(Editor’s note: This story has been modified since it was first published. We have removed the names of the two children involved, at the request of their dependency attorneys.)

Years before she was rescued from virtual imprisonment, Janet (not her real name) tried unsuccessfully to run away from home.

On a spring afternoon in March 2005, 11-year-old Janet, accompanied by one of her elementary-school classmates, opted out of her usual bus ride home and fled for the safety of somewhere other than her parents’ Carnation residence. Hours later, a local man called Carnation Elementary School’s main office to report that the two had arrived at his house a few miles away, and were resting on his front lawn. They were eventually returned to the custody of school officials. There, months of silence gave way to confession as Janet revealed the real reason she had bolted: fear.

According to witness statements given to investigators from the King County Sheriff’s Department, Janet begged her teachers, including Susie Marshall, not to send her home. “Please don’t call my dad,” she said. “He won’t believe me.”

Per the guidelines of the Riverview School District’s homeschooling program, Janet attended Carnation Elementary two days a week—often enough for at least two of her teachers to notice the slightness of her frame. Still, they didn’t suspect just how bizarre the disciplinary methods at the Pomeroy household had become.

“From what we could tell, no one had any idea that this was going on,” says Carol Gould, one of Janet’s instructors.

Each morning after her father, Jon Pomeroy, a software engineer at a Bellevue information technology firm called Estorian, left for work, Janet remained locked inside a windowless room in a converted garage while her father’s wife, Rebecca Long, slept. To use the bathroom, she told her teachers, she had to bang on the wall to alert her younger brother that she needed to go.

More harrowing details of her situation followed. Janet was not allowed to play outside with her friends or use the computer or phone, she said. Her only full meal came in the evening, after her father arrived home from work and prepared dinner. Beyond that, the only food she was allowed each day was the two pieces of toast given to her when Long awoke each afternoon. Her stepmother, Janet added, “hit her a lot.”

Marshall, who declined to comment for this story, placed a 911 call later that afternoon. Kevin Stackpole, a deputy with the King County Sheriff’s Department, arrived at the school to investigate. He noted, in agreement with Marshall, that the then-11-year-old Janet appeared thin—but he could see no bruises or other obvious signs that she was being physically abused.

Jon Pomeroy eventually arrived at the school. Questioned about Janet’s allegation that his wife had been leaving his eldest child locked inside her room, Pomeroy claimed he wasn’t aware of the situation. (Janet would later tell investigators that her stepmother warned her not to tell anyone.) Upset at the revelation, her father admitted that his long work hours kept him away from home, and that his wife and daughter had a tendency to “push each other’s buttons.”

Pomeroy, now 44, collected Janet from the principal’s office and took her out to dinner. While the pair was away, Stackpole went to the family’s home near Lake Marcel to question Janet’s stepmother. There Long confirmed that relations with her stepdaughter had been chilly since 2001, when Jon, his kids in tow, made the trek from Utah to live with Long in Carnation. The two met while working together for WordPerfect at the word-processing giant’s Orem, Utah, headquarters. They began dating before Long moved to Washington, and were eventually hitched in 2005.

The 45-year-old Long copped to locking Janet inside her room, explaining that she did it so Janet would not “come out and take things.” Her teachers at Carnation Elementary told investigators that they had no record of stealing from other students. School officials at Stillwater Elementary, Janet’s previous school, said the same. But Long insisted that while Janet had been enrolled there years earlier, she had gotten into trouble for taking things from other students without their permission. When asked, Long claimed to be unaware that confining a person to an enclosed space with no exits was against the law.

State law prevents law enforcement and Child Protective Services (CPS) from removing a child from a caregiver’s custody unless it can be determined that there is an imminent risk to that child’s safety. Satisfied that there was no such risk after finding Janet’s younger brother (whom we’ll call Carson) in good health—and after the Pomeroys promised to remove the locks on Janet’s door—Stackpole departed.

A CPS social worker came to the same conclusion after her own visit to the Pomeroy home a few days later. In an interview, Janet suggested some level of détente had been achieved between her and Long. She also took back some of her previous statements about her diet, saying that there was food available in the house but that she sometimes simply chose not to partake out of frustration.

Long had ceased locking her inside her room, she added. Yet there remained a lingering discomfort between the two. Asked why, Janet replied, “‘Cause when I get in trouble, most times there is a reason and sometimes there isn’t.”

