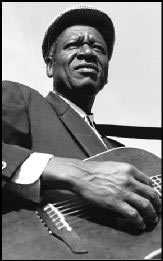

The late, great Fela Kuti never backed down. Even when Nigeria’s government imprisoned him or burned down his house, it didn’t deter the musical firebrand from speaking out on the country’s political and social issues. In the process, Kuti created a powerfully charged style of music called Afrobeat that perfectly mirrored his fiery convictions. Only his untimely death from AIDS in 1997 could stop his voice—and even that, it seems, was a temporary state of affairs. His son, Femi Kuti, has taken up the reins, and the recent welter of Fela archival/reissue material has made him more visible than ever. Add to that 2002’s Red Hot + Riot: The Music and Spirit of Fela Kuti, the newest disc from the AIDS fighting Red Hot Organization—an inspired mix of African and African-American artists, rappers, jazzbos, and beyond, it’s the tribute/ compilation album of the year.

“We’ve been trying to go global and reach out to places where the epidemic is hitting hardest in the world,” explains Paul Heck of Red Hot, the album’s co-producer.

“In the spring of 2000 we were in a session with Amir Thompson (a.k.a ?uestlove of the Roots) for a track off Red Hot + Indigo. The Fela vinyl reissues and box sets had just hit the stores, and he had one. He put on some tracks and said, ‘You should do a Fela tribute and call it Red Hot + Riot.‘ And literally from that, the idea was born. Next day I was on the phone with Femi and Fela’s management, and it went from there.”

Even though it ultimately took two and a half years for the record to appear, there was an immediate synergy about the project. At the time, the Roots’ Thompson was touring with soul singer D’Angelo, “and they were fooling around with Fela’s ‘Water Know No Enemy,'” recalls Heck. “We thought it’d be great to have him do it with Femi, and they recorded it in New York. We didn’t even have a record deal, but we thought it was a way to get things going with a bang.”

Heck insists there was no master plan behind the album’s many inspired collaborations, like the pairing of rapper Common and Malian guitar legend Djelimady Tounkara, who join together for “Years of Tears and Sorrow.” Instead, Heck notes, “We just sat around and thought, ‘Wouldn’t this be great. . .?’ There were no rules. The only way to pay tribute was to bring your own style to what they did. People were great, artists like Djelimady and Chiekh L�me in on short notice. Chiekh had covered “Shankara/Lady” when he was a teenager, which is why he wanted to do it, and he loved what the song was about. His vocal captures Fela’s essence, I think.”

While the album is essentially a series of highlights, the standout moment might well be a scathing version of Fela’s classic “Shuffering and Shmiling,” where socially conscious rappers Dead Prez and Talib Kweli drop knowledge over churning Afrobeat from Femi’s band Positive Force.

“Femi sat with Dead Prez for two hours in the studio talking about organized religion in Nigeria, and why Fela wrote the song,” notes Heck. “They got the message of the song and filtered it through their own sensibilities, and captured the essence of the original. They’re spiritual children of Fela. They’re among the few artists speaking about the same things Fela did. When Stick drops that first line, ‘Religion is like prison,’ and the music cuts out, it still gives me the chills.”

Fela purists might be disturbed by the appearance of two non-Kuti tracks—Kelis’ “So Be It,” and Sade’s “By Your Side.” But ultimately, they fit the album’s feel, and Heck desperately wanted to include a contribution from Sade, Nigeria’s best-known artist.

“I wanted her to do ‘Trouble Sleep’—it’s Fela’s only slow song, like a blues lament, and she does that kind of thing so well. But she doesn’t record tons of stuff, so [she] offered a re-mix of ‘By Your Side,’ with Fela samples instead.”

Despite the varied performers, there’s a remarkable consistency to the music, as the tracks utilizing a core rhythm section, plus classic contributions from jazz stylists Roy Hargrove and Archie Shepp. Still, the record remains a thoroughly forward-looking affair, offering more than a passing nod to electronica.

“There’s a tension between the organic and electronic styles; I wanted the New School stuff in there,” says Heck. “I thought it would be great to have someone doing a turntablist, hip-hop thing with Afrobeat. So I reached out to Mario C., another producer, and he got Mixmaster Mike. And then there’s ‘Kalakouta Show,’ with Blackalicious, which originally was an instrumental; I thought it’d be interesting to hear people rhyme over it.”

Ultimately, Red Hot + Riot is much more than a sum of its big names, whether they’re Nile Rodgers, Baaba Maal, Taj Mahal, or Macy Gray. It truly does evoke the spirit of Fela, both in its political commitment and its musical revolution, successfully mashing forms in a way that hasn’t quite happened before, breaking ground in much the same manner Kuti did when he Cuisinarted funk and highlife. In short, an unqualified success.