Wake up in the morning. You hear the clock ticking. Ticktock. Ticktock. You get ready for work or school. Get dressed, freshen up, eat breakfast, drink coffee. Maybe you don’t do anything at all to prepare. But the clock still ticks. Ticktock. Ticktock. You look at the clock. I’m late. Ticktock. Ticktock. You rush to beat the clock. But it will always win. We are all living around a clock that one day will stop ticking. You might think that the day has just begun, but it’s just another second, another minute, another hour, another day closer to your death.

You are dying. Right. Now.

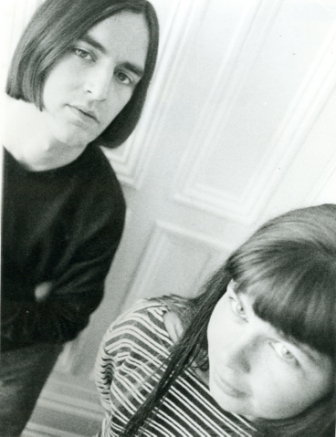

“Grim Reaper Blues,” the first track off Entrance’s latest recording, Prayer of Death, sounds morbid (“That old Grim Reaper, baby/He’s a friend of mine/24 years old and I don’t mind dying”), but it serves as the portal into the mind of its writer, 25-year-old L.A.-based musician Guy Blakeslee, who has been traveling under the moniker Entrance for five years. “Grim Reaper Blues” is a swaggering acid-blues burner drenched in reverb, pounding drums, and Blakeslee inviting the ominous Reaper inside, willing to accept the fate he brings forth.

On the surface, death seems to be the theme of Prayer of Death, but underlying all the shamanistic, personal sacrifice, Blakeslee says there are still so many ways to interpret the album.

“It has to do with the convex of personal life. The larger world is in violence or potential violence—that’s what makes the shock wave of death and war very strong,” says Blakeslee. “We have a lot of responsibility as to how much we scare ourselves. You’re the one that is in charge of your experience.”

Fear is part of the current American psyche. The events that unfolded on Sept. 11 created and ingrained a deeper fear in all Americans, including Blakeslee, who was in Canada with the Baltimore-based band the Convocation Of, for which he played bass, when tragedy struck. Blakeslee promptly quit midtour and decided to go off on his own.

“I felt like the world would end. I was pretty unhappy doing what I was doing. It seemed like there wasn’t a lot of time left,” he says. “I wanted to go towards music that reflects how I feel about the world. I wanted to be a leader.”

Blakeslee, who was already writing solo material when he quit the band, quickly began working on the songs that would surface on Entrance’s 2003 debut album, The Kingdom of Heaven Must Be Taken by Storm. Free of restraint from band members, Blakeslee created a rich, bluesy acoustic folk album that would inadvertently peg him as that “young, white Delta blues guy.”

“That’s basically what I was trying to avoid, but it happened anyway,” he says.

Of course, it wasn’t entirely a bad thing. After Tiger Style, the label that released The Kingdom of Heaven and follow-up EP Honey Moan, went under, the “young, white Delta blues guy” inked a deal with Mississippi blues label Fat Possum, which released his second LP, Wandering Stranger, in 2004. But that relationship turned sour not long after it blossomed. Though Wandering Stranger and Prayer of Death were recorded when Blakeslee was without a label, it was something Blakeslee says benefited him because it “enabled me to do what I wanted to do.” Prayer of Death was initially released on his own Entrance Records imprint last year before Tee Pee Records picked it up and rereleased it this past fall to wide acclaim. What sets Prayer of Death apart from his past recordings is that it was done with a full band. And it’s more than just a blues album—it’s a modern psychedelic masterpiece, woven with an instrumental sitar eulogy (“Requiem for Sandy Bull”), powerful string arrangements, and daring travels into an alternate rock and roll universe.

More than anything, Prayer of Death is about finding inner peace with oneself, something Blakeslee bestows on the final track, “Never Be Afraid.” Blakeslee was influenced by Bardo Thodol, better known as the Tibetan Book of the Dead, which describes the experiences of the consciousness between death and rebirth.

“The accumulation of what you’ve done is not contributing to what’s going to happen in the future,” says Blakeslee. “That’s what the world is—full of cycles and patterns. Nothing starts and nothing ends.”

You wake up in the morning. You hear the clock ticking. Ticktock. Ticktock.