A few weeks later, teacher Marshall called the CPS social worker assigned to Janet’s case, worried that Janet had not been to school since the March incident. The investigation was closed the following month, though the allegations against Long had been determined “founded.” The report’s final entry describes Janet’s home environment as “low risk” safety-wise, and mentions that her parents had taken “appropriate steps” to address issues at the home.

Three years later, after Janet’s prolonged screaming drew King County Sheriff’s deputies back to the family’s home, Pomeroy and Long both pled guilty to felony criminal mistreatment in the first degree. Last month, a King County Superior Court judge sentenced Pomeroy to the maximum penalty—41 months—allowed by state law.

Unlike her husband, Long entered a special plea: All she’s required to admit is that there is enough evidence to convict her. She’s asked the court for leniency, citing what her attorney Robert Wayne described as a history of mental illness. At a hearing last month, Wayne indicated that Long suffers from dissociative identity disorder, a psychiatric ailment more commonly known as multiple personality disorder. Due to the private nature of medical records, documentation of Long’s ailing psyche is unavailable, and Wayne would not speak to the specifics of her mental-health status. She’s submitted to a private mental-health evaluation, the full details of which won’t be made public until her sentencing hearing.

Whether a judge will accept Long’s alleged mental-health issues as a mitigating factor is a question that won’t be answered until then. But as a definitive explanation for why a caregiver would, as a disciplinary tactic, withhold food or water from a child in such a manner that the act itself becomes prosecutable, many in the medical and psychiatric communities remain unconvinced. According to mental-health and child-welfare experts, the form of child abuse suffered by Janet is particularly rare. And yet in Washington state, there have been a handful of recent high-profile cases of this very nature, each of which involved a victim who was to some degree failed by the state’s Child Protective Services department.

Standing on the porch of her home in August 2008, Janet, then 14, told a King County Sheriff’s deputy that she couldn’t continue living with her family. Officer Kurtis Wayerski had arrived minutes earlier to perform a “welfare check” after Child Protective Services received an anonymous call from one of the Pomeroys’ neighbors reporting that, the night before, a child had been screaming uninterruptedly from somewhere inside the home for over half an hour.

Janet’s old room was in the process of being converted back into a garage, and she and her brother had been sleeping on the floor near their parents’ bed. On the night in question, Long accidentally stepped on her stepdaughter. Agitated from heartburn, and upset at Long’s refusal to provide her any water for relief, Janet said she was “unable to take it anymore” and began screaming.

Roused by Wayerski’s knocking, Jon produced his daughter at the deputy’s request. Janet came to the porch wearing shorts, a T-shirt, and a scowl. The officer tried to break the ice by offering her a sticker, but Janet refused and continued to gaze at her feet, unwilling to look Wayerski in the eye. After a few minutes she opened up, eventually confiding, “I can’t deal with living here anymore.”

Janet was pale and skinny, wrote Wayerski in his report. He asked her how much she weighed. She replied that she didn’t know, but that her father had recently bought a new scale. The officer asked Jon to retrieve it, and he led the officer through the cluttered home to the master bedroom. Janet weighed 48 pounds, and was measured at 4’7″. Doctors would later say that over the previous four years, Janet had actually lost weight, hardly the norm for a girl at that stage of physical development.

Before Wayerski departed, he told Long and Pomeroy that a representative from CPS would soon be contacting them. He advised them that Janet seemed “severely malnourished,” and that her emotional troubles were palpable. Wayerski would later write in his report that he believed a CPS intervention was “necessary,” but left Janet in her parents’ care. Before the officer departed, Long told him that the family would welcome contact with CPS.

“We need help,” she said.

The gory details of Janet’s living situation weren’t apparent until after sheriff’s deputies and CPS agents took her into protective custody this past August 22. According to Janet’s statements to police, beginning sometime after Janet turned 13, Long began limiting her stepdaughter’s water intake. Both parents said that they had previously utilized all of the more socially accepted forms of discipline: timeouts, discussions, spankings. But as Janet entered her teenage years, the dynamic between she and her stepmother began to worsen. Long became the gatekeeper of Janet’s water intake; her average ration was only six ounces per day. (Solicitations for comment from CPS and law-enforcement personnel directly involved with Janet’s case were unsuccessful.)

Long’s attorney Wayne declined to comment for this story, citing his client’s upcoming sentencing hearing. And multiple attempts to reach Long were unsuccessful. She had, however, told investigators that the rationing began as a method of teaching her stepdaughter that she “needed to ask for things.” When she didn’t, or when Janet’s attempts to sneak water were discovered, Long became stricter. In one incident, Janet sneaked into the bathroom to drink water from the toilet. In response, Long began pushing a heavy dining table in front of the door of Janet’s room each night to barricade her stepdaughter inside. She also began to oversee Janet’s trips to the bathroom, watching her as she bathed and brushed her teeth to prevent her from drinking from the showerhead or faucet.

