A year ago around this time, an ambitious young educator named Hannah Williams was getting ready to take advantage of the state’s new charter-school law. She had a master’s degree from Harvard, a plan for a freewheeling, project-based curriculum, and a $100,000 grant from an organization funded largely by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Last month she announced that she was suspending her effort. After getting turned down once by the state Charter School Commission, she decided not to apply again. Other once-hopeful charter-school founders made similar decisions. Whereas the commission received 19 applications last year—its first following the 2012 charter initiative—it took in just four this year.

In the end, as the commission sat to evaluate those applications last week, it approved just one—for a school in South Seattle to be run by California’s Green Dot Public Schools. Spokane Public Schools, the only district in the state that also acts as a charter “authorizer,” approved another one. Still, the total is paltry when you consider that the law allows eight new charter schools each year—a figure hit in the first round of approvals after turning down 12 applications.

What gives? Well, for one thing, the commission’s tough standards seem to have brought on a process of self-selection. Last week, members questioned how well a group wanting to work in the Yakima Valley could work with the dominant Latino population there. Then the commission rejected the application. In 2013, it turned down 12 applications. The commission’s denial to Williams, for example, identified educational, organizational, and financial concerns.

In the aftermath, Williams says, she unexpectedly found herself spending all her time developing a board. “That’s not my strength,” says the former Aki Kurose Middle School theater and music teacher. She says she had trouble finding people with financial skills, and didn’t even get around to actual fundraising.

And fundraising is something a new charter school has to do. While by law charter schools get the same per-pupil state allocation as other public schools, that funding only starts flowing once a school is already open and the state has students to count. Before that, a school has to do many things, commission chair Steve Sundquist explains: “find students, hire teachers, find a building, begin lease payments, maybe retrofit the building.”

“It’s a big lift,” he acknowledges. And even once a school starts getting state funding, it won’t receive local levy money until voters tax themselves anew (the rationalization being that they weren’t voting for charter-school funding when they taxed themselves the last time). That’s a significant chunk of the budget for regular public schools—about 25 percent in Seattle, according to Sundquist, a former school board member here.

If that weren’t daunting enough, the commission added a new requirement this year: Applicants have to show that they are already engaging the community they intend to serve, not just that they plan to do so. The intent, Sundquist says, was “to make sure that the potential school is going to find a good reception.”

That seems like a smart move given the decidedly different opinions on charter schools in this state, as shown by the close vote on the 2012 charter initiative that set the new system in motion. Likewise, the commission’s overall toughness seems warranted by the mixed record charter schools have had elsewhere, with some exceptional schools and many mediocre ones.

“I’m less worried about the numbers than trying to provide high-quality schools,” Sundquist affirms.

Meanwhile, however, some feel that the numbers are already too high. That’s not so much because of the latest approvals, but because of the eight green-lighted in the last round, most of which are just now recruiting students for a planned 2015 opening.

