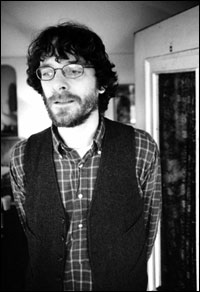

RICHARD BUCKNER

KATHLEEN EDWARDS

Sunset Tavern, 206-784-4880, $12

9 p.m. Fri., Nov. 29

Quick, spot the blurb below that does not appear in Richard Buckner’s bio: “Black is the color of his mood as he expounds on classic themes of betrayal and bottle-drowned hope.” “[He is] not in love with the light but with the loss of it . . . lives in the twilight moment.”

“A brooding Americana singer-songwriter, he’s a restless musical adventurer perpetually seeking new ways to address the darkness.”

OK, so this was a setup. All three apply to Buckner, although the first two are from reviews originally in, respectively, The New York Times and Spin; the third was drafted by yours truly in preparation for this interview. Writers, it seems, tend to approach Buckner expecting to encounter this mopey, uncommunicative, and . . .

“All-around depressed guy?” Buckner laughs heartily at the personal profile I’d imagined. Actually, we’d dispensed with his press image a half hour earlier, kibitzing quite animatedly on everything from his excitement at being a recent Austin transplant to his nigh-obsessive used book- and record-shopping habits while on the road to his thrill in having shared stages with some of his heroes (among them: Peter Case, Townes Van Zandt, and bluegrass legend Doc Watson) during his decade-long tenure as a touring musician.

It’s only when talk turns to international politics—on CNN, Bush has just signed the Iraq war resolution—that his mood turns momentarily sour: “I recently recorded a song for an anti-death penalty compilation put together by Jon Langford [volume two of Executioner’s Last Songs, due next spring on Bloodshot] but otherwise, I’ve never had politics involved with my writing. But—goddamn, this is so disgusting. I think it’s at a point now that I wonder how much longer I’m going to be able to avoid it.”

Buckner’s speaking from a hotel in Manhattan where he’s based for a couple of days, in town to do inaugural showcases for his fifth album, Impasse, his second for hip Chicago indie Overcoat Recordings. Truth be told, while Impasse is nowhere near as daunting and dark in tone as his previous record, 2000’s The Hill (an adaptation of Edgar Lee Masters’ bleak/despairing Spoon River Anthology), the circumstances surrounding it were cloaked in shadow—literally and figuratively.

Impasse was the result, according to Buckner, “of being in a basement in Canada, at a time of year when there wasn’t that much light outside—when it is dark at three in the afternoon—and recording all these dark, weird songs with these weird instruments—never mind all the weirdness that was going on in my life! There’s a certain coldness about the record, at times very unemotional.” Buckner was soon to be headed for a divorce with his wife (and drummer) Penny Jo, so any real-time drama they were going through undoubtedly affected the mood of the sessions.

Too, its making was protracted, to say the least. Going back to the time immediately prior to recording The Hill, Buckner recalls, “I wasn’t exciting myself, the way I was going about writing, and I needed a distraction.” The Hill provided the detour necessary to loosen up his writer’s block— he soon began sketching out Impasse. Buckner initially booked studio time in Portland, recording an album’s worth of material (“a ragged rock record with pedal steel”) there with his longtime producer J.D. Foster and members of Sebadoh. Later, though, when he listened to the tapes, something just didn’t feel right.

“I wasn’t satisfied, and I was at a loss as to why,” recalls Buckner. “I finally figured out it was because I wasn’t working on my own, in my own time, alone—which I really needed to do. So I ended up scrapping the whole session. I bought a digital 24-track, came back to Canada, and rerecorded the whole thing by myself. There are a lot of things on it that are first takes, stuff I got up and recorded in the middle of the night and kept.”

Buckner freely admits that creating the record was a strange experience, but not an unhappy one. “Walking away with it in some ways is like having a souvenir of the time,” he muses, and, in keeping with that notion, he had the booklet lyrics printed as mini-letters and short stories making a continuous narrative, rather than in standard verse/chorus fashion broken up by individual song titles. “I wanted this to be addressing a period of time as a character but also as a period of time, so if I put three sections of the words in letter form and the rest more narrative in dialogue, I thought it might put a little more air in the songs.”

Though relentlessly oblique, the lyrics are fascinating to read as text accompanying the music, whose contrary, oddball arrangements—”Born Into Giving It Up,” for example, with its deceptively upbeat T. Rex boogie-meets-Flaming Lips psych vibe, or “Loaded @ the Wrong Door,” which offsets pissed-offness via Brian Wilson-esque woozy-warm keyboard melody—make Impasse an impressive artistic leap. And Buckner’s voice, it must be said, a part gravelly/part soaring/ perpetually-in-motion instrument, remains one of indiedom’s most distinctive and emotional.

His forthcomingness in picking apart Impasse notwithstanding, Buckner still cautions against equating the art with the artist.

“You know, the real thing I like is when people can put their own experiences into the music and enjoy it that way. What’s going on in my life is so unimportant, it doesn’t matter, because everybody has their lives going on,” he says. “When I listen to certain music that I love, I want to come away with something that’ll affect me. Unless there’s some obvious phrasing going in the lyrics, I really don’t sit there and wonder about the source. I don’t think too much about the artist himself. I just want to take it all in and learn from the music.”