During this time, Janet would periodically refuse to eat, sometimes going 24-hour stretches without a meal. Pressed by social workers later, Janet chalked it up to lack of appetite due to depression—and to the difficulty she sometimes had swallowing dry food for lack of saliva.

As their predicament grew more bizarre, Janet and her family became more isolated. Janet was often kept locked in her small, unheated room, which had become infested with worms, according to documents obtained from the King County Sheriff’s Department. And she and Carson were both pulled out of the Riverview School District by their parents following Janet’s 2005 runaway attempt. Janet later told police that in addition to water, Long had withheld reading and educational material while locking her inside the house. There were, however, some books; when police officers searched the Pomeroy house, they found a copy of Jane Yolen’s Girl in a Cage, the story of Sir Robert Bruce’s captive 11-year-old daughter, on the coffee table.

On August 15, two days after King County Sheriff’s deputies were called to the house, Long took her stepdaughter to a University of Washington–run neighborhood clinic in Bellevue for her first medical evaluation in nearly four years. Nurses there immediately took note of her condition and made two phone calls: one to file their observations with CPS, and another for an ambulance.

Janet was transported to Seattle Children’s Hospital, where doctors confirmed the results of the nurses’ examination. Her teeth had eroded from vomiting acid from her frequently empty stomach. She was emaciated and suffering from severe dehydration exacerbated by chronic diarrhea—traits common to concentration-camp survivors, physicians remarked.

In an interview with investigators, Long told Detective Michael Gordon that she was unaware that withholding water from Janet could result in severe medical consequences. Moreover, both she and her husband claimed to be unaware of the physical toll this had taken on their daughter’s body.

Conversely, Janet seemed to have at least a cursory knowledge of her own physiology. Asked by Gordon about the color of her urine, she said that while at home it was darker, remarking that there was “not enough fluid.”

According to court documents, Jon Pomeroy knew about the water restrictions and the forced isolation, but still had chosen not to intervene. He’d later tell investigators that he’d been oblivious to his wife’s mistreatment of Janet, and that it was his understanding that she had not been withholding water from her, but merely requiring her to ask for it politely. He recanted when the time came to enter a plea.

Pomeroy’s attorney, Kevin Donnelly, declined to comment for this story, saying that he was not authorized by Pomeroy to speak to the press. And calls to Pomeroy prior to his sentencing went unreturned. But Zachary Wagnild, the prosecutor assigned to both parents’ cases, says Pomeroy changed his story to spare his children the added trauma of testifying against him. “I think he genuinely felt remorse for having checked out of the situation,” says Wagnild.

As for Long, her mother Martha, reached by phone at her home in Sulphur Springs, Louisiana, insists that her daughter is nothing like the person the media has depicted her as. “Her reputation has been permanently blackened,” she says.

On April 12, 2005, almost a month before Janet and her friend walked away from Carnation Elementary, the state Office of the Family and Children’s Ombudsman issued its findings on the deaths of Justice and Raiden Robinson. Sixteen months and 6 weeks old respectively, the two brothers were found dead from starvation and dehydration on the floor of their Kent apartment in November 2004.

Responding officers from the Kent Police Department found the boys’ mother, Marie Robinson, passed out in her bedroom among 300 or so empty beer cans. Chief among the Ombudsman’s office’s findings was that Child Protective Services had had ample opportunity to intervene on behalf of the Robinson brothers, but, due to a variety of lapses in oversight, failed to.

In the two years preceding the boys’ deaths, CPS received six referrals (reports filed with CPS authorities regarding an alleged case of child mistreatment or abuse) regarding Robinson’s maltreatment of her sons. Two of these referrals were actually investigated: The Ombudsman’s office found a CPS probe into an October 2003 allegation of child neglect lacking, and the agency’s investigation of a separate allegation received in February 2004 was still pending when police found Justice and Raiden dead nine months later.

“The agency failed to adequately investigate referrals it received on the Robinson family despite numerous opportunities to do so,” wrote Mary Meinig, director of the Ombudsman’s office. “If they had properly investigated the referrals on a timely basis, the outcome may well have been different.”

