — continues to mount.

Between July 1, 2017 and March 31, 2019, Ferguson’s office billed the enforcement agency $890,129 for handling the case. Most of the expenses are for the civil case though a portion is tied to proceedings triggered by Eyman’s bankruptcy filing at the end of November.

Of the total, $487,399 covered the 2018 fiscal year, and $402,730 is for the first nine months of the current fiscal year. For those 21 months, the state’s tab is averaging $42,387 per month. At that pace, the state’s legal bills will break $1 million by June 30, the end of the current fiscal year — and there will be another full year of legal maneuvering until the trial.

Aho said the bulk of the billings are related to Eyman’s delay in responding to discovery requests. Superior Court Judge James Dixon has found Eyman in contempt for not turning over documents sought by the state and the fines are mounting daily.

“We can’t predict Mr. Eyman’s future conduct,” she said. “Once discovery closes, there likely will not be much activity in the case until trial.”

Under the new timeline, discovery is scheduled to close Feb. 14, 2020.

Eyman said his expenses aren’t climbing because he is serving as his own lawyer.

“Because the attorney general has effectively blocked me from having an attorney, the later court date doesn’t cost me anything,” he said.

This legal dispute began in 2012 with a complaint to the Public Disclosure Commission. It alleged Eyman failed to report that he was shifting money donated for Initiative 1185, a tax-limiting measure, into the campaign for Initiative 517, which sought to reform the initiative and referendum process.

Under state election law, money can be moved from one political committee to another, but it must be disclosed in reports to the commission. And the sources of the money that is getting shifted must be revealed as well.

Commission staff conducted an exhaustive three-year investigation. It relied on bank records, emails and interviews to diagram how Eyman steered payments through his political committee, Voters Want More Choices, to Citizen Solutions knowing a portion of the money would be paid back to him for personal use and political activities.

In the course of the PDC probe, investigators found Citizen Solutions had been paying Eyman in prior initiative campaigns as well.

Commissioners, after reviewing the findings, referred the case to Ferguson because they believed the violations were egregious and the attorney general could exact greater penalties than the commission. Also, commissioners wanted Ferguson to investigate whether the alleged web of deceit their staff documented might have begun years earlier and might still be going on.

Ferguson’s office did its own investigation before filing the lawsuit. State attorneys have since amended its original complaint to include additional allegations related to Eyman’s fundraising activities since 2012.

The Eyman case continues to be the commission’s largest billing from the Attorney General’s Office.

If the state wins the case and recovers money for attorney fees and penalties, the commission would be in line for reimbursement.

Jerry Cornfield: 360-352-8623; jcornfield@herald net.com. Twitter: @dospueblos.