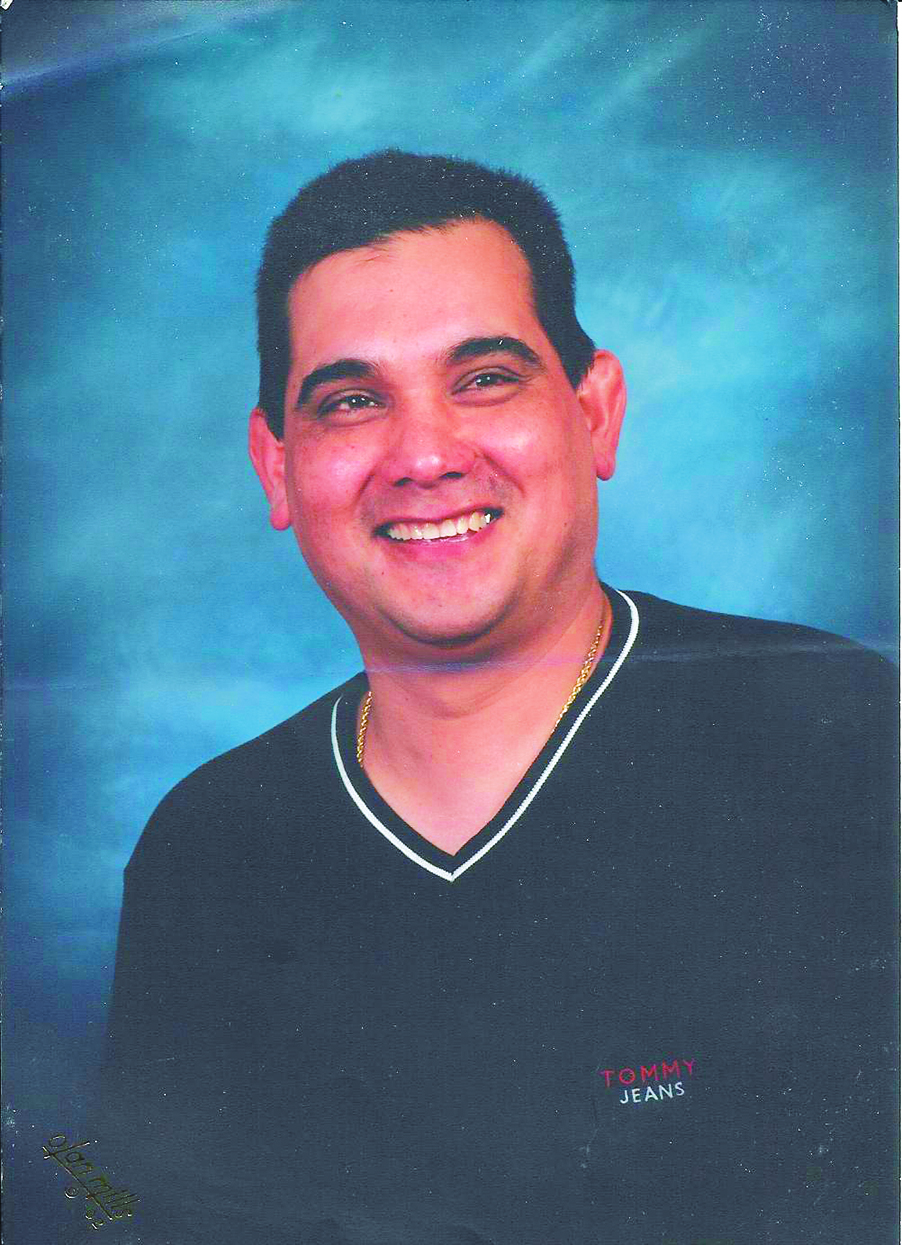

Kristina Bellamy-McClain. Courtesy SOAR Academy

“It’s full steam ahead,” enthuses Kristina Bellamy-McClain, founder of SOAR Academy in Tacoma and a former principal of Seattle’s Emerson Elementary. She’s launched a website and planned community forums, and is asking volunteers to talk up the school at farmers markets and carnivals. In less than two weeks of trying, she’s received nine applications. “I’m feeling pretty good about that,” she says.

She hopes to get 100 students this year—and 450 by the time she phases in all grade levels of the planned K-8. Two other approved charter schools in Tacoma hope to enroll another 1,000 combined. And that’s got the school district there very nervous.

By law, charter schools receive money from the state on a per-pupil basis. If Tacoma’s three charters fill up, their total funding will add up to $10 million a year, says Karen Vialle, a former Tacoma mayor now serving on the school board there. That’s $10 million that the district won’t get.

“We will be laying teachers off,” Vialle says, adding that larger class sizes will result.

The same could happen in Seattle, says this city’s school board president, Sharon Peaslee. First Place Scholars, the only charter school in the state yet open, located in Seattle’s Central District, was previously a private school, and so had an existing student population not drawn from the public schools. That’s not the case, though, with two more schools set to open in Seattle. Those—Green Dot’s and one by another California operation known as Summit Public Schools—eventually plan to enroll a combined 1,700 students.

“It could have a very damaging impact,” Peaslee says.

It’s hard to say how many more charter schools might be coming down the pike, given the drop-off in numbers. Still, the Tacoma board is considering lobbying the legislature to change the law in a way that instructs the commission to consider how many charter schools are in any given city. Commission Executive Director Joshua Halsey says the state body could also insert language into its next request for proposals that will encourage applications from under-served areas.

At the same time, Bellamy-McClain says she’s hoping that the Tacoma district, at least, will warm to charter schools. Hers targets a predominantly poor, minority student population that she says is largely “underperforming” in regular public schools. Why not let SOAR Academy take a crack at it?

“I continue to believe we will be able to come together with Tacoma Public Schools and talk about wonderful opportunities and partnerships,” she says.

nshapiro@seattleweekly.com