Beyond reviewing CPS’s performance, the Ombudsman’s office made a number of recommendations for ways the agency could improve its investigation and intervention protocols to prevent any more tragedies like Raiden and Justice’s—chief of which was a reasonable cap on the number of cases handled by a given social worker.

“In these investigations, what you have to look at is what might have been going on in that office that contributed to the lack of follow-through, specifically if the social worker was overburdened by case loads,” explains Meinig. “It’s gotten so bad in some offices where we’ve had supervisors who have had to go out and do investigations themselves because their workers were so overloaded. They’re having to triage cases for priorities, and that puts kids at risk.”

Mary Ann Murphy, board member of the Washington State Council for Children and Families, a state agency which facilitates efforts to prevent child abuse, says caseworker overload is due in part to a common ailment among government agencies: lack of funding. Despite efforts to increase services statewide, Murphy says CPS is “not given enough resources to do a comprehensive job with every one of these cases that come to their attention.”

The number of open cases carried by the social worker assigned to investigate referrals regarding the Robinson clan was 37 in October of 2003 and 49 in October of 2004. The part-time investigator who handled the 2005 complaint concerning Janet was underworked by comparison, carrying just six open cases at the time the CPS received the referral.

If that 2005 investigation had a flaw, says Meinig, it may lie in CPS policy, which does not include a mechanism for following up with those children who have been pulled out of school following allegations of abuse. “It’s a situation that we’ve seen before, where the school has made a referral and suddenly the youngsters are no longer attending,” explains Meinig. “Do we know what necessarily happened to these kids? No. There’s no protocol for follow-through.”

Officials with the Children’s Administration, the branch of the state’s Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS) that operates CPS, contend that efforts to reduce the number of cases carried by each social worker have been ongoing since the late ’90s. In 1997, CPS social workers were carrying an average of 40 open cases each. By 2002, that number had dropped to 20. That same year, the state of Washington reached a $1.3 million settlement with 12-year-old Jessica Braam and 12 other foster children who claimed to have been placed in harm’s way by DSHS procedures. One of the requirements of the settlement was that DSHS decrease the case burden on its social workers. Afterward, CPS received additional funding from the state to fill vacant positions and hire additional staff, says Sherry Hill, a Children’s Administration spokesperson. According to the latest report, the ratio of open cases to social workers through the first two quarters of 2009 was 18 to 1.

Yet lapses in CPS oversight continue to occur. Recent years have brought a string of high-profile embarrassments centered on the agency’s failure to detect and intervene in cases where children, like Janet, were being purposefully denied their most basic needs: food and water.

So thirsty was Tyler Deleon on the night before his seventh birthday that he ripped a hole in the screen of his bedroom window to eat the snow collecting on the ground outside his family’s home in the eastern Washington town of Deer Park. Weighing just 28 pounds, he died the next morning of severe dehydration. Carole Deleon, adoptive mother of Tyler and five other children, was eventually tried and convicted in Stevens County Superior Court on charges of homicide-by-abuse.

Court records indicate that Tyler was not the only child of Deleon’s to be withheld basic sustenance. Four of the other children in Deleon’s care, in addition to Tyler’s estate, have filed a $55 million lawsuit against the state and DSHS for failure to protect them from the abuse and neglect they suffered in Deleon’s home. In the aftermath of Tyler’s death in 2005, Governor Christine Gregoire required CPS to complete investigations into all high-risk child-abuse complaints within 24 hours of their submission to the agency.

In a more recent case, Danny Abegg and his girlfriend, Marilea Mitchell, were both found guilty of criminal mistreatment after authorities found Abegg’s youngest son Shayne wasting away inside the couple’s Everett home in March 2007. For nine months, the couple had been withholding food from Shayne and his older brother as punishment. According to court documents, when deputies from the Snohomish County Sheriff’s Department were called to conduct a welfare check on the then-4-year-old, they found he was suffering from hypothermia due to his low body weight, reporting that his “bone structure was readily visible.” At the time of his rescue, Shayne weighed just 25 pounds.

An executive review of the case conducted by DSHS detailed CPS’s lapses in oversight. Numerous complaints had been filed with CPS detailing Shayne’s abuse at the hands of Abegg and Mitchell, yet officials “missed several opportunities for more intensive intervention,” and closed the case despite requirements that it first be reviewed by a team of staffers. The review committee also took to task the social workers who handled the case, saying that they had failed to recognize a pattern of abuse on Abegg’s part, and that they “failed to provide adequate oversight” of the parents to ensure that they were implementing recommendations for Shayne’s care.

The state was eventually sued over that case too. Through his guardian, Shayne Abegg’s estate settled with DSHS for $5 million, and both Mitchell and the elder Abegg were handed eight-year prison sentences by Snohomish County Superior Court.

Shortly after news of Janet’s situation broke, the Pomeroy home, which sits on a lonely cul-de-sac near Lake Marcel, suddenly became a destination.

“People were appalled after they heard [about Janet’s mistreatment],” says Jordan Jessen, who lives across the street from the Pomeroy house. In the days following, a steady stream of cars filled the street. Some passengers came to gawk, others to leave nasty notes. “There was hate mail just covering the trees around the house,” remembers Jessen.

The Pomeroys weren’t outgoing people, says Jessen. Occasionally he and Jon would exchange the odd morning or afternoon greeting, or Carson would play with the Pomeroys’ golden retriever on the front lawn. But in the three years he’s lived in the neighborhood, Jessen cannot once remember seeing Janet.

“I didn’t know they even had a daughter,” he says. “I had no clue.”

Other neighbors questioned by investigators said they had not seen Janet in years. Not Suzanne Murdoch. She made the call to CPS after hearing Janet wailing inside her parents’ room. Murdoch told investigators she’d seen the girl just days before that incident, remarking that Janet “looked like someone out of a concentration camp.”

Murdoch said her interactions with the family had been brief. But years ago, on those rare occasions when her stepmother left the house, Janet would sometimes sneak over to the Murdochs’ to play with their daughter, then sneak back before either of her parents returned.

Calls to Murdoch’s residence went unreturned. But according to their statements to detectives investigating the case, she and her husband Steven knew as much about the Pomeroys as anyone—which is to say that they did not know them at all.

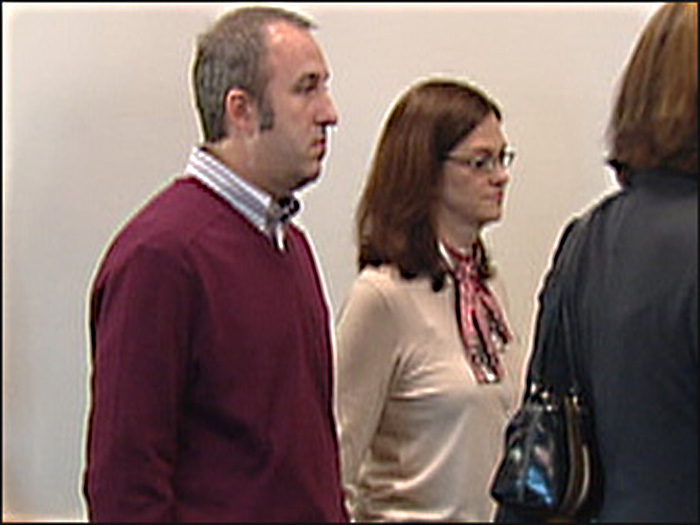

Their privacy stripped away, Pomeroy and Long’s relationship imploded. At an arraignment hearing in October 2008, the couple held hands as they exited the courtroom. But by late July 2009, Long had filed an order of protection with King County Superior Court prohibiting her then-estranged husband from coming within 500 feet of their Carnation home or her person.

In her filing, Long paints a picture of Pomeroy as a controlling physical abuser who kept her marooned in the house, much as she did their daughter. But it wasn’t until after their arrest, she alleges, that he became somewhat unhinged. “Jon keeps threatening to burn the house down around us, ‘fuck all this bullshit,’ let’s just torch it,” she wrote, adding that Pomeroy “anally raped me.”

In a letter submitted to the court just before Pomeroy’s September sentencing hearing, Wayne, Long’s attorney, claimed that the stress of living with Jon’s alleged abuse, and Long’s mental history, were partly to blame for her behavior. But according to Lucy Berliner, the director of Harborview Hospital’s Center for Sexual Assault and Traumatic Stress, mental conditions like multiple personality disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder may contribute to “people behaving badly,” but they don’t cause the poor behavior in and of themselves. “Most people who have them don’t conduct themselves in those ways,” adds Berliner.

Withholding basic sustenance like food and water from a child is equally uncommon, she notes. So rare is it, in fact, that few if any causational studies have been conducted. And trustworthy figures tracking how many cases occur each year are equally difficult to come by.

A 2005 article in the Journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics on criminally prosecuted cases of child starvation seems to bear out this peculiarity. The topic of frequency is covered only in the introduction, saying of cases involving the deliberate starvation of a child that the actual source of the behavior is unknown. Furthermore, the most recent report from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services estimates 1,760 child fatalities from abuse or neglect nationwide in 2007, but it does not specify how many of those were due to denial of food or water as a punishment.

“We can’t do studies unless we have enough cases, otherwise we’re all just speculating,” says Berliner, adding that it will take a series of case studies before any real determinations can be made. “As such, there is no psychiatric profile or syndrome generally thought to account for this particular brand of child abuse.”

Dee Wilson, a former administrator with the state DSHS who’s currently a lecturer at the University of Washington School of Social Work, generally agrees with Berliner. There are, however, similarities among these cases, he posits. “When you talk about parents deliberately stopping, or severely limiting, the food intake of children this age, it almost always occurs in the midst of a power struggle between the caretaker and the child,” says Wilson.

According to him, the pattern unfolds thus: Like most victims of child abuse, the children in these cases tend to be younger and more dependent on their caretakers. The abuser usually has some rational concerns about the child’s behavior, but when more accepted forms of discipline fail, they begin to experiment. The parents then shut themselves off, insulating the family, including the juvenile victim, from outsiders who might question their methods.

“Restricting movement is also fairly common,” Wilson adds. “Usually that involves locking the kid in rooms, which itself is another form of emotional abuse.”

The actions of the abuser, often someone who does not have a strong emotional connection to the victim, will escalate, becoming, says Wilson, bizarre or even criminal—but not necessarily insane.

“It isn’t a matter of psychiatric ailment in these cases,” says Wilson. “The parents are just extremely stubborn. They have some beliefs about the right and authority of parents to control their kid’s behavior. Usually, the kid has gotten to them in some way. That’s when they get into this power struggle, and they will go to practically any lengths to win.”

Of her relationship with Janet, Long told authorities that she never wanted to be a stepmother. All their problems started there, she said.

The nadir of Long’s relationship with her stepdaughter occurred sometime around the end of 2007. In police reports and court documents, this bottoming-out is referred to as the “toilet incident.”

According to Janet’s recollection, it began on the second floor of the Pomeroy home. She had been “talking back” to her stepmother all day, and in response Long was brandishing a shoe, with which she planned to spank Janet. This was a common occurrence in the Pomeroy household.

“I talk back a lot,” Janet told investigators. “It’s hard to keep my feelings back because I’m depressed all the time, and I’m always having bad dreams about her attacking me.”

In her attempt to discipline Janet, Long fastened some duct tape over Janet’s mouth, using it also to bind her hands—tightly enough to cut off circulation. Long then dragged her stepdaughter to the shower, where Janet says she attempted to overcome the tape and drink from the showerhead. Long finally dragged her to the toilet and, according to Janet, twice shoved her head into the toilet water.

Long later apologized, but the “power struggle” she told King County detectives she’d been locked into with Janet continued unabated.

Dr. Emiko Tajima of the University of Washington School of Social Work says there are no clear answers about whether stepparents are more likely than birth parents to abuse children. “In studying child abuse, there is a wide range of determinants of risk,” she says, of which the stepparent/child relationship is just one. However, a U.S. Department of Health and Human Services study indicates that of 859,000 child-abuse cases reported in the U.S. in 2007, nearly 80 percent involved “parents of the child,” as opposed to an unmarried partner of the parent or other type of caregiver. And of that figure, only 4.2 percent were stepparents. The generally accepted rationale for stepparent-inflicted abuse, according to Harborview’s Berliner, is that stepparents “have less of a parental investment or bond with the victim.”

In August 2008, Janet was placed in foster care with a family in Lake Forest Park. Her brother soon followed. Messages left for Dwight Thompson, the pair’s foster father, were unreturned.

Late last month, Thompson and other members of the Pomeroy children’s foster family huddled around the kids as they sat in the half-empty courtroom while Jon Pomeroy lobbied King County Judge William Downing for a lenient sentence. Shortly after hearing arguments, the judge summoned Janet—who, Thompson subsequently told the assembled press, had returned to school and grown a full six inches since being removed from the Pomeroy home—to the front of the courtroom to read a letter aloud.

She stopped short of the bench without uttering a word, and quietly returned to the gallery, where she bowed her head and began to cry.

An interview with Janet and Carson’s foster dad, Dwight Thompson, is online here. Thompson and his wife, Irene, of Lake Forest Park, took in the children last year. In the interview, Thompson describes how Janet has been faring since she was removed from the Carnation home and what the family plans to say at the November 6 sentencing hearing for Rebecca Long.